The authors have no relevant financial disclosures or conflicts of interests to disclose. No funding or external support was provided for the development of this manuscript.

Abstract

Nasal airway obstruction is one of the most common complaints seen by otolaryngologists and the septoplasty is one of the most common operations performed. Despite this, many patients are still dissatisfied with their nasal breathing often due to a failure to adequately address the internal nasal valve. The butterfly graft is one of the most powerful techniques to open the internal nasal valve, particularly the apex. The historical concerns regarding the aesthetics of the graft have been addressed through precise shaping of the graft, and it now presents a first line treatment option for improving internal nasal valve stenosis and collapse.

Keywords: butterfly graft, nasal airway obstruction, internal nasal valve, nasal valve stenosis, rhinoplasty, septorhinoplasty

Introduction

Nasal airway obstruction is one of the most common reasons patients seek consultation with an otolaryngologist, and the septoplasty is the third most common operation performed by otolaryngologists1. Despite this, up to one-third of patients are dissatisfied with their postoperative breathing result2. 67% of those being evaluated for primary nasal airway surgery, and 82% of those being evaluated for revision nasal airway surgery, have some level of nasal valve insufficiency3. This underscores the high prevalence of nasal valve stenosis and the relative undertreatment of one of the most critical areas of the nasal airway.

The use of composite grafts to augment nasal breathing was first described by Claus Walter in 19694. Stucker then described a conchal cartilage overlay for the correction of nasal valve and lateral nasal collapse in 19945. In 2002, Clark and Cook pioneered the “butterfly” graft for use in revision rhinoplasty6. Since that time, the butterfly graft has undergone additional advances which have transformed it from a second line treatment in revision cases to a first line treatment for internal nasal valve insufficiency7-10. This chapter will describe the use of the butterfly graft for the correction of nasal valve stenosis.

Anatomy and Physiology

In discussions of the nasal valve, it is important to distinguish between the internal and external nasal valve regions. The evaluation and approach to treatment of these two entities is distinctly different; therefore, precise definitions are needed to help guide surgeons. Most commonly, the internal nasal valve is described as the cross-sectional area formed by the caudal border of the upper lateral cartilage, the dorsal septum, the head of the inferior turbinate, and the nasal floor11. The internal nasal valve is part of the “superior corridor” of the nose, defined as the three-dimensional area superior to a horizontal line drawn from the septum to the insertion of the inferior turbinate on the lateral nasal wall (Figure 1). It is this region which accounts for the majority of nasal airflow resistance, and therefore has the biggest impact on a patient’s ability to breathe.

In the internal nasal valve, the angle formed at the apex of this triangle is classically described as being between 10 to 15 degrees12. Although the cross-sectional area of the internal nasal valve averages only 40-60mm2, it accounts for between one-half and two-thirds of the total nasal airway resistance2,11,13. The physical forces that impact nasal breathing during inspiration can be summarized by two principles of physics. Poiseuille’s law states that the volumetric flow rate through a chamber is inversely proportional to the radius of the chamber to the fourth power. This explains why small changes in the area of the internal nasal valve create large changes in the patient’s nasal airflow. The Bernoulli effect describes the relationship between air flow and pressure. It demonstrates that as the velocity of airflow increases within a tube, the luminal pressure in the walls of the tube decreases. In the nose, this translates to a dynamic collapse of the lateral nasal sidewalls if the drop in luminal pressure caused by the passage of air is greater than the strength of the upper lateral cartilages and soft tissue envelope. In order to maintain adequate nasal patency during inspiration, the internal nasal valve must have a sufficient “radius,” or cross-sectional area, as well as have adequate stiffness of the lateral nasal sidewall to resist the drop in pressure. If either, or both, of these conditions do not hold true, then nasal airway obstruction occurs.

