Introduction

Fillers are now widely used in many aspects of cosmetic surgery, including the nose and its surrounding structures. The most common sites for filler injection on the face are the nasolabial fold, nose and forehead. Whilst filler injections have been established as relatively safe, minimally invasive and effective for facial rejuvenation, nevertheless they have also been associated with serious adverse outcomes, including vascular compromise, particular for injections to the nose. Furthermore, even if the injection is performed on the nasolabial fold, patterns of the vascular compromise are similar to that of injections on the nose, due to the anastomotic blood supply.

Fillers can be classified as temporary, semi-permanent and permanent fillers, according to the duration of their effects. In the past, permanent fillers were widely used, however in recent years they have been almost entirely replaced by absorbable fillers for facial cosmesis. This shift in popularity may be due in part to the potential reversibility of hyaluronic acid fillers with hyaluronidase. Furthermore, permanent fillers have the added disadvantage of potential migration, particularly when used on the nose, often making it appear wider and flatter over time. They can also cause a granulation and foreign body reaction, resulting in dorsal irregularity, chronic inflammation and deformation of the nose. Whilst absorbable fillers do not share much of the above side effects, nevertheless they have been associated with other adverse outcomes, which range from bruising and erythema, to infection and nodule formation, to the devastating sequelae of vascular compromise with possible skin necrosis.

Therefore, prior to embarking on filler injection, it is critical that the clinician first familiarizes themselves with the anatomy of the blood supply of the face and the characteristics of the chosen filler material. They must also have explained the possible risks of filler injection to the patients. If the adverse effects occur, they need to be treated promptly and without delay.

It is important to note that the vascular compromise following filler injection occurs over the span of approximately 7 days, not necessarily immediately after the injection. Therefore, if the patients complain of pain and other discomfort immediately after injection or 1 day following injection, the clinician should suspect vascular compromise and immediately start the intensive treatment. The visible lesions on the skin like bullae, abrasion and eschar do not often appear on the first or second day after injection, rather the skin lesions tend to gradually worsen over time.

The Blood Supply Around the nose

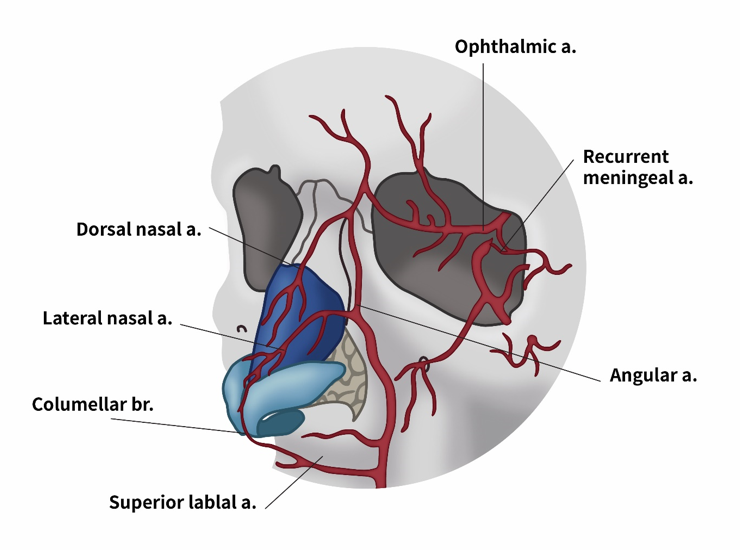

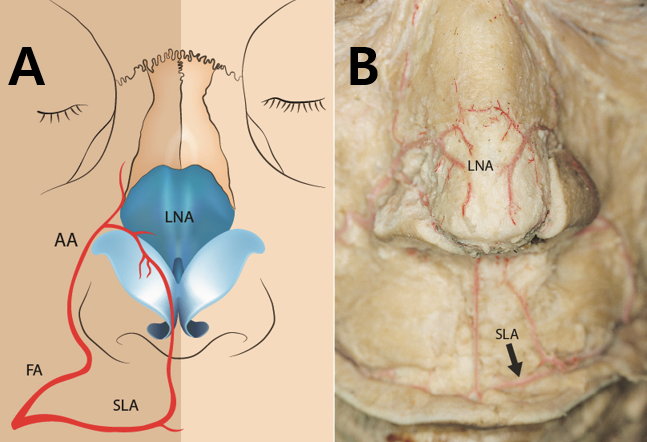

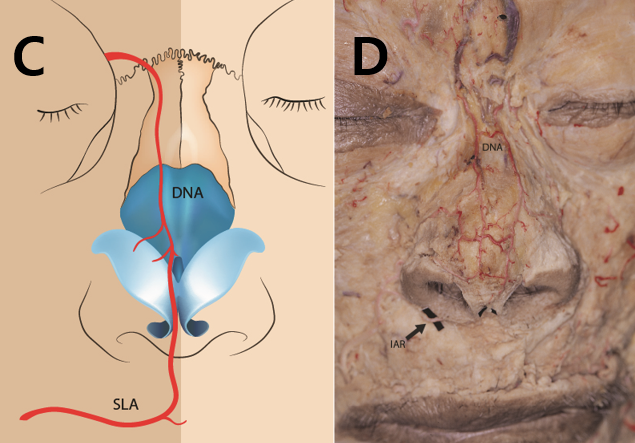

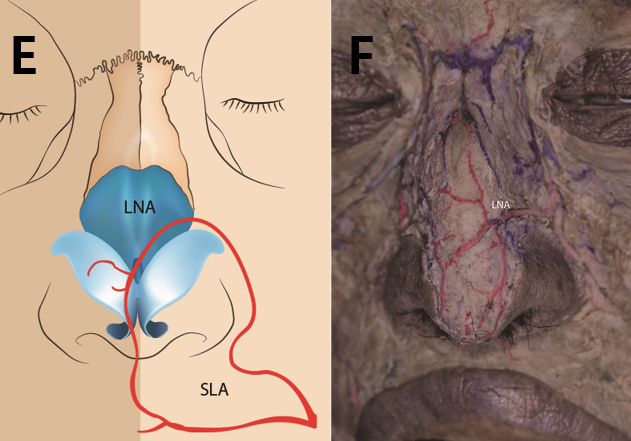

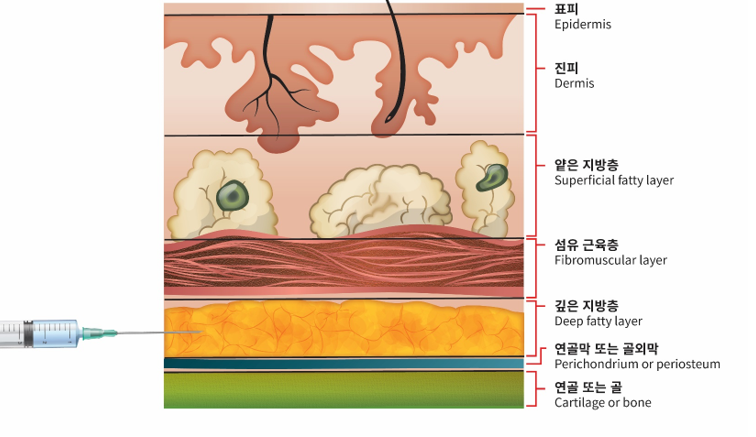

The nose is the protruding structure that receives the blood supply from a limited number of sources. Therefore, if the occlusion of major vessels occurs, the nose may be particularly vulnerable due to the lack of sufficient compensatory collateral circulation. The lateral nasal artery and the dorsal nasal artery are the main sources of blood supply to the nasal tip, which is also supplied by the columellar branch (Figure 1). However, sometimes variations in blood supply are observed. For instance, in one common variation the dorsal nasal artery is dominant with a small or absent lateral nasal artery, whilst in another known variant, the lateral nasal artery dominates without the dorsal nasal artery (Figure 2). The existence of these variations in blood supply suggests that the collateral blood supply could be limited when the main artery is obstructed. Due to these anatomical characteristics, vascular compromise on the nose or around nose may occur when the main vessel is obstructed, either by embolism or vascular compression. The blood vessels are mainly located in the superficial fat layer and also supply blood throughout the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). Therefore, when performing filler injection, it is necessary to understand the anatomical characteristics and distribution of these vessels and the adverse effects that may occur during filler injections to avoid catastrophic vascular compromise.

Figure 1. The angular artery and superior labial artery are branches of the facial artery, which arises from the external carotid artery. The lateral nasal artery branches from the angular artery to supply the nasal tip. The dorsal artery is a branch of the ophthalmic artery, which arises from the internal carotid artery.

Figure 2. There are 4 main types of patterns of blood supply to the nose: from the ipsilateral lateral nasal artery (A, B), from the ipsilateral dorsal nasal artery (C, D), from the contralateral lateral nasal artery (E, F), and from the contralateral dorsal nasal artery (G, H).

- AA : Angular artery

- DNA : Dorsal nasal artery

- FA : Facial artery

- LNA : Lateral nasal artery

- SLA : Superior labial artery

Complications after filler injection

Complications after filler injections to the nose can be divided into early and late complications. Early complications include pain, bruising, infection, edema, asymmetry, hyper-sensitivity, skin necrosis and blindness. Late complications include nodule formation, granuloma, bumps, broadening of the nasal bridge, discoloration, skin irregularity, neoplasm etc. Surgical removal of permanent filler material can result in skin irregularity and cause serious skin damage, such as skin perforation or thinning and subsequent necrosis (Table 1).

Table 1. Complications after filler injection

Early complications

- Pain

- Swelling

- Asymmetry

- Infection

- Bruising

- Ecchymosis

- Hypersensitivity

- Pustule

- Eschar

- Skin erosion

- Multiple ulceration

- Skin necrosis

- Blindness

Late Complications

- Broad nasal bridge

- Skin color change; Redness, White color

- Skin irregularity

- Granuloma or nodule formation

- Neoplasm

During surgical removal

- Skin irregularity

- Skin perforation

- Skin necrosis

Vascular compromise

Vascular compromise is undoubtedly one of the most serious complications after filler injection. It appears to be directly related to obstruction, compression or damage to the local vasculature. An understanding of the blood supply around the nose is therefore important when studying the mechanism of vascular compromise.

1) Pathophysiology of vascular compromise

As mentioned above, vascular compromise is closely related to the blood supply around the nose. If the vessels are obstructed, vascular compromise around the nose occurs. The pathophysiology of vascular compromise due to impairment of the blood supply is as yet still not clearly understood, however we can divide the causes of vascular compromise into arterial embolization and non-arterial types, based on the pattern of the lesions.

