Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the following friends, colleagues, and mentors for their encouragement, support, and Guidance.

Dr. M. Eugene Tardy, Jr., has been an inspirational mentor and friend, whose advice and encouragement were instrumental in this project’s development.

Our mentors in Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery and in Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery are a continuing source of inspiration and guidance.

Department Chairmen, Ed Applebaum at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and David Kennedy at the University of Pennsylvania deserve special thanks for supporting and facilitating this undertaking.

Devin M. Cunning deserves much appreciation. His medical illustrations speak for themselves, but do not tell of the countless hours of collaboration, hard work, and multiple revisions.

Danette Knopp of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins provided publishing leadership from the very conception of the project to its completion.

Sara Lauber of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins played an instrumental role in guiding the manuscript through its final, critical stage.

Patrick Carr deserves thanks for his outstanding work as Production Editor.

Dean M. Toriami, M.D. Daniel G. Becker, M.D.

Preface

The successful rhinoplasty surgeon’s operative plan is based on a clear understanding of the patient’s desired changes, a careful and accurate diagnosis of the patient’s anatomy, and a wide armamentarium of surgical techniques. Prior techniques and the surgeon’s personal experiences with the array of surgical techniques are also primary factors in the decision for a particular operative approach. The successful surgeon’s application of surgical techniques is designed to accommodate differences in anatomy and to account for variant anatomy. For example, noses with thin skin and noses with thick skin each present specific problems that must be considered when choosing techniques for altering nasal structure. Also, the effects of scar contracture vary from patient to patient and can significantly affect the ultimate aesthetic and functional outcome. The rhinoplasty surgeon must recognize that the healing process may distort the changes made at the time of surgery, however expertly they were accomplished. The surgeon’s only recourse is to build a structurally sound nasal architecture that can withstand the forces of scar contracture and provide an acceptable success rate.

The importance of experience in rhinoplasty cannot be overemphasized. The experienced rhinoplasty surgeon can anticipate the likelihood of a favorable outcome based on his or her experience using certain techniques with a specific deformity. Selection of the proper technique for each circumstance should provide the opportunity for a high success rate.

The purpose of this dissection manual is to provide practical information about a wide range of surgical techniques in rhinoplasty. The dissection manual guides the reader through a step-by-step dissection. It focuses on the execution of basic and advanced rhinoplasty techniques and seeks to provide practical information that can be readily applied in surgery. The text is intended to be a procedurally oriented dissection manual and is organized to allow easy reference to a wide array of basic and advanced rhinoplasty techniques. Illustrations and intraoperative photographs, along with detailed text, guide the reader through the step-by-step dissection. Important technical and clinical “pearls” are high- lighted in each section. A programmatic cadaver dissection videotape accompanies the text.

Before beginning the nasal dissection, review the chapter on nasal anatomy (Chapter 1) and the chapter on pre-operative rhinoplasty analysis (Chapter 2). Chapter 3 outlines local anesthesia injection techniques, the dissector is instructed to practice the injections prior to commencing the programmatic dissection.

The dissection manual guides you through the following dissections: septoplasty, transcartilaginous or inter-cartilaginous approach, delivery approach and an external rhinoplasty approach. The remainder of the programmatic nasal dissection details a number of rhinoplasty techniques and addresses a number of specific rhinoplasty problems. The manual focuses primarily on the external rhinoplasty approach; however, all approaches are covered and can be performed sequentially, or the dissector may choose to focus on a specific approach. Appropriate targeted references for further reading are also provided.

We recommend that the dissector proceed with Chapters 1-6 with the skin-soft tissue envelope intact. For the remaining chapters, the dissector may wish to split the skin down the midline for better exposure. In this fashion, the dissection can be performed without an assistant, and (except for a complete septoplasty) without it headlight.

The cadaver laboratory is the place to sharpen one’s surgical skills. This manual seeks to provide the dissector with the opportunity to obtain maximum benefit from performing this complex operation on cadaver specimens. The dissection manual was “field-tested” at the University of Pennsylvania Rhinoplasty Course : Aesthetic & Functional Rhinoplasty. Participants, many of whom professed relatively limited rhinoplasty experience, undertook the stepwise, programmatic dissection and worked through the manual (with the exception of riborclavarial bone harvest) in a single five-hour period.

Rhinoplasty is an operation that requires constant thought, assimilation of information, and reaction to unexpected findings. With this in mind, the authors strongly recommend involvement in as many advanced teaching encounters as possible. This may involve reading timely literature, attending advanced rhinoplasty courses. observing other experienced surgeons, or sharpening one’s skills in the cadaver laboratory. We hope that use of this dissection manual will stimulate thought and incite both the enthusiasm of the beginner as well as experienced rhinoplasty surgeons seeking to broaden their surgical armamentarium.

Dean M. Toriumi, M.D. Daniel G. Becker, M.D.

Chapters

Foreward

Excellent surgical outcomes in rhinoplasty derive from two interrelated factors: (1) a detailed understanding of the multiple nasal anatomic variants encountered, and (2) an acquired knowledge of the ultimate long-term effects of surgical alterations of these anatomic components—the evolution of healing.

