ABSTRACT:

With any rhinoplasty it is essential to take note of the relationship between the chin and nose. Often times chin modification can have significant results on the patients overall aesthetic facial proportions. This chapter describes chin analysis and modifications techniques, including alloplastic chin augmentation and sliding genioplasty.

INTRODUCTION

A comprehensive evaluation of the patient seeking a rhinoplasty should emphasize a balanced relationship between the nose and other facial features. This particularly relates to the chin and its posture within the lower one third of the face. Often patients see the dominant aesthetic feature more than they recognize smaller, retrusive facial elements. It is the job of the facial plastic surgeon to recognize and educate the patient with respect to these areas.

It is rare that the rhinoplasty patient takes into account their chin. Despite this, consideration of chin posture (projection, length, symmetry) and chin size is essential in achieving aesthetically pleasing results after rhinoplasty. For example, excessive reduction rhinoplasty in a patient with strong chin projection will highlight the prominence of the chin and make the nose appear abnormally small. Conversely, poor chin projection can make the nose appear abnormally large. Achieving a balanced proportion between the chin and nose is therefore fundamental to facial harmony

Various surgical techniques have been utilized to achieve facial harmony. The choice of technique depends on the overall size of the patient, their underlying skeletal framework, and desired goals. In some patients a chin implant or genioplasty will add to deficient framework. Gender differences may influence patient goals; for example, males with smaller chins generally desire more definition while females tend to want more refinement. In some patients, reduction of excessive submental soft tissue alone can add enough definition to the chin to achieve a desirable result.

Most times, however, the underlying framework of the chin is altered. The two basic techniques in chin augmentation surgery are:

- Placement of implant materials (alloplastic or autologous)

- Sliding genioplasty

Sliding genioplasty involves movement of the bony portion of the mandible without altering occlusion. Chin reduction can be accomplished by reduction genioplasty, however this will not be the focus of the chapter.

Studies have shown that up to 81% of patients undergoing rhinoplasty may benefit from chin augmentation to achieve the “ideal” chin-nose relationship. To achieve success with chin modification techniques, a thorough understanding of chin anatomy, facial proportion, and aesthetics are necessary. The surgical technique selected depends on the experience and skill of the surgeon and the desires of the patient.

ANATOMY

The chin itself consists of the bony mandible, mentalis muscle, depressor anguli oris muscles, and the soft tissue chin pad. The mentalis muscles are paired muscles that take origin on the bone just beneath the central incisors and insert at the skin of the chin pad. Contraction of these muscles aid in chin depression and dimpling and create a down-turned expression of the corners of the mouth. A “cleft chin” refers to a separation between the two heads of the mentalis muscles, which is quite difficult to create aesthetically.

The menton is the inferior most projection of the bony mandible and the pogonion is the anterior most projection. The relationship between the teeth, alveolus and mentum is an important consideration. If the teeth / alveolus are significantly posterior, as seen in class II occlusion, then the mental-labial sulcus will be deep and chin augmentation will create an aesthetically unpleasant contour despite appropriate projection.

AESTHETICS & PREOPERATIVE ANALYSIS

Analysis of the chin in the setting of rhinoplasty begins with first establishing the goals for the cosmetic outcome of the nose. Once these have been discussed, it is then possible to discuss how the desired nose relates to the remainder of the face. A thorough evaluation scheme is necessary for successful evaluation of the chin. Several methods have been described in the literature, which may require photos or cephalometric measurements. Analysis should include the anterior-posterior projection of the chin, the vertical height of the lower one third of the face, the relative proportion due to chin volume, recumbence of the lips, the depth of the labial-mental sulcus, width of the chin pad, presence of pre-jowl sulci, the position of the hyoid and submental soft tissue volume, dental occlusion, and asymmetries.

