Nasal septal perforations can be problematic to patients and challenging to surgeons. The perforated nasal septum often has obliterated surgical tissue planes that may be difficult to dissect. Although the literature suggests numerous techniques for management and repair, a more limited number of techniques have achieved widespread favor. In this chapter, we provide an overview of the anatomy, pathophysiology, and evaluation of nasal septal perforations and describe the general principles behind the more commonly used repair techniques.

A similar problem faced by the revision surgeon is a previously operated septum with persisting deviation. As with septal perforations, obliterated surgical planes can complicate the surgical management of this problem. Endoscopic techniques are extremely beneficial in this cir- cumstance, and they are described in this chapter.

Anatomy of the Nasal Septum

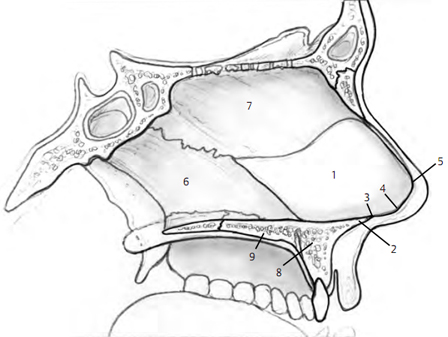

The nasal septum has a posterior bony portion and an anterior cartilaginous portion terminating in connective tissue (Fig. 5–1). The bony portion consists of the perpen- dicular plate of the ethmoid bone superiorly and the vomer inferiorly. The cartilaginous portion extends to the nasal vestibule. The anterior-most septum, or caudal sep- tum, is attached to the medial crura by connective tissue. This connection constitutes a major tip support mecha- nism. Septal cartilage is approximately 2 mm thick superi- orly and 4 mm thick inferiorly. 1, 2

The anterior ethmoid artery arises from the ophthalmic artery, passes through the cribriform plate from the ante- rior cranial fossa to the roof of the nasal cavity, and divides into anterior septal branches and anterolateral nasal branches. Branches from the anterior ethmoid artery pro- vide vascular supply to the anterior and superior septum. The posterior ethmoid artery has branches that supply the posterior and superior portion of the septum. The sphenopalatine artery arises from the maxillary artery in the pterygopalatine fossa and passes through the sphenopalatine foramen to enter the nasal cavity from below. It divides into posterior septal branches and pos- terolateral nasal branches. An anterior branch of the sphenopalatine artery runs typically just below the middle of the septum to anastomose with a vascular network known as Kiesselbach’s plexus. This plexus also consists of branches of the anterior ethmoid artery, the superior labial artery, and a nasopalatine branch of the lesser palatine artery that enters through the incisive canal. 1, 2

Etiology

Septal cartilage depends on its overlying mucous mem- brane for blood supply. When this membrane is injured in corresponding areas bilaterally, the septum is devascular- ized. Although some causes of mucosal and septal injury are easily recognized, others will not have a readily identi- fiable underlying disease process. A thorough evaluation may lead to the identification of one of the potential etiologies of nasal septal perforations listed in Table 5–1. 1

The most frequently recognized cause of nasal septal perforation is iatrogenic and is associated with nasal sur- gery and nasal procedures. 3,4 Tight nasal packs and elec- trocautery can impair the mucoperichondrial blood supply or damage the mucosal membranes of the nasal septum directly. Direct injury from surgical intervention, including septoplasty, rhinoplasty, endoscopic sinus sur- gery, and cryotherapy are recognized as frequent causes of nasal septal injury.

Mechanical or chemical irritation of the septal mucosa may lead to septal perforation, especially if the irritation is chronic. Chronic decongestant nasal spray and cocaine use cause direct vascular impairment through their vasocon- strictive effects. Cocaine also tends to be mixed with other substances that are irritating to the nasal mucosa. Mucosal irritation and impaired blood supply predispose to infec- tion, which complicates the disease process and con- tributes to septal perforation and additional bone and structural tissue loss. Chronic use of certain nasal steroid sprays also has been associated with septal perforation. With regard to mechanical causes, habitual nose pick- ing may cause bleeding, crusting, and ulceration, with sec- ondary impairment of blood supply, ischemia of cartilage, and perforation. Foreign bodies inserted in the nose also may cause septal perforation by similar mechanism. The damaging effects of any irritant are compounded by ciga- rette smoke. 1, 3

Traumatic injury to the nose with septal mucosal injury or untreated septal hematoma can lead to fibrosis, infec- tion, abscess, and resultant perforation. All patients suffer- ing nasal injury and possible fracture therefore should undergo a careful examination, including rhinoscopy, to evaluate for the possibility of injury to the septum.