The first skill can be learned by detailed observation, enhanced by cadaver dissection, the second skill only by careful follow-up of operated patients over time.

The general concepts of nasal anatomy have been fundamentally clear for centuries, but only in recent decades have surgeons appreciated the finely detailed nuances of nasal anatomic dynamics that influence the surgical creation of a natural, pleasing rhinoplasty result, free of surgical stigmata. A detailed comprehension of nasal anatomy must therefore transcend knowledge of basic anatomic relationships. The surgeon must judge, by inspection and palpation, the character of the skin and subcutaneous tissues as they vary from nasal region to region, the influences of facial mimetic musculature, the relative strength and support of the cartilaginous and bony framework and substructure, and the limitations imposed by the interrelationship of all these structures upon the ultimate favorable result. As important as the evaluation of what can reasonably be accomplished during rhinoplasty is the acquired knowledge and skill to assess what cannot be accomplished.

This judgment is largely predicated on the critical analysis of each patient’s individual anatomy, coupled with technical refinements guided by experience, and generally requires years of personal surgical result evaluation to become keen.

In this dissection manual, Drs. Becker and Toriumi have created a unique study guide and cadaver dissection manual dedicated to guiding the learner in a disciplined manner. They admirably extend the tradition of the University of Illinois Department of Otolaryngology’s leadership in teaching anatomy and surgery in rhinoplasty. Cadaver dissection constitutes a privilege not available to all, and, as such, this precious material must be wisely and conservatively approached. Experience teaches that a disciplined, structured approach to dissection of the nose produces the best educational outcome.

An important favorable development in contemporary rhinoplasty is the appropriate concern for conservative and subtle anatomic changes that by definition derives from a preservative attitude toward nasal tissues. Commonly, rather than excisional sacrifice of large segments of cartilage or bone, a philosophy of preservation and restoration of tissues is developing that precludes creation of unnecessary tissue voids which may heal and scar unpredictably. Wise surgeons recognize that even a larger nose, well balanced to the surrounding facial features, is always aesthetically preferable to a nose made over-small by radical surgery. Conservation surgery thereby further extends the surgeon’s control over the final surgical result, as an appropriate equilibrium between the corrected nasal skeleton and soft tissue covering is more reliably achieved. Conservative sculpture and volume reduction of the alar cartilages clearly produce more favorable results, generally avoiding major resections and vertical interruption of the intact residual strip of lateral and medial crus. Notching, pinching, afar cephalic retraction, over-rotation, and asymmetries are all almost entirely eliminated in long-term healing when this conservative philosophy is embraced. A further striking example of conservatism is the preservation of a strong, high pro-file in many patients, a distinct contrast to the dramatic retrousee profiles created in decades past by sacrifice of over-generous segments of nasal bony humps.

Finally, thoughtful nasal surgeons, through accurate anatomic diagnosis, discern which portions of the nasal anatomy are pleasing and satisfactory, striving to avoid disturbing these structures and areas when correcting (or gaining access to) anatomic components in need of correction. This philosophy further extends the surgeon’s favorable control over ultimate healing. Thoughtful cadaver dissection provides the learner with visual pathways to gain access to structures to be modified, while preserving normal tissues and relationships. Important tissue planes, vital in live surgery, can be appreciated best when viewed at leisure in the dissection laboratory.

This well-conceived work, properly employed, contributes substantially to shortening the steep learning curve characteristic of rhinoplasty.

M. Eugene Tard ‘ v, Jr., M.D., F.A.C.S.

Professor of Clinical Otolaryngology Director, Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery University of Illinois Medical Center Chicago , Illinois

Professor of Clinical Otolaryngology Indiana University School of Medicine

Appendix A – Tripod Concept

TRIPOD CONCEPT

When considering the effect of surgical techniques on the nose, one may think of the tip as a tripod, with each lateral crus composing one leg of the tripod, and the paired medial crura composing the third leg (1,2). Shortening the two ” lateral crural” legs will cause the tripod to fall in that direction, thereby ” rotating and deprojecting” the tripod. Weakening these two legs (as with cephalic resection) is also said to have the same effect (although less so), as the healing forces applied to these weakened legs of the tripod will cause the tip to rotate and deproject slightly over time. Similarly, a columellar strut will strengthen the ‘ °medial crural” leg of the tripod. Use of a columellar strut to correct buckled medial or intermediate crura may increase tip projection and rotation. Even though the tripod concept oversimplifies the dynamics of the nasal tip, it provides those with little experience in rhinoplasty with a method of predicting the effects of specific techniques.

REFERENCES

- Anderson JR. A reasoned approach to nasal base surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1984;110: 349-358.

- McCollough EG. Surgery of the nasal tip. Otolaryngol Clin North Ain 1987;20:769-784.

