INTRODUCTION / BACKGROUND

The alar base plays an important role in the overall appearance and proportion of the nose. An overly wide or flared alar base will lead to a “bottom heavy” nose and disrupt the delicate balance of an otherwise properly executed rhinoplasty. Alar base refinement is often incompletely and inadequately described.1 The techniques to repair nasal base disharmonies have widely expanded over the last century.

Improvements first date back to 1892 when Dr. Robert Weir corrected the lateral alar flare of a post-operative rhinoplasty patient. The lateral flare had resulted from an iatrogenic nasal tip deprojection in the preceding months. The breadth of the nostril was reduced with an incision in the alar-facial groove. A semilunar piece of tissue was excised.2 This history emphasizes a central concept of rhinoplasty: the bony and cartilaginous complex of the nose and midface is the foundation on which the soft tissue rests. Another way of saying this is that, the ala is a tent which rests on bony and cartilaginous supports. As Kridel has explained, the decision to modify the alar base should only be made “after the establishment of the proper septal, columellar, dorsal, and tip contour and position” has been dictated.3

The Weir technique opened the door for alar base modification. In 1931, Joseph and Milstein modified the Weir incision to avoid the “classic” external scar by removing a small internal wedge on the vestribular side of the alar-sill junction.4 In the 1943, Gustav Aufricht experimented with over 20 geometric excisions of tissue from the alar rim to the nasal sill.5

It is reported that from a low of 15% to a high of 90% of rhinoplasty involves alar base manipulation.6 The discrepancy in the prevalence is due to variable patient population, rhinoplasty techniques, and operator preference. As these techniques become more popular, the prevalence of complications also increases. The operative skill set of alar base modification is neither technically difficult nor time consuming, yet many surgeons find that obtaining a predictable long term result from an alar base modification can be challenging. Aside from inexperience, a main difficulty relates to logistics. The alar base should be modified at the end of the operation to avoid altering the skin envelope before the structural nasal support has been created. At this point, the tissue is swollen and distorted from surgery. Many complications of alar base modification are complex to repair. It is often easier to perform the procedure than to repair the consequences.

To appreciate the nuances of alar base modification, the normal alar base anatomy, as well as the aesthetic ideals must be understood. Using this foundation, the surgeon has a wide armamentarium of techniques available to correct specific alar base abnormalities and associated complications. Only with a depth and breadth of knowledge will the adept surgeon be able to anticipate and treat alar and nasal base disharmonies.

ANATOMY

The ala abuts the nasal tip anteriorly and the nasal sidewall superiorly. The crescenteric alar groove frames the ala and deepens as it extends posteriorly. This posterior portion of the alar groove is often called the alar-facial sulcus and separates the ala from the cheek and apical triangle of the lip. (Figure 1)

|

| (Figure 1) |

The nose is divided into the alar base and vestibule at its most caudal aspect. The size, shape and resiliency of the nostrils and alar base vary depending on the ethnic and individual distribution of the fibrofatty areolar tissue confined to that area. Inside the nares, the nasal vestibule is bounded medially by the membranous nasal septum and laterally by the alar sidewalls. The columella is the soft tissue overlying the paired medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages that separates the nostrils. The columella usually makes a smooth transition over the footplates of the medial crura and then curves laterally to join the nasal sill. Tardy defines the nasal sill as the intranostril region between the medial crural footplate/columella complex and the alar facial groove.7 This area may be normally notched or smooth, depending on its transition with the alar-facial groove.

The ala itself is a vital cosmetic and functional landmark. The distal free margin of the alar lobule and the transition from the shadows of the alar groove to the reflection of the convex surface of the ala are important visual landmarks. The ala also frames the lateral aspect of the external nasal valve, a critical path for airflow during inspiration. Altering the position of the ala during reconstructive surgery can compromise function of the external nasal valve; this is not the case for nasal base surgery. Relative to the nasal tip and sidewall, the alar tissue is more compliant and does not contain cartilage because the position of the lower lateral cartilage does not cross the alar groove.8 The alar lobule consists of skeletal muscle and fibrofatty areolar tissue that is enveloped by dermis and epithelium on both the internal and external aspects.9 The lack of an intrinsic cartilaginous skeleton and the complete absence of support at its distal free margin make this delicate structure particularly susceptible to distortion. Because the caudal margin of the lower lateral cartilage is about a centimeter superior to the nostril rim, it is unaffected by alar reduction procedures.10

