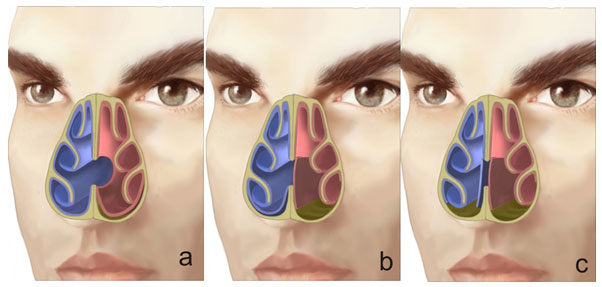

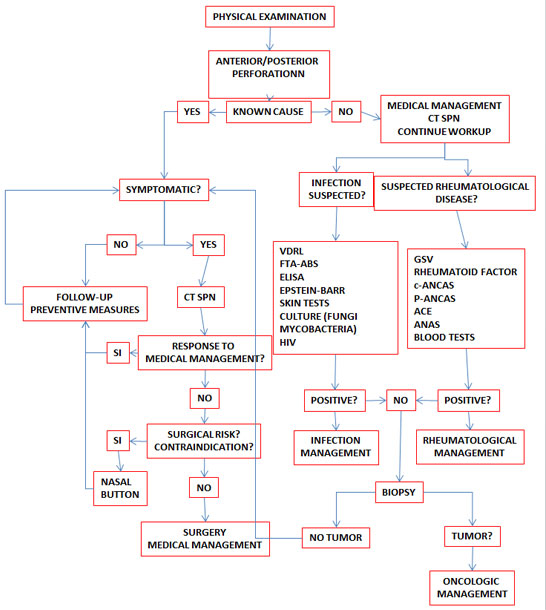

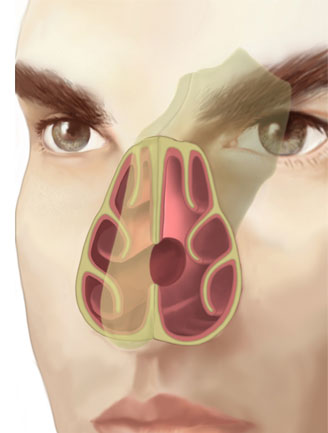

A perforation of the nasal septum is considered a continuity defect in any bone or cartilage portion of the septum, with absence of the mucoperichondral or mucoperiosteal lining. It is often asymptomatic, but it may give rise to multiple uncomfortable symptoms that eventually lead patients to seek help. (Fig. 1)

The diagnosis and etiology of septal perforations pose a challenge, but more challenging still is to determine the medical or surgical interventions required to achieve final closure or to prevent the defect from growing so as to restore the normal nasal physiology.

Sometimes it is not possible to identify the cause of the perforation, and there is considerable variation in the literature regarding the rates of success using the different closure techniques.

The prevalence of septal perforations is estimated at 0.9% (1). So far, no relationship has been found between this condition and factors such as age, gender or geographic location.

It is well known that the majority of septal perforations are of iatrogenic origin, with a reported prevalence ranging from a low of 1% to a high of 25%. The highest rates are found to occur with the submucosal resection technique described by Killian(2) but, otherwise, they are dependent on the skills of the surgeon.

Etiology

Because there are other conditions associated with septal perforations (Table 1), it is important to identify the cause before choosing surgical management, thus reducing the probability of reperforation.

The nasal septum is rich in blood flow coming from branches of the internal and external carotid arteries. When bilateral blood flos is compromised in certain conditions, the mucoperichondrium is affected and cartilage necrosis occurs rapidly, leading to perforation. A different situation occurs as a result of nasal submucosal resection and/or contiguous tears of both mucose tissues during surgical procedures such as septoplasty. Commonly, the bloody area on the internal border of the perforation epithelizes, preventing the natural closure of the defect. (4).

| Trauma

Inflammatory causes

Infections

| Neoplasms

Other causes

| Table 1. Known causes of septal perforation (2,3,4,6,7,8) | ||||

| Trauma

Inflammatory causes

Infections

| Neoplasms

Other causes

| ||||||

| Table 1. Known causes of septal perforation (2,3,4,6,7,8) | |||||||

Pathophysiology

Air flow inside the nasal cavity is known to be a key determining factor of nasal functions such as the sense of smell, and filtration, warming and humidifying of inspired air. (9)

It has also been reported that temperature and humidity changes in the environment might influence the flow pattern, altering its velocity and turbulence. (10)

Although most patients do not present specific symptoms, the air flow alteration that occurs in perforations of the anterior portion of the septum manifest with rhinosinus symptoms. (11,16) These symptoms are very similar to those found in patients with allergic rhinitis, septal deviation and chronic rhinosinusitis. It is estimated that close to 57% of patients with perforations may have chronic rhinosinusitis, although this does not necessarily imply that symptoms may get worse. (12) This means that when symptoms warrant it, it is necessary to rule out the presence of rhinosinusitis associated with the finding of a septal perforation.