Appendix B – Guide to Nasal Analysis

NASAL ANALYSIS

General

Skin quality: Thin, medium, or thick

Primary descriptor (i.e., why is the patient here): For example, big, twisted,1M large hump

Frontal View

Twisted or straight: Follow brow-tip aesthetic lines Width: Narrow, wide, normal, wide-narrow-wide Tip: Deviated, bulbous, asymmetric, amorphous, other

Base View

Triangularity: Good versus trapezoidal

Tip: Deviated, wide, bulbous, bifid, asymmetric

Base: Wide, narrow, or normal. Inspect for caudal septal deflection

Columella: Columellar/lobule ratio (normal is 2:1 ratio); status of medial crural footplates.

Lateral View

Nasofrontal angle: Shallow or deep

Nasal starting point: High or low

Dorsum: Straight, concavity, or convexity; bony, bony-cartilaginous, or cartilaginous (i.e., is convexity primarily bony, cartilaginous, or both)

Nasal length: Normal , short, long

Tip projection: Normal , decreased, or increased

Alar-columellar relationship: Normal or abnormal

Naso-labial angle: Obtuse or acute

Oblique View

Does it add anything, or does it confirm the other views?

Many other points of analysis can be made on each view, but these are some of the vital points of commentary.

Appendix C – Aesthetic Analysis

LANDMARKS FOR ANALYSIS: POINTS

See figures on page 10.

Trichion: Anterior hairline in the midline

Glabella: Most prominent midline point of forehead, well appreciated on lateral view Nasion: Most posterior midline point of forehead, typically corresponds to nasofrontal suture

Rhinion: Soft-tissue correlate of osseocartilaginous junction of nasal dorsum Sellion: Osseocartilaginous junction of nasal dorsum

Supratip: Point cephalic to the tip

Tip: Ideally, most anteriorly projected aspect of the nose

Subnasale: Junction of columella and upper lip

Labrale superius: Border of upper lip

Stomion: Central portion of interlabial gap

Stomion superius: Lowest point of upper-lip vermilion

Stomion inferius: Highest point of lower-lip vermilion

Mentolabial sulcus: Most posterior midline point between lower lip and chin Pogonion: Most anterior midline soft-tissue point of chin

Menton: Most inferior point on chin

Cervical point: Point of intersection between line tangent to neck and line tangent to sub-mental region

Gnathion: Point of intersection between line from subnasale to pogonion and line from cervical point to menton

Appendix D – Surface Angles, Planes, and Measurements

Measurements: Definitions

Facial thirds

Upper third: Trichion to glabella

Middle third: Glabella to subnasale

Lower third: Subnasale to menton

Horizontal fifths: Five equally divided vertical segments of the face

Frankfort plane: Plane defined by a line from the most superior point of auditory canal to most inferior point of infraorbital rim

Nasofrontal angle: Angle defined by glabella-to-nasion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal, 115 to 130 degrees (within this range, more-obtuse angle more favorable in female, and more acute angle in male patients)

Nasofacial angle: Angle defined by glabella-to-pogonion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal, 30 to 40 degrees

Nasomental angle: Angle defined by nasion-to-tip line intersecting with tip-to-pogonion line. Normal, 120 to 132 degrees

Relationship of lips

To nasomental line: Upper lip, 4 mm behind; lower lip, 2 mm behind line from nasal tip to menton

To subnasale-to-pogonion line: Upper lip, 3.5 mm anterior; lower lip, 2.2 mm anterior Mentocervical angle: Angle defined by glabella-to-pogonion line intersecting with menton-to-cervical point line

Legan facial-convexity angle: Angle defined by glabella-to-subnasale line intersecting with subnasale-to-pogonion line; normal, 8 to 16 degrees

PEARL

Useful in assessing chin deficiency, candidacy for chin implant, chin advancement, or other chin alteration

Nasolabial angle: Angle defined by columellar point-to-subnasale line intersecting with subnasale-to-labrale superius line; normal, 90 to 120 degrees (within this range, more obtuse angle more favorable in female, and more acute in male patients)

Columellar show: Alar-columellar relationship as noted on profile view; 2 to 4 mm of columellar show is normal

Nasal projection: Anterior protrusion of nasal tip from face

Goode’s method: A line drawn through the alar crease, perpendicular to the Frankfurt plane. The length of a horizontal line drawn from the nasal tip to the alar line divided by the length of the nasion-to-nasal tip line. Normal, 0.55 to 0.60 (2,3)

Crumley’s method: The nose with normal projection forms a 3-4-5 triangle (i.e., alar point-to-nasal tip line (3), alar point-to-nasion line (4), nasion-to-nasal tip line (5) (4). Byrd’s method: Tip projection is two-thirds (0.67) the planned postoperative (or the ideal) nasal length. Ideal nasal length in this approach is two-thirds (0.67) the midfacial height (5)

Powell and Humphries Aesthetic Triangle

Nasofrontal: 115 to 130 degrees

Nasofacial: 30 to 40 degrees

Nasomental: 120 to 132 degrees Mentocervical: 80 to 95 degrees

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME, Walter MA, Patt BS. The overprojecting nose: anatomic component analysis and repair. Facial Plast Surg 1993;9:306-316.

- Ridley MB . Aesthetic facial proportions. In: Papel ID, Nachlas NE , eds. Facial plastic and reconst r uctive surgery. St. Louis : Mosby Year Book, 1992:99-109.

