Spreader Grafts

Spreader grafts may be placed endonasally or via the external rhinoplasty approach. If en donasal placement of spreader grafts is done in this dissection, undertake this before hump reduction and osteotomies.

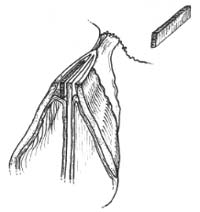

Through a small (5-mm) mucosal incision near the anterior septa] angle, develop a pre cise subperichondrial pocket along the length of the cartilaginous dorsum near the junction of the dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilage (Fig. 1). A Cottle or Freer elevator can be used to elevate the subperichondrial tunnels. Special care must be taken to get into the subperichondrial plane; otherwise, the mucosa may tear. Additionally, avoid pushing the elevator through the septum to the other side. Fashion rectangular spreader grafts that extend from the osseocartilaginous junction to the internal nasal valve where the upper lateral car tilage meets the dorsal septum. Appropriate thickness can be determined to achieve the de sired functional effect without causing excessive widening, usually I mm to 3 mm in thickness. Experience is required to develop reliable surgical judgment regarding the appropriate width and length of spreader grafts. Insert the grafts into the precise subperichondrial tunnels, taking great care to preserve the mucosa (see Fig. I ).

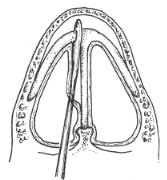

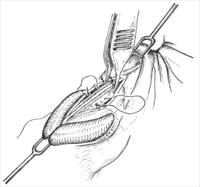

[Note: After placing endonasal spreader grafts, return to Chapter 6 and perform hump excision and then osteotomies. To examine the precise pocket that was made before hump removal, separate the upper lateral cartilage from the septum, as described below and illustrated in Fig. 2.]

Division of the upper lateral cartilages from their attachment to the dorsal septum is undertaken in the submucoperichondrial plane (see Fig. 2). This may be done before hump excision, or in cases in which no hump excision is necessary. Alternatively, this maneuver may be undertaken after hump excision. Again, great care should be taken to preserve an intact mucoperichondrium.

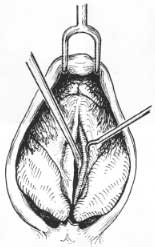

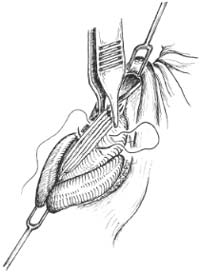

The accompanying figures (Figs. 2 through 6) illustrate placement of spreader grafts through the external rhinoplasty approach. At this point, the dissector should have under-taken hump reduction and osteotomies. (If hump removal has not been completed, return to Chapter 6). Spreader grafts are placed into pockets between upper lateral cartilage and dorsal septum (Figs. 3 and 4). A typical graft extends from the osseocartilaginous junction to the anterior septal angle. The spreader grafts are secured with absorbable suture [we rec ommend 5-0 polydioxanone suture WDS), Monacryl, or other similar suture.

Figure 1. A—D: Placement of spreader grafts via endonasal approach. A: Mucoperichondrial incision down to the cartilage. B: Careful elevation of subperichondrial tunnel. C: Spreader grafts. D: Insertion of spreader grafts.

Figure 2. A-G: Division of the upper lateral cartilages from their attachment to the dorsal septum in the submucoperichondrial plane. Great care should be taken to preserve an intact mucoperichondrium.

Figure 3. A: Spreader grafts are placed into a pocket between upper lateral cartilage and dorsal septum. A typical graft extends from the osseocartilaginous junction to the anterior septal angle. B: A spreader graft has been carved and is positioned between the dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilage.

Figure 4. A: Bilateral spreader grafts in submucoperichondrial pocket between upper lateral cartilage and septum.

Figure 5. Spreader grafts may be secured first with absorbable suture to the septum to stabilize them in position. (We recommend 5-0 PDS, or other similar suture).

Figure 6. Spreader grafts sutured into position. Several horizontal mattress sutures secure the spreader grafts and up-per lateral cartilages. A needle of adequate size (such as a PS-2) facilitates engaging all structures (upper lateral cartilage-to-spreader graft-to-septum-to-spreader graft-to-upper lateral cartilage) in a single pass. Note how this suture passes through the dorsal edge of the upper lateral cartilage.

The spreader grafts may be secured first to the septum to stabilize them in position (Fig. 5). Alternatively (and commonly), simply engage all structures (upper lateral cartilage-to-spreader graft-to septum-to-spreader graft-to-upper lateral cartilage) with a single mattress suture (Fig. 6). An additional horizontal mattress suture may be necessary to secure the spreader grafts and upper lateral cartilages in position. A needle of adequate size (such as a PS-2) facilitates en gaging all structures in a single pass (Fig. 6). Do not cinch down the mattress sutures too tightly or inferiorly, or else the upper lateral cartilages may actually be forced medially.