Table 5-1 Causes of Nasal Septal Perforation

| Infectious/Inflammatory | Drugs/Irritants | Trauma/Injury | Neoplastic |

| Tuberculosis Syphilis Typhoid Diphtheria Fungal Wegener’s granulomatosis Collagen vascular disease Sarcoidosis Vasculitides | Vasoconstrictive inhalants Cocaine Cigarette smoke Chromic/sulfuric acid fumes Chemical/industrial dusts Lime Salt Heavy metals Arsenicals/cyanide | Nasal/septal surgery Hematoma Nose picking Foreign bodies Fracture/piercing Cautery for epistaxis Cryosurgery Packing/suctioning Nasotracheal intubation | Squamous cell carcinoma Adenocarcinoma Leukemia Metastatic carcinoma Midline granuloma |

Patient Evaluation

Clinical Presentation

| Crusting Epistaxis Difficulty breathing Whistling Localized pain Rhinorrhea Headache | Postnasal drip Hyposmia/anosmia Dry nose Dry mouth Voice changes Foul odor Aesthetic deformity |

Approximately two thirds of nasal septal perforations are asymptomatic; thus, many are discovered incidentally. 5 More anteriorly located perforations are more likely to be symptomatic. Table 5–2 lists the common presenting symptoms of patients with nasal septal perforation.

Crusting, bleeding, and difficulty breathing are the main symptoms associated with larger perforations, whereas whistling tends to be more frequently associated with smaller perforations. 6 Crusting occurs after desicca- tion of the nasal mucosa due to replacement of normal laminar inspiratory air currents by turbulent air currents and lower air humidification. 3 Persistent irritation and low-grade inflammation impair the healing process over the exposed cartilage and lead to bleeding. Dried blood and crusting obstruct the nasal airway and can make breathing difficult. Pain is usually a result of the localized inflammatory process.

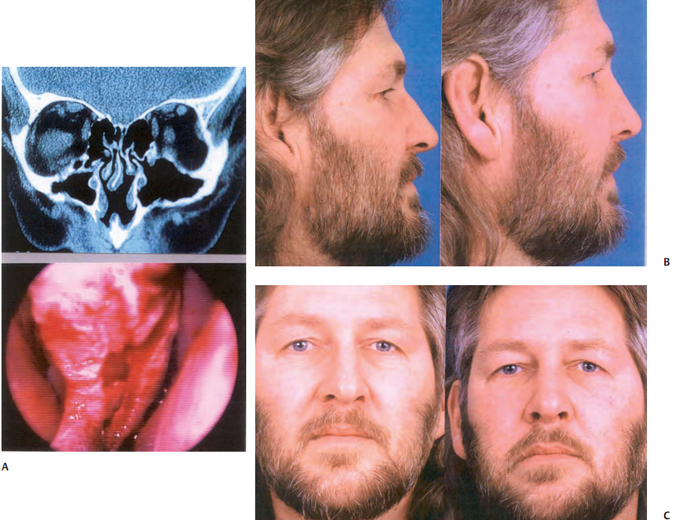

Patients with septal perforation may also present with a cosmetic deformity, specifically with a saddle nose. This deformity may vary in severity from the mildest saddling to severe saddle nose with total nasal collapse (Fig. 5–2).

Posterior perforations are usually less symptomatic because of rapid air humidification by the anterior nasal mucosal lining. Therefore, these perforations often cause no debility and typically do not require repair.

History and Physical Examination

It is important to obtain a thorough history of the patient presenting with septal perforation to establish an etiology, if possible, before reparative surgery. The patient should be questioned about a history of acute or chronic nasal disease, any previous history of systemic disease, previ- ous nasal instrumentation or surgery, a history of facial trauma or habitual nose picking, use of prescribed and nonprescribed medications or nasal sprays, use of any illicit drugs, hazardous occupational exposures, and exposure to first- or second-hand cigarette smoke. Active infectious, inflammatory or systemic disease, or cocaine abuse within 6 months of presentation should preclude reparative surgery until infection is eradicated, inflammation is controlled, and the patient has had adequate time and support for appropriate behavioral modification. 6,7