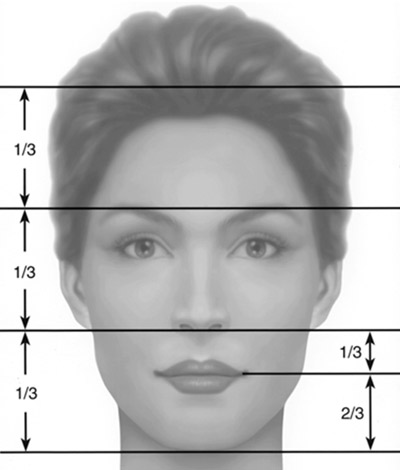

Facial analysis outlines favorable proportions in the vertical dimensions of the face (Figure 2). Traditionally the face has been divided into vertical thirds, with the lower third of the face extending from the subnasale to the menton. Further subdivisions have suggested that the distance from the subnasale to the stomion should be 1/3rd of the distance from the stomion to the menton. An increase in the vertical height of the chin is unattractive and can dominate other facial elements even if the chin point is under-projected.

Similarly a short vertical height causes the lower third to appear diminutive even if the AP position of the chin is ideal. This is often associated with increased lip recumbence and an associated deep labial-mental sulcus. In this circumstance, increasing the chin projection will generate an unpleasant result. Moreover asymmetries of the chin, as in other areas of the face, can be aesthetically distracting. The anterior-posterior posture of the chin point is but one feature that defines an attractive lower third of the face. The chin has a well- described effect on the perception of the attractiveness of the nose. In those circumstances when the vertical height of the chin is inappropriate, and significant asymmetries are present and lip recumbence is a meaningful consideration, then a genioplasty may be preferable to simple alloplastic chin augmentation.

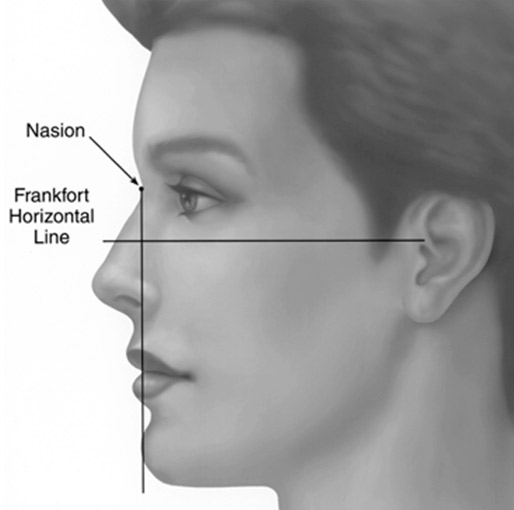

The actual position of the chin is dependent on the mandibular arch and its projection from the alveolus. According to Gonzalez-Ulloa, the chin lies in an ideal plane known as the zero meridian and is in the same plane as the nasion.(Figure 3)

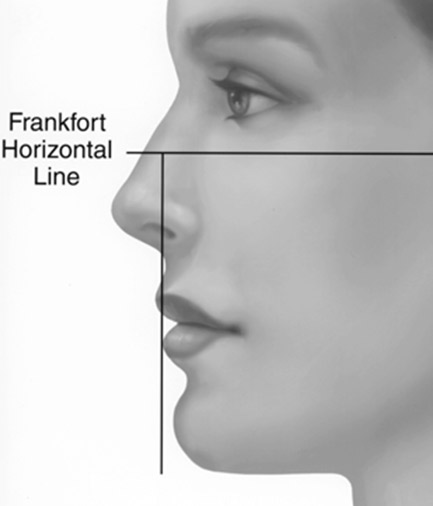

Others suggest that a vertical line dropped from the lower lip should approximate the chin in males and be 1-2 mm anterior to the chin in females (Figure 4). These ideal measurements are useful for analysis, but the ultimate position should be determined by the aesthetics of the individual patients’ face.

