INTRODUCTION

Rhinoplasty in children and adolescents remains a topic of controversy. In children, both open- and endonasal approaches can be used to reallocate or reconstruct the nasal skeleton after trauma, infection or in congenital deformities. Alternatively these approaches can be used as a route to remove malignant or benign pathology. The cartilaginous nasal septum is a dominant growth center of the nose. Resection or detachment of specific cartilaginous or bony structures of the nasal skeleton carries the risk of growth disturbances of both the nose and maxilla. Rhinoplastic techniques have changed over the years and became more conservative towards tissue reorientation and augmentation rather than resection and reduction. Nevertheless, surgical techniques that are considered to be safe in adults might have a negative effect on the outgrowth of the nasal skeleton in children leading to underdevelopment and progressive malformations. Therefore, rhinoplasty in children is fundamentally different from rhinoplasty in adults. This chapter covers the anatomy and development of the nasal skeleton from newborns to adulthood, the indications and goals for septorhinoplasty in children and guidelines for rhinoplasty to avoid sequelae and growth disturbances.

ANATOMY AND POSTNATAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE NASAL SKELETON

Anatomy

Compared to the nose of an adult, the nose of a baby is smaller with a shorter nasal dorsum, less projection of the nasal tip and columella, rounder nostrils and a larger nasolabial angle (1,2). The overlying soft tissue envelope has a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. The nasal skeleton of an infant is mainly cartilaginous. The main supporting mechanism of the nose is the nasal septum which forms a T-bar-shaped structure with the upper laterals. Like in adults, these upper lateral cartilages extend cephalically underneath the nasal bones, but in children they extend further to reach the anterior skull base (3,4). The nasal septum is initially cartilaginous and develops due to the formation of new cartilage. Within the first postnatal year an endochondral ossification process starts in the region of the anterior skull base with the formation of the perpendicular plate in ventro-caudal direction. In a later stage the perpendicular plate extends due to progressive ossification of nasal septal cartilage (5,6). Due to this ossification process most of the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum loses contact with the sphenoid. In adults, only a small remnant of septal cartilage (the “sphenoid tail”) can be found between the cartilaginous nasal septum and the sphenoid separating the perpendicular plate from the vomer. The formation of the vomer is the result of extracartilaginous ossification. During childhood and adolescence the typical “baby face” disappears due to the more rapidly and longer lasting development of the nose, maxilla and mandible, compared to the brain skull. Nasal growth was observed to be completed earlier in females (16 to 18 years) compared to males (18-20 years) (7).

Growth and development of the nasal septum

There are two significant nasal growth spurts, the first two postnatal years and during puberty when the nose grows faster compared to other periods in life. The growing cartilaginous nasal septum has been demonstrated to be an organizer of midfacial growth. The cartilaginous part of the nasal septum is not a straight piece of cartilage but has a 3D organization with two thicker areas with different mitotic activity and histological maturation (8). These ticker areas, or growth zones, are approximately 3 mm thick whereas the thinner area between these zones has a transverse diameter of approximately 0.4 mm. Both zones extend from the sphenoid. The “sphenodorsal” zone is located between the sphenoid and the nasal dorsum and appears to be primarily responsible for the normal increase in length and height of the nasal dorsum (9). The “sphenospinal” zone is located between the sphenoid and the anterior nasal spine and is the driving force in forward outgrowth of the (pre)maxilla region. The thinner area of septal cartilage does not influence nasal development and facial growth (9). Both clinical observations (10-15) and experimental studies (16-23) have shown that destruction of the growth zones during childhood result in underdevelopment of both the nose and the maxilla. Destruction of these zones can be the result of surgery or trauma but septal hematomas and nasal septal abscess formation are more common causes. The effect of destruction of the nasal septum on midfacial growth was age related; in younger children the outcome was more severe compared with older children (10-11). A young child with complete destruction of the nasal septum will end up with an underdeveloped saddle nose deformity with columellar retraction, an over-rotation of the nasal tip and a retroposition of the midface.