- Crumley RL, Lamer M. Quantitative analysis of nasal tip projection. Laryngoscope 1998;98:202-208.

- Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plast Recon.str Surg 1993;91: 642-654.

Appendix E – Tip Support, Incisions, and Approaches

MAJOR TIP-SUPPORT MECHANISMS

Size, shape, and strength of lower lateral cartilages

Medial crural footplate attachment to caudal septum

Attachment of caudal border of upper lateral cartilages to cephalic border of lower lateral cartilages

[Nasal septum also is considered a major support mechanism of the nose.[ MINOR TIP-SUPPORT MECHANISMS

Ligamentous sling spanning the domes of the lower lateral cartilages (i.e., interdomal ligament)

Cartilaginous dorsal septum

Sesamoid complex of lower lateral cartilages

Attachment of lower lateral cartilages to overlying skin/soft-tissue envelope

Nasal spine

Membranous septum

INCISIONS: METHODS OF GAINING ACCESS

Intercartilaginous

Transcartilaginous

Marginal (NOT to be confused with rim incision)

Transcolumellar

APPROACHES: PROVIDE SURGICAL EXPOSURE

Cartilage-splitting

Retrograde

Delivery: Marginal + intercartilaginous incision

External approach: Marginal + transcolumellar incision

SCULPTING TECHNIQUES: SURGICAL MODIFICATIONS

Complete strip (i.e., cephalic resection) or volume reduction of lateral crura

Incomplete strip (dome division)

Transdomal/domal sutures

Augmentation grafting

Tip graft

Other

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME. R/tinoplasly: the art and the science. Philadelphia : WB Saunders, 1997.

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Philosophy and principles of rhinoplasty. In: Cummings C.W. Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, et al., eds. Otolaryngology: head & neck surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis : Mosby Year Book. 1993: 278-294.

Appendix F – Achieving Surgical Goals: Selected Options

INCREASE ROTATION

Lateral crural steal

Transdomal suture that recruits lateral crura medially

Base-up resection of caudal septum (variable effect)

Cephalic resection (variable effect) Lateral crural overlay

Columellar strut (variable effect) Plumping grafts (variable effect)

Illusions of rotation: increased double break, plumping grafts (blunting nasolabial angle)

DECREASE ROTATION (COUNTERROTATE)

Full transfixion incision Double-layer tip graft Shorten medial crura Caudal extension graft Reconstruct L-strut, as in rib graft reconstruction (integrated dorsal graft/columellar structure of saddle nose)

INCREASE PROJECTION

Lateral crural steal increased projection, increased rotation

Tip graft

Plumping grafts

Premaxillary graft

Septocolumellar sutures (buried) Columellar strut (variable effect) Caudal extension graft

DECREASE PROJECTION

High partial, or full transfixion incision

Lateral crural overlay (decreased projection, increased rotation)

Nasal spine reduction

Vertical dome division with excision of excess medial crura, with suture reattachment

INCREASE LENGTH

Caudal extension graft Radix graft

Double-layer tip graft Reconstruct L-strut

DECREASE LENGTH

See increase rotation

Also, deepen nasofrontal angle

Set-back and suture medial crura to midline caudal septum

TIP REFINEMENT

Cephalic resection (volume reduction)

Dome-binding sutures

Vertical dome division, with suture reconstitution Tip graft

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: the art and the science. Philadelphia : WB Saunders, 1997.

- Johnson CM Jr, Toriumi DM. Open structure rhinoplasty. Philadelphia : WB Saunders, 1990.

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Philosophy and principles of rhinoplasty. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM,

- Harker LA, et al., eds. Otolaryngology: head & neck surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis : Mosby Year Book, 1993: 278-294

Appendix G – Selected Complications of Rhinoplasty

Bossae: A knuckling of lower lateral cartilage at the nasal tip caused by contractural healing forces acting on weakened cartilages. Patients with thin skin, strong cartilages, and nasal-tip bifidity are especially at risk. Excessive resection of lateral crux and failure to eliminate excessive interdomal width may play some role in bossae formation.

Polly beak: Postoperative fullness of the supratip, with an abnormal tip-supratip relation. This has several etiologies: Failure to maintain adequate tip support (postoperative loss of tip projection), inadequate cartilaginous hump (anterior septal angle) removal, and/or supratip dead space/scar formation.

Treaent depends on anatomic cause. If the cartilaginous hump was underresected, then resect additional dorsal septum. One also must ensure adequate tip support. Ma neuvers such as placement of a columellar strut may be of benefit. If the bony hump was overresected, consider a graft to augment the bony dorsum. If a polly-beak is from excessive scar formation, consider triamcinolone (Kenalog) injection or skin taping in the early postoperative period, before any consideration of surgical revision.

Inverted V deformity: Inadequate support of the upper lateral cartilages after dorsal-hump removal can lead to inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages and an inverted V deformity. In this deformity, the caudal edges of the nasal bones are visible in broad relief. Inadequate infracture of the nasal bones is also a frequent cause. When executing hump excision, it is helpful to preserve the underlying nasal mucoperichondrium (extramucosal dissection), which provides significant support to the upper lateral cartilages and helps decrease the risk of inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages after hump excision. When undertaking osteotomies after hump excision, appropriate infracture and narrowing of the bony vault must be achieved.