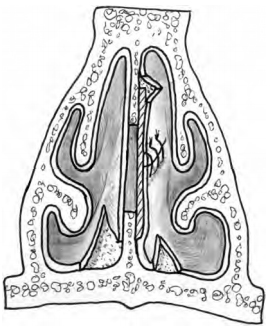

The physical examination likewise should contribute to establishing an etiology. All patients should have a thor- ough head and neck evaluation. Removal of nasal crusts and decongestion of the nasal mucosa helps the surgeon visualize the entire nasal septum. Appropriate visualiza- tion with nasal endoscopes makes it easier to see small and posterior perforations. The location and size of the perforation should be noted and recorded, and attention should be paid to the edges of the perforation and the shape of the mucosa and cartilage immediately surround- ing it. The presence of inflamed and crusted mucosal edges suggests an unfavorable local environment that must be addressed before any planned repair.

The surgeon should evaluate for other causes of nasal obstruction, such as sinusitis or persistent septal deviation (Fig. 5–3). If the surgeon simply assumes that a patient’s nasal obstruction is because of an existing perforation, then another cause of the patient’s obstruction may be overlooked, and the patient may have persisting symp- toms despite surgical intervention.

Concomitant external collapse of the nose may occur with a large septal perforation when this results in loss of structural nasal support (Fig. 5–2).

Unless the history and physical examination establish a clear etiology, additional work-up should ensue. The anti- neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody test, antiphospholipid, and Epstein-Barr Virus titers; nasal bacterial and fungal cultures; the purified protein derivative skin test for tuberculin; and the venereal disease research laboratory test may collectively help establish a diagnosis. Biopsies of any granulation tissue should be performed for pathologic evaluation and to rule out a neoplastic or active inflamma- tory process. Biopsies should be performed in the poste- rior direction, when possible, to decrease the vertical height of the perforation and to minimize anterior exten- sion of the perforation with worsening of symptoms. 3 It is also important to biopsy a sample of tissue extending away from the inflamed edge of the perforation so that the pathologist has adequate tissue to make a potential diag- nosis. Patients with suspected granulomatous disease should have a computed tomography (CT) scan of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Asymptomatic patients rarely require treatment. Patients with mild symptoms, usually consisting of crusting and dryness, often benefit from frequent nasal irrigations with normal saline solution, sometimes with the addition of ointments and emollients (e.g., mupirocin and others). The addition of a mildly acidic substance to the irrigation solu- tion (e.g., vinegar, boric acid powder) helps reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus colo- nization of the crusty nose. 4

For symptomatic nonoperative candidates, a medical- grade Silastic (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) prosthesis may be of benefit. These come in prefabricated sizes or can be made by a prosthetist if given measured dimensions. Prosthesis insertion is more likely to be successful if it is trimmed to fit comfortably and without applied pressure to the nasal cartilages or nasal floor. A better fit is main- tained when the portions of septum anterior and posterior to the perforation are straight.

Patients may be considered to be nonoperative candi- dates if their health precludes general anesthesia, if they have an active granulomatous or collagen vascular disease, or if they have a history of ongoing intranasal medication use such as over-the-counter nasal decongestant sprays or cocaine. Even with successful repair of a septal perforation in this setting, disease recurrence can lead to reperforation. 3

Aside from their usefulness in the nonoperative patient, prosthesis procedures can be cost-effective and do not afford the operative risks of reparative surgery for the mildly symptomatic patient. They are not universally tol- erated or successful, however, and do require continued follow-up care indefinitely.

Surgical Treatment

The potential complexity presented by surgical treatment of septal perforations is highlighted by the existence of abundant proposed techniques for repair in the literature. Although septal perforations occur in different shapes, sizes, and locations, certain principles should be considered by the surgeon when addressing the operative repair of any septal perforation.

The majority of perforations are asymptomatic; only those that are symptomatic and refractory to conservative management should be operated on. Surgery should be performed only after the etiology is reasonably established and underlying disease is controlled, because perforation repair in the face of an active inflammatory process frequently fails because of compromised blood supply and host bed scarring. Ongoing substance abuse, as well as active inflammatory diseases (e.g., Wegener’s), are absolute contraindications to surgical intervention.