Occlusion plays an important role in the evaluation of the chin. True microgenia refers to a short chin in the sagittal and horizontal plane. In these cases the surgeon must consider whether an implant will suffice or if genioplasty is necessary. Both techniques address the anterior-posterior (AP) position of the chin, however genioplasty can also address the vertical height of the mandible as well as asymmetries. Retrogenia refers to a diminutive chin in the AP position, but with normal vertical height. In cases where retrognathia is the cause of a diminutive chin, establishment of a harmonious nose-chin relationship will require orthognathic surgery.

Fortunately in practice major skeletal deformities are relatively rare. Most patients can achieve improved facial harmony, which compliments and influences decision making in rhinoplasty, with either chin augmentation or sliding genioplasty. This chapter will be the focus of these techniques.

Finally some mention of the benefit of chin augmentation for the aging ptotic chin is appropriate. Soft tissue laxity and volume changes can facilitate ptosis of the chin pad, which is unattractive during aging. In the extreme form a ptotic chin is referred to as a witch’s chin. It has been noted to occur more commonly in edentulous patients who experience alveolar bone re-absorption, a decrease in vertical height and reduced chin pad fixation to the mandible. A chin implant is a valuable option to these patients as it can increase chin projection when appropriate and re-drape soft tissues with a resultant improvement in chin contour.

Before discussion of the technical aspects of skeletal changes of the chin, mention of soft tissues considerations is of importance. Five soft tissues considerations that pertain to the chin include: lip volume, submental contour, the effect of jowls, mentalis muscle tone, and chin pad ptosis. Specifically, many patients with retrogenia are noted to have increased mentalis muscle tone and associated chin dimpling. This occurs because the mentalis must contract to improve lip seal. Increased chin projection post-operatively provides better foundation for the lower lip, subsequently assisting with lip seal and relaxing the mentalis muscle.

OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Alloplastic Implant

There are various alloplastic implants used for chin augmentation, each with advantages and disadvantages. The harder implants are more permanent and offer increased definition, however their rigidity can necessitate a larger incision (unless the implant is composed of two parts). Implant materials such as mersilene mesh, pre-formed expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE, Gortex™), and silastic have the advantage of being malleable and offering a softer, more natural feel. Mersilene, porous polyethlene, and ePTFE allow fibrous in-growth, whereas silastic implants tend to develop a surrounding capsule. Studies have shown that firm implants result in variable amounts of bone resorption. Fixation of the implant with screws or suture can help reduce micro-motion of the implant, which is believed to be the reason for bone resorption.

The method of implant placement is also an important consideration. Implant material can be placed via an extra-oral or intra-oral approach. The intraoral approach avoids a visible scar, but a slightly higher incidence of implant infection (2%). Furthermore, intraoral placement can disrupt the attachment of the mentalis muscle to the mandible, which can cause the implant to shift postoperatively. Extra-oral placement of the implant has a slightly lower incidence of infection (1%). Placement of the implant inferior to the mentalis muscle can increase stability. Aynechi et al (2012 Oto-HNS) described a variation whereby intraoral placement of the implant is performed through a vertical incision between the two heads of the mentalis muscle permitting placement below the mentalis muscle.

Ancillary submental liposuction is another consideration to reduce fullness and allow soft tissue re-draping around the newly shaped bony framework. The 4mm submental incision for liposuction can easily be extended to 1 cm to place an implant.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE – Chin Implant

Placement of a chin implant can be performed through either an intraoral or submental route. The submental approach is preferred, and is the method described. The attached video shows all methods that are described (SEE VIDEO).

Extraoral Approach:

The patient is prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion and a 3 centimeter horizontal incision is designed just posterior to a submental crease.