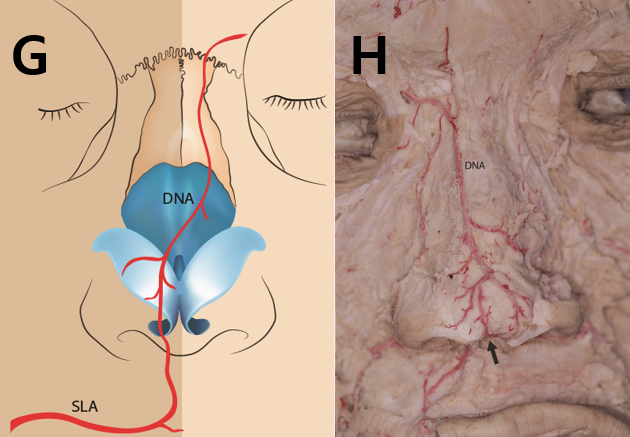

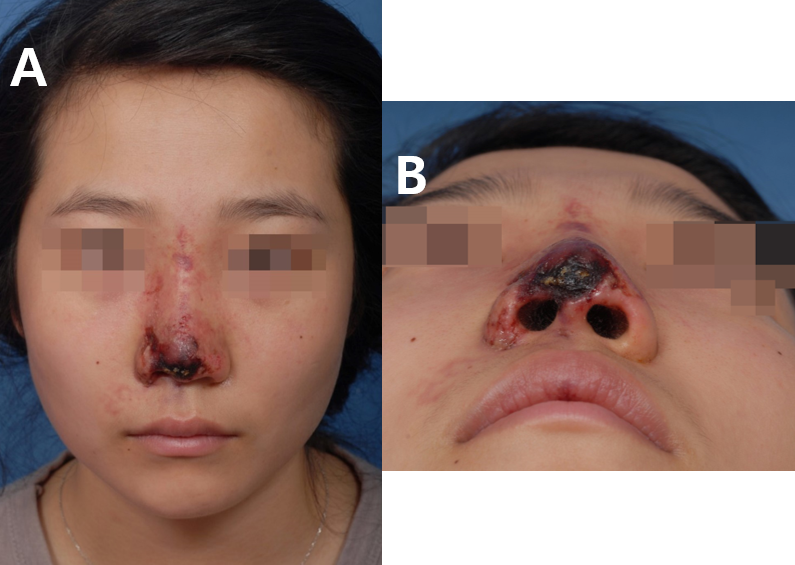

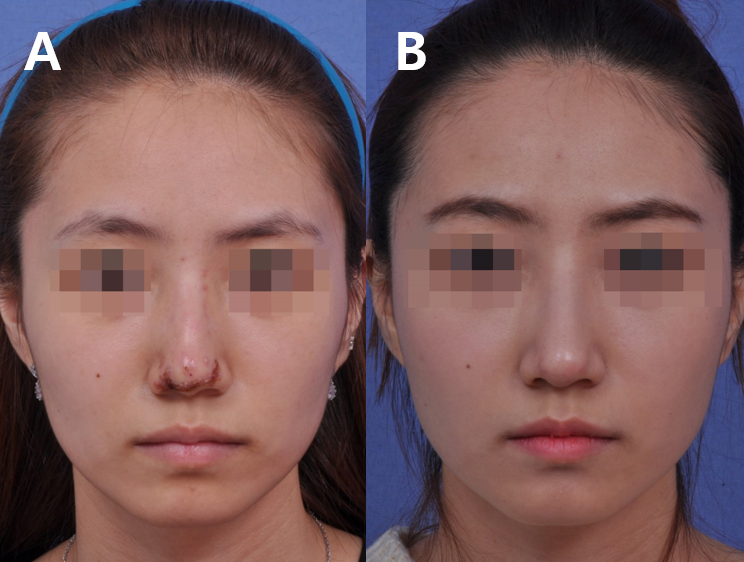

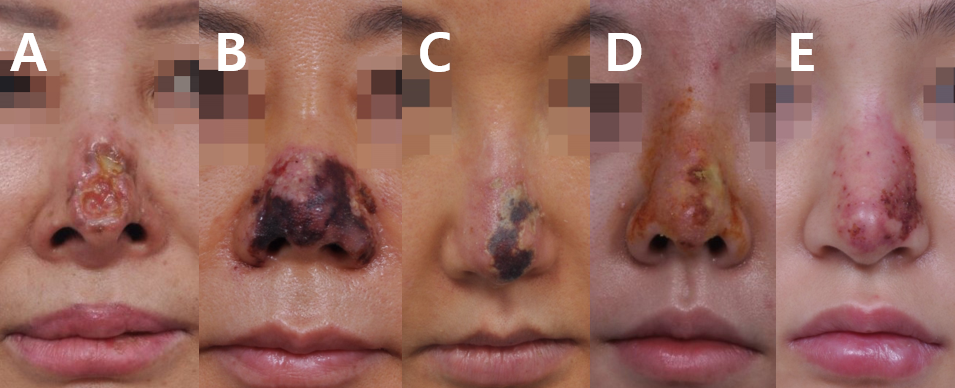

Arterial embolization is caused by the precise injection of the filler material into the artery, such that it acts as an embolism. Arterial embolization usually causes abrupt necrosis following a period of blanching with associated heating sensation and acute pain (Figure 3). Its progression can be either rapid or at a more moderate pace, over the span of 5 to 7 days (Figure 4). In the case of rapid progression of arterial embolization, eschar and ulceration appear as an early symptom and the subsequent sequelae is generally devastating. On the other hand, if the progression is at a more moderate pace, with vesicles, blisters or multiple ulceration formation as the early symptoms, then the sequelae tends to be comparatively milder (Figure 5).