Ideal preoperative preparation of the septal mucosa takes 2 or more weeks and requires significant nasal care from the patient. Sterile saline irrigations of the nasal cavity should be performed two to four times daily; application of ointments and emollients help to alleviate crusting in the weeks before surgery. If necessary and if practical, the patient may be seen weekly before surgery to assist with nasal hygiene. Any infection should be completely eradicated before surgery. 3

Before initiating surgery, diagnostic nasal endoscopy is recommended. Photographic documentation of the perforation also may be beneficial.

Advantages of Endoscopic Revision Septoplasty

If septal deviation persists posteriorly after a septoplasty, persisting nasal obstruction may require revision septoplasty. Because the mucosal flaps are often densely adher- ent after a septoplasty, revision septoplasty involving a traditional approach may present technical difficulty, including significant risk of septal perforation.

Endoscopic septoplasty is a relatively recent and important technique that has direct application in this situation. The endoscopic approach may be a useful adjunct in these difficult revision cases in which a complete elevation of the mucoperichondrial flap presents difficulties, such as persistent posterior septal obstruction after prior septoplasty or prior septal injury (such as hematoma or abscess) with loss of cartilaginous septum. In these cases, typical surgical dissection planes are obliterated and complete elevation of the mucoperichondrial or mucoperiosteal flaps may be difficult. The ability to address a persisting deviation, elevat- ing the mucosal flap directly over the offending deviation using endoscopic techniques greatly facilitates treatment.

Most rhinologic (i.e., sinus) surgeons are familiar with the benefits of diagnostic endoscopy and endoscopic surgical techniques in the context of sinus and nasal dysfunction. However, these advantages may not be as widely recognized in the rhinoplasty community. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy and endoscopic techniques, including endoscopic septoplasty, are important tools in the rhino- plasty surgeon’s armamentarium.

Endoscopic septoplasty is a well-described technique for correction of septal deformities. 8–14 First described in 1991, 8 its use has been reported for the treatment of iso- lated septal spurs9–12 and in the treatment of more broad- based septal deformities. 13 Advantages of the endoscopic technique include potentially improved visualization of posterior septal deformities, the opportunity for limited minimally invasive procedures, and potential improved access in certain revision cases.

Endoscopic septoplasty offers distinctive advantages in selected difficult cases of revision septoplasty and septal perforation repair. 14,15 Although septoplasty and septal perforation repair do not commonly require endoscopic approaches, the endoscopic approach may be a useful adjunct in difficult revision cases in which complete elevation of a mucoperichondrial flap presents difficulties. Examples include a persistent posterior septal obstruction after prior septoplasty or after septal injury (such as hematoma or abscess) with loss of cartilaginous septum. In these cases, typical surgical dissection planes are obliterated, and complete elevation of a mucoperichondrial or mucoperiosteal flap may be difficult. The ability to directly address a persisting deviation, elevating the mucosal flap directly over the offending deviation using endoscopic techniques, greatly facilitates treatment.

The technique of endoscopic septoplasty has been well described. 8–14 For a broadly based septal deviation, a standard Killian or hemitransfixion incision may be made. For an iso- lated posterior deformity, the incision may be positioned in the immediate vicinity of the deformity. Mucoperichondrial and mucoperiosteal flap elevation is facilitated by a suction elevator. For a broad-based deviation, the septal cartilage may be incised, and the contralateral mucoperichondrial and mucoperiosteal flaps are elevated, taking great care to preserve a generous L-strut of at least 15 mm for continued nasal support. If an isolated posterior deformity is addressed, the cartilage or bone is incised several millimeters posterior to the mucosal incision and the contralateral mucosal flap is elevated. Deviated portions of septal cartilage and bone are corrected or removed. Straightened or morselized cartilage may be replaced, and the septal flaps may be closed with a quilting suture, although in more limited cases, suturing may not be necessary

Principles of Septal Perforation Repair

The surgical approach to perforation repair should be tai- lored to the size and location of the perforation. The approach selected should optimize exposure and visuali- zation, while at the same time minimizing the number and extent of incisions.

Regardless of the approach, all repairs of septal perfora- tions share certain principles. Local anesthesia injected about the mucosa of the perforation not only provides hemostasis and local anesthesia, but it also provides some hydrodissection that facilitates the potentially difficult dissection around the septal perforation. With regard to the perforation, the surgeon must be prepared to encounter a cartilaginous or bony septal defect larger than the perforation itself. This is important because where septal cartilage or bone is absent, the mucosal flaps will be densely adherent, and dissection will be difficult.