Posterior perforations tend to cause less symptoms due to the humidifying effect provided by the nasal mucosa and the turbinates. (Table 2)

| SYMPTOMS OF NASAL PERFORATION |

| Table 2. Symptoms in patients with septal perforation | |||

| SYMPTOMS OF NASAL PERFORATION | ||||||

| ||||||

| Table 2. Symptoms in patients with septal perforation |

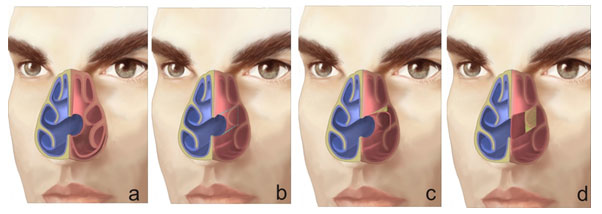

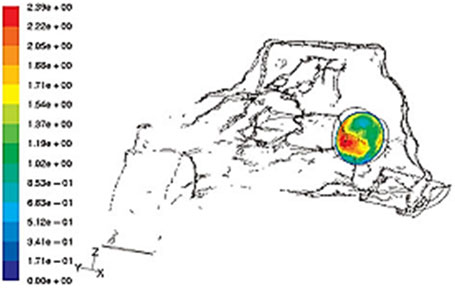

There are only few studies that assess the behavior of nasal airflow patterns when there is a perforation. Lee et al. used a 3D reconstruction computer model and magnetic resonance data to assess the effect of the airflow pattern in relation to the size of the septal perforation. (13) The study showed that the peak velocity and stress created by the airflow current occurred at the lower end of the perforation. (Fig. 2) This finding correlates with dryness, scab formation and typical bleeding in that area.

When airflow appeared to “bump” against the posterior border of the perforation, it created a turbulence that increased with the size of the perforation. The altered distribution of airflow and temperature through the perforation favors mucosal dryness and, eventually, scab formation.

Symptoms are also influenced by the size of the perforation. In large perforations, the altered airflow distribution pattern may create a sensation of obstruction. When the perforation is small (less than 5mm), the volume of airflow passing through it is also small, giving rise to the typical wheezing sound that occurs with normal breathing. (13)

Pain may also be present and, in those cases, it may be suggestive of perichondritis. This usually happens around the circumference of the perforation and is very often associated with the patient’s hygiene.(4)

Finally, the progression of an anterior lengthening of the perforation might eventually compromise the dorsal and caudal buttressing of the nose. The impact is no longer a functional problem of nasal obstruction due to vestibular stenosis or collapse of the internal nasal valve, but also a cosmetic problem due to nasal tip collapse and/or a saddle deformity.(4)

Clinical Assessment

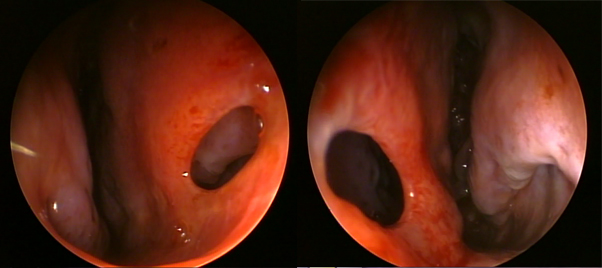

A thorough assessment requires removal of the scabs and vasoconstriction of the inferior turbinate in order to visualize the entire nasal septum with the use of an endoscope. Posterior perforations may be missed in cases of septal deviation or long hypertrophic turbinates. Once the perforation is identified, its size and relative location must be documented. (3)