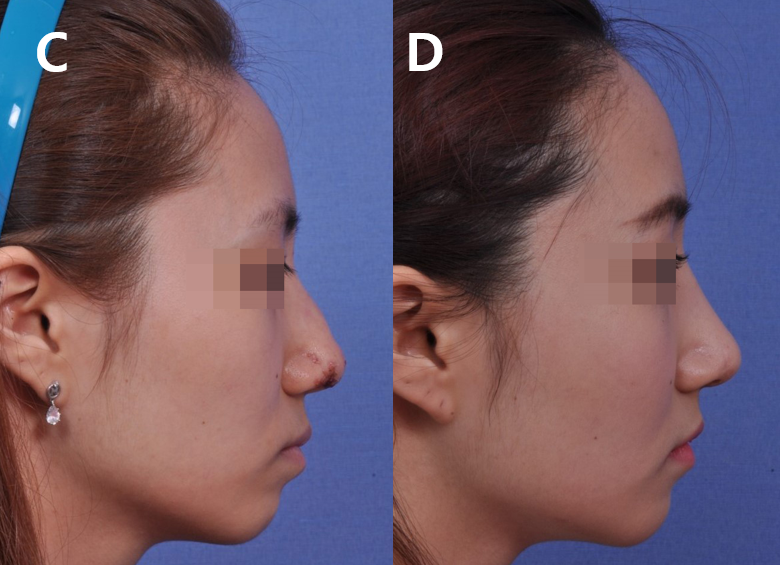

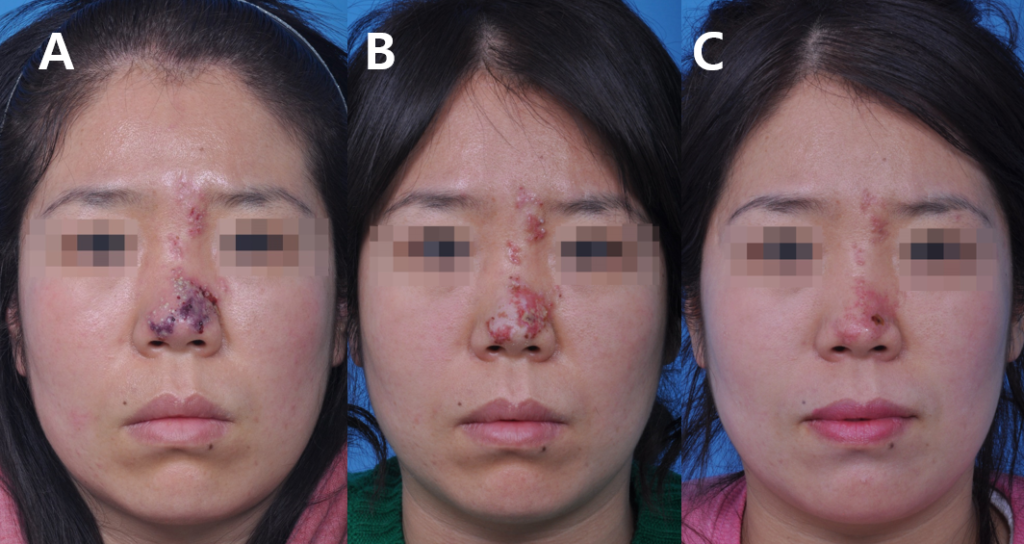

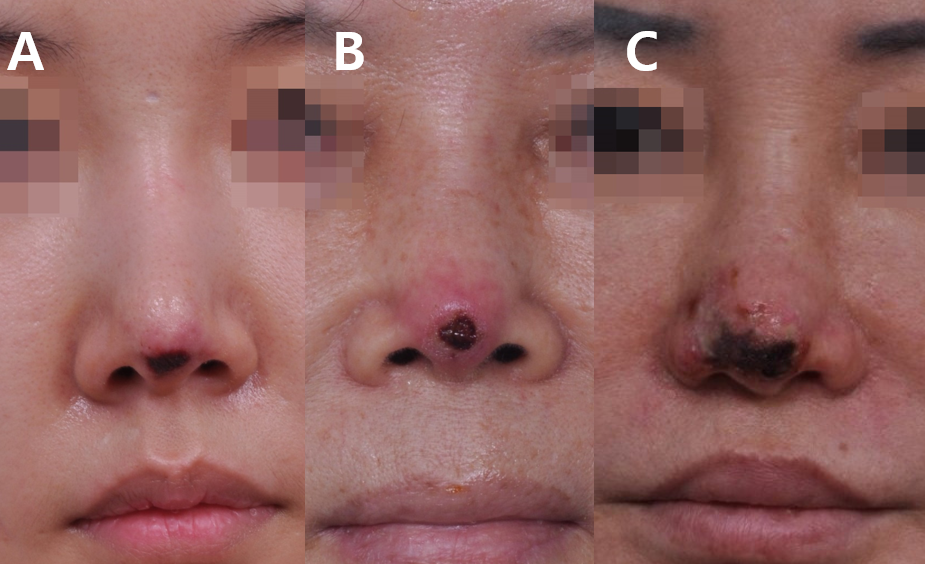

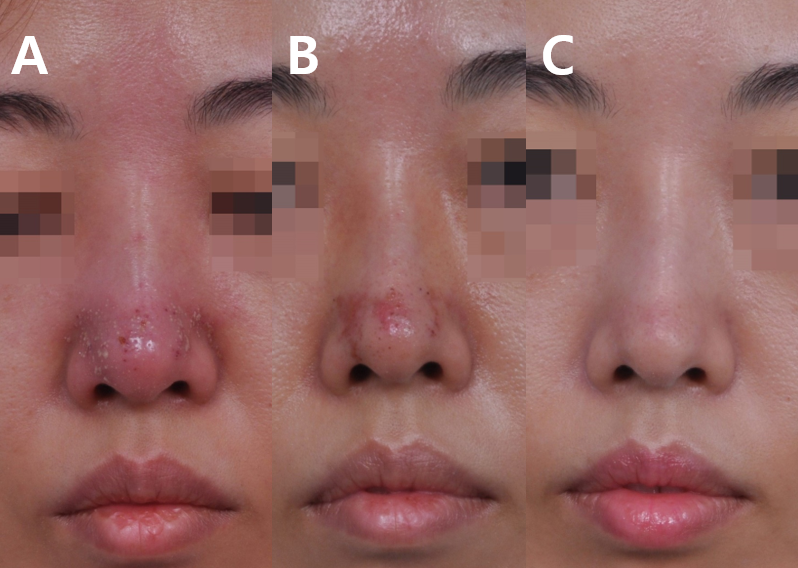

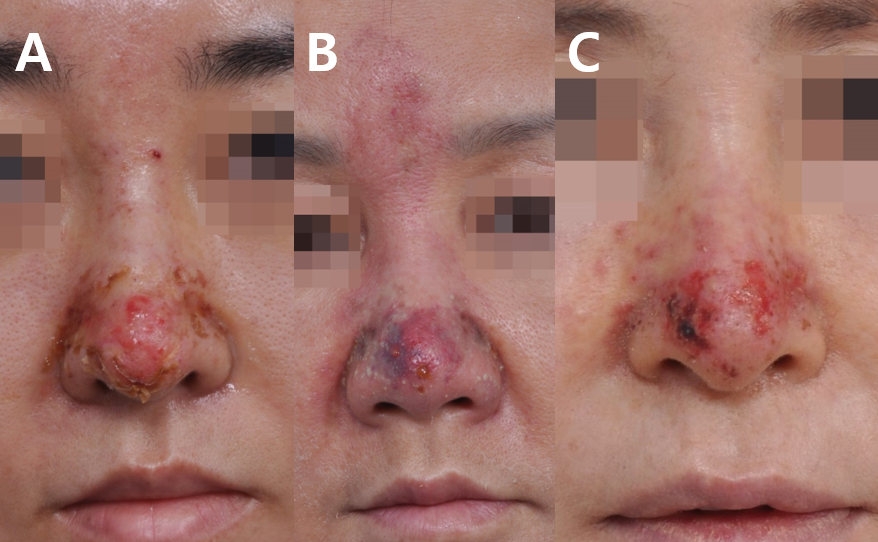

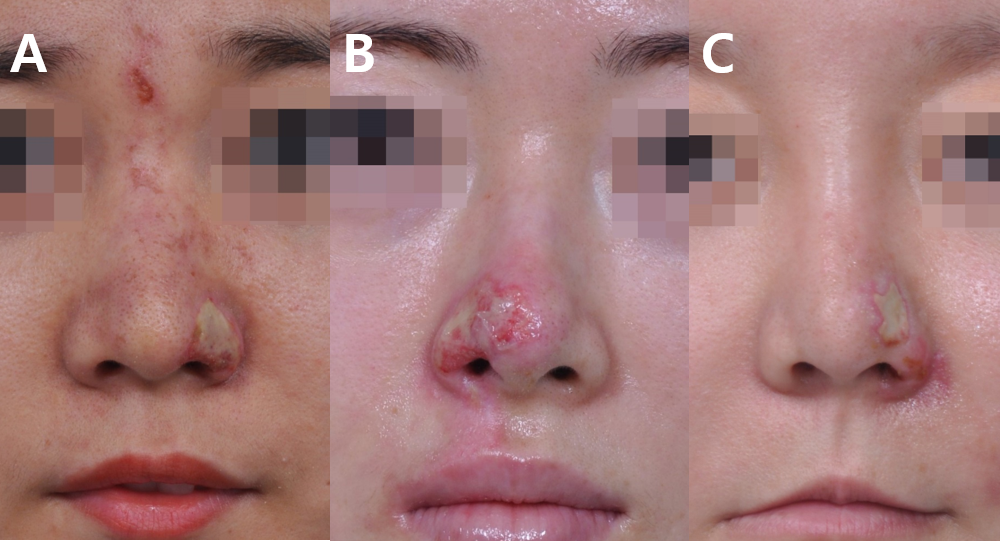

The second type of vascular compromise is the non-arterial type and likely due to vascular compression, although the exact mechanism has not yet been accurately determined. It has however been hypothesized that large amounts of filler in a finite space with associated edema might result in compression of neighboring vessels to cause vascular compromise. Another potential mechanism of injury is from the chemotactic effect due to hypersensitivity to the filler material, leading to damage and destruction of the adjacent vessels. It is important to note however that the symptoms resulting from non-arterial injury are not as severe as that which occurs with arterial embolization; the progression of necrosis, as characterized by the development of eschar, is not as rapid and recovery is more likely (Figure 6). Injury by vascular compression typically presents with reticulated erythema, ecchymosis, vesicles, pustules, multiple erosions and abrasions (Figure 7). It can be further categorized into local or widespread. Widespread non-arterial type lesions have a worse prognosis and may retain some sequelae despite early treatment, whereas in the case of more localized lesions, early treatment will often result in a better recovery without any long-term sequelae. (Figure 8) (Table 2).

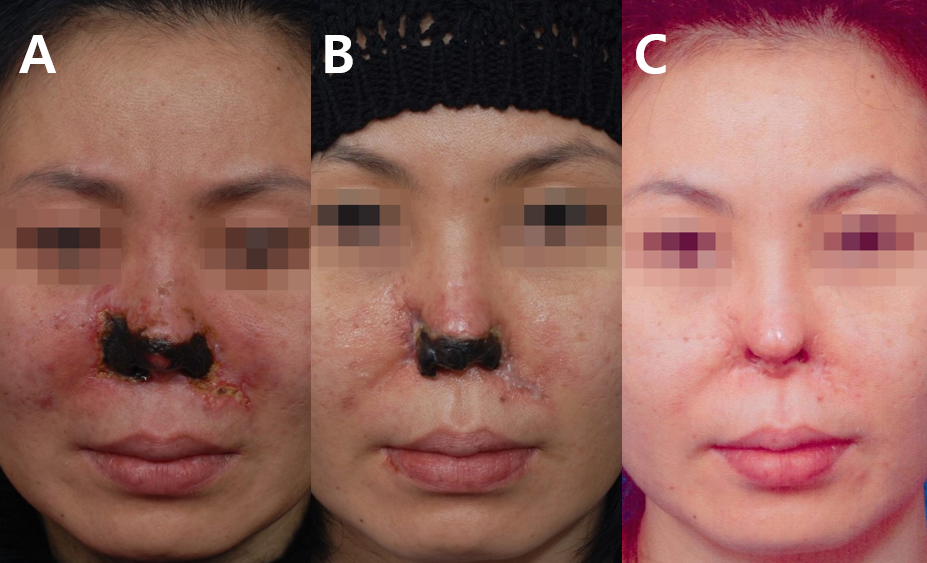

Figure 3. There is severe necrosis at 3 days after non-absorbable filler injection. There is eschar formation with skin necrosis and dark red erythematous lesions (A, B).

Figure 4. There is severe necrosis on the left ala and surrounding areas at 6 days after filler injection (A, B). Computed Tomography shows the engorged left facial artery with a normal sized right facial artery (C). It seems that the obstruction of the left sided vessel caused the engorgement of left facial artery.

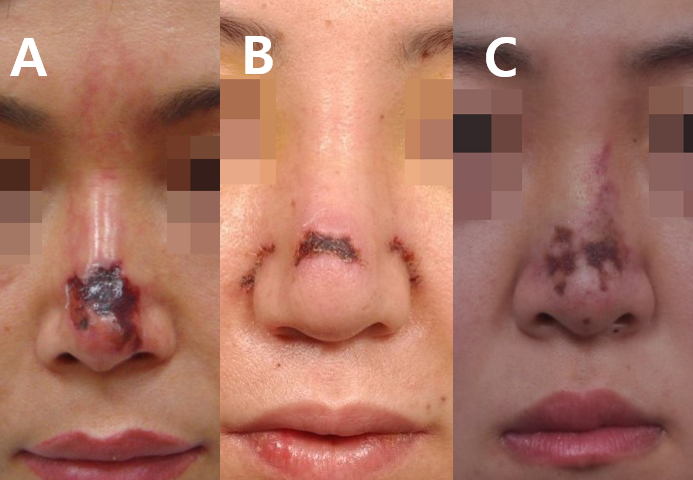

Figure 5. At 3 days after filler injection, the skin appears dark red with pustules and speckled whitish crust (A). Erosion occured at 8 days after injection (B), and there is contraction of the right ala, causing it to appear smaller than the contralateral side at 5 months after injection (C).

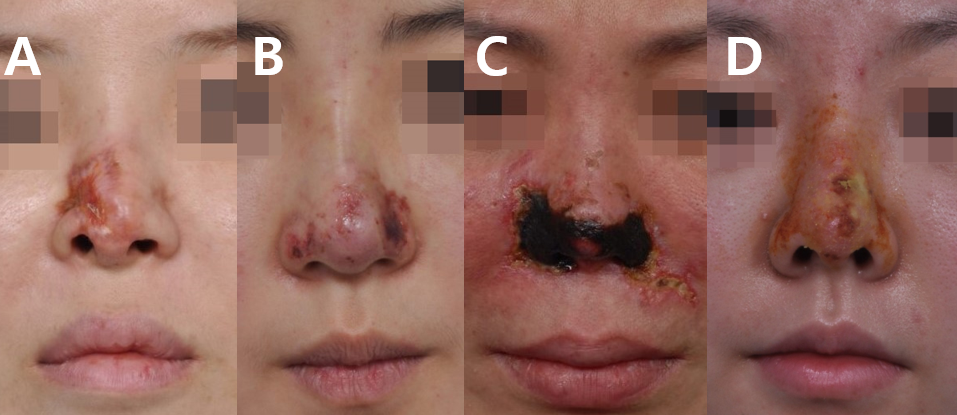

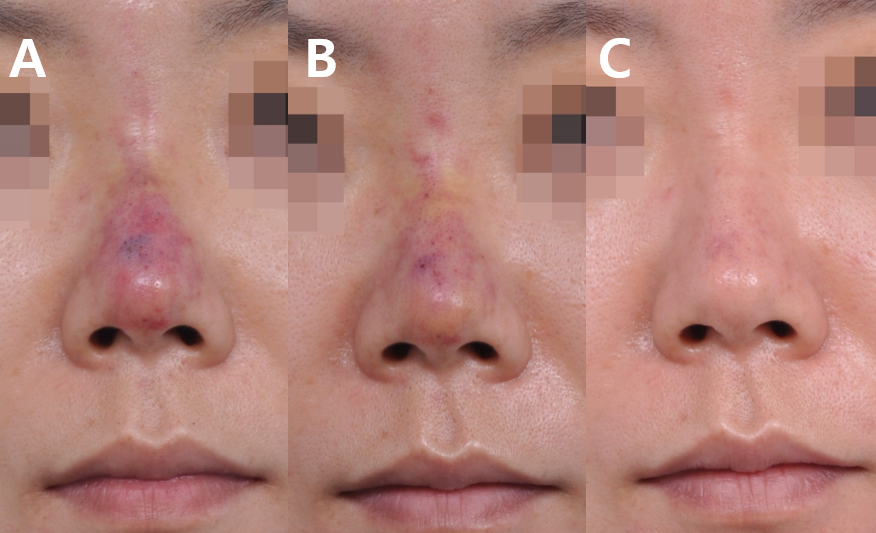

Figure 6. Pustules and erythema on a lesion after injection, but with eventual almost complete recovery (A, B, C, D).

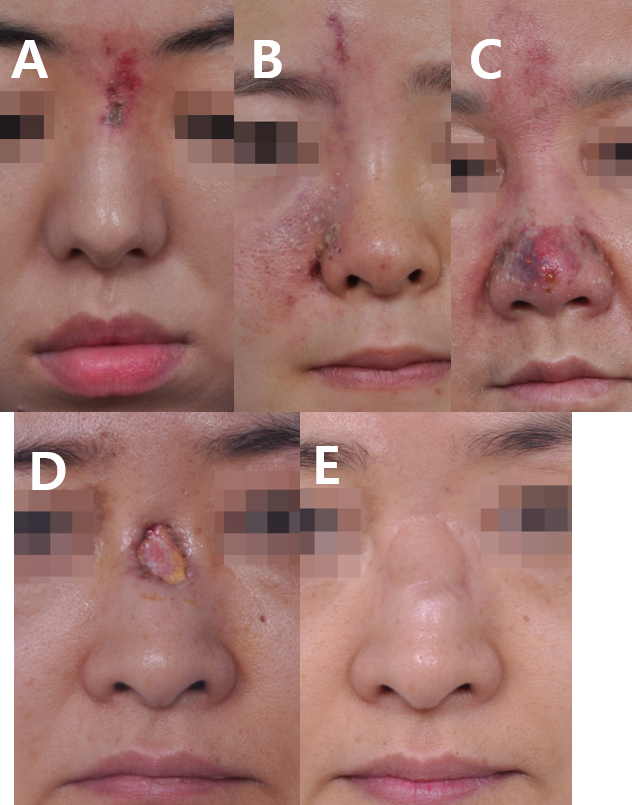

Figure 7. At 3 days after injection, small areas of dark red erythema, vesicles and pustules appeared (A). Multiple erosions and eschar appeared at 7 days after injection (B), but the lesions showed signs of good recovery at 16 days after injection (C).

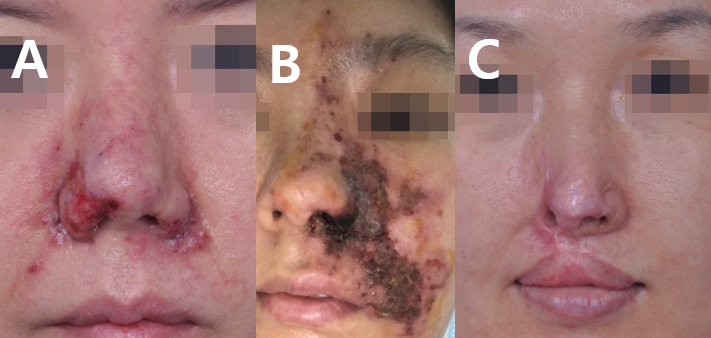

Figure 8. Widespread lesion of the non-arterial type. Venous mottling appeared at 1 day after injection (A) and broad crusting and erythema remained at 16 days after injection (B). It left a defect of the left ala, even though it is of the non-arterial type because of its widespread nature (C).