Regardless of the approach or the size of the perforation, a key principle is to elevate the mucosal flaps atraumatically, and then to advance the flaps in such a manner that they can be sutured closed. Also, experience has shown that interposition of material between the flaps improves the long-term success of the closure. 4

Surgical Approaches and Graft Selection

In this section, we will first discuss the surgical approaches available, then we will address the ways to advance the mucosa and close the septal perforation. Finally, we will discuss the various interposition graft materials available to the surgeon.

Surgical Approaches

Intranasal Approach

Small perforations (i.e., less than 0.5 cm) can often be repaired through a closed intranasal approach. 4 The intranasal approach is perhaps the most widely used approach, because of the greater proportion of small per- forations. However, the surgeon should keep in mind that limited exposure and visualization make repair of larger and more posterior perforations more difficult using this approach.

External Rhinoplasty Approach

Repair of larger (i.e., 0.5–3.0 cm) and posterior perforations may be facilitated by the added exposure afforded by extranasal incisions. Although lateral alotomy is well described in the literature, the external rhinoplasty approach appears to have replaced the lateral alotomy as the approach of choice for these perforations, because the external rhino- plasty approach affords equal or better exposure to the nasal cavity bilaterally, and results in better cosmesis. 4,16,17

To address the septal perforation, the upper lateral car- tilages are separated from the septum intranasally, and lateral retraction allows increased exposure and access to the septal perforation. 3 Dissection of the septal mucosa may proceed both from above and through an intranasal approach, facilitating the dissection.

The external rhinoplasty technique allows increased exposure, a bimanual approach, and binocular visualiza- tion of larger and posteriorly based septal perforations, all of which increase the likelihood of successful repair. However, care must be taken to reconstitute the support mechanisms violated in the course of the repair. Specifically, the upper lateral cartilages must be reat- tached to the dorsal septum. In addition, the medial crura must be secured if they are dissected apart in the course of surgery; the surgeon should strongly consider placing a columellar strut between the medial crura for additional tip support. 2,3

Other Approaches

A midfacial degloving approach has been described for very large perforations (i.e., greater than 3.0 cm) repaired through two-stage transposition of posteriorly based expanded mucosal flaps. 7 As with the open rhinoplasty approach, this approach maximizes exposure and visuali- zation but has the disadvantage of disrupting the blood supply to the nasal septum coming from the anterior nasal floor.

Closure of Perforation

Septal Mucoperichondrial Advancement-Rotation Flaps

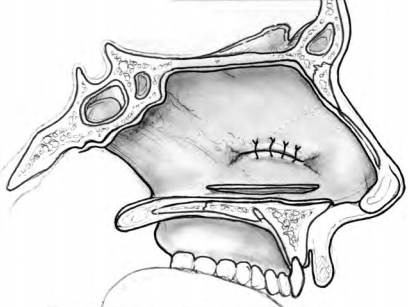

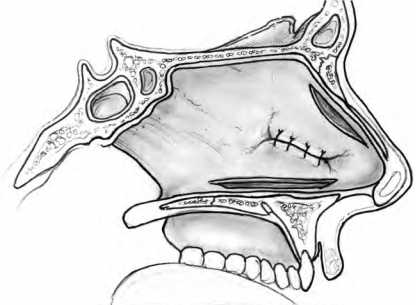

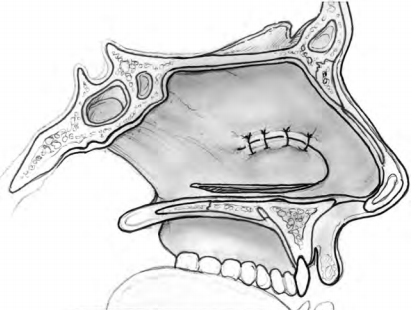

Intranasal advancement flaps are ideal for repair because they can close the septal perforation without compromis- ing normal intranasal respiratory epithelium and physiol- ogy. Generally, these flaps should be broadly based and designed in such a way as to use, and not transect, branches of the anterior ethmoid and sphenopalatine arteries. A flap attached anteriorly and posteriorly is a bipedicled flap with blood supply from both directions. These can be inferior flaps (Fig. 5–4) or may be combined with a superior bipedicle flap for increased mucoperi- chondrial mobilization and closure of larger perforations (Fig. 5–5). When the incision for an inferior bipedicled advancement flap does not adequately mobilize enough mucoperichondrium for advancement, the incision can be extended medially in line with the anterior aspect of the perforation. These flaps are called rotation flaps and are unipedicled with unidirectional vascular supply (Fig. 5–6). Depending on the location of the perforation, the single incision advancement and rotation flaps can be based superiorly as well. Whichever design is used for the mucosal flaps, the repair should involve placement of an interposition graft.