Local anesthetic with approximately 10 mLs of 1:100,000 epinephrine is infiltrated into the planned incision, along the lower border of the mandible and on the anterior and lateral surfaces. Frequently submental liposuction is performed at the same setting to provide better definition. The submental and submandibular target areas are marked in the preoperative area with the patient sitting upright. The submental and submandibular triangles along with the chin area are infiltrated with a more dilute solution of lidocaine with 1:100,00 epinephrine. Typically 0.5% lidocaine with 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 epinephrine is used following dosage guidelines based on the patient’s weight. A mental nerve block may be added. If the chin augmentation, liposuction and rhinoplasty are the only procedures being performed, then either sedation or general anesthesia is acceptable. If general anesthesia is employed the endotracheal tube is secured with a braided suture around the neck of an incisor. The liposuction is performed first with a 4mm incision and a 3mm canula. If desired, an incision can be added at the base of the earlobe to permit multidirectional liposuction. Upon completion of liposuction the incision is extended along a horizontal line 2-3 cm posterior to the chin crease to minimize the risk of a depressed scar (Figure 5).

Skin is incised with a #15 blade and dissection with guarded tip monopolar electrocautery is performed down to the mentum of the mandible, which is further exposed. The soft tissues over the anterior 2 cm of the mentum are elevated just superficial to the periosteum. The midline is then identified in relation to the facial structures and marked. One centimeter lateral to the midline a 1 centimeter vertical incision is made in the periosteum. Lateral, sub-periosteal pockets are then developed with a freer to receive the ends of the chin implant. These precise pockets extend along the inferior mandible and lie below the mental foramen and extend to the body of the mandible. The elevator is levered laterally lifting the periosteum and creating a pocket for the tail of the implant. In virtually all cases the mental nerve is visualized, assuring the surgeon that it is intact and the tunnel is being prepared in the proper location. Do not elevate over the lower border of the mandible or the implant can migrate into this area creating an unnatural contour. An Aufricht retractor is placed into the pocket and is ideal for lifting the soft tissues and facilitating placement of the implant.

The chin implant is soaked in gentamycin solution and the pocket is irrigated with the same. The first phlange is placed into the pocket with the use of the Aufricht retractor and clamp. The silastic implant is then bent acutely on itself so that the second phlange can be inserted into the remaining pocket, again using the Aufricht to define the pocket and lift the soft tissues. Rarely, a suture is tied to the end of the implant to guide placement into the pocket.

The soft tissue is then redraped and the patients profile and AP views are examined for smoothness and symmetry. If satisfactory, the midline of the implant is secured to the midline periosteum of the mandible with a prolene suture to prevent migration. In a limited number of cases the implants are further stabilized with a self-drilling titanium 1.3 – 1.5 mm screw that is countersunk into the implant. This is helpful if the pocket was inadvertently made too large or if the new implant is serving as a replacement for one that was slightly larger, as now the pocket is too large.

Frequently the implants can be custom carved to adjust the shape to the unique aesthetic features of the patient. Most often this involves either shaving some projection on one side to accommodate facial asymmetries or trimming down the lateral projection for a woman with fine facial features, achieving anterior projection without excessive lateral augmentation. A 10 blade is preferred and the implant is grasped with a forceps to avoid glove contact. Two aesthetic concepts are of critical importance. It is important to never provide such excessive projection that the labial-mental sulcus becomes too deep. If the chin is markedly retrusive then there is usually an orthognathic abnormality present and aesthetically it is better to have less than ideal projection than an excessively deep sulcus. Additionally, it is wise to never place an implant that only adds projection to the mentum unless very little augmentation is sought. The extended anatomic implant is best as it allows the transition from implant to mandible to occur incrementally. The more concentrated implants that just cover the mentum often create an indentation laterally that resembles a jowl, which is not a desired result. As an aside, many patients with microgenia have increased mentalis muscle tone that tends to create dimpling of the chin pad, which following implant usually resolves. It is also worth noting that soft tissue elevation should be performed just superficial to the periosteum anteriorly. Laterally, dissection more superficially risks injury to the mentalis muscles with resultant dimpling postoperatively.

The wound is copiously irrigated with antibiotic solution and closed carefully in layers. Increased time is spent on a meticulously layered wound closure so as to minimize infection. Antibiotic ointment and a bandage are placed followed by a plastic barrier drape to minimize contamination during the rhinoplasty. At the completion of surgery we apply a spandex garment for 24 hours to apply gentle pressure to reduce edema. Antibiotic prophylaxis is routinely given peri-operatively and no additional antibiotic coverage is used unless indicated by other procedures.