Table 2. Symptom of arterial and non-arterial type

—————————————————————–

Arterial type

-rapid progression of necrosis with eschar and ulceration within 7 days

-dark red discoloration of skin after filler injection

-necrosis progresses whether the lesion is widespread or localized

Non-arterial type

-symptoms appear over a relatively slow progression after injection with good recovery

-Ecchymosis, dark red erythema, vesicles, pustules, whitish ulceration, erosion

-Permanent sequelae by scar contracture is possible

-High chance of permanent sequelae if the lesion is the widespread type

———————————————————————–

2) Distribution pattern of nasal vascular compromise

The pattern of vascular compromise follows the blood vessel distribution. As the vessels are connected to each other, they are difficult to classify clearly. However, they can be divided into lesions of the nasal bridge, nasal tip, and ala, lesions involving more than 2 nasal subunits, and lesions in conjunction with other neighboring structures such as the lips (Table 3). In addition, the pattern and outcome of the lesions differ according to the cause, which is either arterial embolization or vascular compression.

Table 3. Distribution pattern of nasal vascular compromise

——————————————————-

Nose bridge necrosis

Tip necrosis

Tip & bridge necrosis

Alar necrosis

Tip & alar necrosis

Broad necrosis

Combined necrosis with other structures

———————————————————

(1) Nasal bridge necrosis

The lesion on the nasal bridge can be assumed to be associated with the dorsal nasal artery (Figure 9). Blood vessels are connected to each other, so it is difficult to clarify precisely which vessel is involved.

Figure 9. Different cases of nasal bridge necrosis (A, B, C)

(2) Nasal Tip necrosis

The lesion can be assumed to be associated with the columellar and lateral nasal artery (Figure 11), and is one of most common lesions in filler-associated vascular compromise.

Figure 10. Different cases of nasal tip necrosis (A, B, C).

(3) Nasal tip and Bridge

Obstruction of the columellar artery, dorsal nasal artery, and lateral nasal artery could be associated with nasal tip and bridge lesions (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Lesion of vascular compromise on the nasal tip and ala are shown (A, B, C, D, E).

(4) Nasal Ala

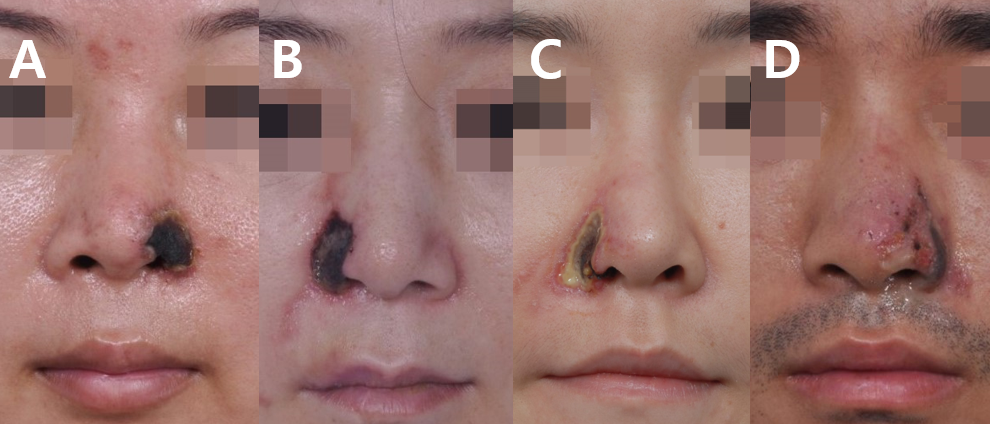

Obstruction of the lateral nasal artery may cause nasal alar necrosis (Figure 12). The lesion may occur on both sides of the ala, but that is uncommon. Unilateral lesions with alar necrosis are one of the most common patterns of vascular compromise.

Figure 12. Lesion of vascular compromise on the nasal ala (A,B,C,D)

(5) Nasal tip and ala

The lesion on the nasal tip and ala is thought to be related to obstruction of the columellar branch and the lateral nasal artery (Figure 13). This lesion is the most common form of vascular compromise after filler injection on the nasolabial fold, as the lateral nasal artery is the main source of blood supply to the tip and ala.

Figure 13. Lesion of vascular compromise involving the nasal tip and ala, which are the most common types following nasolabial fold filler injection (A, B, C, D).

(6) Glabella and Bridge necrosis

Lesions of the glabella are usually accompanied by lesions of the nasal bridge and also associated with complications of the eye (Figure 14). It is assumed to be associated with the ophthalmic artery and the dorsal nasal artery.

Figure 14. The lesion of vascular compromise is on the glabella and nasal bridge (A, B, C). The defect over the glabella area (D) was reconstructed by surgery (E).

(7) Broad lesion

The lesion was spread across the whole subunits of nose, and this was assumed to be associated with the angular artery or the facial artery (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Broad lesions of vascular compromise.

(8) Combined necrosis with other structures.

The lesion can be accompanied by lesions involving the lip, eye, and philtrum. The facial artery, angular artery or ophthalmic artery are presumed to be involved in such cases (Figure 16).

Figure 16. Combined necrosis with other structures. The lesions on the nose are accompanied by orbital (A, B), lip (C, D) and philtrum (E) involvement.

3) The pattern of vascular compromise by vessels.

(1) Artery related vascular compromise

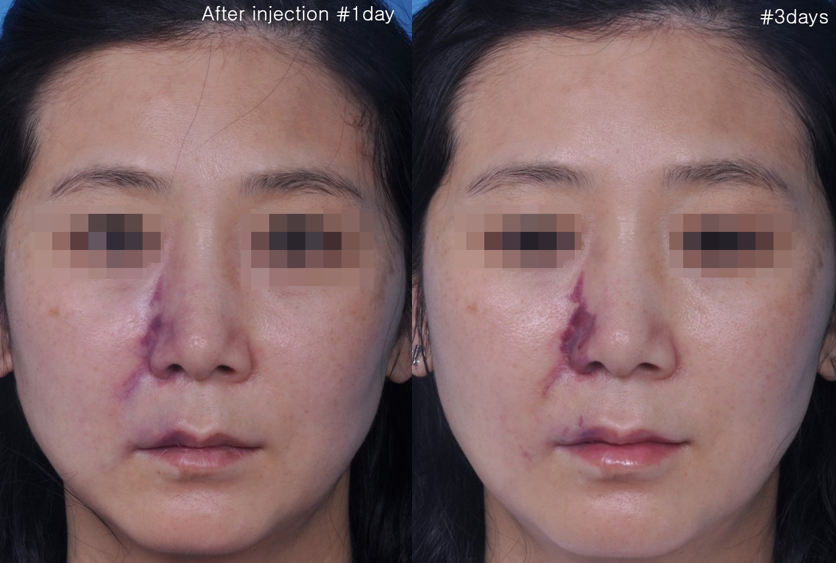

Arterial embolization can occur by direct injection of filler into the artery. Most of these cases show rapid progression of necrosis that evolves into black eschar within 7 days after filler injection. It has a poor prognosis, regardless of the lesion extent and even despite immediate and intensive treatment (Figure 17). On the other hand, non-arterial types have a more variable prognosis, depending on the extent of the lesion.(Table 2). In the case of arterial embolization, the formation of vesicles, pustules, a whitish crust or erosion is rare, since they are the hallmark characteristics of the less aggressive non-arterial type. We can predict the prognosis of arterial embolization by the rapidity and severity of the case development over time (Figure 18).

Figure 17. Severe necrosis developed rapidly after injection of absorbable filler into the nasolabial folds and nasal tip. At 9 days after injection, severe necrosis was observed (A, B, C). Vesicles, pustules, a whitish crust and erosion are slightly visible at the periphery, but the necrosis progressed immediately in the central part of the lesion.

Figure 18. The patient visited our clinic at 1 day after injection (A) and we start immediately commenced intensive treatment with hyaluronidase and hyperbaric therapy. These pictures show the progression of arterial vascular compromise over time at 3 days (B), 5 days (C), 6 days (D), 8 days (E), 11 days (F), 14 days (G), 18 days (H), 21 days (I), 29 days (J), 50 days (K), 80 days (L) after filler injection. We performed reconstructive rhinoplasty (M) followed by a second stage operation (N). Necrosis progressed immediately without associated vesicle, pustule, whitish crust or erosion formation.