The superior flap is created from an incision just ventral to the nasal dorsum and is usually easy to advance. The inferior releasing incision is made along the nasal floor, at least 1 to 2 cm behind the posterior edge of the perforation, and can be curved out beneath the inferior turbinate if additional mucosa is needed. The size of the flaps should be planned so that there is minimal tension on the free edges. The perforation is carefully closed with approximating interrupted 4–0 or 5–0 chromic or plain gut sutures.

It is useful but not essential to raise another flap on the contralateral side if the perforation is completely closed by advancement or rotation of mucoperichondrium on the first side. Bilateral flap closure accelerates healing time and is generally recommended. Only a lower flap should be raised on the contralateral side, however, because a superior advancement flap would expose cartilage bilaterally, predisposing to a new perforation.

1 Contralateral flaps should be designed to cover any cartilage not covered by mucoperichondrium on the other side, while not exposing cartilage on both sides.

Tissue Expansion

The size of any septal perforation is inversely proportional to the amount of mucoperichondrium available for flap advancement. Thus, for large perforations of at least 3 cm, a two-stage procedure involving mucosal tissue expansion has been described. 18 The first stage consists of bilateral insertion of tissue expanders under the nasal floor mucosa. An incision is made from the anterior nasal sill laterally onto the pyriform aperture. Submucoperiosteal elevation of the nasal floor with a curved Cottle elevator extends from the anterior bony pyriform edge posteriorly to the insertion of the hard and soft palate. Horizontal dis- section extends from the medial maxillary crest to the intersection of the bony nasal floor and lateral nasal wall. The tissue expander is inserted into this submucoperiosteal pocket.

A pocket for the remote port is created on the frontal process of the maxillary bone or in the canine fossa inferior to the infraorbital nerve. The incision is closed with 4–0 chromic sutures and tissue expansion is performed weekly with 0.5 to 1.0 mL of sterile saline injections. Expansion typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks and requires on the order of 4 to 7 mL of expander volume. 18

After adequate tissue expansion, the second stage of the procedure begins with midfacial degloving and removal of the tissue expanders bilaterally. Posteriorly based mucosal flaps are raised to close the perforation with an interposition graft placed. A skin graft is sometimes used to cover the nasal floor, and packing is placed. Tissue expansion allows for closure of large perforations with local epithelial advancement and restoration of normal nasal physiology. It has been reported that a gain of 5 cm of flap length can be expected with the use of 1 × 3 cm tissue expanders. 7

Sublabial Mucosal Flap

This repair technique consists of an anteriorly based mucosal flap pedicled on the labial artery and positioned through a sublabial approach. It is appropriate mostly for long perforations positioned anteriorly. A medially based flap just lateral to the midline frenulum is created with sharp dissection beneath the upper lip and along the buccal mucosa. The flap should be sized to overlap the perforation to allow for tension-free closure. The sur- geon also must be careful not to injure Stenson’s duct. The raw mucosal defect is partially closed without tension using 5–0 chromic sutures, and hemostasis is afforded by microcautery.

Creation of a midline sublabial–nasal fistula follows from the superior border of the flap base to the floor of the nose adjacent to the perforation. When this fistula is made too small (i.e., < 1.0 cm), early closure of the tract can occur leading to flap strangulation. The flap is guided through the fistula, positioned with edges beneath the elevated mucoperichondrium, and sutured about the perforation carefully. The opposite surface of the flap is dressed with Gelfoam (Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) or similar material, and the nose is lightly packed with antibiotic-impregnated bandages. 1

Free Flap

The technique of free flap repair has been used for the clo- sure of larger septal perforations with inadequate intranasal mucosa available for advancement. A small Penrose drain is usually left in each nasal cavity for one week to prevent synechiae. Intermaxillary fixation for 2 weeks is also needed to minimize trauma to the pedicle from movement of the mandible. 5 This technique offers the advantage of using a large amount of thin, pliable, highly vascular tissue available for closure of large septal perforations. Microvascular anastomosis is required, however, and an extended inpatient hospital course can be expected. It is the rare patient that would be a candidate for this approach.