While the alar lobule itself does not contain cartilage, the ala gains dynamic and static support from the close relationship of its muscles with the osseous-cartilaginous framework of the nose.8 The lower lateral cartilages gain stability from loose connective tissue that links the domes of the lower lateral cartilages and from direct connection of the medial crura with the caudal septum.11 A fascial system, called the “pyriform ligament,” stabilizes the entire cartilaginous framework by connecting the lower lateral cartilages with the pyriform rim.12

The actions of skeletal muscles on the position of the nasal base and alae remain poorly understood.8,12,13 The dilatator naris muscle comprises the main muscular component of the alar lobule. The dilatator naris muscle originates from the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage and inserts directly onto the alar skin.8 Contraction of this muscle helps to open the nostril. The alar portion of the nasalis muscle originates from the fossa incisiva of the maxilla and inserts on the alar skin and accessory cartilages near the pyriform aperture. Contraction of this muscle may dilate the nasal valve area by drawing the accessory cartilages, and by extension, the lateral crura, laterally.8 Additional dynamic support to the ala may come from the levator labii superioris alaque nasi, that pulls the ala superiomedially13 and from the levator labii superioris muscle that partially inserts on the vestibular skin of the nasal vestibule and widens the nostril by pulling it superolaterally.12

In addition to the structural and supporting tissue of the ala, the sensory and motor innervation, vascular supply, and lining play intricate roles in nasal alar anatomy. The dilator naris anterior, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi and alar nasalis muscles are innervated by the buccal branch of the facial nerve (CN VII). The sensory innervation to the caudal and lateral portions of the nose are supplied by the external branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (branch of V1) and branches of the infraorbital nerve (V2).14

The vascular supply to the nasal base is derived from multiple branches of both the external and internal carotid artery systems. The facial artery gives off the superior labial and angular arteries, its two terminal branches, which contribute blood supply to the ala and nasal base. Specifically, the base of the columella and the sill are supplied by branches of superior labial artery. This artery also gives off the columellar artery, which runs superficial to the medial crura to supply the tip.14 Branches of the infraorbital artery, lateral nasal artery and the external nasal branch of the anterior ethmoid artery also supply blood to the area.14

The external nasal valve is the area bounded by the caudal edge of the upper lateral cartilage superolaterally, the nasal ala and attachment of the lateral crus laterally, the caudal septum and columella medially and the nasal sill inferiorly.15 Clinically, alar support is important to a functional airway. A weakening or narrowing of the alar base may cause nasal obstruction from an external nasal valve that closes upon inspiration.16

AESTHETICS & PRE-OPERATIVE ANALYSIS

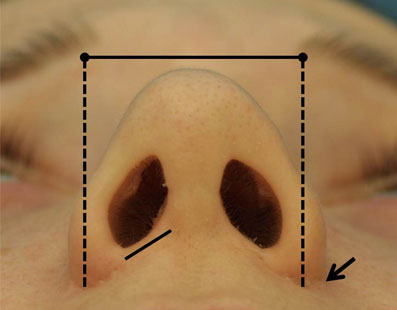

The aesthetically ideal Caucasian tip takes on the shape of an equilateral triangle when assessed from the base view. The infratip lobule generally comprises about one-third of the height of the triangle and the columella and nostrils compose the remaining two-thirds.17 The width of the lobule or superior one-third of the base view is about 75 percent of the entire nasal base width. (Figure 2) The ideal nostrils are elliptical or pear shaped, symmetric, slightly wider than the columella and inclined medially at about 30 to 45 degrees to the vertical axis of the columella.18,19 The columellar width should equal one fifth of the entire nasal base distance. The thickness of the alar sidewall and the overall character of the patient’s skin can also be evaluated from the nasal base view. The alar sidewall is about one-fifth of the width of the nasal base since an excessively thick sidewall can detract from the overall harmony of the nose.

|

| (Figure 2) |

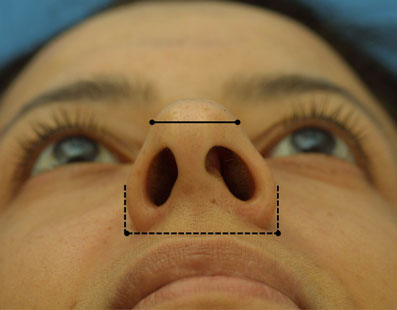

The frontal view is also useful for analyzing the nasal base width. This width should approximate the intercanthal distance. (Figure 3) When dividing the face into vertical fifths, according to the aesthetic ideal, the nasal base width should be one-fifth of the face and also be equal to the width of one eye. However, some surgeons, like Guyuron, prefer that the width of the alar base should extend about 1mm wider than the intercanthal distance on each side.20 Powell and Humphreys define the nasal base width as the distance between the alar-facial grooves. This distance should be approximately 70 percent of the nasal length, as defined by the distance from the nasal tip to the nasion.21 The appearance of the nostril rims and the columella are ideally arranged like a “seagull in flight.”22 This lends to a natural appearance of the alar-columellar complex.