(2) Non-artery related vascular compromise

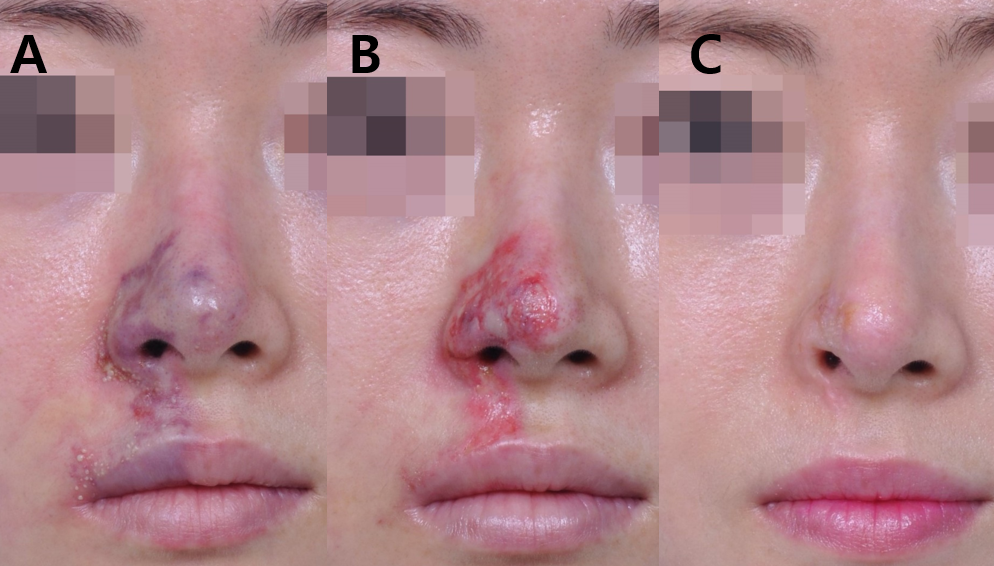

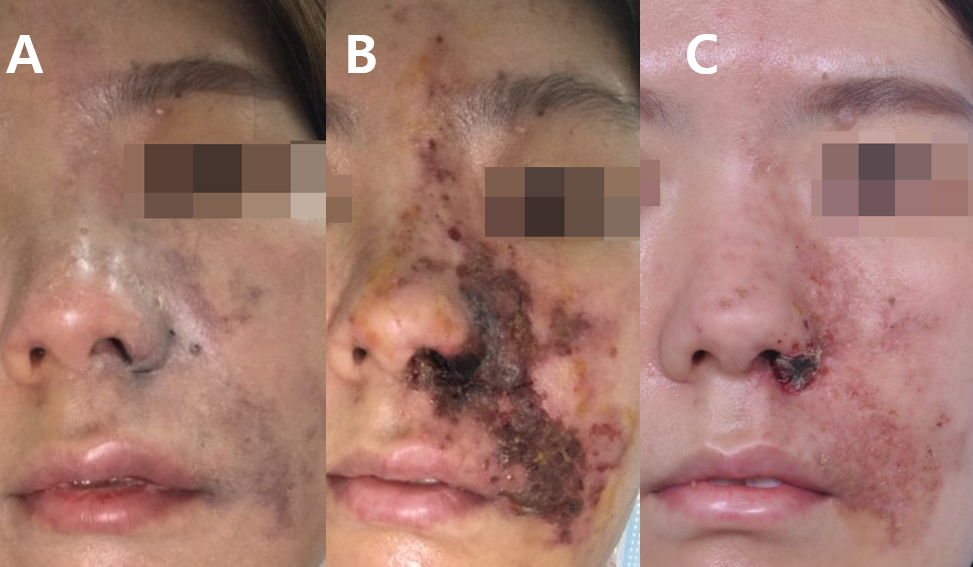

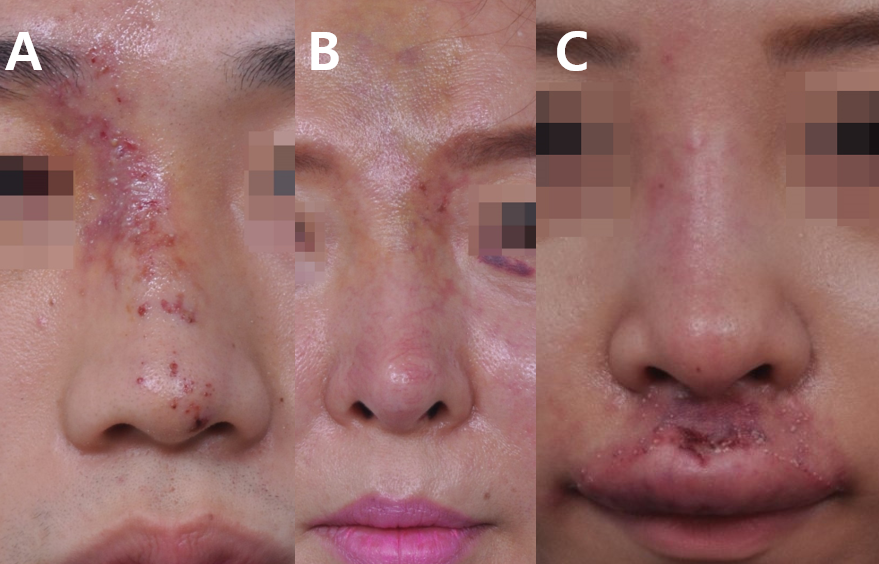

The non-arterial type of vascular compromise is not caused by direct injection of filler into the vessels, but instead through mechanisms discussed earlier (see pathophysiology section), resulting in vascular compression and vessel damage. Non-arterial types present with reticulated erythema, ecchymosis, erosion of the epidermis and the formation of vesicles, pustules, crusting and dark red discoloration like bruising (Figure 19). The skin turns dark and red with erosions. however necrosis does not generally progress rapidly (Figure 20). Unlike the arterial type, there is a high chance of recovery without any significant long-term sequelae, particularly if immediate and intensive treatment is promptly implemented (Figure 21). Although non-arterial types have a better prognosis than the arterial type, if the lesions are widespread with multiple ulcerations as opposed to just crusting and erosion, the likelihood of having complete recovery is lessened (Figure 15B, Figure 24), since ulcerations often result in contracture of the skin during the secondary healing process.

Figure 19. There is erythematous change of the whole lesion, with the formation of vesicles, pustules, ecchymosis and dark red change that resembles bruising with partial erosion (A). However most of the lesion has completely recovered over time (B, C).

Figure 20. Variable progress seen in non-arterial vascular compromise cases. There is erythematous change with black crust, abrasion and erosion (A). Another case that presented as whitish pustules and dark red skin color changes with partial erosions (B, C). Some cases show evidence of abrasion and black crust with loss of epidermis (D, E).

Figure 21. Vascular compromise along the distribution of the angular artery was completely recovered as a result of immediate and intensive treatment. In this case there were white crusts and pustules at 4 days after filler injection (B) and the deterioration was apparent when compared to the initial appearance on the first day of injection (A). There was black crust at 6 days after injection and the long-term follow-up photo demonstrates that the lesion made a good recovery without any sequelae (C,D).

Figure 22. Widespread lesions of non-arterial vascular compromise may cause partial necrosis with permanent sequelae.

Figure 23. There was an erythematous lesion at 2 days after injection, but the lesion was completely recovered after immediate and intensive therapy (B, C).

Figure 24. Most severe cases of non-arterial lesions, where there are multiple deep ulcerations with necrosis (A, B, C), will result in scar contracture deformities due to the ulceration’s secondary healing process

As mentioned above, we can predict the prognosis of the vascular compromise to some extent and can formulate treatment strategies depending on the pattern and the cause of the vascular compromise.

5. Prevention of Complication

Vascular compromise after filler injection has serious consequences; therefore its prevention cannot be overemphasized. Vascular compromise can cause necrosis, however it can also result in blindness. Choosing safe materials and familiarizing oneself with the anatomy of the injection sites are of vital importance, as is regularly checking for vascular injury by intermittently aspirating, whilst injecting where possible.

To reduce the acute complications, it is important to know which layer of the skin you want to inject the filler into and to limit the injection to that specific layer where possible. We should inject the filler either in the deep fatty layer or below it, and should avoid filler injection to the superficial fatty and SMAS layers in which blood vessels are located (Figure 25). When injecting the filler it is safer to inject with the needle moving backwards rather than forwards. For filler augmentation on the dorsum, the injection should be performed on the center of the nose to reduce vascular compromise, since the blood vessels on the dorsum are mainly located on both sidewalls.

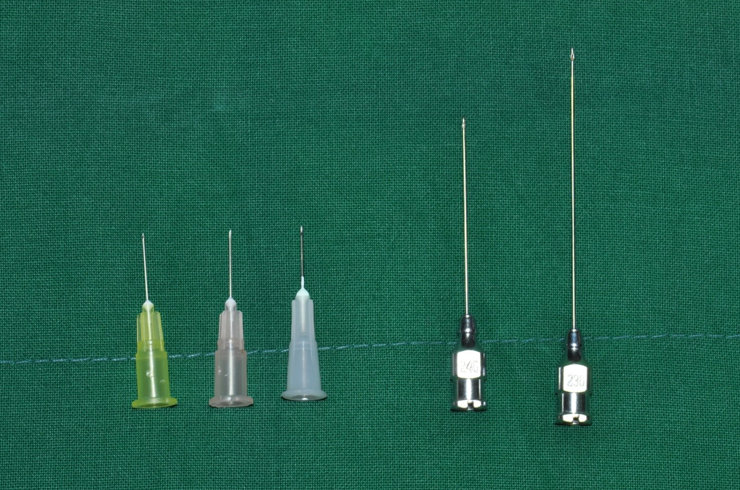

Use of a catheter or blunt needle with a hole on the side of the syringe rather than a sharp needle with the hole at the tip is considered safer and therefore recommended (Figure 26), since there is a greater risk of injecting filler material directly into blood vessels when sharp needles are used (Table 4). It is also safer to use absorbable fillers rather than non-absorbable fillers, because of the reversibility of the former using hyaluronidase.

Before the procedure, the surgeon should also get consent and explain to the patient that vascular compromise with necrosis and blindness can occur in rare cases.

Table 4. Safe filler injection principles

———————————————

Select safe filler materials

Use absorbable filler rather than Non-absorbable filler

Understand facial anatomy

Use a blunt cannula rather than sharp needle

Proper layer with proper filler

Inject into one layer

Inject whilst withdrawing the syringe

Aspirate during injection as often as possible

Careful checking after injection – blanching, heat sensation, pain

———————————————–

Figure 25. We recommend to inject the filler into one layer, and the layers may vary depending on the type of filler. However as a general rule, the ideal layer for safe and effective filler injection is the deep fat layer or below.

Figure 26. Different types of needles used for filler injection. On the left: 3 sharp needles used for filler injection. On the right: 2 blunt cannulas commonly used for fat injection. Needles intended for filler use are often injected vertically into the skin at the desired area. However, cannulas frequently used for fat injection are considered safer and often also used for filler injection. Since the cannula is blunt and has a hole on the side, it is less likely to puncture and inject filler directly into blood vessels.

6. Treatment

Following the injection, the patient should be checked for any evidence of blanching, pain, or heating sensation. If the pain or heating sensation persists after the patient returns home and the skin turns pale or ecchymosis appears, the patient should be instructed to contact the clinic without delay for immediate treatment. The first sign of vascular compromise, paleness or pain, is often mistaken for general symptoms after injection. The degree of necrosis will often be worse if the window period for early intervention is missed, hence if there is any suspicion or doubt of there being vascular compromise, the clinician should err on the side of caution and start immediate intensive treatment as soon as possible. We can divide the treatment of vascular compromise into medical treatment and surgical treatment.

1) Medical treatment

Once the progression of vascular compromise is confirmed, intensive medical treatment should begin immediately. Injection of a minimum of 200 to 300 USP units of hyaluronidase (spread over the entire area of impending necrosis) is essential. This should be repeated daily for a minimum of 2 days until signs of either permanent necrosis or reestablished blood flow appear. The clinician should not remove the crust. Instead, regular wet dressing with Vaseline gauze or antibiotic ointment is recommended, to prevent and mitigate the skin defect. In addition, hyperbaric oxygen and intravenous prostaglandin should be given once a day for approximately 7 days. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is considered to be essential to treat vascular compromise, performed at 4 ATA (atmosphere absolute), twice daily for 90 minute intervals for more than 7 days (Figure 27). Prophylactic antibiotic, warm massage and stem cell injection may also be helpful adjuncts and should be considered (Table 5).

Figure 27. Hyperbaric oxygen chamber

Table 5. Medical treatment of vascular compromise

———————————————————-

Hyaluronidase injection

Warm Massage

Prostaglandin E2, PGE2 (EglandinⓇ)