Rocker deformity: If osteotomies are taken too high, into the thick frontal bone, the supe rior aspect of the osteotomized nasal bone may project or rock laterally when the bone is infractured. This is a rocker deformity. A 2-mm osteotome may be used percutaneously to create a more appropriate superior fracture line and correct the rocker deformity.

Dorsal irregularities: After creation of an open roof by hump removal, the bony mar-gins should be smoothed with a rasp. Any bony fragments should be removed, making sure that all obvious particles are removed from under the skin/soft-tissue envelope. Fail ure to remove all fragments may lead to a visible and/or palpable dorsal irregularity.

Nasal valve collapse: The surgeon should recognize the existence of the internal and external nasal valve. The internal nasal valve area is bounded by the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage, septum, and floor of the nose. The external nasal valve refers to the area delineated by the cutaneous and skeletal support of the mobile alar wall. Exces sive narrowness in either of these locations may cause nasal obstruction. Weakness at ei ther of these locations may result in collapse with the negative pressure of inspiration, resulting in nasal airway obstruction. Nasal valve collapse is seen most often as a sequela of overresection of lateral crura or middle vault collapse. Overaggressive resection of the lateral crura and the subsequent postoperative soft-tissue contraction frequently leads to nasal valve compromise.

REFERENCES

- Simons RL, Gallo IF. Rhinoplasty complications. Facial Plast Surg Clirr North Am 1994:2:521-529.

- Kamer FM, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, ed. Head and Neck Surgery Otolaryngology. Philadelphia : Lippincott, 1998:2663-2676.

- Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger RY, Key M. The cartilaginous pollybeak: etiology, prevention, and treaent. Facial Plast Surg 1989:6:113-120.

- Larrabee WF Jr. Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Mast Surg C/in North Am 1993;1: 23-38.

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault. Opel- Tech Plast Recoostr Surg 1995;2:16-30.

- Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME. Powered instrumentation for dorsal nasal reduction. Facial Plast Surg 1997;13:291-297.

Appendix H – Adjunctive Procedures

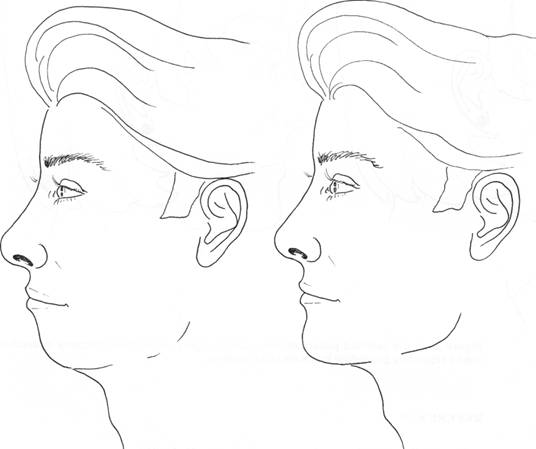

Figure 1. Chin augmentation can be a useful adjunctive procedure to create facial balance in the patient with an underdeveloped chin. In this illustration, only the chin differs between these two line drawings.

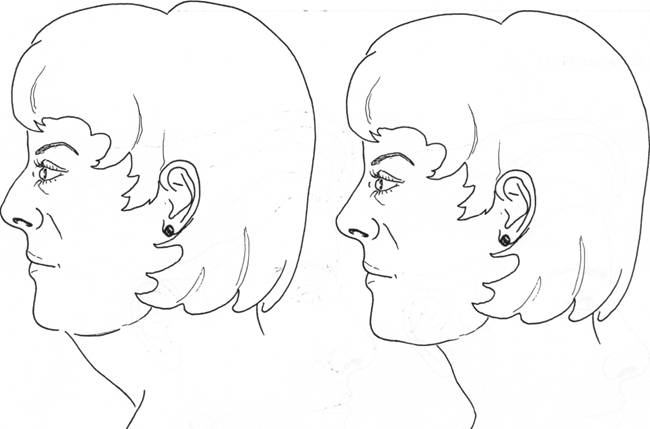

Figure 2. In the selected patient seeking nasal surgery, submental lipectomy is another useful adjunctive procedure to create facial balance.

REFERENCE

- Tardy ME, Thomas JR. Facial aesthetic surgery. Philadelphia : Mosby, 1995.