Techniques to Manage the Internal Nasal Valve

Over the years, various techniques have evolved to manage a narrowed internal nasal valve12. The most common method is the use of spreader grafts, first introduced in 1984. These cartilage grafts are used as spacers between the dorsal septum and upper lateral cartilages14. Although if properly placed, these can improve a statically narrowed valve space, they do not offer much added strength to the lateral nasal sidewalls. In fact, the disarticulation of the attachment of the upper lateral cartilage to the dorsal septum would be expected to weaken the strength of the lateral nasal sidewall. A more recently described, but similar approach in cartilage depleted noses is the use of autospreader or turn-in flaps. Similar to spreader grafts, these have not been proven to increase the stiffness of the lateral nasal sidewall. These techniques are designed to address static narrowing. In patients with limited dynamic collapse of the nasal sidewall, alar batten grafts have been used to provide added strength. More recently, the use of bioabsorbable lateral nasal wall stents have been developed to similarly aid in stiffening a weak lateral nasal wall from collapse15. In an effort to address both the static and dynamic forces in the internal nasal valve, flaring sutures were first described by Park16. Clark and Cook then described the technique for addressing both the static and dynamic insufficiency of the nasal valve, the butterfly graft. To date, cadaver studies suggest that the butterfly graft is the most robust method for nasal valve repair17.

In the senior author’s experience, the most critical part of the internal nasal valve is the apex (the acute angle formed by the articulation of the dorsal septum and the upper lateral cartilage – see diagram). Unfortunately, the most common approach (septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction) to surgery often addresses only the inferior corridor. On the contrary, the butterfly graft’s primary effect is seen (by the surgeon) and felt (by the patient) along the apex of the internal nasal valve, thereby addressing the critical superior corridor.

Patient Selection

The butterfly graft is a surgical option for patients with subjective complaints of nasal airway obstruction and objective findings internal nasal valve collapse, whether dynamic or static, and in primary or secondary cases6-8,10. Evaluation begins with a comprehensive medical history. Pertinent history to obtain includes laterality and duration of obstruction, impact on quality of life including sleep and exercise, presence of chronic rhinosinusitis, presence of allergic rhinitis, prior nasal or facial traumas, prior surgeries – especially nasal, sinus, or facial, and any trials of saline irrigations and nasal steroid spray. Special note is made of any trial of external nasal dilator strips (e.g. “Breathe Right Strips”) and the effect of this on nasal breathing at rest, during exercise, and during sleep. Improvement in nasal breathing with the use of nasal strips is a helpful predictor of an increased likelihood of success with the use of the butterfly graft. The converse is not necessarily true, however, as even patients who do not respond to nasal strips often report dramatic improvement after butterfly graft placement. This paradoxical finding is often due to improper usage of the nasal strips, and with instruction in proper placement, most patients with internal nasal valve stenosis will report significant improvement. Additionally, there are patients with unique anatomic or structural features which make using the nasal strips difficult including extremely sebaceous skin, tension nose deformity, or upper lateral cartilages with significant stiffness. The judgement of the surgeon should be used to determine if an adequate trial of nasal strips can be undertaken, and the response should be interpreted in the context of the physical examination of the nasal anatomy.

A complete head and neck exam should be undertaken in every patient, including a thorough nasal analysis. This should also include evaluation for relative deficiency of the maxilla or midface retrusion, as well as the overall peri-nasal muscle integrity and symmetry. Externally, the width of the midvault should be noted, as should any dorsal line deviations and the overall straightness relative to the intercanthal and interincisor midlines. The presence of scars and the thickness of the skin-soft tissue envelope is also important to note for planning purposes. Anterior rhinoscopy will reveal septal deviations and the presence and contribution of inferior turbinate hypertrophy. A Cook, or modified Cottle, maneuver should be performed and documented on every patient to determine the subjective response to upper lateral cartilage repositioning. If indicated, a nasal endoscopy should be performed to rule out posterior septal deviations or other sinonasal pathology.

The only absolute contraindication to butterfly graft placement is a history of prior ear surgery, trauma, or malformation bilaterally with lack of available auricular cartilage for grafting. The authors do not use septal or costal cartilage for the butterfly graft. All patients must be advised of the likelihood of increased supratip width post-operatively. As with spreader grafts, there is an inherent increase in width18,19. Special care is advised in patients who are more cosmetically sensitive than average with slender noses or very thin skin. With appropriate modifications, the graft is most often not visible even to medical professionals8, however the additional width at the supratip may not be acceptable in some patients and should be discussed preoperatively.