Intraoral Approach:

Implant placement from an intraoral approach is rarely used. The extraoral approach provides increased stability and the incision is usually 2 cm and rarely requires revision. The risk of infection is minimally different (2% vs 1%) so it is not a primary determinant. The attachment of the mentalis to the mandible is a significant buttress preventing superior migration when the extraoral approach is used.

If the intraoral approach is selected the majority of the surgery follows the same guidelines as the extraoral approach. A few differences do exist. A 3 cm incision is made through the unattached oral mucosa preserving 6-10mm between the incision and the attached gingiva. The incision can be extended through the periosteum with a fine tipped insulated cautery. The origins of the mentalis muscles are defined and dissection carried between the two muscled to the inferior border of the mandible. Lateral soft tissue elevation is also performed subperiosteally. Retraction is performed cautiously to avoid extensive detachment of the mentalis muscles. A screw can be used to fixate the implant or the pocket created to allow a precise fit. Anchoring sutures are usually not used. The incision is closed with an absorbable running horizontal mattress suture. A second layer of a running locked absorbable suture is placed at the incision edge. The other details of the surgery are the same as described above.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: Mandibular Horizontal Sliding Genioplasty

The mandibular horizontal sliding genioplasty is best done under general anesthesia due to the need for osteotomies. The mandibular horizontal sliding osteotomy is recommended for patients with horizontal and / or vertical excess or deficiency, or asymmetries. The patient’s profile will determine the preferred technique aided by a lateral cephalometric radiograph. A tracing of the radiograph or dedicated software will determine the necessary correction. An orthopantomogram will yield additional information regarding the exact position of the tooth roots that must be avoided. A one third:two thirds rule of thumb is based on the root being twice as long as the length of the crown. A bit of caution should be taken if the osteotomies extend to the level of the canines, which are the longest teeth in the arch.

Both intraoral and extraoral approaches have been described. Our preference is intraoral originally described by Trauner and Obwegesser. General anesthesia with induced paralysis helps with the advancement to counter the remaining muscle fibers attached to the bony segment.

The face and mouth are prepped with betadine and chlorohexedine solution respectively. The mandibular buccal sulcus is infiltrated with 1:100,000 epinephrine. An incision is made in the labial mucosa in the depth of the vestibule. Care is taken to identify the mental nerves bilaterally before using cautery, which is then utilized to deepen the incision to bone. The periosteum is then sharply elevated to reveal the segment that is to be advanced (Figure Blood supply to the advanced segment is maintained by preserving the soft tissue attachments along the inferior border. Injury may still occur to the mental nerves from traction and stretching. Paresthesias are common and usually transient.

A reference mark is made on the bone and soft tissue as a reference for any later manipulation of the segment, and re-establishment of the midline. The osteotomy is performed with a sagittal or reciprocating saw. It is usually started in the midline, 10-15 mm above the inferior border, to include the most prominent aspect. The cuts are extended laterally based on the preoperative planning. This is facilitated by tapering below the mental foramen to preserve the mental and inferior alveolar nerves. These cuts can be tailored depending on any mandibular asymmetry that is noted with preoperative planning. A fine osteatome is utilized to complete cuts if necessary. The thickest segment which is usually the middle genial aspect is then fixated in the pre-planned position. 1.3 or 1.5 mm miniplates are common but lag-screw technique or little-used wire fixation can be utilized.

The wound is irrigated with copious saline or antibiotic solution. Hemostasis is obtained, and the incision is closed with a water-tight seal in two layers. Closed drains can be used but are not necessary. A supportive dressing with ice is applied the first 48 hours, then simply support for the next 5-7 days.

Augmentation via sliding osteotomy is limited by the thickness of the symphysis. Wedge osteotomies can shorten the chin and inter-positional bone graft can be added to lengthen the chin. The amount of soft tissue change optimally equates to the amount of change in bone.

