Abstract

Correction of the severely twisted nose is one of the greatest challenges in septorhinoplasty. Both functional and aesthetic problems arise, and standard septoplasty and/or rhinoplasty techniques are rarely successful for such severe deviations’. We describe our technique for extracorporeal septoplasty, which may or may not be combined with rhinoplasty techniques. We use polydioxanone foil, an absorbable material, to support the reconstructed septal cartilage, and discuss the evidence for its use.

Introduction

Severe deviation is often the result of birth or childhood trauma, with subsequent abnormal growth leading to the so-called “congenital” twisted nose.1 Lesions of or trauma to the septal cartilages can disturb the growth of the whole nose, middle third of the face and maxilla, as shown in studies of identical twins.2,3 Significant trauma in later life can also lead to a twisted nose, and more rarely it occurs as a postoperative complication following rhinoplasty. Patients complain of both cosmetic and functional issues as a result of this nasal deformity, which requires careful preoperative evaluation and surgical planning.

When assessing the nose preoperatively, it should be divided as usual into thirds. The upper bony third may or may not be deviated. The most difficult aspect of the twisted nose is correction of a deviated middle third; this is when extracorporeal septoplasty must be considered, as without it the deformity is likely to recur. Any deviation of the lower third may be related to a mid-third deformity. The tip itself may be symmetrical, if away from the midline, or may need separate consideration.

The septum itself should be assessed by anterior rhinoscopy as well as rigid endoscopy of the nose, to evaluate the septum along its whole length. Multiple fracture lines are often found and, with or without middle third twisting, are the commonest indication for this procedure in the authors’ experience. In the twisted nose, the septum is often significantly deviated in the same direction as the external nose, sometimes in a “C” and sometimes in an “S” shape.

Septal Anatomy

The septum is formed from bone and cartilage. The bony septum is formed posterosuperiorly by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, posteroinferiorly by the vomer and palatine bone, and inferiorly by the maxillary crest. Anteriorly the septum is formed mainly by the quadrilateral cartilage, which is continuous with the upper lateral cartilages of the nose superiorly. The caudal end of the quadrilateral cartilage is attached to the membranous septum, which is further supported by the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilage on each side.4

Extracorporeal Septoplasty Technique

Our technique for extracorporeal septoplasty requires complete separation of the quadrilateral cartilage from all its attachments, so that it can be removed from the nose for reshaping. We do not routinely remove any bony septum, although this has been described previously.5,6 Whilst extracorporeal septoplasty can be performed through an endonasal approach, it more often requires an external rhinoplasty approach for full exposure; this also allows any tip work necessary to be easily performed.

Following routine preparation of the nose, local anaesthetic (lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:80,000) is injected into both sides of the septum, the alar margins and columella. This should be continued subcutaneously over the dorsum of the nose as is routinely done for rhinoplasty. An inverted “v” transcolumellar incision is made, and the columellar skin elevated off the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages. Bilateral marginal incisions are continued and the dorsal skin and soft tissue envelope elevated as in any external rhinoplasty approach. The soft tissue between the medial crura, membranous septum and interdomal ligaments is divided to approach the caudal septum. The anterior septal angle should then be identified, and the subperichondrial plane found. Mucoperichondrial flaps are then elevated bilaterally, and continued posteriorly along the length of the cartilaginous and bony septum, as well as inferiorly (as mucoperiostial flaps) over the maxillary crest. Once the quadrilateral cartilage is fully exposed, it must be separated from the bony septum posteriorly and the maxillary crest and anterior nasal spine inferiorly. A scalpel should be used to detach it from the upper lateral cartilages. The attachment at the keystone area requires special attention as the cartilage usually extends posterior to the nasal bones. Sharp dissection with a scalpel or strong scissors is required just posterior to the nasal bones to completely free the septum. Once this has been done it can be easily removed from the nose.

It is important to retain the original orientation of the cartilage once it is outside the nose, to ensure that the correct shape and support is retained when it is reinserted. This can be done simply by marking the caudal end at its attachment to the anterior nasal spine.