Technique7

Auricular Graft Harvest

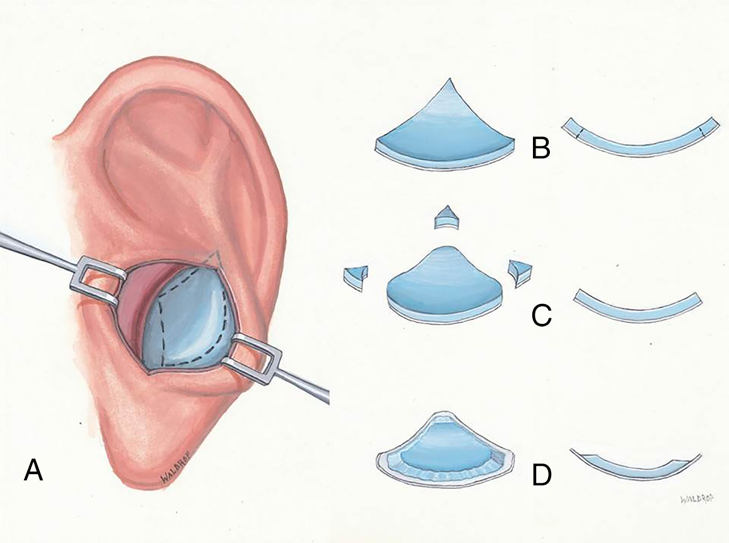

The butterfly graft is usually performed under general anesthesia. The procedure begins with harvesting of the auricular cartilage. Local anesthesia (a 1:1 combination of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine and 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine) is injected into the subperichdonrium on the anterior surface of the cartilage and subcutaneously on the posterior auricular surface. This allows the posterior perichondrium to remain firmly adherent to the cartilage. A curvilinear incision is made along the medial aspect of the antihelix with a small back cut made into the conchal bowl in a natural crease just above the antitragus. The conchal cartilage is exposed, taking care to avoid fractures or inadvertent cuts in the cartilage. Once the anterior surface of the graft is exposed, a #15 blade is used to incise the cartilage and posterior perichondrium. Dissection posteriorly occurs in a supraperichondrial plane until the graft is completely freed and placed in saline for carving. The average initial size of harvested graft is approximately 2.5×1.5cm, although with experience the graft harvest size is often smaller. Figure 2 shows the auricular harvest site and the typical carving pattern.

The auricular graft is then carved to fit the individual patient’s nasal shape and strength needs. Graft planning begins by avoiding fractured or palpably weak areas and incorporating natural symmetric flexion points. Noting the width of the patient’s middle nasal vault, the ideal horizontal length is estimated to generate optimal flexion. Graft strength can be assessed by flexing it between the thumb and index fingers. If the graft is overly strong, gently and progressively weakening it using Brown-Adson forceps or a cartilage morselizer can help to provide the desired “spring.” If the patient has a side with a weaker upper lateral cartilage or a side that is more narrow, the stiffer half of the butterfly graft is planned to be placed on that side. The edges of the cartilage are beveled, taking care to leave the posterior perichondrium intact. This creates a ledge of perichondrium with no underlying cartilage which can be used to camouflage the relief of transition zones between the graft and native nose – especially laterally and along the margin of the graft superiorly. After carving is completed, the graft on average measures 1.8 x 0.9 cm, but varies according to the patient’s anatomy.

Nasal Approach

The septoplasty and, if indicated, turbinate reductions are then completed. If using an endonasal approach, an intercartilaginous incisions are made bilaterally. The skin and superficial musculoaponeurotic system envelope is then elevated off of the upper lateral cartilages up to the level of the rhinion on the patient’s right side. This plane of dissection is carried over the dorsum to connect to the left intercartilaginous incision. A similar dissection is carried out on the left side. Once atraumatic elevation of the skin-soft tissue envelope over the mid nasal vault is completed, a subperiosteal dissection is performed cephalic to the nasion to allow better redraping of the soft tissue envelope over the cephalic border of the graft.