– IV Regimen 1 ; Eglandin 1-2 ml mix with Normal Saline once daily for 3-7 days

– Oral ; Limaprost (Prostaglandin) 1-2 Tab three times daily

Hyperbaric treatment

Stem cell injection

Antibiotics

———————————————————–

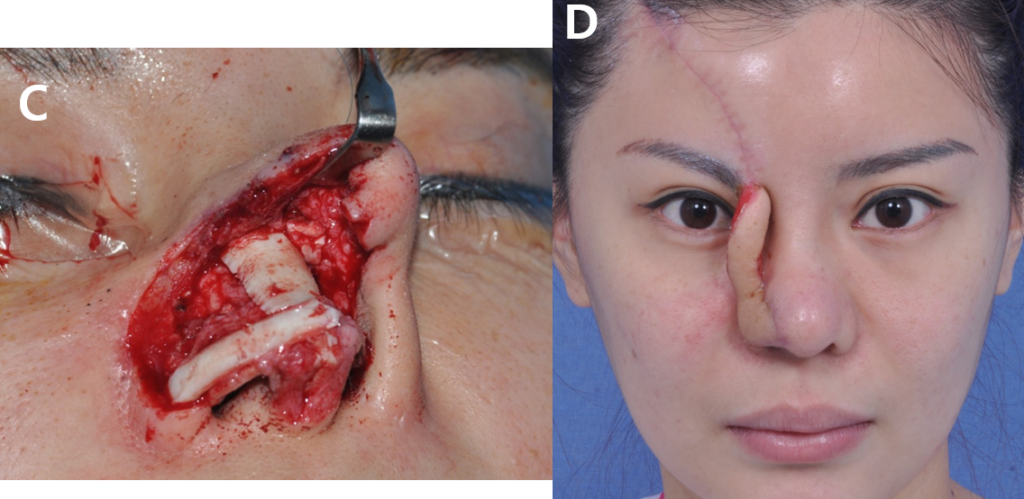

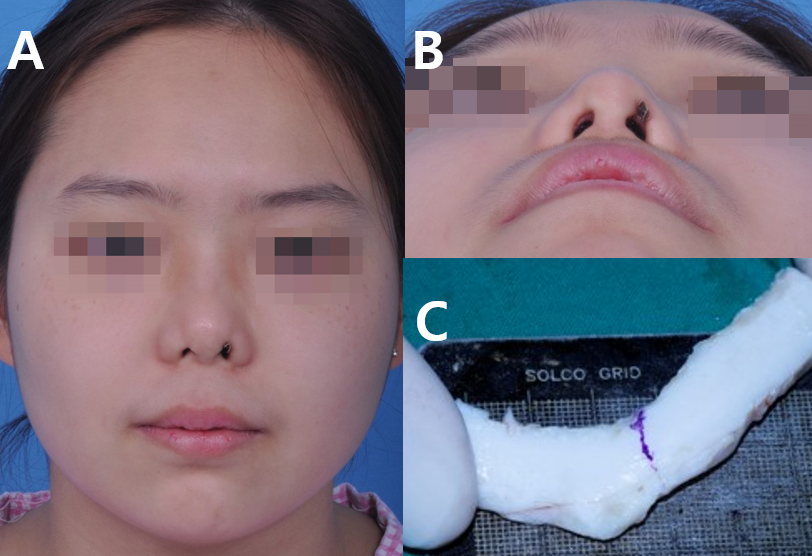

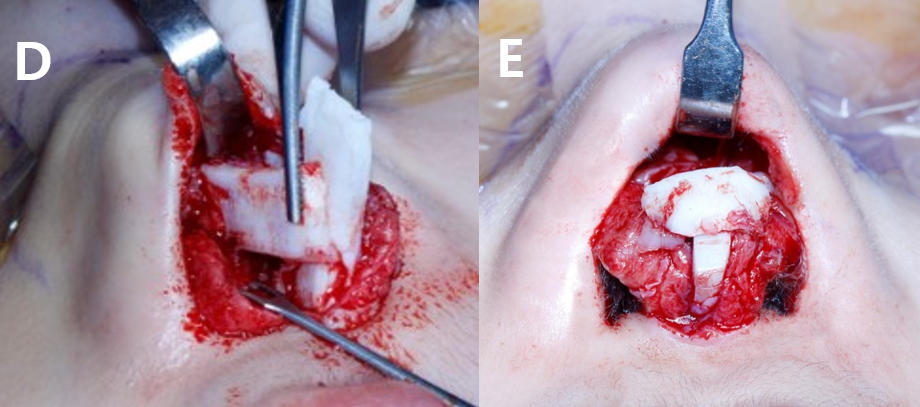

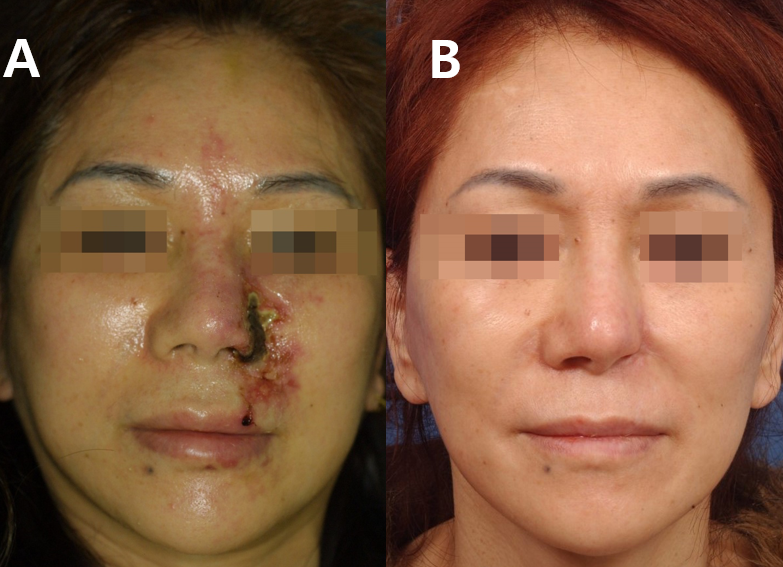

2) Surgical treatment

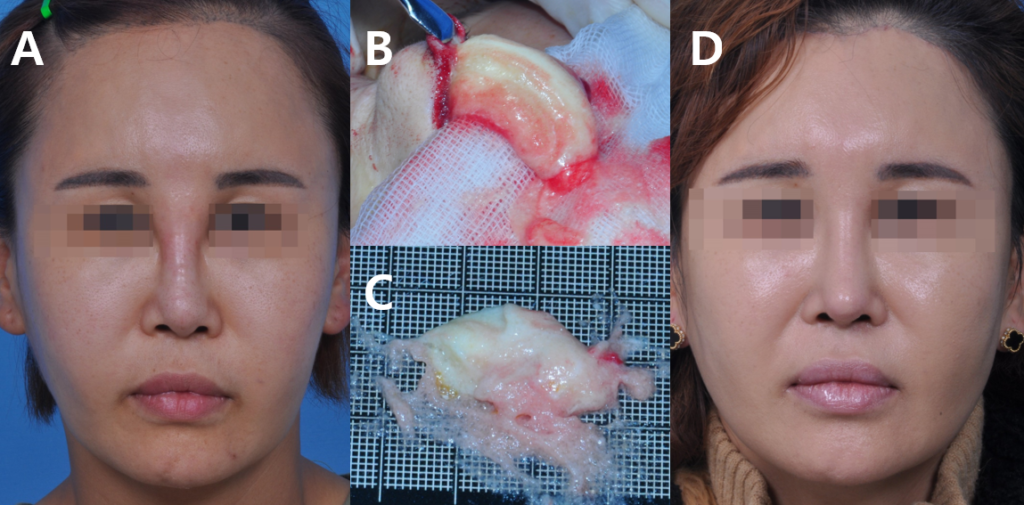

Surgical treatment is required when severe scarring and nasal defects occur after the acute stage or when the delayed contracture and deformation has occurred (Table 6). If the color of the skin changes after injection, or the nose is flattened or bumpy after a long time following filler injection, it is necessary to first remove the filler material. We recommend where possible that the filler be removed as an en-bloc piece. Polyacrylamide series fillers such as Aquamid, Interfall, and Amazing Gel, which are liquid fillers, can potentially be removed by the squeezing method during the operation (Figure 28).

Table 6. Surgical treatment of the filler complication

————————————————————–

Removal ; Squeeze, En-block

External skin excision

Skin irregularity; to use soft tissue such as Dermofat, Perichondrium, Fascia, Alloderm etc