INDICATIONS FOR RHINOPLASTY IN CHILDREN

The aim to perform rhinoplasty in children is to restore the anatomy and function or to promote normal development and outgrowth of the nose. For every indication the expected benefits of intervention should be weighed against the possible adverse outcomes on nasal and midfacial growth. In the ideal situation surgery should be postponed till after the pubertal growth spurt. However, there are distinct indications for immediate intervention. Apart from malignancies, these indications include destruction of the nasal skeleton due to nasal septal abscesses or severe nasal trauma. In these cases the skeleton should be reconstructed in order to avoid growth inhibition. Other indications for surgical intervention and not to postpone surgery till after the growth spurt are situations in which the nasal breathing is severely impaired or the deformity of the nose causes psychological problems, like in the cleft lip patient or progressive distortion of the nose.

Septal abscess

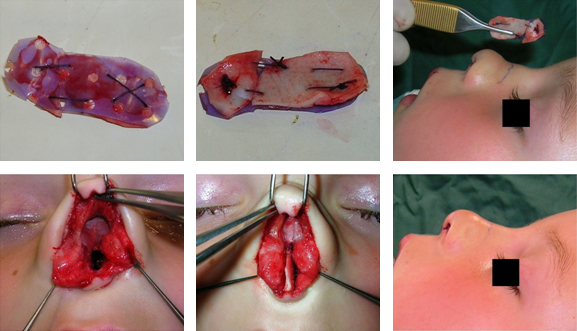

In the vast majority of cases a nasal septal abscess in childhood is caused by nasal trauma. In first instance a hematoma will develop between the cartilage surface and the mucoperichondrium that can result in insufficient oxygenation and sterile necrosis (24). The process of necrosis can be intensified due to liquification by collagenases produced by microorganisms that contaminate the hematoma into an abscess (25-30). Complications like thrombosis of the cavernous sinus or brain abscesses are rare and often associated with delayed diagnosis and management (31). The cartilaginous part of the nasal septum will be destructed within a couple of days. First the thinner parts will be destructed but in a later stage also the thicker areas or septal growth zones. Without proper surgical treatment destruction of the cartilaginous septum will result in an underdeveloped and overrotated saddle nose deformity with retraction of the columella and a retroposition of the midface (13). Therefore, reconstruction of partial or completely destructed septal cartilage in which the growth zones are involved, is essential for the normal development of the nose and the maxilla. As reconstruction material autologous cartilage grafts from the auricle or rib are the implant materials of choice in line with current medical practice (13). The grafts can be affixed to polydioxanone (PDS) foil (0.15x50x40 mm, Ethicon) in order to ensure good tissue to tissue approximation of the individual grafts into one perfectly fitting implant (Figure 1 and 2). Systemic antibiotics should be administered for one week. Clinical observations have shown that this technique showed a normal development of the nose during follow-up, without expected esthetic problems (12,13).

|

| Figure 1. Peroperative pictures from a three-year-old girl with complete destruction of the cartilaginous nasal septum due to a nasal septal abscess. Top: auricular cartilage grafts were affixed to PDS foil into one precisely fitting implant. Down L to R: the septum is destructed completely. The implant precisely fits between the perpendicular plate, the upper lateral cartilages and the premaxilla in between the intact mucoperichondrium layers and fixed with mattress sutures.. End result, the reconstrcuted nasal septum provides sufficient support to the upper laterals to avoid a saddle of the nasal dorsum. |

|

| Figure 2. Pre- and postoperative photo’s from the same girl as Figure 1. Left: preoperative two weeks after nasal trauma and a nasal septal hematoma that developed into a nasal abscess. There were already signs of a mild saddle nose deformity, in order to avoid growth inhibition of the nose and the maxilla the nasal septum was reconstrcuted using autologous auricular cartilage grafts. Middle: one year after surgery. Right: two years after surgery, there are no signs of a saddle nose deformity or severe retraction of the columella. The development of the nose and maxilla is normal. |