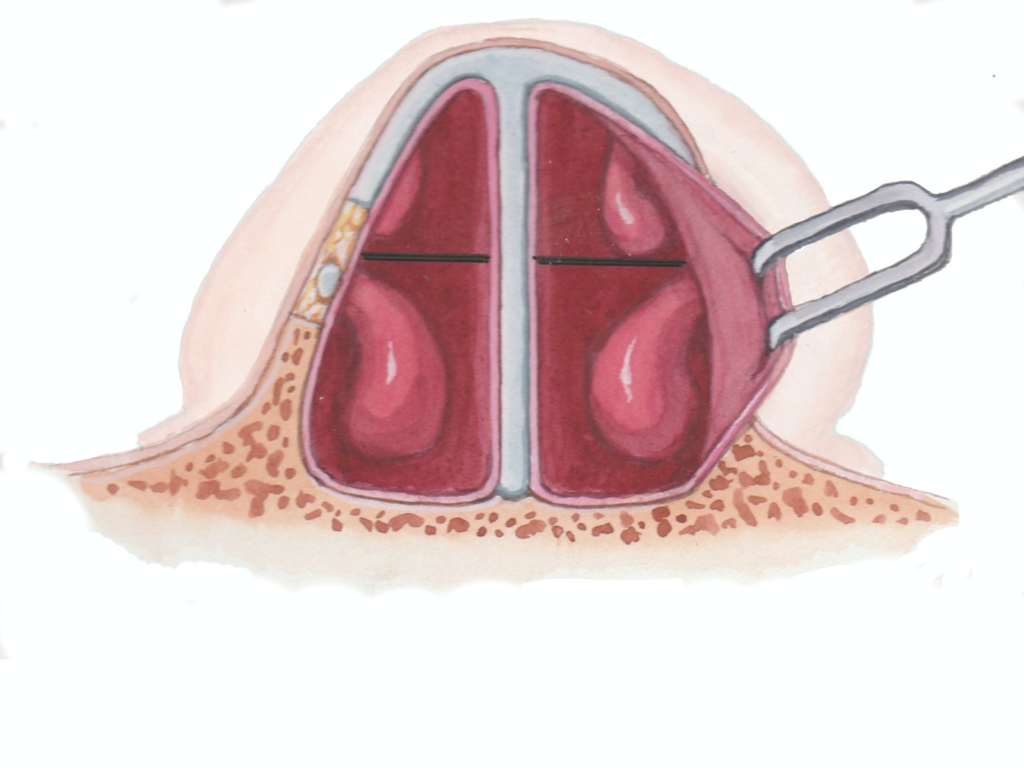

Under visualization, a #15 blade is used to create a depression in the dorsal septum that extends from the rhinion to the anterior septal angle. This depression begins shallow at the cephalic end, and deepens towards the scroll region to allow for the thickness of the butterfly graft (Figure 3). The upper lateral cartilages are then released from the dorsum if this was not accomplished with the dorsal reduction. This allows for better repositioning of the upper lateral cartilages by the butterfly graft and generating an even greater widening of the valve angle.