Chin augmentation utilizing sliding osteotomy is a more versatile technique. It can be used to lengthen and shorten the chin. Careful preoperative planning is essential and includes additional radiographs to ensure a predictable outcome.

Postoperative care includes daily cleaning of the incision line with half-strength hydrogen peroxide and a petroleum based ointment. We continue antibiotic prophylactic coverage for 48 hours to cover oral flora in the clean, contaminated intraoral wound. We usually choose cephalexin or clindamaycin depending on allergy status. Post-operative assessment consists of clinical and radiographic analysis. Permanent sutures are removed at 5-7 days. A suspensory jaw dressing is used for the first 24 hours. Post-operative assessment consists of clinical and radiographic analysis.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications following chin augmentation are rare. Infection occurs less than 2% of the time with the route of implant placement being an important determinant (a higher infection rate corresponding to intraoral placement). With sliding osteotomies, unfavorable osteotomies and malposition can occur. The risk of hematoma is quite low as there is very little potential space created by the procedure. Sensory disturbances from nerve injury can occur, but are usually transient in nature. Disruption of the smile can occur, as dissection for extra-oral placement causes some temporary disturbance of the depressor anguli oris (DAO) muscle and mentalis muscle. With the extra-oral approach, there is always a concern for adverse scarring, but keloids and hypertrophic scars are rare in this region.

The need for revision surgery is always a possibility and is never as easy as simple removal and replacement. Depending on the material used, this may involve extensive subcutaneous dissection as seen with porous implants and/or excision of the capsule. If revision surgery is being performed to increase augmentation, then a limited amount of further dissection is necessary. In the case of decreased augmentation or malpositioned implants, the situation is more complex. There is often a combination of bone resorption beneath the implant and variable amounts of reactive bone formation at the periphery. Removing an implant may reveal an irregular bony contour necessitating contouring with powered instruments. Placement of a smaller implant is immobilized with screw fixation to avoid purchase cialis implant migration within the larger pocket.

Patients referred for implant removal require special consideration. Thorough investigation of the motivation for removal is required. The consultation should explore the patients initial aesthetic desires, the current chin contours, and the likely result after implant removal. If a firm implant was used previously then there is often underlying bone resorption and removal of the implant may create a less projected chin than the patient had preoperatively. In addition, the pocket that developed around the initial implant may not contract and a ptotic chin may develop. For these reasons we recommend that these patients consider replacing the implant with a smaller one as described above.

CONCLUSION

When considering rhinoplasty one must establish harmony between the middle third and lower third of the face. Chin-nose aesthetics is integral to the overall appearance of the nose. Careful analysis of the chin will direct the surgeon towards augmentation or reduction, and the appropriate surgical technique. Optimizing this relationship will improve the overall rhinoplasty result and create a satisfied, happy patient.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed J, Patil S, Jayaraj S. Assessment of the chin in patients undergoing rhinoplasty: what proportion may benefit from chin augmentation? Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2010 Feb;142(2):164-8.

- Powell N, Humphreys B. Considerations and components of the aesthetic face. In: Powell N, Humphreys B, editors. Proportions of the aesthetic face. New York: Theime-Stratten; 1984. 1-40.

- McCarthy JG, Ruff GI, Zide BM. A surgical system for the connection of the bony chin deformity. Clin Plast Surg 1991; 1:139-52.

- González-Ulloa M, Stevens E. The role of chin correction in profileplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1968 May;41(5):477-86.

- John L. Frodel. Evaluation and treatment of deformities of the chin. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 13 (2005). 73-84.

- Dolphin Imaging & Management Solutions Headquareters North America-US/Canada 9200 Eton Avenue Chatsworth, CA 91311-5807 USA

- Trauner R, Obwegesser, HL: The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. Part 1. Surgical procedures to correct mandibular prognathism and reshaping of the chin. Oral Surg 10:677-689, 1957