In terms of size, perforations are classified as small (less than 1 cm), medium (1-2 cm) or large (greater than 2 cm). (11,17) Determining the size is important for the selection of the surgical management and/or technique to be used. According to their location, perforations are classified as anterior (from the anterior nose to the head of the middle turbinate), posterior (from the head of the middle turbinate to the choana), low (close to the nasal floor), or high (close to the dorsum). (4,12) (Table 3) Nearly 75% of all perforations are reported to be in an anterior location, well circumscribed and smaller than 2 cm.(14)

| BY SIZE | BY LOCATION | Small – < 1 cm Medium – 1-2 cm Large – > 2 cm | Anterior – anterior nose to the head of the middle turbinate Posterior – from the head of the middle turbinate to the choana Low – close to the nasal floor High – close to the nasal dorsum | Table 3. Perforation classification according to size and location | ||||||

| BY SIZE | BY LOCATION | ||||||||||

| Small – < 1 cm Medium – 1-2 cm Large – > 2 cm | Anterior – anterior nose to the head of the middle turbinate Posterior – from the head of the middle turbinate to the choana Low – close to the nasal floor High – close to the nasal dorsum | ||||||||||

| Table 3. Perforation classification according to size and location | |||||||||||

When the perforation is not uniformly round, it is useful to measure the vertical height as well as the horizontal length. The vertical height of the perforation plays a key role in determining the success of the surgery, more so than the horizontal length, because of its more direct effect on the tension between the floor and the dorsum of the nose. (4,15)

When scabs are found not only around the edges of the perforation but also throughout the septal and turbinate mucosa, the presence of a granulomatous or vasculitic process must be ruled out. The presence of scabs or of a granulomatous process in a cocaine user compromises long-term prognosis, because of the high risk of reperforation.

The septum must be palpated with the help of a cotton tip in order to determine the presence of cartilage between the mucosal flaps and whether the cartilage extends up to the edges of the perforation. In perforations secondary to surgical procedures such as septoplasty, there may be little cartilage remaining, making it more difficult to perform the dissection in an attempt to correct the defect. If there is extensive membrane formation and inflammation, or if there is evidence of synechiae or internal or external nasal collapse, an active inflammatory process or cocaine use must be suspected. Usually, in cases of perforation due to cocaine use, the edges of the perforation are clean, with exposed cartilage around most of the edge. The more mucosal swelling and the more scabs there are present around the perforation, the higher the suspicion of a generalized systemic problem.(3)

With thorough questioning, the cause of the perforation may become evident (trauma, surgery, occupational exposure, personal habits, use of recreational drugs, topical or systemic medications).

There have been reports of nasal perforations associated with the chronic use of topical nasal steroids, oxymetazoline and phenylephrine(2), and also with the use of antineoplastic agents such as Bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) monoclonal antibody affecting the formation of normal and pathological blood vessels. The proposed mechanism for the perforation is the prior existence of a local irritation with a mucosal disruption that does not heal properly due to the effect of the medication. This situation is compounded by the anti-angiogenic and immunosupressive action of the chronic use of corticosteroids. (7,8)

Patients with a septal perforation from no apparent cause are the biggest diagnostic challenge. It is important to try to rule out a systemic disease before labeling the perforation as idiopathic because this will be of critical importance in determining a treatment plan.

Workup must begin with a CT scan in order to rule out sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis or other granulomatous diseases. Patients with negative head-and-neck clinical findings and a normal CT scan will require additional assessment with laboratory tests to look for collagen, vascular and renal diseases. (3)

A high globular sedimentation velocity value may be indicative of a rheumatological disorder but, unfortunately, a value within the reference range does not rule out that kind of pathology. This value is significantly higher in dermatomiositis and polymyositis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), lupus, Wegener’s granulomatosis, temporal arteritis and other disorders. The rheumatoid factor (RF) may be elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, connective tissue diseases, lupus and scleroderma. Patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis present with cough, hemoptysis, sinusitis, rhinorrhea and/or ocular disorders (episcleritis, conjunctivitis).

This disease is often associated with high anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA), high globular sedimentation velocity (GSV) and high rheumatoid factor (RF) values, although the latter is less specific. High angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) values together with high serum calcium levels should lead the clinician to suspect the presence of sarcoidosis. On chest X-rays, these patients usually show mediastinal lymph node disease. Cases of Churg-Strauss syndrome are identified on the basis of high anti-neutrophil perinuclear antibodies (p-ANCA) and peripheral blood eosinophilia. Other laboratory tests that should be consider include FTA-ABS, the Venereal Disease Laboratory Test (VDRL), anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAS-ENAS) in lupus, Epstein-Barr virus titers, ELISA test for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), skin test for anergy, tuberculosis and fungal infections, and nasal cultures for fungi and bacteria.(3,4,5)

In the event all of these tests are negative or if the cause is not clear, a biopsy should be requested before considering surgery. The biopsy sample should be sent to the pathology laboratory and cultured for fungi and mycobacteria.