Graft Placement

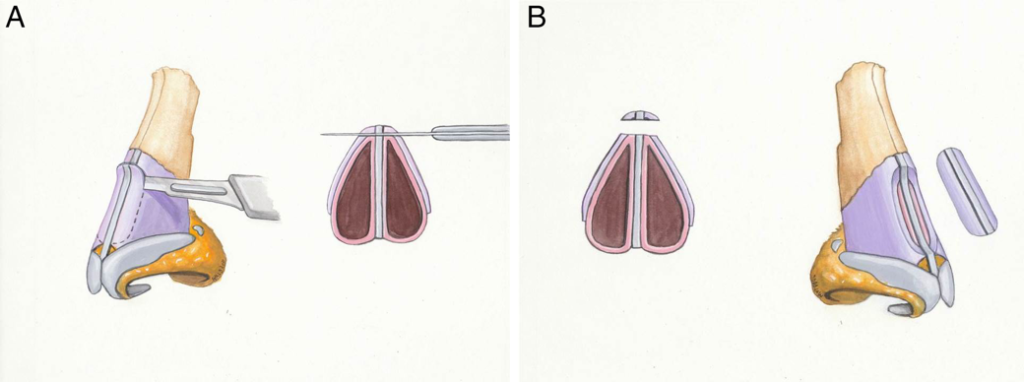

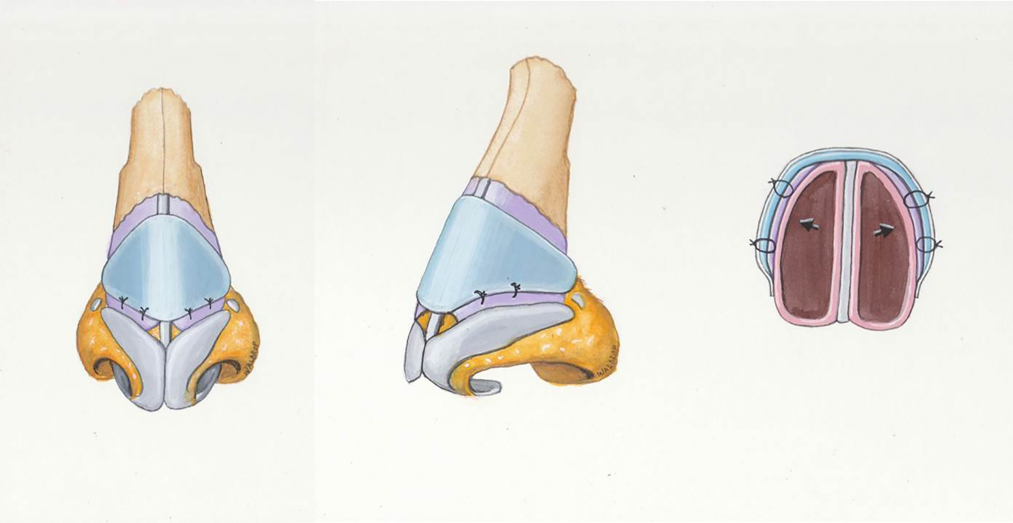

The graft is then inserted through the right intercartilaginous incision and passed so that it straddles the septum with its cephalic margin at the caudal border of the nasal bones and the caudal margin at the scroll. The graft is first secured medially using 5-0 polydioxanone sutures on a P-2 needle. At the very apex of the internal nasal valve angle, the needle is passed from the deep aspect of the medial upper lateral cartilage and through the butterfly graft, making sure to include the perichondrium of the graft in the bite. This helps to prevent cheese-wiring through the graft during knot placement. Next the graft is secured medially on the contralateral side in similar fashion, making sure to place the graft on tension across the septum. This allows the graft to use the septum as a fulcrum point for the lateral extensions. The lateral sutures are then placed at the lateral-most aspect of the upper lateral cartilage that the graft will reach (Figure 4). Again, the graft is placed on tension prior to securing it to the upper lateral cartilages.

The skin and soft tissue envelopes are then replaced and the external contour evaluated for any unwanted fullness at the lateral extent of the graft. If needed, the graft can be trimmed in situ. If there is an apparent step off at the rhinion, small cartilage fragments from carving of the graft may be morselized to provide a smoother dorsal contour.

The intercartilaginous incisions are then closed using a 5-0 chromic on a P-2 needle and the dorsum is dressed with adhesive and paper tape. If osteotomies have been performed, a thermoplastic splint is also applied.

Open Approach

The butterfly graft may also be placed through an open approach utilizing similar techniques as the closed approach (Figure 4). However, if there is manipulation of the lower lateral cartilages, these should be resuspended superficial to the graft to aid in its camouflage.