Dermoid cyst

Dermoid cysts are slow growing masses over the dorsum of the nose that may contain skin, hair follicles, sweat- or sebaceous glands. Dermoids may become locally infected or drain through the sinus opening. The origin of dermoids may be the result of faulty closure of the fonticulus frontalis which permits dermal elements to invaginate between the developing nasal bones and cartilage. Or they may the result of dura that remains in the prenasal space instead of being retracted through the foramen caecum. The lesions can be localized on the nasal dorsum anywhere along the midline from the nasal tip to the glabella, in the nasal septum or pulled intracranially. In all cases they can be left attached to the CNS by a fibrous stalk (32-34). Therefore, surgical intervention should be postponed after radiologic evaluation with MRI and or CT in order to examine possible anterior skull base defects or CNS connections. An external approach rhinoplasty provides a wide exposure for excision of the tract and in case needed also to the cribiform plate (35-37) (Figure 3). Apart from excising the sinus opening the broken midcolumellar incision gives a superior cosmetic result compared with skin incisions like paracanthal incisions over the dorsum of the nose, without compromising the recurrence rate (38). Surgical excision prevents expansion, infection and destruction of adjacent tissues. In order to avoid recurrence it is important to leave no remnants, the use of methylene blue might be helpful to follow the tract. The bony-cartilaginous skeleton is left intact thus no growth disturbance is observed (37)

|

| Figure 3. Left: preoperative picture from a young boy with a dermoid cyst located in the nasofrontal angle. Middle top: an MRI scan showed no connection with the CNS. Middle middle: peroperative photo, the cyst was removed using an external approach rhinoplasty, this approach provides excellent exposure without the need for additional incisions. Middle down: The removed cyst. Right: postoperative photo one year after surgery. |

Severe external deformity with psychological impact

Human society has a long history of stigmatizing facial disfigurement (39). A nasal deformity presents a serious psychological and social challenge to children, they have to cope with an appearance that is different and that can not be concealed, which is subject to social stigma. Modern day pressures of increasing use of plastic surgery and a culture that is focussed on appearance combine the pressure on those who look different (40). Patients with facial disfiguration or severe nasal deformities often report increased social anxiety, feelings of low self esteem and self worth and depression. The response of the general population ranges from intrusive staring through aggression to pity and disgust, in any combination (41). The degree of deformity however, does show a linear relation with the degree of experienced distress. Form a psychological point of view similar to severe protruding ears, in the ideal situation surgery is performed at pre-school ages in which children do not note the deformity (40,42). The decision to perform rhinoplasty however should include the degree of the deformity, the psychological effect on the child and the impact on nasal growth and development (Figure 4.)

|

| Figure 4. Pre- and postoperative pictures. Top: preoperative views from a 15 year old girl with a severe nasal deformity including a deviated and drooping nasal tip, a thin and underdeveloped ala on the left side and a deep nasofrontal angle. Down: postoperative pictures. The nose was reconstructed using septal-, auricular- and homologous irradiated rib grafts. Augmentation of the nasofrontal agle and left ala, upward rotation and deprojection of the nasal tip. |

Cleft lip nose

The traditional approach in the management of the cleft lip includes a single stage lip repair at 3 months of age, palatoplasty at approximately 1 year of age, alveolar bone grafting at 9 to 11 years and definitive rhinoplasty after the puberty growth spurt (43). The timing of rhinoplasty remains a topic of debate. Primary cleft rhinoplasty can take place at the time of lip closure (44). In this procedure the floor of the nose is closed whereas the alar base and lower lateral cartilages are repositioned in order to create symmetry and to improve tip definition. Growth inhibition is not expected since the nasal skeleton is left intact, only reallocation of soft tissues and lower lateral cartilages is performed. For older children and teenagers with a cleft lip nose, the deformity is a heavy psychological burden. Therefore, secondary rhinoplasty is often performed before the end of the puberty growth spurt. In the majority of cases, the open approach is used in secondary cleft rhinoplasty; this approach allows optimal visualization of the complex anatomy and adequate exposure for reconstruction of the deformities. In most cases a transcolumellar inverted-V incision is used but a V-Y procedure may be an alternative to lengthen a short columella. In unilateral clefts, inadequate skeletal support on the cleft side gives rise to the typical asymmetries (45). The caudal part of the nasal septum is deviated to the non-cleft side (area I and II) whereas the rest of the nasal septum is typically deviated to the cleft side. The ala is flattened on the cleft side with lack of nasal tip projection. Secondary cleft lip rhinoplasty includes septoplasty, with repositioning of the septum and anterior nasal spine in the midline. Realignment of the cleft side lower lateral cartilage (LLC) can be reached using lateral crural steal, a columellar strut graft and reinforcement of the alar sidewall using an alar batten graft. Alternatively, in case of a strong concave lateral crus on the cleft side, the crus can be flipped around to create a convex shape of the cartilage. Symmetry of the nasal tip is created using trans- and interdomal suturing techniques and in case required a shield- or cap graft to improve nasal tip projection. The alar base is augmented on the cleft side using cartilage grafts and repositioned using a (modified) Z-plasty to create symmetry. If there is residual alar hooding, symmetry of the alar rim can be accomplished by suturing the LLC to the upper lateral cartilage or by removing a small wedge of excessive skin tissue at the side of the marginal incision, both procedures will reposition the alar rim more superiorly. The upper two thirds of the nose often require osteotomies of the bony pyramid and uni- or bilateral placement of spreader grafts.