Local flap ; Bi-lobed flap, Rhomboid flap, Subnasale flap, etc

Total reconstruction of defects

—————————————————————

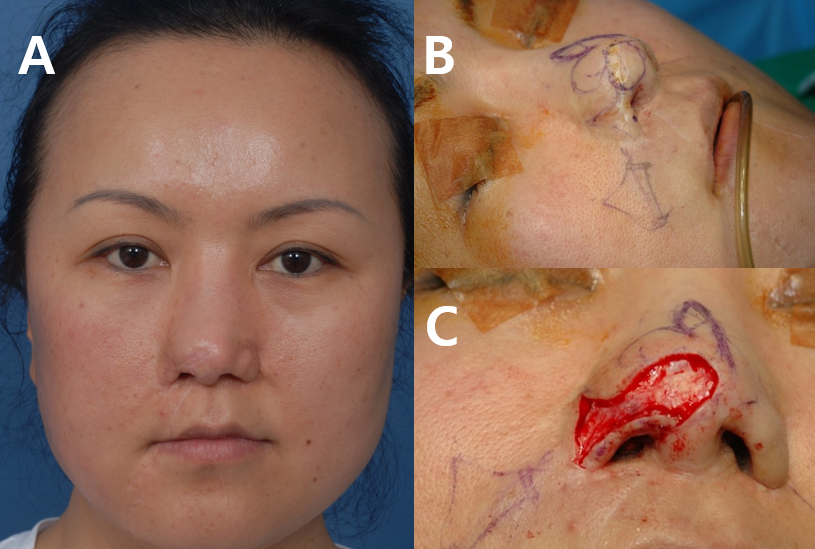

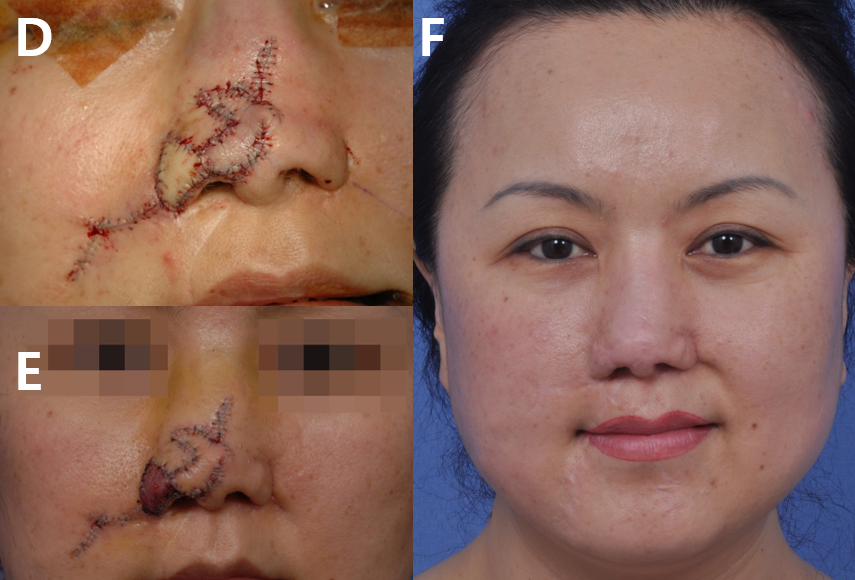

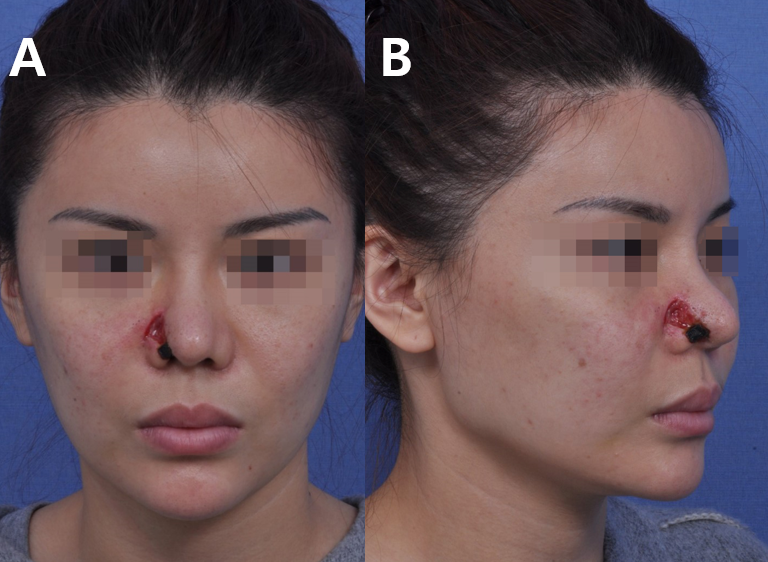

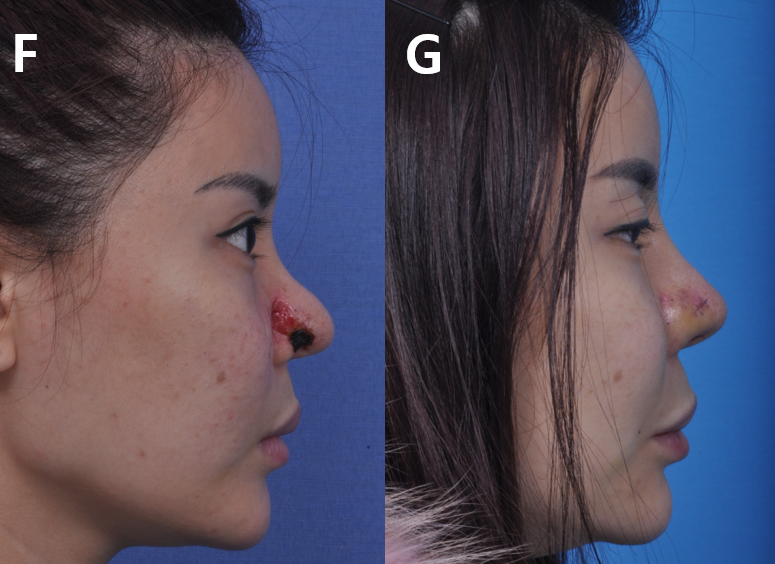

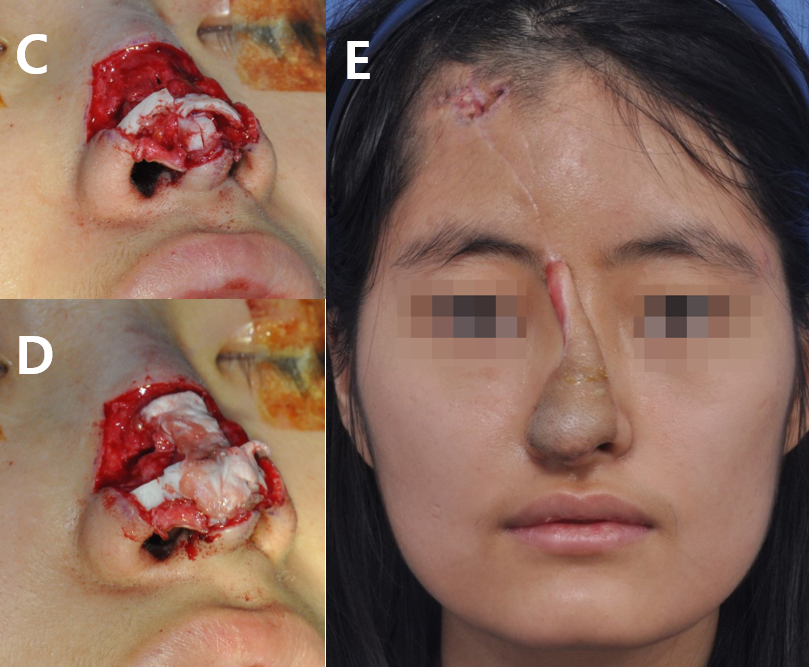

If necrosis has occurred with subsequent damage to the skin, then nasal reconstruction using a local flap or free graft is required. In general, reconstruction should be done several months after the necrosis has occurred, when the surrounding tissues are stable and the deformed area becomes smaller due to scar contracture (Figure 29). There are exceptions however; sometimes the reconstructive rhinoplasty can be performed right after the necrosis occurred, before the deformation worsens (Figure 30). It is our experience that during the acute period, if the vascular compromise is of the nonarterial type, often the skin surrounding the necrotic area is of poor quality; therefore immediate reconstruction is not advised. However, if it is the arterial embolism type, the area of damage is well demarcated and the adjacent tissue is generally healthy and viable. In the latter case, reconstruction in the more acute period can be considered.

Figure 28. The patient had liquid filler injection on the nose (A). We removed the filler material during the operation (B, C). The postoperative photograph shows that this region is well healed after surgery (D).

Figure 29. There is deformation of the skin on the nasal tip and right side of the ala after filler necrosis (A). A bilobed flap and nasolabial flap were used for the reconstruction (B, C, D, E). Postoperative photograph demonstrating that the area is well healed after surgery (F).

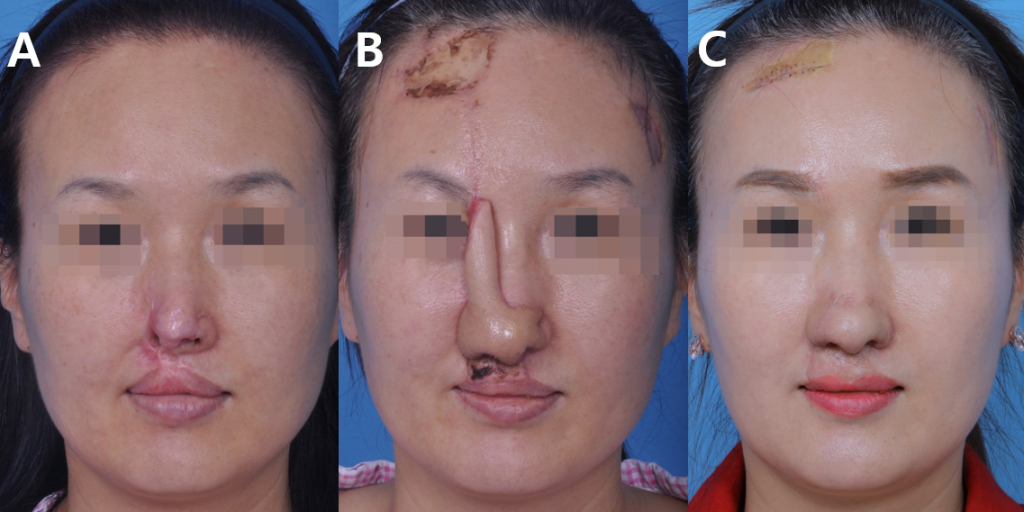

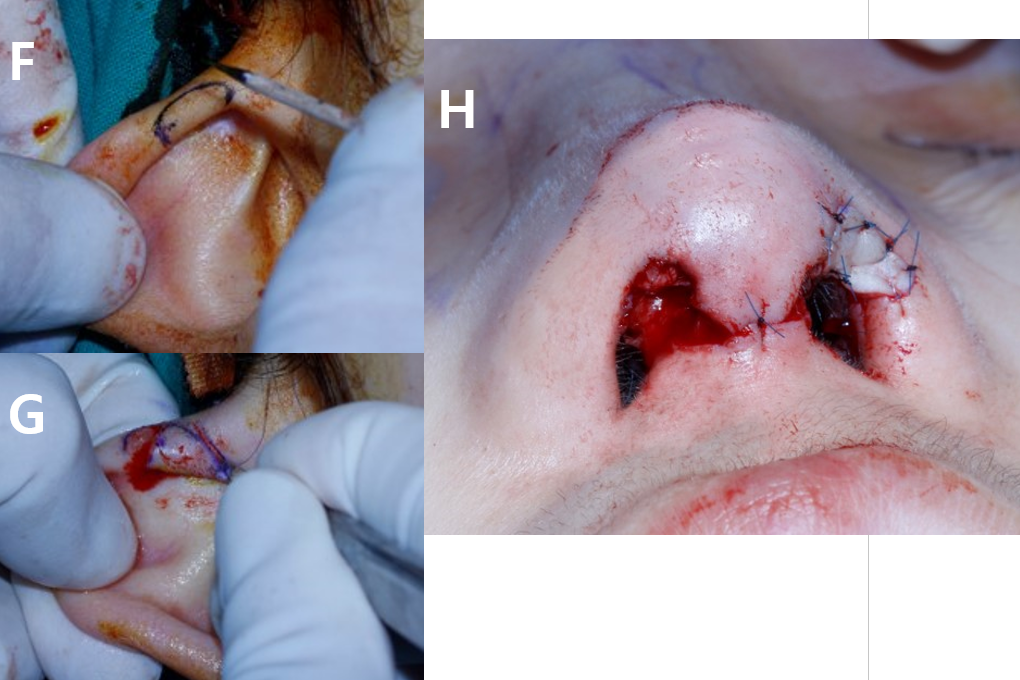

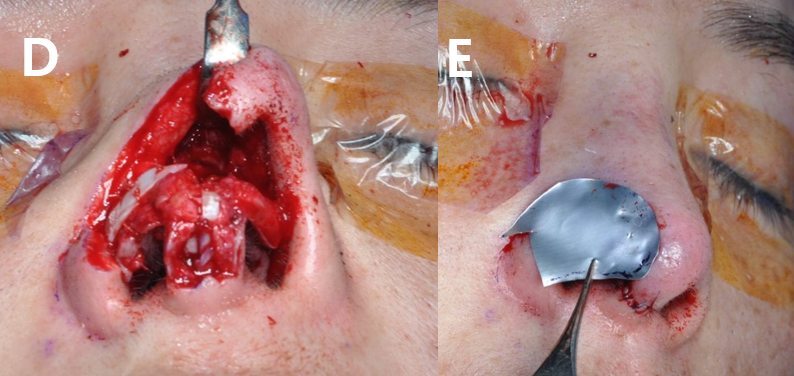

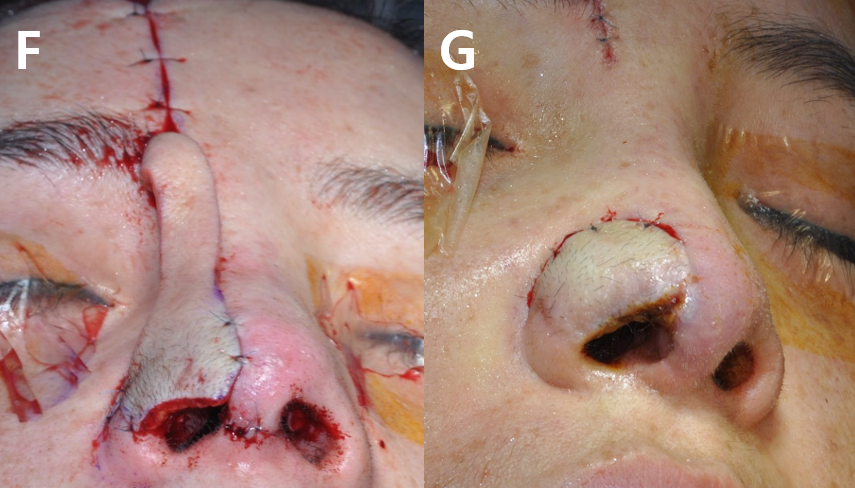

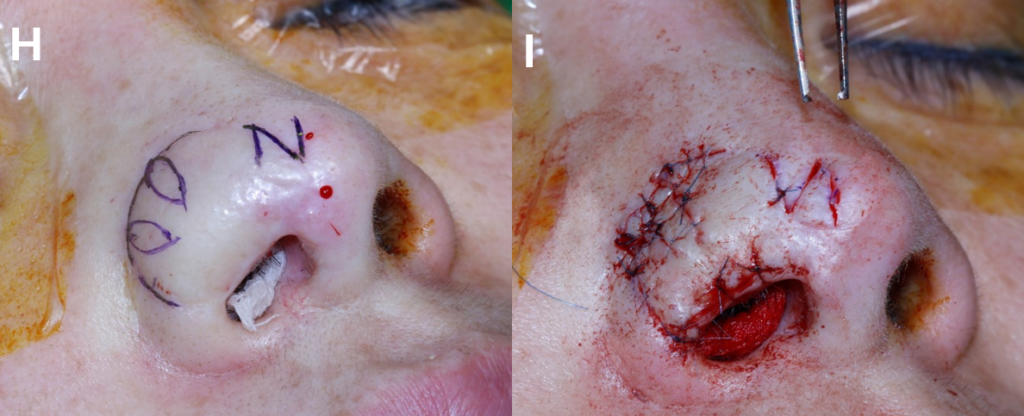

Figure 30. We performed reconstructive rhinoplasty using a forehead flap during the acute stage, only 2 weeks after arterial embolization and necrosis (A, B). This is an intra-operative photograph of the first-stage surgery using forehead flap (C) and at the second stage, before the pedicle division (D). These are pre and post-operative photographs (E, F, G, H, I).

3) Reconstructive rhinoplasty depending on the size and location

The types of flaps used for reconstructive rhinoplasty depend on the location and the size of the lesion.