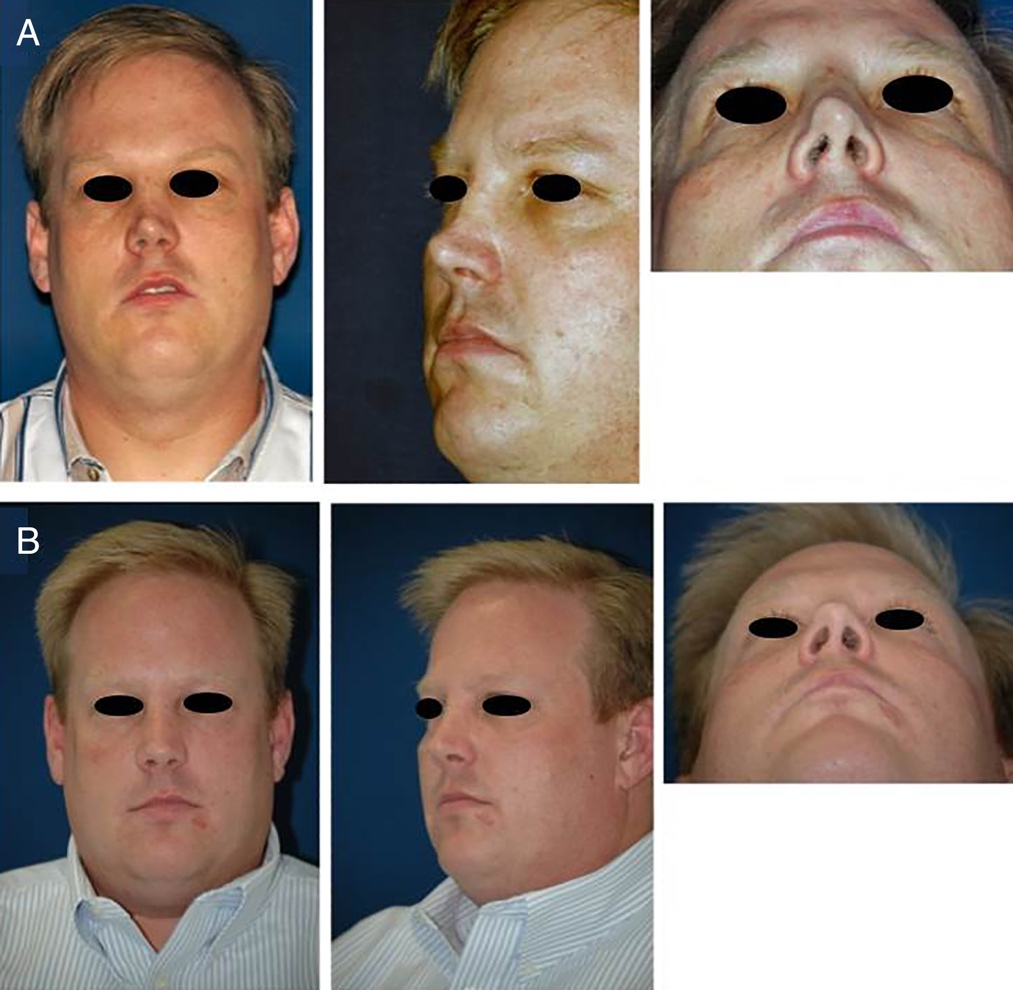

Postoperative Care

The Telfa bolster is removed from the ear on the first postoperative day and the ear is inspected to ensure no hematoma is present. The antihelical incision is then cleaned and antibiotic ointment applied. The nasal cavities are similarly cleaned and suctioned on the first postoperative day to allow for improved breathing and ability to deliver saline and steroid nasal sprays in the initial postoperative period. Saline irrigations and steroid nasal sprays are used twice daily for 10 to 14 days, and then once daily for a total of three months postoperatively. Figure 5 demonstartes a patient pre-operatively and with 8 year post-operative follow up.

Discussion

The nasal butterfly graft is designed to address a common area of nasal obstruction in both the primary and revision settings. In the largest series of 512 patients, 87% of patients experienced complete resolution of their nasal obstruction with an additional 10% reporting at least partial improvement. No patients reported worsening of nasal breathing postoperatively7.

To better understand how it improves nasal breathing computational fluid dynamics was used to compare the effect of the butterfly graft to the more classic spreader grafts in a head to head study using cadaveric models17. This study found the butterfly graft to provide up to twice as much reduction in nasal airflow resistance compared to the spreader grafts. Wall pressure plots were mapped using the computational fluid dynamic model which also demonstrated that the butterfly graft had its greatest effect compared to the spreader grafts in the nasal valve area.

A common area of concern for the butterfly graft is the visibility of the graft postoperatively. Using the original technique, a minority of patients reported worsening of aesthetic outcomes6,10. This is thought to most commonly be related to a discrete dorsal hump from the graft, and supratip fullness. Chaiet and Marcus examined their cases and found an average increase in supratip width by 6.4% and an average increase in supratip projection by 8.5%20. In order to improve this, Howard and Clark reported on modifications to the original technique which aim to better camouflage its appearance and improve its performance. These changes include careful contouring of the graft to fit the patient’s nasal anatomy with beveling of the graft edges, lowering of the dorsum so that the graft can sit flush with the dorsal line, and release of the upper lateral cartilages from the dorsal septum. When comparing aesthetic outcomes early in the senior author’s experience (prior to implementation of the current modifications) to those of his later experience, patients undergoing butterfly graft placement with the current modifications reported higher rates of satisfaction with their postoperative appearance. Of these more recent patients, 94% reported their appearance as either unchanged or improved7. Others have similarly found that smaller, more contoured grafts that are more caudally positioned have improved aesthetics21.