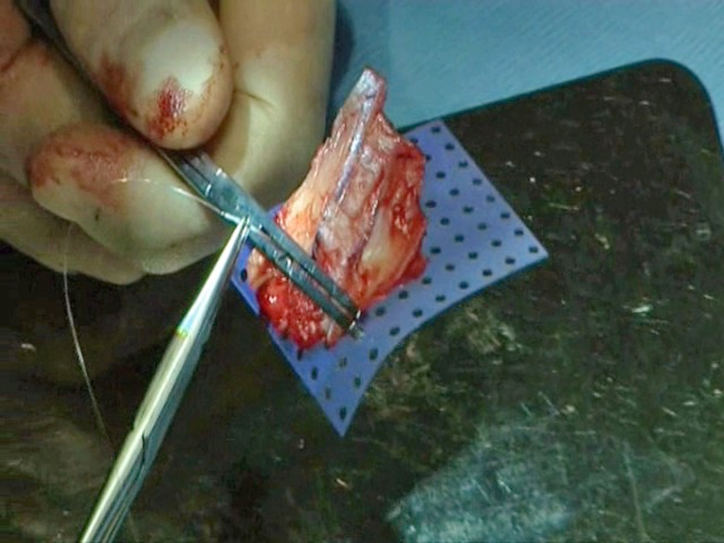

Once removed, the deviation can be corrected. The aim is to create multiple straight pieces of cartilage and fix them together as a straight septum. Fracture lines should be utilized and the cartilage divided along them (Figure 1).

In cases where the cartilage is twisted with no fracture lines the divisions are made in the areas of maximum convexity. The number of cartilaginous pieces varies from 2 to 6 in most cases. When the quadrilateral cartilage is severely resorbed or damaged, conchal cartilage is used to complete the septum in the same way after being straightened with incisions. We use perforated polydioxanone (PDS™) foil plates (Ethicon Inc, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey) as support for the “new” septal cartilage; the separate pieces of cartilage are sutured to the foil with 4/0 PDS sutures using Aiach forceps to hold them together (Figure 2).

Each piece of cartilage is sutured separately for secure fixation and the sutures should not go through the perforations of the foil. It is a good idea to draw or cut around the original quadrilateral cartilage so that an appropriate shape is obtained; a “tail” of PDS foil should be included to run posteroinferiorly for stability (Figure 3).

Any bony work needed should be done prior to reinsertion of the septal cartilage. Once the cartilage has been reshaped and sutured onto the PDS foil it is reinserted into the nose and sutured to the anterior nasal spine at the appropriate point; care must be taken not to attach the “new” septum more caudally than it should be. This should be done with a 4/0 PDS suture, initially secured through the anterior nasal spine periostium and soft tissue, and then passed through the PDS foil/cartilage graft and tied again. The second point of fixation is made into the upper lateral cartilages with one mattress suture using 4/0 PDS. The third point of fixation is with standard trans-septal mattress (quilting) sutures using 4/0 Vicryl rapide (Ethicon Inc) placed through the septal mucosa and PDS foil/cartilage graft to provide further support. This three-point fixation is sufficient to secure the septum in place without the need for suturing it to the nasal bones. It is essential that the cartilaginous septum fits precisely in the area of the original quadrilateral cartilage and is supplemented by auricular cartilage graft of it is too small. Only very occasionally a dorsal graft is needed.

The tip can be addressed as indicated, and closure is carried out in the standard fashion. Steristrips and plaster are applied, and removed one week later. A dose of intravenous co-amoxiclav is given at induction and continued orally for one week postoperatively.

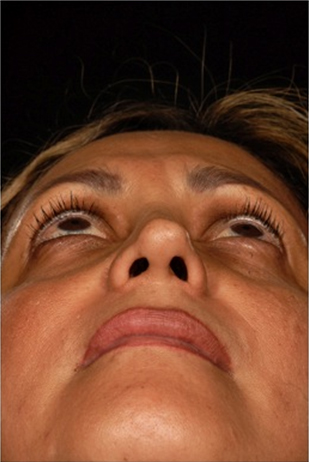

The following case illustrates the results of extracorporeal septorhinoplasty. A 40 year old woman presented following two previous rhinoplasties, requesting further revision to improve her nasal deformity and obstruction. Previous over-resection of her alar and upper lateral cartilages had resulted in a deviated nose and septum, with a narrow middle third and asymmetrical tip (Figures 4a-d).

The patient underwent an external approach revision septorhinoplasty, with an extracorporeal septoplasty using perforated PDS foil as described above. Conchal cartilage was harvested for spreader grafts, and was also used with PDS foil to create alar and columellar struts. Transdomal and interdomal suturing was performed with 5/ PDS foil, with routine closure and application of a plaster cast for one week. Postoperative recovery was uneventful and there were no complications.

At one-year follow-up, the patient’s septum remains straight, with a widened and straightened middle third and restored tip symmetry (Figures 5a-d).

The patient was completely satisfied with both the functional and aesthetic outcomes.