Appendix I – Cleft Lip Nasal Deformity

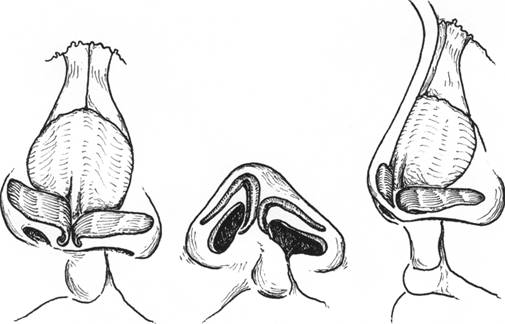

UNILATERAL CLEFT (Fig. 3)

Nasal tip:

Medial crus of LLC shorter on cleft side

Lateral crus of LLC longer on cleft side (total length of cleft and noncleft side LLC are the same)

Tip-defining point on cleft side is flat and laterally displaced

Columella:

Short on cleft side

Columellar base directed to noncleft side (unopposed orbicularis muscle)

Nostril:

Horizontal orientation on cleft side

Alar base:

Laterally, inferiorly, and posteriorly displaced on cleft side

Nasal floor:

Usually absent

Septum:

Caudal deflection to noncleft side

Posterior deflection to cleft side

BILATERAL CLEFT

Figure 3. Cleft-lip nasal deformity. Typical anatomic findings characteristic of unilateral cleft-lip nasal deformities.

Nasal tip:

Medial crura short bilaterally

Lateral crura short bilaterally, caudally displaced Tip-defining points poorly defined and widely separated Columella:

Short, with a wide base

Nostrils:

Horizontal orientation bilaterally

Alar base:

Laterally, inferiorly, and posteriorly displaced bilaterally Nasal floor:

Usually absent bilaterally

REFERENCE

- Sykes JM, Senders CW. Wang TD, Cook TA. Use of the open approach for repair of secondary cleft lip nasal deformity. Facial Plasi Surg Clin North Am 1993; I : I I 1-126.

Appendix J – Photography Setup (1)

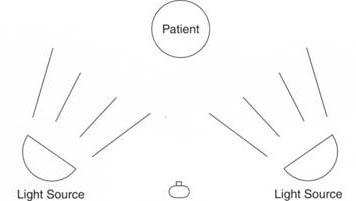

(Fig. A-4)

Camera: 35-mm SLR (single light reflex camera) with I05-mm macro lens

Lighting: dual electronic flash units; overhead kicker light adds a backlighting effect that improves picture quality and softens or eliminates background shadows

Background: Nassau blue no. 25 Film: Kodak Ektachrome ASA 100 STANDARD RHINOPLASTY VIEWS

1:7, frontal, base, lateral, oblique 1:5 and 1:3, close-up, base view

REFERENCE

- Tardy ME, Brown R. Principles of photography in facial plastic surgery. New York : Thieme Publishers, 1992

Appendix K – Indications For External Rhinoplasty Approach

Asymmetric nasal tip

Crooked-nose deformity (lower two thirds of nose)

Saddle-nose deformity Cleft-lip nasal deformity

Secondary rhinoplasty requiring complex structural grafting

Septal-perforation repair

REFERENCES

- Johnson CM Jr, Toriumi DM. Open structure rhinoplasty. Philadelphia : W B Saunders. 1990.

- Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Open structure rhinoplasty: featured technical points and long-term lolloss-up. Fa‑cial Plast .Surer; Clin North Am 1993;

Appendix L – Suggested Surgical Instruments for Rhinoplasty

1. Needle holder

2. Bayonet forceps

3. Mallet

4. Takahashi forceps

5. Siegel retractor

6. Converse retractor

7. Hemostat (curved)

8. Hemostat (straight)

9. Small nasal speculum

10. Large nasal speculum 1

I. Small single skin hook

12. Small double skin hook

13. Small double skin hook

14. Medium double skin hook

15. Wide double skin hook

16. Freer/Cottle elevator

17. Joseph elevator

18. Converse scissors

19. Fomon scissors

20. Straight Stevens scissors

21. Curved Stevens scissors

22. Curved Iris scissors

23. Scalpel handle

24. Scalpel handle

25. Brown-Adson forceps

26. Brown-Adson forceps

27. Bishop-Harmon forceps

28. Bishop-Harmon forceps

29. 2.0-mm unguarded osteotome

30. 3.0-mm straight unguarded osteotome

31. 3.0-mm straight guarded osteotome

32. 2.5-mm straight guarded osteotome

33. Medical grade sharpening stone

34. Dorsal (Rubin) osteotomes: small, medium, large

35. Rasps with tungsten-carbide inserts: 1/2, 3/4, 5/6

36. Aiache cartilage crusher

37. No. 10 Frazier tip suction

Appendix M – List of Selected Companies with Address/Phone Numbers

RHINOPLASTY INSTRUMENT SETS

Anthony Products, Inc., Indianapolis , IN 800 428-1610

Ellis Instruments, Inc., Madison , NJ 800 218-9082

Instruments Unlimited, Quakertown , PA 800 818-0094

Invotec, Jacksonville , FL 800 998-8580

Lorenz Surgical, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-7711

MicroFrance, St. Aubin , France 800-874-5797

Smith-Nephew-Richards, Madison , WI 888 395-8060

Snowden Pencer, Tucker, GA 800 843-8600

Storz Instruments, St. Louis , MO 800 325-9500

Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-5797

ALLOPLASTIC CHIN IMPLANTS

Allied Biomedical, Paso Robles, CA 800 276-1322

Hanson Medical, Inc., Kingston , WA 800 771-2215

Invotec, Jacksonville , FL 800 998-8580

Porex Surgical, Inc., College Park , GA 800 521-8145

W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff , AZ 800 528-8763

Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-5797

ALLODERM

LifeCell Corporation, The Woodlands, TX 800 367-5737

DERMABOND (OCTYL-2-CYANOACRYLATE)