Interposition Graft Selection

Independent of the surgical technique planned for perfo- ration repair, the repair should involve placement of some interposition graft. The graft acts as a barrier to incisional breakdown and reperforation, as well as a scaffold for overgrowth of new mucosal membrane. Because the use of interposition grafts has gained widespread acceptance, a variety of materials have been used. Whatever the mate- rial used, however, the graft should have the capacity to survive a prolonged period of poor blood supply with low metabolic requirements, should be relatively thin, should not elicit an immune response, should be obtainable with minimal risk to the patient, and should act as a template for overlying tissue migration.

Connective tissue autografts have been the most com- monly used interposition grafts and typically consist of temporalis fascia or cranial periosteum. These grafts are extremely thin and act as an excellent structural frame- work for the overgrowth of new fibroblasts. 20 The graft is typically harvested through an incision above and behind the ear. When the temporalis fascia is too thin, the dissec- tion may proceed through the temporalis muscle to the cranial periosteum. The amount of tissue harvested should generally be approximately 2 cm larger in diameter than the perforation it is intended to cover. The tissue should be allowed to dry before its placement as a graft.

Some practitioners have maintained that temporalis fascia autografts are too thin to afford adequate solidity and support for regenerating mucosa6 and that rehydrated fascia loses its gross structural stability and becomes tech- nically difficult to manage. 21 Tragal cartilage, 22 conchal car- tilage, 6 rib cartilage, 23 and a modified temporoparietal fascia/tragal cartilage/deep temporal fascia sandwich grafts24 have been described as cartilage-based interposi- tion graft alternatives.

Still other surgeons have suggested that for larger per- forations, tragal cartilage grafts may be too small and con- chal cartilage too difficult to flatten when needed in large pieces. 25 When greater strength is needed, use of bone grafts has been described as an alternative to cartilage- based grafts. Common bone grafts include the perpendicu- lar plate of the ethmoid (PPE) and the mastoid cortex. 25 If enough PPE is available to cover the perforation, the authors consider it to be the bone graft of choice. Bone grafts afford great structural stability and have a high resistance to necrosis and reperforation. As with cartilage grafts, though, they should be combined with some mucosal flap or thin connective tissue autograft to maxi- mize epithelialization and successful repair.

Some authors have described the use of dermis as an interposition autograft, 26 whereas others have advocated repair with acellular human dermal allografts [AlloDerm (LifeCell Corporation, Branchburg, NJ). 7, 21 Dermal autografts can be harvested from the inner upper arm or lateral thigh. A dermatome is used to first lift the epidermis (0.2 mm in thickness). The dermal graft of equal length and thickness is then harvested, and the epidermis replaced and sutured. 26

The advantages of acellular human dermal allografts include lack of donor site morbidity, availability in large sizes sufficient for large perforation repair, and decreased operative time. Allograft processing is designed to strip all cellular components from the dermal layer, thereby mini- mizing risk of a host immune response and transmission of infection (Fig. 5–7).

Postoperative Care

Depending on the repair technique, the postoperative course can vary somewhat significantly. Generally, how- ever, patients should be assured that light bloody dis- charge over the first 24 hours should be anticipated and should not cause alarm. Intranasal packing is removed on postoperative day one. Intranasal splints, such as Doyle or Reuter splints, when placed are typically removed after approximately one week. If Gelfoam or other absorbablepacking is placed along the septum, saline drops four times daily keep the Gelfoam moist and facilitates its timely dissolution. Postoperative crusting is minimized with cotton-tip application of antibacterial ointment 3 to 4 times daily.

Columellar sutures are removed between postoperative days 5 and 7. The patient is advised to refrain from exposure to cigarette smoke, vasoconstrictive sprays, and blowing of the nose during at least the first postoperative month. The patient is seen weekly for suctioning, wound care, and observation. Photographic documentation may be helpful.