|

| (Figure 3) |

Alar flare has been defined as the amount of lateral excursion of the alar wall that extends beyond the alar-facial groove.23 Some have even explained that it is significant if the alar rim extends greater than 2mm beyond the attachment of the alar base to the face.22 This is also the site of the maximal alar convexity that exists above the alar facial groove.

When analyzing the nose from a lateral or profile view, there should ideally be about 2-4mm of columellar show. The nostril can be bisected on the lateral view at its widest portion and there should be 2mm both above and below that bisecting line.10 While many surgeons talk about the alar base ending at the subnasale, Guyuron professes that the ideal alar base should actually end about 2mm caudal to this junction of the columella and the upper lip.20 Crumley described the normal vertical insertion of the ala to be anywhere from 2-3mm above the columellar-labial junction.19

Nasal base width greater than the intercanthal distance may be a general guide that alar base reductions are indicated. However, Tebbetts explains that the most important indication for alar base reduction is a nasal base that is disproportionately wide as compared to the overall nasal width.24 The goal of rhinoplasty is overall nasal balance and harmony with surrounding facial structures. In patients with wide, platyrhine noses, conforming to the Caucasian ideal is a mistake. Most ethnic patients from African American, Mestizo and Asian backgrounds who want smaller nasal bases also want to retention retain their cultural heritage. These patients do not want a Caucasian appearing nose, but instead a nasal base that maintains harmony with the rest of their nose without effacing their ethnicity. The “rules” are also different for patients with platyrhine noses. According to a study by Porter and Olson, the ratio of the interalar distance : intercanthal distance in African American men and women is 1.3:1 and 1.25:1, respectively.25 Also, Sim et al. reviewed 100 Southern Chinese female faces and explained that the nasal base width was greater than the intercanthal distance, alae were more flared and nostrils were more horizontally oriented when compared to North American women.26 Finally, Bernstein expounded on the wide ethinic and individual variability that exists among patients in regards to their alar bases.27

Careful pre-operative planning and anticipation of the nasal changes that take place is essential when considering alar base reduction. Poor anticipation of the changes that occur to the nasal base from intra-operative maneuvers relating to dorsal height, tip projection and rotation is one reason that alar base reduction is sometimes overlooked.24 Most surgeons pre-operatively discuss the possibility of narrowing the alar base with their patients since the final determination is an intra-operative one.

OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS & PROCEDURE

Most rhinoplasty is completed in a progressive, step-wise fashion. After the bony-cartilaginous framework of the nose has been corrected, the soft tissues are considered. Any change in the nasal tip has the potential to alter the ala and nostrils. Tip projection and/or rotation upwards can narrow the ala as well as narrow and elongate the nostrils. Several authors have noted that deprojection of the nasal tip may lead to subsequent widening of the nostrils; 15 to 20% of deprojection rhinoplasties may require narrowing with wedge-shaped resections out of the lateral ala.3,28,29 For this reason, it is important to assess the nasal base pre-operatively and intra-operatively after the nasal dorsum and tip have been repaired.23

Nasal base modifications can improve nostril shape and orientation, reduce alar flaring, improve nasal base width, correct nasal hooding, improve symmetry and create overall facial harmony. The alar base has an internal circumference involving vestibular mucosa of the nostrils and an external circumference of alar skin. Reduction of the internal circumference will diminish nostril size. Nostril sill excisions are termed internal alar base reductions because they do not address alar flare.23 On the other hand, wedge excisions from the base of the alar lobule to just above the alar facial groove will improve excessive alar flare, but will not narrow the nostril. This type of alar base modification is termed an external alar base reduction. The surgeon can therefore incorporate one or both techniques to tailor the amount of nostril or alar base reduction to the individual needs of each patient.