In the absence of other causes of nasal obstruction, the nasal valve and nasal valve area constitute the flow-limiting segment of the nose. The nasal valve is bounded by the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilage and the nasal septum, which join at an angle of 9 de grees to 15 degrees in the normal Caucasian nose (Fig. 7). A valve fulfills the definition of a movable structure that regulates the flow of gas or fluid. The nasal valve area includes the cross-sectional area described by the nasal valve and is affected by the inferior turbinate, the caudal septum, and the tissues surrounding the pyriform aperture (Fig. 7). The nasal valve area is considered to be the location of the least cross-sectional area in the nose and is believed to regulate significantly both nasal airflow and resistance and the velocity and shape of the air stream. The nasal valve area is the major flow-resistive segment of the nasal airway ( 1).

An overnarrow nose in the middle third, whether congenital or (more commonly) the consequence of previous surgery or trauma, requires cartilage graft augmentation to improve the airway and restore aesthetic balance. Examination may reveal an overnarrow an gle

Figure 7. Nasal valve and nasal valve area.

at the nasal valve area, medial collapse of the valve on even modest inspiration, or col lapse of the upper lateral cartilage against the septa] wall, effectively compromising the airway. Spreader grafts act as spacers between the upper lateral cartilage and septum, correcting an overnarrow middle vault and internal nasal valve or preventing excessive narrowing in the high-risk patient (2-10).

A submucoperichondrial tunnel on one or both sides of the dorsal aspect of the septum may be prepared by elevating the niucoperichondrium bridging the upper lateral cartilages to the septum. This dissection provides a space to be filled by a cartilage graft insinuated into the pocket, lateralizing the upper lateral cartilage(s), improving the airway and effectively widening, when indicated, the appearance of the middle third of the nose. In our experience, spreader grafts are more effective when the fibrous connections between the dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilage are left intact. Application of the spreader grafts creates a cantilever effect and aids in lateralizing the upper lateral cartilage to provide maximal airway improvement.

Whereas spreader grafts may be comfortably carried out through traditional endonasal techniques (2), in more complex reconstructions, particularly complicated by multiple abnormalities, an external rhinoplasty approach may facilitate accurate dissection and graft suture fixation (6).

When the T-shaped configuration (horizontal extension) of the nasal septum is resected with dorsal-hump removal, narrowing of the middle nasal vault may be problematic in the high-risk patient. Identifying the high-risk patient during initial preoperative analysis is essential to the prevention of excessive narrowing of the middle nasal vault with internal nasal valve collapse. An anatomic variant referred to as the “narrow-nose syndrome” has been described (2,6). Short nasal bones, long weak upper lateral cartilages, thin skin, and it narrow projecting nose predispose to muddle vault collapse. A large en bloc hump removal should be avoided, as the T-shaped horizontal support of the nasal septum is eliminated and the intranasal mucosa (which provides support to the upper lateral cartilage) is at risk of injury. Regardless of the approach to the middle vault, keeping the intranasal nwcosa intact with execution of profile alignment (dorsal-hump removal) helps maintain important support of the upper lateral cartilages (see Chapter 6, Fig. 5). This can be achieved by dissecting submucosal tunnels and freeing the upper lateral cartilages from the septum before cartilaginous hump removal. Alternatively, conservative hump excision followed by millimeter-by-millimeter shaving of the upper laterals under direct vision preserves the intranasal mucosa.

Collapse of the middle nasal vault may highlight the caudal edges of the nasal bones to produce the characteristic “inverted V” deformity (Appendix G).

When the dorsal hump has been taken down and the upper lateral cartilages appear destabilized, such as in the high-risk patient, suturing the upper lateral cartilages back to the septum can be helpful to prevent middle nasal vault collapse. Spreader grafts applied between the nasal septum and upper lateral cartilages prevent excessive narrowing of the nose and preserve an adequate nasal valve. An external rhinoplasty approach may facilitate accurate graft-suture fixation in this setting. These precautionary maneuvers are not necessary in all cases but may prevent problems in the high-risk patient (6).

Commonly performed surgical maneuvers can result in loss of support to the middle vault. Cephalic trim (volume reduction) of the lateral crura disrupts the scroll (recurvature) and frees the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage. Lateral osteotomies may further medi alize the upper lateral cartilages. The upper lateral cartilages can fall toward the narrowed dorsal septa] edge, producing narrowing of the middle vault and internal valvular collapse. In the majority of patients, the combination of these maneuvers will not result in a problem; however, in high-risk patients (narrow-nose syndrome), this combination of maneuvers 4 nay contribute to excessive narrowing of the middle vault with internal valve collapse.