Nasal trauma

Trauma of the nose can result in dislocation- or fractures of the cartilaginous and bony skeleton or in the formation of a hematoma. Correct diagnosis in small children can be complicated due to oedema of the surrounding soft tissues and the small anatomical dimensions. Re-examination or inspection in general anaesthesia after a few days might than be helpful. Septal- and dorsal hematomas however should be ruled out prompt in order to avoid iatrogenic delay and destruction of septal- and/or upper lateral cartilages. A dorsal hematoma can be diagnosed as a swollen bluish hue at the site of the internal nasal valve or the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilages. Both a dorsal- and septal hematoma should be evacuated (puncture or drain) as soon as possible to avoid abscess formation and subsequently the destruction of cartilage. It is recommended to do this in general anaesthesia and to evaluate the condition of the nasal septum carefully. In case cartilage is already destructed an attempt should be made for a direct reconstruction using autologous cartilage grafts. Systemic antibiotics, nasal packing and/or septal mattress sutures are recommended to avoid dead space the recurrence of hematoma or abscess. In case the nasal skeleton is fractured or dislocated examination and surgical intervention should take place in general anaesthesia. Fractures of the nasal bones can be repositioned without the chance of disturbing the normal development of the nose. An attempt can be made to reposition fractures of the cartilaginous nasal septum by mobilizing the nasal dorsum upward thereby elevating the nasal septum in the midline. However, if this is not possible an open approach rhinoplasty or a hemitransfixion may be required to reconstruct the fractured nasal septum with or without the use of Polydioxanone (PDS) foil.

Severe Impaired Nasal Breathing

Impaired nasal breathing in childhood may be the result of severe septal deformities like septal deviations. Other causes like choanal atresia, benign- or malignant tumours of the nose or nasopharnyx, juvenile polyposis nasi, allergy or hypertrophy of the adenoid must be ruled out before surgical intervention of the nasal septum is considered. Decongestion of the nasal mucosa, nasendoscopy and imaging might be mandatory for correct assessment and diagnosis. Severe septal deviations are likely to worsen with growth and may cause progressive distortion- and growth inhibition of the nose and midface. Septoplasty restores the anatomy and function and may promote normal development and outgrowth of the nose. Conversely, septoplasty may cause growth inhibition. This dilemma should be weighted and discussed with the patient and parents. In case of less evident deformities a “wait and see” policy might be a good alternative. Follow-up will give the opportunity to evaluate the development of the nose and the functional complaints of the child. If the decision for surgical intervention is made, it should be conservative according to the guidelines in this chapter. Particularly in younger children the external approach might be helpful since the small nostrils may diminish the visualization of the operative field in endonasal approaches.

GUIDELINES FOR RHINOPLASTY IN CHILDREN

Surgical techniques that are considered safe and effective in adults can have a negative outcome on growth, function and aesthetics in children. Literature on the long-term effects of rhinoplasty in young children however, is fragmentary and often incomplete (9). Based on clinical and experimental observations guidelines were developed for conservative septorhinoplasty in children (3,4,46-59). Following these practical surgical guidelines the risk of growth inhibition or the introduction of progressive malformations are rare but patients and parents should be informed that late results can not be predicted and revision surgery should be discussed. For this reason, both patient and parents should also be informed about continuing follow-up till after the adolescence growth spurt. As in adult rhinoplasty, standardized pre- and postoperative photography should be performed together meticulous assessment and documentation of the preoperative anatomical condition and the clinical findings during surgery.