An extremely wide nasal base may require alternative or adjunctive treatments. Base narrowing sutures, or “cinching sutures”, are placed across the length of the patient’s nasal base. When these sutures are tightened, the distance between the bases decreases. At times a procedure to move the entire ala medially may be necessary for increased narrowing. A V-Y advancement of the skin just lateral to the alar-facial groove can also be performed, but must be tempered against the risk of placing a scar in a highly visible location.30 With meticulous care in closure, Kridel and Castellano report that the scars from the V-Y advancements can become imperceptible even though they are not hidden in the alar-facial sulcus.3

In order to achieve symmetry with alar base reductions, not only the amount of tissue to be removed but the type of excision must be considered. The most important factor in determining the success of the alar base modification is the determination of the particular segment of the alar base to be reduced, followed by the type and placement of the excision.22 Incisions involving the lateral ala should be made one half to one millimeter above the alar-facial sulcus so that the natural and distinct groove camouflages this incision. Nostril and nasal sill incisions are to be placed within the normal crease lines of the sill, such that there is no notching and the natural alar curve is maintained.22,31

Given the diversity of nasal base imperfections that can be addressed, each treatment option will be described. This will be followed by the presentation of a treatment algorithm that integrates these individual operative techniques.

TREATMENT OPTIONS:

| Problem | Treatment Option |

| Excessive Nostril Sill | Nasal sill reduction via internal alar base reduction |

| Excessive Alar Flare | Alar flare reduction via external alar base reduction |

| Excessive Nostril Sill and Alar Flare | Sliding alar flap (Both excisions of the nostril sill and alar lobule with medialization of the ala) |

| Excessive Alar Rim Width | Alar sidewall excision |

| Excessive Alar Hooding | Alar hooding reduction |

| Persistent Alar Base Width – Adjunctive Procedures | V-Y advancement & suture cinching techniques |

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Key instrumentation and materials:

• 5-0 Nylon or Prolene suture with possible 5-0 PDS deep suture

• Sharp measuring calipers

• Ruler

• 11 blade

• Surgical marking pen

• Fine needle driver

• Brown-Adson forceps

• Frazier tip suction catheter, size 8

Correction of Wide Nostril Sills:

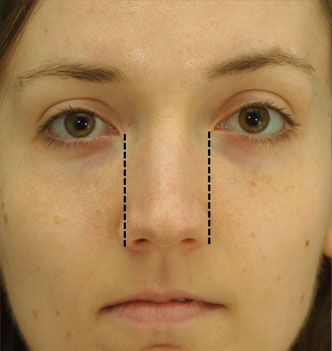

At the completion of the rhinoplasty, markings are made at the nasolabial junction in the columella midline, at the lateral-most points of each alar-facial groove, and at the sill crease. (Figure 4) The nasal base is locally injected with Xylocaine 1% with 1:100,000 Epinephrine, buffered 9:1 with 8.4%

|

| (Figure 4) |

Sodium Bicarbonate, directly into the nasal sill and alar-facial groove using a 27 gauge needle. After a ten to fifteen minute delay to allow for vasoconstriction, the alae are re-examined for asymmetry.

The correction of an excessive nasal sill requires the removal of wedge of tissue in what has been termed an internal alar base reduction.1,23,32 An internal alar base reduction involves a “V” shaped wedge excision of nostril sill. The nostril sill dictates where the excision can be made. In most patients, there is a notch or crease where the sill meets the nostril. Medial and then lateral sill incisions are made with a No. 11 blade, cutting away from the stab. It is recommended that Brown-Adson forceps are used to stabilize the wedge of tissue which is to be excised. After the sill tissue is excised, there is no medial repositioning of the alar-facial junction because, as stated earlier, this only affects the nasal sill rather than the flare of the ala.

The proper technique for closure should produce tissue stability with minimal scarring. First, the sill is approximated with a medial 5-0 Nylon tacking suture. If a wedge excision is to be performed in addition, this will be performed next. If the excision is ready for closure, meticulous hemostasis must be achieved. The use of cautery is uncommon and should be avoided unless absolutely necessary, as it can lead to impaired wound healing and objectionable scarring. If cautery is required, a bipolar cautery or narrow tip (Colorado tip) monopolar cautery should be used for improved precision. In the majority of cases, hemostasis can be achieved through suturing, especially if the deep muscle has not been violated.

The final closure should be free of tension, avoid step-offs, produce skin eversion, and return an even dermal texture. Buried 5-0 Monocryl sutures may be placed when tension is excessive. Closure of the skin with interrupted 5-0 Nylon or Prolene sutures allow for skin approximation with minimal tissue reactivity.