When spreader grafts are used, appropriate spreader-graft thickness will achieve the de-sired functional effect without causing overwidening. Great care should be taken to avoid overwidening if possible. Experience is required to develop reliable surgical judgment regarding the appropriate width and length of spreader grafts. Careful palpation of both up-per lateral cartilages can aid in verifying symmetry of the middle nasal vaults.

Spreader grafts are usually ]rain to 3 nun in thickness. It is generally better to use thinner spreader grafts because if the middle vault is too wide, revision rhinoplasty surgery will be necessary. After spreader grafts are secured in position via the external approach, or if they are placed endonasally after dissection of the soft-tissue envelope, the middle-vault width can be assessed by inspection and palpation. The middle vault should be no wider than the bony vault and nar r ower than the nasal tip. If excessive width or asymmetry is noted, the grafts should be repositioned or narrowed. Over time, this area of the nose tends to narrow as edema resolves and scar contracture pulls the upper lateral cartilages medially.

Asymmetry of the middle nasal vault may at times be addressed with the placement of a unilateral spreader graft, or alternatively, with the placement of spreader grafts of unequal thickness (Fig. 8) (10). In most cases, we prefer to use bilateral spreader grafts to splint deviations of the dorsal septum and prevent worsening of the dorsal septal deviation.

A variety of other maneuvers are at the surgeon’s disposal in addressing the middle nasal vault. Onlay cartilage wafer grafts, derived from the septum or ear, effectively efface and improve middle-third depressions, but may be used to improve aesthetics only when airway blockage does not exist as a consequence of middle-vault collapse. Careful preoperative analysis should determine the need for other supportive and reconstructive maneuvers, such as conchal cartilage grafts to restore support to a collapsed lateral nasal wall. External valve collapse and the potential need for alar batten grafts also should be evaluated.

Figure 8. Spreader grafts may be applied unilaterally or asymmetrically to camouflage asymmetry of the middle nasal vault.

Figure 9. Coronal sinus computed tomography scan in a patient with nasal obstruction, illustrating obstructing concha bullosa.

PEARLS

If there is difficulty in spreader-graft placement by using an external approach, check the exposure. A common mistake is a failure to carry the marginal incision and dissection over the lateral crura laterally enough, limiting exposure. Extending this incision and dissection appropriately will improve exposure of the middle nasal vault and greatly facilitate spreader-graft placement.

Double check middle-vault width and symmetry after applying spreader grafts. Careful palpation will allow precise assessment of middle-vault width.

Spreader grafts applied into precise submucosal tunnels introduce bulk under the intact connection between the upper lateral cartilage and dorsal septum. The spreader graft creates a cantilever effect and effectively lateralizes the collapsed upper lateral cartilage.

When securing spreader grafts via suture fixation, gently stretch the upper lateral cartilage toward the anterior septal angle to ensure that they are not buckled. The suture will place gentle traction on the upper lateral cartilages to prevent buckling. After completing suture fixation, inspect the upper lateral cartilages to be sure that they are not buckled (6).

In considering nasal obstruction, a complete evaluation is critical. Causes of nasal obstruction include allergic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, rhinitis medicamentosa, nasal polyps, deviated septum, internal and external nasal-valve collapse, and others. One commonly overlooked cause of nasal obstruction is a concha bullosa, or aerated middle turbinate (Fig. 9), which can be most easily recognized on nasal endoscopy or coronal computed tomography scan.

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME. Survcal onutnmrr of the nose. New York: Raven, 1990.

- Sheen JN. Spreader graft a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plasv Reconstr Surg 1984;73:230-237.

- Goode RL. Surgery of the incompetent nasal vale. L.crry , gONCope 1985:95:546-555.

- Johnson CM. Toriumi DM. Open structure rhinoplasty. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990.

- Toriumi DM. Johnson C.M. Open structure rhinoplasty: featured technical points and long-term follow-up. Fticial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:1-22

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault in rhinoplasty. Oper Tech Plast Recon.str.Surt; 1995;2: 16-30.

- Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting air- way obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Phut Reconstr Surg 1996;98:38-54.

- Teichgraeber JF, Wainwright DJ. The treatment of nasal valve obstruction. Pla.ct Reconsvr Surg 1994;93: 1174-1184.

- Aiach G. Atlas rte rhinoplastie. Paris: Masson, 1989:74-85.

- Toriumi DM. Ries WR. Innovative surgical management of the crooked nose. Facial Plast .Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:63-78.