Guidelines for rhinoplasty in children

In general, elevation of the mucoperichondrium of the nasal septum and denudation of the soft tissue envelope from the rest of the nasal skeleton can be performed safe as long as the skeleton is left intact (60). Both endonasal approaches and the open approach trough a transcolumellar incision may be used, avoid cartilage-splitting techniques. Elevation and tunnelling of the mucosa on one or both sides does not interfere with normal growth (61). Care should be taken to elevate the mucosa from the nasal floor to damage the incisive nerves. Once the septal mucosa is elevated and the cartilaginous- and bony septum is exposed, one should be as conservative as possible with incisions, scoring and chondrotomies. Avoid incisions through-, or partial removal of, the sphenodorsal zone. This will result in growth inhibition of the nasal septum and the nasal dorsum. Incisions through-, or removal of, the sphenospinal zone will result in underdevelopment of the nasal spine and the maxilla (3,47,61,62). Incisions and or scoring of deviated areas of cartilage do not achieve predictable results and thus should be prevented. Incisions through-, or removal of the thinner central part of the cartilaginous nasal septum does not inhibit growth of the septum (58). Chondrotomies, like a posterior chondrotomy, in which the cartilaginous septum is separated from the perpendicular plate, should be avoided because this will inhibit further growth of the nasal septum and dorsum (61). The septospinal ligament, the connection between the cartilaginous septum to the premaxilla, should also not be transacted as it anchors the septum in the midline and plays a role in the forward outgrowth of the maxilla (9). Bony deviations of the premaxilla and vomer on the other hand, can be mobilized and removed without disturbing the normal outgrowth of the nose (61). In case of nasal trauma, defects and fractures of the septum should be identified. Mobilize deviated or overlapping fragments of cartilage and adjust form and size of the fragments in order to reconstruct a straight septum in the midline. Polydioxanone (PDS) foil (0.15 mm) may be used as a temporary carrier to support and stabilize the fragments or where the septum needs support (12,13,63). For defects that cannot be reconstructed with septal cartilage, autologous cartilage from the auricle or rib should be used (12,13). Homologous- or biomaterials are not capable of growth and may induce growth inhibition when implanted in the growing septum (13). Leftover cartilage should be crushed gently and placed back into cartilaginous septal defects to allow restrengthening and to avoid a septal perforation (51). The formation of a hematoma between the septum and the mucoperichondrium should be avoided by using mattress sutures to ensure good tissue approximation and thus to avoid dead-space. Osteotomies of the bony pyramid can be performed without inhibition of growth. Alar base wedge resection, -repositioning and –augmentation as used in the cleft lip patient, will not interfere with nasal growth and development. Avoid separating the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal septum; this bears the risk of outgrowth of the septum anterior of the upper laterals resulting in irregularities of the nasal dorsum (51). Disturbing the T-bar structure of the cartilaginous vault, like in hump reduction and the use of spreader grafts should therefore be postponed till after the puberty growth spurt. Nasal grafts, other than in the reconstruction of the growing nasal septum, may lead to unpredictable results and thus should be prevented.

REFERENCES

- Potsic WP, Cotton RT, Handler SD. Nasal Deformity. In: Surgical Pediatric Otolaryngology. New York: Thieme medical publishers; 1997:168-180

- Stool S, Marasovich WA. Postnatal craniofacial growth and development. In: Bluestone CD, Stool SE, eds. Pediatric Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:17-31

- Loosen van J, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, Verwoerd CDA. The nasal septal cartilage in the newborn. Rhinology 1988;26:161-165

- Poublon RML, Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Anatomy of the upper lateral cartilages in the human newborn. Rhinology 1990;28:41-46

- Schultz-Coulon HJ, Eckermeier L. Zum postnatalen Wachstum der nasenscheide-wand. Acta Otolaryngol 1976;82:131-142

- Verwoerd CDA, van Loosen J, Schutte HE, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, van Velzen D. Surgical aspects of the anatomy of the vomer in children and adults. Rhinology 1989;9:87-96

- Graber TM. Postnatal development of cranial, facial and oral structures: the dynamics of facial growth. In: Orthodontics: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1966:69-78

- Meeuwis J, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, Verwoerd CDA. Normal and abnormal nasal growth after partial submucous resection of the cartilaginous septum. Acta Otolaryngol 1993;113:379-382

- Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Rhinosurgery in children: Basic Concepts. Facial Plastic Surgery 2007;23:219-230

- Pirsig W. Morphological aspects of the injured septum in children. Rhinology 1979;17:65-76

- Pirsig W. The influence of trauma on the growing nose. In: Mladina R, passali D, eds. Pediatric Rhinology. Siena Tipografia Sense; 2000:145-159

- Menger DJ, Tabink I, Nolst Trenite GJ. Treatment of septal hematomas and abscesses in children. Facial Plastic Surgery 2007;23:239-243

- Menger DJ, Tabink I, Nolst Trenite GJ. Nasal septal abscess in children, reconstruction with autologous cartilage grafts on Polydioxanone Plate. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008;134(8):1-6

- Hayton ChH. An investigation into the results of the submucous resection of the septum in children. J Laryng 1916;31:132-138

- Ombredanne M. Les deviations traumatiques de la cloison chez l’enfant avec obstruction nasale. Traitement chirugical et resultants eloignes. Arch Fr Pediatr 1942;I:20:378

- Verwoerd CD, Urbanus NA, Nijdam DC. The effects of septal surgery on the growth of nose and maxilla. Rhinology 1979;XVII:53-63

- Sarnat BG, Wexler MR. The snout after resection of nasal septum in adult rabbits. Arch Otolaryngol 1967;86:463-466

- Freer OT. The correction of deflections of the nasal septum with a minimum of traumatism. J Am Med Assoc 1902;38:636-642

- Norgaard JO, Kvinnsland S. Influence of submucous septal resection on facial growth in the rat. Plast Reconstr Surg 1979;64:84-88

- Kvinnsland S. Partial resection of the cartilaginous nasal septum in rats: its influence on growth. Angle Orthod 1974;44:135-140

- Nolst Trenite GJ, Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Reimplantation of autologous septal cartilage in the growing nasal septum I. The influence of resection and reimplantation of septal cartilage upon nasal growth: an experimental study in growing rabbits. Rhinology 1987;25:225-236

- Killian G. Beitrage zur sub submukosen fensterresektion der nasenscheidewand. Passow U. Schaefer Teits. 1,1908:183-192

- Kremenak CR, Searls JC. Experimental manipulation of midfacial growth: a synthesis of five years of research at the Iowa Maxilla Facial Laboratory. J Dent Res 1971;50:1488-1491

- Fry HJ. The pathology and treatment of haematoma of the nasal septum. Br J Plast Surg. 1969;22(4):331-335

- Ambrus PS, Eavey RD, Baker AS, Wilson WR, Kelly JH. Management of nasal septal abscess. Laryngoscope 1981;91(4):575-582

- Ginsburg CM, Leach JL. Infected nasal septal hematoma. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1995;14(11):1012-1013

- Canty PA, Berkovitz RJ. Hematoma and abscess of the nasal septum in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head neck Surg 1996;122(12):1373-1376

- Da Silva M, Helman J, Eliachar I, Joachims HZ. Nasal septal abscess of dental origin. Arch Otolaryngol 1982;108(6):380-381

- McCaskey CH. Rhinogenic brain abscess. Laryngoscope 1951;18:460-467

- Eavey RD, malakzakeh MM, Wright HT Jr. Bacterial meningitis secondary to abscess of nasal septum. Pediatrics 1977;60(1):102-104

- Chukuezi AB. Nasal septal haematoma in Nigeria. J Laryngol Otol 1992;106(5):396-398

- Harley EH. Pediatric congenital nasal masses. Ear Nose Throat J 1991;70(1):28-32

- Hughes GB. Management of the congenital midline nasal mass: a review. Head Neck Surg 1980;2(3):222-233

- Jaffe BF. Classification and management of anomalies of the nose. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1981;14(4):989-1004

- Pashley NRT. Congenital anomalies of the nose. In Cummings CW and other , editors: otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surg, St louis, 1993, Mosby

- Hengerer AS. Congenital malformations of the nose and paranasal sinuses. In Bluestone CD, Stool SE, editors: Pediatric otolaryngology, vol 1, ed 3, Philadelphia, 1996, WB Saunders

- Dennis SCR, den Herder C, Shandilya M, Nolst Trenite GJ. Open rhinoplasty in children. Facial Plastic Surgery 2007;23(4):259-266