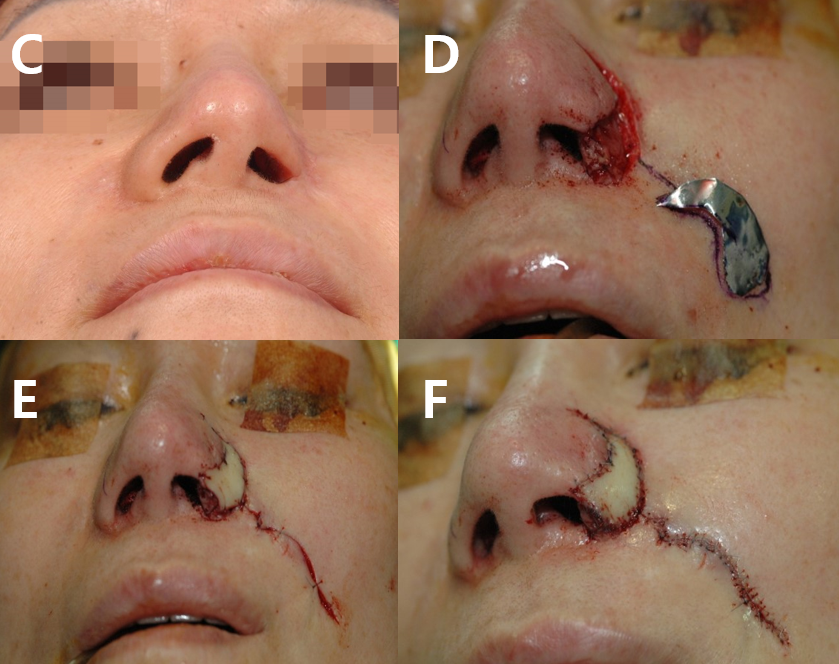

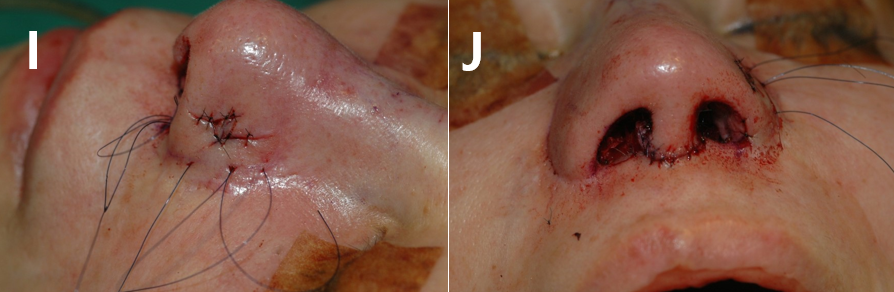

In the case of small defects of the alar unit or columella, skin graft, composite graft or local flap can be used for the repair (Figure 31,32). Local flap selection varies depending on the size and location of the defect after the necrosis. Options include rhomboid flaps, bilobed flaps, subnasale flaps etc.

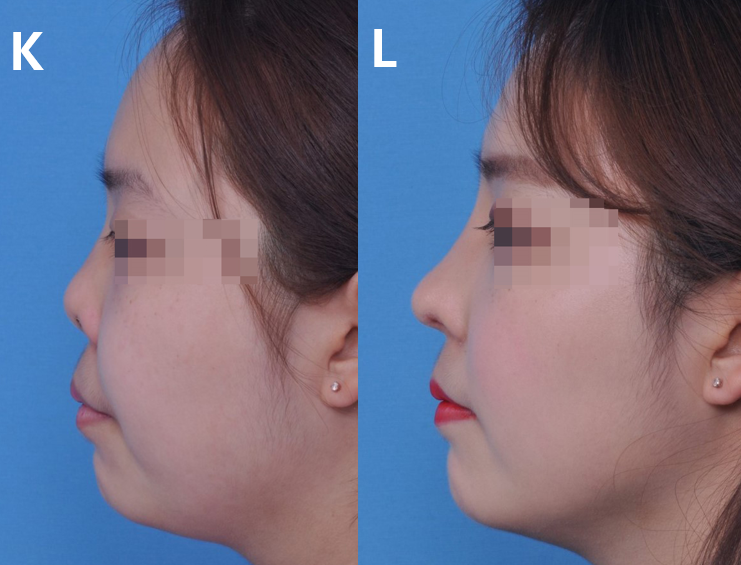

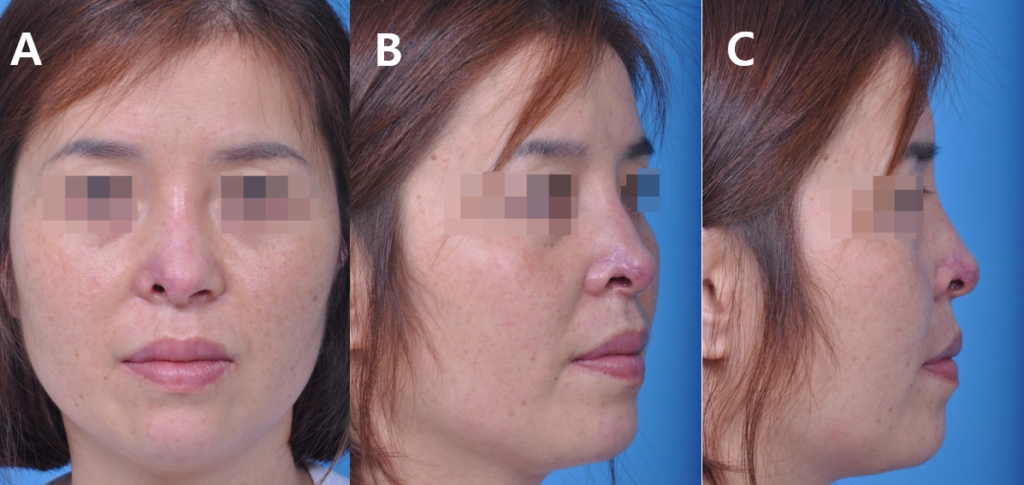

However for the majority of our reconstructive rhinoplasty cases, we prefer to use the forehead flap and nasolabial flap. The latter is useful in older patients with a deeper nasolabial fold. However, recently we have shifted our general preference to the forehead flap, especially for the young patient, because of the almost invisible donor site scar and favorable aesthetic result. Melolabial flaps require a two-stage operation with subcutaneous pedicled flaps (Figure 33). However, in general, reconstructive rhinoplasty usually requires a three-stage operation, and on top of this one or two additional surgeries may be necessary in order to correct scars and minor deformities (Figure 34).

If the defect involved the lip or the philtrum, it is recommended that the surgeon consider reconstructing the deformed skin in these areas simultaneously with the nasal reconstruction (Figure 35).

Figure 31. The patient had the defect on the left alar rim after filler injection (A,B). We performed tip projection and dorsal augmentation using costal cartilage (C, D, E), and used composite graft to cover the defect on the left nasal rim area (F, G, H). These are pre and post-operative photographs (E, F, G, H, I).

Figure 32. Reconstructive rhinoplasty after filler necrosis (A, B). The first stage operation was performed using a forehead flap (C, D). This picture was taken prior to the second stage operation for pedicle division (E). These are pre and post-operative photographs (F, G, H, I).

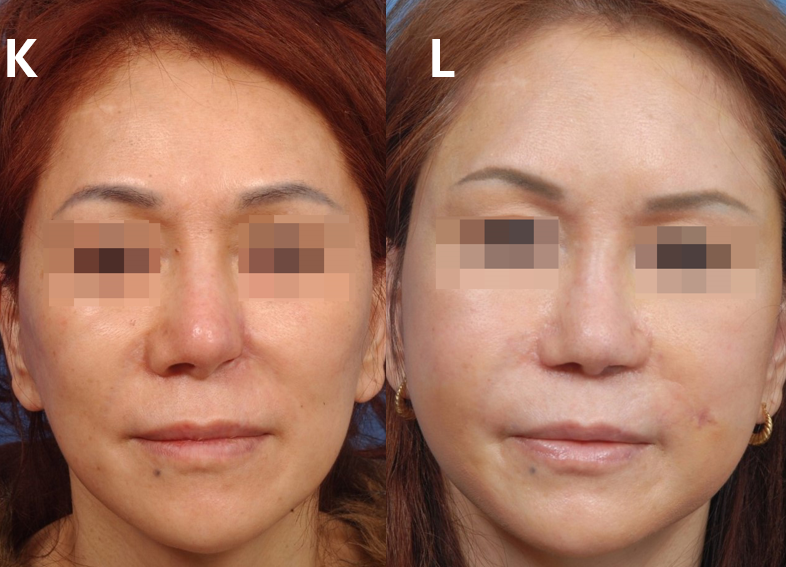

Figure 33. Necrosis of the left ala secondary to vascular compromise after filler injection (A, B, C). We used a subcutaneous pedicled melolabial flap to reconstruct the ala unit defect, which does not require pedicle division (D, E, F). These are post-operative photographs of the first stage operation, which needed further debulking surgery (G, H), and intra-operative photographs of the second stage operation (I, J). Pre and post-operative photographs (K, L) of the final result.

Figure 34. Reconstructive rhinoplasty usually requires a three stage operation. The necrosis seen on the right ala occurred following filler injection (A, B, C). We recreated the framework and reconstructed the defect using forehead flap; photo taken during the first stage operation (D, E, F). We divided the pedicle during the second stage operation (G), and finally we performed a third stage operation for debulking and refining the shape (H, I). These are pre and post-operative photographs: frontal view (J, K), oblique view (L, M, N), profile view (O, P, Q), and basal view (R, S).

Figure 35. There is necrosis on the nose and the philtrum after filler injection on the nasolabial angle area (A). This is a post-operative photograph after the first stage operation, including reconstruction of the philtrum area (B), and following the third stage operation (C).

7. Conclusion

Filler rejuvenation is a commonly performed cosmetic procedure because of its relative safety, minimal invasiveness and short recovery time. Nevertheless the potential complications resulting from filler injection can have devastating consequences due to vascular compromise leading to local tissue necrosis or blindness. To prevent this, the clinician must have a good grasp of the anatomy of the injection site and knowledge of the properties of the filler materials that they plan to use. When injecting the filler on the nose or around the nose, the clinician should be particularly careful because of the limited number of vessels in this site and the potential absence of collateral circulation due to anatomical variations. Injection into the correct plane, using safe equipment and techniques are key. After the injection, the patient should be monitored for blanching, pain, or heating sensation. The patient should also be instructed to contact the clinic without delay if these symptoms should occur after they return home. Furthermore, we recommend that absorbable fillers rather than non-absorbable fillers be used, because of the former’s reversibility by hyaluronidase. Additionally, non-absorbable fillers have the potential to develop delayed complications, such as granuloma and migration after an extended period of time and their removal can be challenging with the risk of skin irregularity, perforation and necrosis.

To conclude, fillers are a useful adjunct in facial rejuvenation. However they are not without risks and should be used judiciously to maximize their effect and safety. Should complications occur, expedient early management is critical to mitigate any potential damage from vascular compromise.

Reference

1. Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, Jones D. Avoiding and Treating Blindness From Fillers: A Review of the World Literature. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(10):1097-1117.

2. Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of Hyaluronic Acid Filler-Induced Impending Necrosis With Hyaluronidase: Consensus Recommendations. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35(7):844-849.

3. Inoue K, Sato K, Matsumoto D, Gonda K, Yoshimura K. Arterial embolization and skin necrosis of the nasal ala following injection of dermal fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121:127e-128e.

4. Jung DH, Hyun SM, Gan KG. Clinical appearance of vascular compromis after filler injection. J Cosmet Med 2019;3(1):19-24

5. Jung DH, Kim HJ, Koh KS, Oh CS, Kim KS, Yoon JH, et al. Arterial supply of the nasal tip in Asians. Laryngoscope 2000;110:308-11.

6. Kim SN, Byun DS, Park JH, et al. Panophthalmoplegia and Vision loss after cosmetic nasal dorsum injection. J Clin Neurosci 2014;21(4):678-80.

7. Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, etal. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;129(4):995-1012.

8. Ledon JA, Savas JA, Yang S, et al.inflammatory nodules following soft tissue filler use: a review of causative agents, pathology and treatment options. A m J Clin Dermatol 2013;14(5):401-11

9. Moon HJ. Injection rhinoplasty using filler. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2018;26:323-30.

10. Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, Jones D. Avoiding and Treating Blindness From Fillers: A Review of the World Literature. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(10):1097-1117.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Figure 25

Figure 26

Figure 27

Figure 28

Figure 29

Figure 30

Figure 31

Figure 32

Figure 33

Figure 34

Figure 35