Discussion

Extracorporeal septoplasty was initially described in 1952 by King and Ashley.7 Since then, various authors have discussed their different techniques and outcomes. In 1995, Gubisch described his series of 1012 extracorporeal septoplasties, performed via an endonasal approach; he sutured the pieces of cartilage back together and reimplanted them without any graft for support.8 Senyuva in 1997 reported removal of the entire cartilaginous and bony septum via an external rhinoplasty approach. The dorsal and caudal septal edges are then reconstructed with an “L”-shaped strut cut from the quadrilateral cartilage.5 By 2005, Gubisch was also excising the entire bony and cartilaginous septum, and would occasionally use PDS foil for support. He describes various techniques to create a straight septum, including excision of redundant cartilage and resuturing, releasing incisions on one side of the cartilage, or smoothing both the cartilaginous and bony septum with a drill.6 More recently, a modified extracorporeal septoplasty technique has been described in which a small remnant of dorsal cartilage is preserved at the keystone area to increase stability.9 We feel that PDS foil provides all the stability needed, without the need to retain any cartilage, thereby improving results.

We have been using PDS foil to support the reconstructed septal cartilage for seven years, and have a series of over 100 patients. Others have reported their series supporting the use of PDS foil to improve the outcome of surgery, preventing recurrent deviations. Petropolous et al reported twelve patients over two years who underwent extracorporeal septo(rhino)plasty via an external approach. PDS foil was used as a scaffold to reconstruct a straight quadrilateral cartilage, in a similar way to the technique we report here.10 Similar small series have also been published.11,12 The largest series of extracorporeal septoplasty using PDS foil reported is of 396 patients, with a 93% success rate, satisfactory cosmesis and no immediate complications.13 Some series note symmetrical thickening of the septum for the first few weeks postoperatively, which has then resolved in all cases. The mirrors the authors experience who observed this in about a third of cases. This can be viewed as a recognized sequela rather than a complication.13,14

Animal studies have shown that polydioxanone PDS foil is completely resorbed by 25 weeks. It provides structural support for the repositioned cartilage as it heals, almost acting as a guide for tissue regeneration.15 Its use in growing rabbits reduced secondary deviations and prevented overlap of cartilage segments. There is also evidence that polydioxanone foil stimulates new cartilage growth within the nasal septum, with formation of histologically more mature cartilage.16,17 We feel it provides essential support for the refashioned septal cartilage, giving excellent functional and cosmetic results with no increase in complication rates.

References

1. Van Olphen AF. The septum. In: Gleeson M, Browning GG, Burton MJ et al, editors. Scott-Brown’s otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery, 7th edition. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008. p. 1569.

2. Grymer LF, Bosch C. The nasal septum and the development of the midface. A longitudinal study of a pair of monozygotic twins. Rhinology 1997;35:6-10.

3. Grymer LF, Pallisgaard C, Melsen B. The nasal septum in relation to the development of the nasomaxillary complex: a study in identical twins. Laryngoscope 1991;101:863-868.

4. Janfaza P, Montgomery WM, Salman SD. Nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses. In: Janfaza P, Nadol JB Jr, Galla RJ et al, editors. Surgical anatomy of the head and neck. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 265-266.

5. Senyuva C, Yücel A, Aydin Y et al. Extracorporeal septoplasty combined with open rhinoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg 1997;21:233-239.

6. Gubisch W. Extracorporeal septoplasty for the markedly deviated septum. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005;7:218-226.

7. King ED, Ashley FL. The correction of the internally and externally deviated nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 1952;10:116-120.

8. Gubisch W. The extracorporeal septum plasty: a technique to correct difficult nasal deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;95:672-682.

9. Jang YJ, Kwon M. Modified extracorporeal septoplasty technique in rhinoplasty for severely deviated noses. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2010;119:331-335.

10. Petropoulos I, Nolst Trenité G, Boenisch M et al. External septal reconstruction with the use of polydioxanone foil: our experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2006;263:1105-1108.

11. Gerlinger I, Kárász T, Somogyvári K et al. Extracorporeal septal reconstruction with polydioxanone foil. Clin Otolaryngol 2007;32:462-479.

12. Tweedie DJ, Lo S, Rowe-Jones JM. Reconstruction of the nasal septum using perforated and unperforated polydioxanone foil. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2010;12:106-113.

13. Boenisch M, Nolst Trenité GJ. Reconstruction of the nasal septum using polydioxanone plate. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2010;12:4-10.

14. Boenisch M, Nolst Trenité GJ. Reconstructive septal surgery. Facial Plast Surg 2006;22:249-254.

15. Boenisch M, Tamás H, Nolst Trenité GJ. Influence of polydioxanone foil on growing septal cartilage after surgery in an animal model. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003;5:316-319.

16. Boenisch M, Tamás H, Nolst Trenité GJ. Morphological and histological findings after typical surgical manipulations on growing septal cartilage in rabbits. Facial Plast Surg 2007;23:231-238.

17. Boenisch M, Mink A. Clinical and histological results of septoplasty with a resorbable implant. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;126:1373-1377.