Ethicon, Somerville , NJ 800 888-9234

RHINOPLASTY POWER INSTRUMENTATION

Linvatec/Hall Surgical Products Group, Largo, FL 800 925-4255

United American Medical, McMinnville , TN 800 521-5002

Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-5797

NASAL SPLINTS

Invotec, Jacksonville , FL 800 998-8.580

Shippert Medical Technologies ( Denver Splints), Englewood , CO 800 888-8663

Vision Medical (Thermoplast), Peoria , AZ 800 874-5797

Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-5797

INTRANASAL PACKS

Invotec, Jacksonville , FL 800 998-8580

Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville , FL 800 874-5797

Appendix N – Selected Recommended Literature

Adamson PA. Open rhinoplasty. In: Papel ID, Nachlas NE , eds. Facial plastic & reconstructive surgery. St. Louis : Mosby Year Book, 1992:295-304.

Anderson JR. A reasoned approach to nasal base surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1984;110:349-358. Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME. Powered instrumentation for dorsal nasal reduction. Facial Plast Surg 1997;13:291-297.

Becker DG, Weinberger MS, Greene BA, Tardy ME. Clinical study of alar anatomy and surgery of the alar base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:789-795.

Beeson WH. The nasal septum. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20:743-767.

Byrd HS, Andochick S, Copit S, Walton KG. Septal extension grafts: a method of controlling tip projection shape. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;100:999-1010.

Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plast Reconstr Surg I993;91:642-654, discussion 655-656.

Cheney ML, Glicklich RE. The use of calvarial hone in nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121:643-648.

Constantian MB. The incompetent external nasal valve: pathophysiology and treaent in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;93:919-933.

Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway ob ;struction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:38-54.

Crumley RL, Lanser M. Quantitative analysis of nasal tip projection. Laryngoscope 1998;98:202-208.

Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty and rib grafts: evolving a flexible operative technique. Plast Reconst r Surg 1992;94: 597-611.

Farrior RT. The osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 1978;88:1449.

Goode RL. Surgery of the incompetent nasal valve. Laryngoscope 1985:95:546-555.

Gunter JP. The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99:863-867.

Gunter JP, Clark CP, Friedman RM. Internal stabilization of autogenous rib cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty: a bar;rier to cartilage warping. Plus’ Reconstr Surg 1998;100:161-169.

Gunter JP, Clark CP, Friedman RM. Internal stabilization of autogenous rib cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty: a bar;rier to cartilage warping. Plctst Reconstr Surg 1997;100:161-169.

Gunter JP, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Re;constr Surg 1997;99:943-955.

Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Management of the deviated nose: the importance of septal reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg 1988;15:43-55.

Gunter JP, Rohrich RI . Augmentation rhinoplasty: dorsal onlay grafting using shaped autogenous septal cartilage. Plant Reconstr Surg 1990;86:39-45.

Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Friedman RM. Classification and correction of alar-columellar discrepancies in rhino;plasty. Plus’ Reconstr Surg 1996;97:643-648.

Johnson CM Jr, Godin MS. The tension nose: open structure rhinoplasty approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;95: 43-51.

Johnson CM Jr, Godin MS. The tension nose [Letter, comment]. Plant Reconstr Surg 1996;97:246. Johnson CM Jr, Toriumi DM. Open structure rhinoplasty. Philadelphia : WB Saunders, 1990.

Kamer FM, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, ed. Head and neck surgery otolaryngology. Philadel;phia : Lippincott, 1998:2663-2676.

Kasperbauer JL, Facer GW, Kern EB. Reconstructive surgery of the nasal septum In: Papal ID, Nachlas NE , eds.

Facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia : Mosby Year Book, 1992:337-343.

Konior RJ, Kridel RWH. Controlled nasal tip positioning via the open rhinoplasty approach. Facial Plant Clin

North Ana 1993;1:53-62.

Kridel RWH, Konior RJ. Controlled nasal tip rotation via the lateral crural overlay technique. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:411-415.

Larrabee WF Jr, Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Plast Sing Clin North Am 1993;1:23-38. Metzinger SE, Boyce RG, Rigby PL, Joseph JJ, Anderson JR. Ethmoid bone sandwich grafting for caudal septa] defects. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1994; I20: 1121-1 125.

McCollough EG. Surgery of the nasal tip. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20:769-784.

McCollough EG, Mangat D. Systematic approach to correction of the nasal tip in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 1981:107:12-16.

Murakami CS, Cook TA, Guida RA. Nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Oto;laryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:327-330.

Murakami CS, Larrabee WF. Comparison of osteotomy techniques in the treaent of nasal fractures. Facial Plast Surg 1992;8:209-219.

Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH. Rhinoplasty with advancing age: characteristics and management. Clin Plast Surg 1996; 23:281-296.