The biopsy must include the posterior border of the perforation with a generous tissue sample to enable the pathologist to give a final diagnosis and not just report a chronic inflammation. Biopsies including the superior margin must be avoided because they could enlarge the size of the perforation, worsen the humidification pattern, and thus favor the emergence of scabs (4) and compromise the support provided by the nasal dorsum. Septal biopsies do not contribute totally to the diagnosis because the result is often reported as “non-specific” or “non-diagnostic”. (14) Biopsies must be reserved for cases in which there is evidence of bone erosion or a suspicion of malignancy. The sensitivity of biopsies of septal perforations or ulcers done to rule out vasculitis is low; however, when positive, their positive predictive value is high and it may help establish the diagnosis when hematological tests are abnormal. Under other circumstances, biopsies of septal perforations or ulcers may no contribute to clarify the diagnosis and may actually cause unnecessary morbidity. (14)

Pharmacological Medical Management

Medical management of this disease begins with the interruption of the habits that gave rise to the nasal perforation (use of cocaine, inhaled nasal agents, decongestants, digital and/or nasal trauma) and improvement of local hygiene. The routine use of nasal irrigation with saline solution helps reduce scab accumulation and improves humidification of the nasal mucosa. Additionally, the use of a home humidifier may also be of help.

The frequent use of antibiotic or petrolatum-based creams may help prevent dryness and scab formation. In the event there are local signs of mucosal inflammation, twice-daily topical use of antibiotic creams, such as gentamicin, is preferable. It is worth noting that long-term use should not be recommended because it may favor the growth of resistant organisms. (4,5)

The topical use of combined estrogens (Premarin) induces trophic changes of the nasal mucosa (thickening of the nasal mucosa). It is used only in patients with severe epistaxis secondary to septal perforation. The mix is prepared with 25 mg of combined estrogens in 1 bottle of saline solution nasal spray and the patient is instructed to apply two (2) puffs in each nostril twice a day. The mix must be kept refrigerated and disposed of after 30 days. Pediatric use is not recommended and it is important to consider the risks and complications associated with the use of the hormone (hypersensitivity, pregnancy, breastfeeding, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, thromboembolic disorders or liver dysfunction). (5)

Non-pharmacological Medical Management

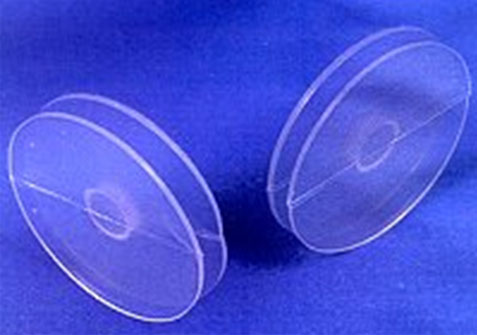

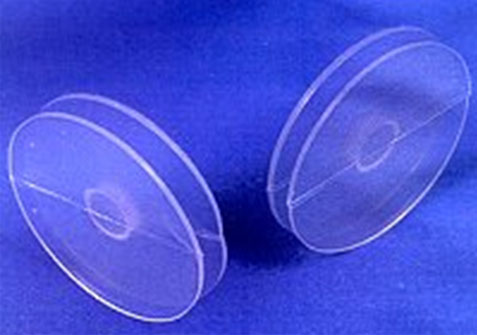

Nasal Septal Button

Temporary closure of the perforation may be proposed using a septal button. The device is placed after the application of a decongestant and a topical anesthetic agent. It consists of 2 silicone disks joined by a central cylinder so that, once it is placed inside the nose, there will be one disk in each nose, joined together through the perforation. Flexible materials are used in order to follow the contours or irregularities of the nasal septum and the perforation.