Outcomes

The modern literature on septal perforation repair supports a graduated approach to repair based on perforation size and location. The literature today suggests that properly selected symptomatic septal perforations may be closed with a high degree of reliability. One series involving more than100 bipedicled advancement flaps with connective tissue autografts reports a success rate of 95% complete closure of perforations up to 3 cm in diameter with 1 to 24 years follow-up. 4 Another series demonstrated a 93% clo- sure rate of perforations 0.5 to 2.0 cm using an extended rhinoplasty approach with bilateral posteriorly based mucosal flaps and an 82% closure rate of perforations 2.0 to 4.5 cm using a two-staged midfacial degloving approach with medial advancement of posteriorly based expanded mucosal flaps. 7 Even with unsuccessful complete closure, perforations are usually made smaller.

Summary

Nasal septal perforation is a relatively common problem that can be distinctly challenging to the surgeon. There are many etiologies, and the patient may be entirely asympto- matic, or symptoms can become bothersome across a spectrum of severity. Thorough physical examination and investigation into the etiology are imperative before initi- ation of any management plan.

When surgery is necessary, the surgeon should be com- fortable with the more common techniques. Adherence to the general principles of repair and application of meticu- lous surgical technique increase the chance of successful repair.

References

- Fairbank DN, Fairbanks GR. Nasal septal perforation: prevention and management. Ann Plast Surg 1980;5:452–459

- Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: 1999

- Kridel RWH. Septal perforation repair. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32:695–724

- Fairbanks DNF. Nasal septal perforation repair: 25-year experience with the flap and graft technique. The American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery 1994;11:189–194

- Murrell GL, Karakla DW, Messa A. Free flap repair of septal perfo- ration. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102:818–821

- Woolford TJ, Jones NS. Repair of nasal septal perforations using local mucosal flaps and a composite cartilage graft. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115:22–25

- Romo T III, Sclafani AP, Falk AN, et al. A graduated approach to the repair of nasal septal perforations. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;103: 66–75

- Lanza DC, Kennedy DW, Zinreich SJ. Nasal endoscopy and its surgi- cal applications. In: Lee KJ, ed. Essential Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. New York, NY: Medical Examination Publishing Co., 1991:373–387

- Lanza DC, Rosin DF, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic septal spur resec- tion. Am J Rhinol 1993;7:213–216

- Cantrell H. Limited septoplasty for endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;116:274–277

- Giles WC, Gross CW, Abram AC, et al. Endoscopic septoplasty. Laryngoscope 1994;104:1507–1509

- Hwang PH, McLaughlin RB, Lanza DC, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic septoplasty: indications, technique, and results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:678–682

- Stamberger H. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: The Messerklinger technique. Philadelphia, PA: BC Decker, 1991:432–433.

- Becker DG, Kallman J. Endoscopic septoplasty in functional sep- torhinoplasty. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery 2000;10:25–30

- Becker DG. Septoplasty and Turbinate Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2003;23:393–403

- Goodman WS, Strezlow VV. The surgical closure of nasal septal perforations. Laryngoscope 1982;92:121–124

- Kridel RWH, Appling WD, Wright WK. Septal perforation closure utilizing the external septorhinoplasty approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1986;112:168–172

- Romo T III, Jablonski RD, Shapiro AL, et al. Long-term nasal mucosal tissue expansion use in repair of large nasoseptal perfora- tions. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121:327–331

- Tardy ME Jr. Sublabial mucosal flap: repair of septal perforations. Laryngoscope 1977;87:275–278

- Patterson ME, Lockwood RW, Sheehy JL. Temporalis fascia in tym- panic membrane grafting. Arch Otolaryngol 1967;85:287–291

- Kridel RW, Foda H, Lunde KC. Septal perforation repair with acellular dermal allograft. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:73–78

- Hussain A, Kay N. Tragal cartilage inferior turbinate mucope- riosteal sandwich graft technique for repair of nasal septal perfo- rations. J Laryngol Otol 1992;106:893–895

- Schultz-Coulon HJ. Experiences with the bridge-flap technique for the repair of large nasal septal perforations. Rhinology 1994;32: 25–33

- Hussain A, Murthy P. Modified tragal cartilage – temporoparietal and deep temporal fascia sandwich graft technique for repair of nasal septal perforations. J Laryngol Otol 1997;111:435–437

- Nunez-Fernandez D, Vokurka J, Chrobok V. Bone and temporal fas- cia graft for the closure of septal perforation. J Laryngol Otol 1998;112:1167–1171

- Lee D, Joseph EM, Pontell J, et al. Long-term results of dermal grafting for the repair of nasal perforations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:483–486