- Denoyelle F, Ducroz V, Roger G, Garabedian EN. Nasal dermoid cysts in children. Laryngoscope 1997;795-800

- Shaw WC. Folklore surrounding facial deformity and the origins of facial prejudice. Br J Plast Surg 1981;34:237-246

- Bradbury E. Meeting the psychological needs of patients with facial disfigurement. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2010.11.022

- Rumsey N, Harcourt D. The psychology of appearance. London: OUP;2005

- Spielmann PM, Harpur RH, Stewart KJ. Timing of otoplasty in children: what age? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2009;266:941-942

- Sykes JM, Jang YJ. Cleft lip Rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 2009;17:133-144

- Ness JA, Sykes JM. Basics of Millard rotation-ad-vancement technique for repair of the unilateral cleft lip deformity. Facial Plast Surg 1993;9:167-176

- Sykes JM, Senders CW. Surgical treatment of th unilateral cleft nasal deformity at the time of lip repair. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1995;3:69-77

- Shandilya M, Den Herder C, Dennis SCR, Nolst Trenite GJ. Padiatric rhinoplasty in an Academic setting. Facial Plast Surg 2007;23(4):245-257

- Loosen van J, Zanten van GA, Howard CV, Velzen D, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, Verwoerd CDA. Growth characteristics of the human nasal septum. Rhinology 1996;34:78-82

- Urbanus NAM. Schedelgroei na sluiting van lip-kaak-engehemeltespleten. Experimentele toetsing van de beginselen van enige chirurgische methoden bij het konijn. Thesis, University of Amsterdam: 1974

- Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Schedelgroei onder invloed van aangezichtsspleten. Een experimentele studie bij het konijn. Thesis, University of Amsterdam; 1974

- Mastenbroek GJ. De invloed van partiele resectie van het neustussenschot op de uitgroei van de bovenkaak en neus. Thesis, University of Amsterdam, 1978

- Nolst Trenite GJ. Postoperative care and complications. In; Nolst Trenite GJ, ed. Rhinoplasty, 3rd ed. Chapter 5. The hague: Kugler Publications; 2005;31-37

- Nolst Trenite GJ. Implantaten in een groeiend neustussenschot. Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam; 1984

- Nijdam DC. Schedelgroei na partiele submukeuze resectie van het neustussenschot. Thesis, University of Amsterdam; 1985

- Poublon RMC. The cartilaginous nasal dorsum and postnatal growth of the nose. Thesis. Erasmus University, Rotterdam; 1987

- Nolst Trenite GJ, Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Reimplantation of autologous septal cartilage in the growing nasal septum, II. Rhinology 1988;26:25-32

- Verwoerd CD, Meeuwis CA, van der Heul RO. Wound healing of the nasal septal perichondrium in young rabbits. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1990;52:180-186

- Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Anatomy and development of the nasal septum in relation to septal surgery in children. In: Sih T, Clement PAR, eds. Pediatric Nasal and sinus disorders. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2005:127-145

- Ten Koppel PG, van der Veen JM, Hein D, et al. Controlling incision-induced distortion of nasal septal cartilage: a model to predict the effect of scoring of rabbit septa. Plast reconstr Surg 2003;111:1948-1957

- Verwoerd-Verhoef HL, Meeuwis CA, van der Heul RO, Verwoerd CD. Histologic evaluation of crushed cartilage grafts in the growing nasal septum of young rabbits. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1991;53:305-309

- Triglia JM, Cannoni M, Pech A. Septorhinoplasty in children: benefits of the external approach. J Otolaryngol 1990;19:274-278

- Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Rhinosurgery in children, developmental and surgical aspects. In: Nolst Trenite GJ, ed. Rhinoplasty, 3rd ed. The Hague: Kluger Publications; 2005

- Velzen van D, Loosen J, Verwoerd CDA, Verwoerd-verhoef HL. Persistent pattern of variations in thickness of the human nasal septum: implications for stress and trauma as illustrated by a complex fracture in a 4-year old boy. Adv Otolaryngology 1997;51:46-50

- Boenisch M, Hajas T, Nolst Trenite GJ. Influence of Polydioxanone foil on growing septal cartilage after surgery in an animal model. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003;5:316-319