Schwartz MS, Tardy ME. Standardized photodocumentation in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg 1990;7: 1-12.

Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73:230-237.

Sheen JH. Tip graft: a 20 year retrospective. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;91:48-63.

Simons RL. Vertical dome division in rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987:20:785-796. Simons RL, Gallo JF. Rhinoplasty complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;2:521-529.

Sykes JM, Senders CW, Wang TD, Cook TA. Use of the open approach for repair of secondary cleft lip nasal de‑ formity. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:111-126.

Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty in midlife. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1980;13:289-303.

Tardy ME. Ethics and integrity in facial plastic surgery: imperatives for the 21st century. Facial Plast Surg 1995; 11:111-115.

Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: the art and the science. Philadelphia : WB Saunders, 1997.

Tardy ME, Becker DG, Weinberger MS. Illusions in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 1995;11:117-138.

Tardy ME, Broadway D. Graphic record-keeping in rhinoplasty: a valuable self-learning device. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6:108-112.

Tardy ME, Brown R. Surgical anatomy of the nose. New York : Raven Press, 1990.

Tardy ME, Brown R. Principles of photography in facial plastic surgery. New York : Thieme Publishers, 1992. Tardy ME, Cheng E. Transdomal suture refinement of the nasal tip. Facial Plast Surg 1987;4:317-326.

Tardy ME, Cheng EY, Jernstrom V. Misadventures in nasal tip surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20: 797-823.

Tardy ME, Denneny J, Fritsch MH. The versatile cartilage autograft in reconstruction of the nose and face. Laryn; goscope 1985;95:523-532.

Tardy ME, Genack SH, Murrell GL. Aesthetic correction of alar-columellar disproportion. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1995;3:395-406.

Tardy ME, Heinrich JA, Linbeck EO. Refinement of the nasal tip. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;2: 459-476.

Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger RY, Key M. The cartilaginous pollybeak: etiology, prevention, and treaent. Fa;cial Plast Surg 1989:6:113-120.

Tardy ME, Patt BS, Walter MA. Transdomal suture refinement of the nasal tip: long-term outcomes. Facial Plast Surg 1989;9:275-284.

Tardy ME, Patt BS, Walter MA. Alar reduction and sculpture: anatomic concepts. Facial Plast Surg 1993;9: 295-305.

Tardy ME, Schwartz M, Parras G. Saddle nose deformity: autogenous graft repair. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6: 121-134.

Tardy ME, Thomas JR. Facial aesthetic surgery. Philadelphia : Mosby, 1995.

Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Alar retraction: composite graft correction. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6:101-107.

Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Philosophy and principles of rhinoplasty. In: Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker

LA, et al., eds. Otolaryngology-head & neck surgery. 2nd ed. St Louis : Mosby Year Book, 1993:278-294.

Tardy ME, Toriumi DM, Walter MA, Patt BS. The difficult nasal tip. In: Gates G., ed. Current therapy in oto‑ laryngology-head & neck surgery. 1993:170-182.

Tardy ME, Walter MA, Patt BS. The overprojecting nose: anatomic component analysis and repair. Facial Plast Surg 1993;9:306-316.

Tebbetts JB. Shaping and positioning the nasal tip without structural disruption: a new systematic approach. Plus/ Reconstr Surg 1994;94:61-77.

Thomas JR. Steps for a safer method of osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 1987;97:746-747. Thomas JR. External rhinoplasty: intact columellar approach. Laryngoscope 1990;100(2 Pt 1):206-208. Thomas JR, Griner NR, Remmler DJ. Steps for a safer method of osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 1987;

97:746-747.

Thomas JR, Tardy ME. Uniform photographic documentation in facial plastic surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1980;13:367-381.

Toriumi DM. Subtotal reconstruction of the nasal septum: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope 1994;104:906-13. Toriumi DM. Caudal septal extension graft for correction of the retracted columella. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;6:311-318.

Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault: operative techniques in plastic & reconstructive surgery 1995;2:16-30.

Toriumi DM. Surgical correction of the aging nose. Facial Plast Surg 1996;12:205-214.

Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Open structure rhinoplasty featured technical points and long-term follow-up. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:1-22.

Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Management of the lower third of the nose open structure rhinoplasty technique. In: Papel ID, Nachlas NE , eds. Facial plastic & reconstructive surgery. 1992:305-313.

Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger MS, Tardy ME. Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:802-808.

Toriumi DM, Mueller RA, Grosch T, Bhattacharyya TK, Larrabee WF. Vascular anatomy of the nose and the ex;ternal rhinoplasty approach. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1996;122:24-34.

Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative surgical management of the crooked nose. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993:1:63-78.

Toriumi DM, Sykes JM, Johnson CM. Open structure rhinoplasty for management of the non-caucasian nose. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;1:225-233.

Toriumi DM, Tardy ME. Cartilage suturing techniques for correction of nasal tip deformities. Oper Tech Oto;laryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;6:265-273.

Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger M, Tardy ME. Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:802-808.

Wang TD. Aesthetic structural nasal augmentation. Oper Tech Otolarvngol Head Neck Surg 1990.