The button may be left in place for a long time and does not preclude future surgical management. The device provides partial relief of symptoms, but it may produce local irritation, pain, nasal obstruction, accumulation of secretions, and may eventually increase the size of the defect. It is indicated in perforations greater than 3 cm and in patients with contraindications for surgery. It is contraindicated in patients with severe septal deviations (relative contraindication), active local infection, use of intranasal drugs, and active bleeding. (4,5, 17) (Figure 3 )

Surgical Management

Surgical management is an elective procedure for patients who want a resolution of their symptoms. It is contraindicated in active cocaine users. If the specific origin of the perforation has not been clearly identified, or if the edges of the perforation do not seem to be adequately lined, diagnostic testing should be considered before surgery. (6)

Multiple techniques have been described for achieving definitive closure, restoring a normal nasal physiology, and improving the symptoms, but all of them with variable success rates. The fact that there is no agreement regarding the ideal method reflects the drawbacks of each technique. (19) Each surgeon should use the technique with which he or she feels more comfortable and obtains the best results, with as few complications as possible.

Most of the surgical techniques used at present to repair septal perforations are based on 2 basic principles: the use of mucous flaps and the insertion of an interposition element between the two mucosal surfaces.

Flaps that have been described include local rotation or transposition, inferior turbinate, and pedicle/double pedicle advancement flaps. The best results are reported with intranasal mucosa advancement flaps since they contain respiratory epithelium. Others use skin or oral mucosa grafts with good closure results, but with persistent dryness and scab formation due to the characteristics of the epithelium. (3,15,25).

Several interposition materials are used, including cartilage, (nasal septum, ear concha) and bone (mastoid, iliac crest, calvarium and rib). These may create comorbidities at the donor site such as pain, paresthesia, bleeding, infection, non-controlled fractures, pneumothorax or pleural pain, aside from varying degrees of resorption.

Other materials include periostium, temporal fascia, bioactive glass, human acellular allodermal grafts (AlloDerm), titanium membranes and polydioxanone plates. Alloderm, in particular, has become a popular interposition graft because of its availability and ease of use. Titanium membranes as interposition material on the septal defect enable tissue migration – mucosalization – and closure of the defect. Polydioxanone plates are made from resorbable alloplastic with hydrolization characteristics and they are often used in facial trauma and reduction of orbital floor fractures. For the reconstruction of the nasal septum, all the available quadrangular cartilage is removed and then it is cut into pieces and sutured to the plate. Consequently, a composite graft consisting of autologous cartilage and a polydioxanone plate is obtained and then it is reintroduced into the nose to complete the reconstruction. (15,19,20,21,22,25).

Biocompatible fibrin sealants are used to achieve adhesion in separate tissues. They may accelerate scar formation, promote granulation tissue formation and contribute to the regeneration of damaged tissue as a result of the release of several growth factors. This glue is very useful because it prevents graft migration and shortens surgical time, as it reduces the need to use sutures. (16,20,23).

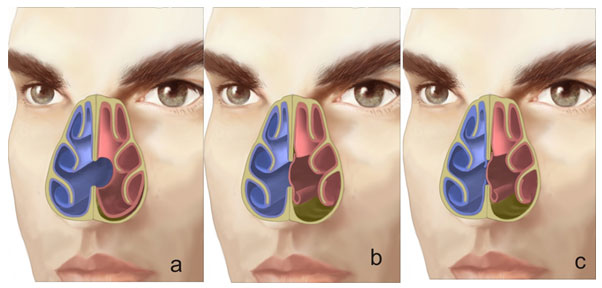

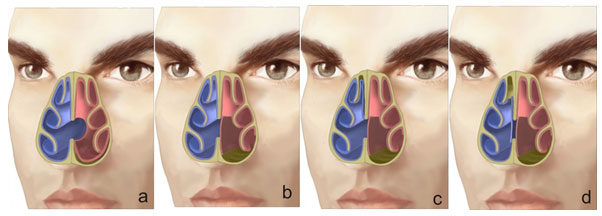

Closure With Mucous Flaps

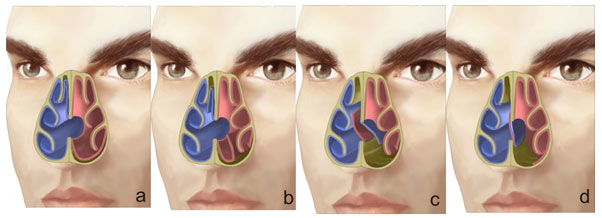

Because of the vasculature of the nasal mucosa, most septal perforations may be repaired using mucosal flaps close to the perforation.(30) (Figs. 4 and 4a)

Use of Upper Flap on one Side and Lower Flap on the Contralateral Side

The procedure begins with a dissection of the lower lateral tunnel that extends up to the insertion of the inferior turbinate where the mucosa is incised in order to allow flap displacement. The flap is displaced cephalad, closing the perforation on that side. The contralateral anterior-superior tunnel is then performed and extended up to the roof of the nasal cavity without using interposition tissue. The incision at the roof allows caudal displacement of the mucosal flap in order to close the perforation. It is also possible to mobilize both mucosal flaps from the floor.