Complications

Similar to other nasal airway surgeries, the butterfly graft carries with it a favorable complication profile. The most common complications include auricular hematoma (5.3%) and local wound infections (2.9%)7. Auricular hematomas can be diagnosed and addressed in the clinic through the prior incision site on postoperative day one. Wound infections respond well to antibiotics and, if needed, drainage. The only reported butterfly graft to become dislodged was secondary to a motor vehicle collision7.

Conclusion

The nasal butterfly graft is a powerful technique to manipulate the internal nasal valves for patients with nasal airway obstruction. It continues to advance with new modifications and can be considered as a first line treatment for nasal valve stenosis.

Reference List

- Casey KP, Borojeni AA, Koenig LJ, Rhee JS, Garcia GJ. Correlation between Subjective Nasal Patency and Intranasal Airflow Distribution. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(4):741-750.

- Siegel NS, Gliklich RE, Taghizadeh F, Chang Y. Outcomes of septoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(2):228-232.

- Clark DW, Del Signore AG, Raithatha R, Senior BA. Nasal airway obstruction: Prevalence and anatomic contributors. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97(6):173-176.

- Walter CD. Composite grafts in nasal surgery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1969;90(5):622-630.

- Stucker FJ, Hoasjoe DK. Nasal reconstruction with conchal cartilage. Correcting valve and lateral nasal collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(6):653-658.

- Clark JM, Cook TA. The ‘butterfly’ graft in functional secondary rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(11):1917-1925.

- Howard BE, Madison Clark J. Evolution of the butterfly graft technique: 15-year review of 500 cases with expanding indications. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(S1):S1-S10.

- Loyo M, Gerecci D, Mace JC, Barnes M, Liao S, Wang TD. Modifications to the Butterfly Graft Used to Treat Nasal Obstruction and Assessment of Visibility. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016;18(6):436-440.

- Genther DJ, Wang TD. Modification of the Butterfly Graft. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(6):509-510.

- Friedman O, Cook TA. Conchal cartilage butterfly graft in primary functional rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(2):255-262.

- Rhee JS, Weaver EM, Park SS, et al. Clinical consensus statement: Diagnosis and management of nasal valve compromise. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143(1):48-59.

- Barrett DM, Casanueva FJ, Cook TA. Management of the Nasal Valve. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016;24(3):219-234.

- Schlosser RJ, Park SS. Functional nasal surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1999;32(1):37-51.

- Motamedi KK, Stephan SJ, Ries WR. Innovations in nasal valve surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;24(1):31-36.

- Sanan A, Most SP. A Bioabsorbable Lateral Nasal Wall Stent for Dynamic Nasal Valve Collapse: A Review. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(3):367-371.

- Park SS. The flaring suture to augment the repair of the dysfunctional nasal valve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(4):1120-1122.

- Brandon BM, Austin GK, Fleischman G, et al. Comparison of Airflow Between Spreader Grafts and Butterfly Grafts Using Computational Flow Dynamics in a Cadaveric Model. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(3):215-221.

- Stacey DH, Cook TA, Marcus BC. Correction of internal nasal valve stenosis: a single surgeon comparison of butterfly versus traditional spreader grafts. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63(3):280-284.

- Fuller JC, Levesque PA, Lindsay RW. Analysis of Patient-Perceived Nasal Appearance Evaluations Following Functional Septorhinoplasty With Spreader Graft Placement. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019;21(4):305-311.

- Chaiet SR, Marcus BC. Nasal tip volume analysis after butterfly graft. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(1):9-12.

- Loyo M, Markey JD, Gerecci D, et al. Technical Refinements and Outcomes of the Modified Anterior Septal Transplant. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(1):31-36.