The success of this technique with endoscopic assistance is reported to be higher than 90 %. (17,27) (Figs. 5 and 6)

The mucosa of both nostrils may also be dissected, keeping their insertion on the edge of the perforation. Using a superior incision on one side and an inferior incision of the perforation on the contralateral side, both mucosal layers are dissected in such a way that the flaps cross to the opposite side of the perforation, resulting in full closure. (17,26) (Fig. 7)

Closure Of The Defect Through External Rhinoplasty

Sometimes, the external approach may be useful in closing medium and large perforations where the ability to mobilize the mucoperichonrium and to use both hands may be important success factors.

Inferior Turbinate Pedicle Flap

This technique is useful in perforations of more than 2 cm in size and may be performed endoscopically. The inferior aspect of the turbinate is incised and then a flap incorporating mucosa, submucosa and a variable amount of bone is shaped. The distal portion of the flap is moved anteriorly and sutured for closure of the perforation. A second stage is required three weeks after the initial surgery in order to split the pedicle.

Tunnelized Sublabial Mucosal Flap

This technique is based on a medial pedicle flap that spares the mucosa adjacent to the frenulum when lifted. The flap must be 20% longer than the defect. A sublabial-nasal fistula is then created in order to pass the flap after the septal mucoperichondrium has been elevated. The risk of this procedure is the persistence of the fistula and flap necrosis.

Facial Artery Muscle-mucosal Flap

This flap is useful in perforations 2-4 cm in size. The flap is based on the retrograde flow of the facial artery. The donor area is the oral mucosa immediately underlying the subnasale artery, a subsidiary of the facial artery, and extends to the superior gingivobuccal sulcus. Intra-operative doppler is used to help with the flap design. Once it is dissected, the flap is tunnelized through the subperiosteal dissection at the pyriform aperture. The contralateral side of the perforation may be covered with a skin graft, or allowed to granualate.

Free Radial Flap

The flap is taken from the radial artery and anastomosed to the facial artery. Although it provides fully vascularized dermis, there are issues with the microvascular anastomosis, the length of the operation, morbidity of the donor site and other problems associated with nasal dryness as a result of the skin coverage.

Follow-up

Septal perforations repaired using bilateral flaps have a lower probability of reperforation than those where unilateral flaps are used, regardless of the surgical technique employed. The closure of the perforation under tension may lead to post-operative rupture as a result of contractures formed during normal healing. Another aspect that needs to be considered is the vertical height of the perforation, since it is the most important determining factor for reperforation resulting from the tension between the nasal floor and the dorsum. Because of all of these reasons, the use of interposition grafts and bilateral mucoperichondral flaps is recommended in order to improve the success of the procedure. (15)

Nosebleeds and wheezing may be resolved after successful closure of the perforation, but nasal obstruction and scabs may persist, especially in some cases of large perforations. (15)

Prevention

Prevention of septal perforations is designed to minimize and/or eliminate stress factors. The interventions should focus on patient habits (stop the use of cocaine, stop or minimize the use of nasal vasopressors, recommend the frequent use of nasal humidifiers, avoid digital trauma to the nose, and recommend use of protective gear in work environments where there is a risk of dust, glass or chemical particles) and on health practitioners (avoid large resections on the nasal septum, use surgical techniques that prevent mucosal tears, lubrication of nasogastric tubes before insertion, instruct the patient on the use of nasal corticosteroids).

References

- Oberg D, Akerlund A, Johansson L, et al. Prevalence of nasal septal perforation:

the Skövde population-based study. Rhinology 2003;41(2):72–5. - Topal O, Bilge S, Erbek S, Erbek S. Risk of nasal septal perforation following septoplasty in patients with allergic rhinitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010; DOI 10.1007/s00405-010-13233-y.

- Kridel RWH. Septal perforation repair. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 1999;32:(4):695–724.

- Watson D, Barkdull G. Surgical Management of the Septal Perforation. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 42 (2009) 483–493.

- Batniji R. Septal Perforation-medical Aspects. E-medicine. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/863325-overview Updated Jan 2,2009

- Romo T. Septal Perforation – Surgical Aspects. E-medicine. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/878817-overview Updated sep 10, 2010

- Power D, Kemeny N. Nasal septum perforation and Bevacizumab. Med Oncol 2010. DOI 10.1007/s12032-010-9464-9.

- Traina TA, Norton L, Drucker K, Singh B. Nasal Septum Perforation in a Bevacizumab-Treated Patient with Metastatic Breast Cancer. The Oncologist 2006;11:1070– 1071.

- Zhao K, Dalton P. The way the wind blows: implications of modeling nasal airflow. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2007;7: 117–25.

- Lindemann J, Keck T, Wiesmiller K, Sander B, Brambs HJ, Rettinger G et al. Nasal air temperature and airflow during respiration in numerical simulation based on multi- slice computed tomography scan. Am J Rhinol 2006;20:219–2.

- Kuriloff DB. Nasal septal perforation and nasal obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1989;22:333–350.

- Bhattacharyya N. Clinical Symptomatology and Paranasal Sinus Involvement With Nasal Septal Perforation. Laryngoscope 2007; 117:691-694.

- Lee HP, Garlapati R, Chong VF, Wang DY. Effects of septal perforation on nasal airflow: computer simulation study. J Laryngol Otol 2010; 124, 48–54.

- Diamantopoulos II, Jones NS (2001) The investigation of nasal septal perforations and ulcers. J Laryngol Otol 115:541–544

- Moon IJ, et al. Predictive factors for the outcome of nasal septal perforation repair. Auris Nasus Larynx (2010), doi:10.1016/j.anl.2010.05.006.

- Lee JY, Lee SH, Kim SH, et al. Usefulness of Autologous Cartilage and Fibrin Glue for the Prevention of Septal Perforation during Septal Surgery: A Preliminary Report. Laryngoscope 2006;116, 934-937.

- Tasca I, Compadretti GC. Closure of nasal septal perforation via endonasal approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;135(6):922-7.

- Belachew T. Nasal Septal Button Placement. E-medicine. Available at:http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1580556-overview Updated may 13 2010

- Cogswell LK, Goodacre TE. The management of nasoseptal perforation – REVIEW. Br J Plast Surg 2000;53:117-120.

- Parry JR, Minton Tj, Suryadevara AC, et al. The use of fibrin glue for fixation of acellular human dermal allograft in septal perforation repair. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:417-422.

- Gabory LG, Bareille R, Stoll D. Biphasic calcium phosphate to repair nasal septum: The first in vitro and in vivo study. Acta Biomater 2010;5:909-919.

- Daneshi A, Mohammadi S, Javadi M, Hassannia F. Repair of large nasal septal perforation with titanium membrane Report of 10 cases. Am J Otolaryngol. Jun 23 2009;[Medline].

- Susman E. Fibrin Glue Makes Septal Perforations Easier to Repair. ENToday 2007.

- Lee D, Joseph E, Pontell J, Turk JB. Long-term results of dermal grafting for the repair of nasal septal perforations. Am J Otolaryngol 1999;120:483-486.

- Boenisch M, Nolst Gj. Reconstruction of the Nasal Septum Using Polydioxanone Plate. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2010; 12(1):4-10.

- Dhar V, Watts S. Closure of nasal septum perforation – a novel technique. Clinical Otolaryngology 2009;34: 407–408.

- Presutti L, Ciufelli MA, Marchioni D, et al. Nasal septal perforations: Our surgical technique. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg 2007;136:369-372.

- Pignatari, Nogueira JF, Stamm AC. Endoscopic “crossover flap” technique for nasal septal perforations. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg 2010;142:132-134.

- Sclafani A. Repair of large nasal septal perforations via the external rhinoplasty approach. Op Tech Otolaryngol—H&N SURG, 2001;12:20-24.

- Pedroza.F, Gomes L., Arevalo O. A Review of 25-Year Experience of Nasal Septal Perforation Repair. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:12-1

Septal Perforation Graphs

The scale indicates the color code from lower (blue) to higher (red) velocity. (Taken from “Effects of septal perforation on nasal airflow: computer simulation study”) (13)