Correction of Excessive Alar Flare:

The correction of excessive alar flare requires the removal of wedge of lateral alar tissue via an external alar base reduction.1,23,32 This procedure is typically employed when the alar rim extends laterally more than 2mm beyond the alar base attachment to the face.22 An external alar base reduction involves a crescenteric wedge excision of the alar skin and will affect only the alar flare and not the nostrils or nasal sill. The alar flare is often addressed after any nostril narrowing as a sill excision may alter the relative amount of alar flaring.

The ala with greater flare is addressed first.1 A ruler measures the distance from the crease point of the sill to the midline (usually 10-12mm). A #11 blade is used to cut along the alar crease to a point approximately half-way up the ala. To estimate the required amount of alar flare reduction, the incised alar lobule is grasped at its caudal cut edge with a Brown-Adson forceps and pulled inferiorly.1,6 A No. 11 blade is used to excise this crescenteric wedge of tissue. Any incision that detaches the ala from the face should be made just anterior to the alar-facial groove to avoid abnormal scarring. The incision should not extend beyond the superior alar crease in order to prevent contraction and scarring in the superior alar crease. Warner and colleagues warn that excisions carried out too far laterally along the natural curve of the ala may result in an unnatural curve, a notch, or an unnatural insertion of the alar base.23

A tacking suture is placed at the midline of the reconstituted ala. If more alar narrowing is desired, the medial tacking suture is removed and additional alar tissue is resected. The wound is closed meticulously with interrupted 5-0 Nylon suture.

Combined Correction of Both Wide Nostril Sills and Excessive Alar Flare:

Rarely will an isolated problem with the alar base stand alone. The adept surgeon should integrate these various techniques when attempting alar base modification. In order to achieve maximal alar flare reduction with medial repositioning, a sliding alar flap can be utilized. From a reconstructive standpoint, this is an advancement-rotation flap. A considerable amount of internal nostril sill and external ala are reduced via an incision near the alar-facial junction and extending all the way through the lateral ala. After the nostril sill excision is performed, as described above, a cut is made with a #11 blade from the caudal aspect of that sill excision along a line parallel to the nostril sill, about 1-1.5mm above the alar-facial junction, and extending to the most lateral alar-facial marking. This incision releases the ala and allows it to slide as an advancement-rotation flap medially. This medial movement significantly narrows the alar base because the alar flap now fills the space once occupied by the excess nostril sill, before it was excised. Reduction of the volume, curvature, and flare of both the internal and external alar diameters will re¬sult from this procedure. The extent of reduction to both the internal and external alar diameters, however, is dependent on the angulation and geometry of the alar incisions.7 Varying the length and shape of the nostril sill excision, whether it is a square, trapezoid, rectangle or pentagon, will ultimately have an effect on the amount of alar base and flare reduction achieved.

Once the sill is slid into position, it is approximated with a medial 5-0 Nylon tacking suture. With that in place, a wedge excision of the alar lobule is performed next to reduce the alar flare, if necessary. In patients with large amounts of sill excised, a deep, buried 5-0 Monocryl suture can be placed to alleviate any wound tension on the incision. Finally, interrupted 5-0 Nylon sutures are used to close the incision. (Figure 5 A&B)

|  |

| (Figure 5 A) | (Figure 5 B) |

| (Figure 5 A&B) |

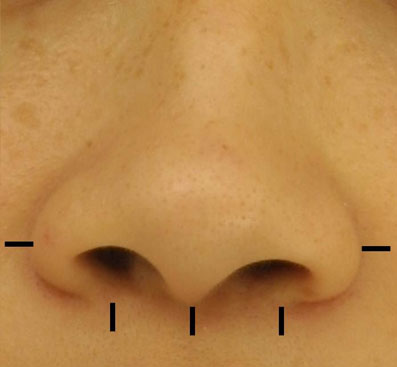

Correction of Thickened Alar Sidewall:

The rim of the ala can be abnormally thickened. The prevalence of alar sidewall thickening is different among ethnicities and is most common in the African platyrhine nose.33 A thickened alar rim cannot be completely corrected by traditional alar, sill or columellar base resection. The treatment of alar sidewall thickening involves a fusiform wedge excision, or a diamond shaped excision, to narrow a thickened alar sidewall.34

Correction of Alar Hooding:

Alar hooding, previously referred to as a hanging ala, occurs when the ala descends more than 2mm inferior to the columella. Alar hooding should be evaluated on direct lateral view. The etiology is developmental or iatrogenic. The downward displacement of the alar rim can be due to excessively thick skin, tissue softening, or caudal alar insertion. Thus, the ala “hoods” the columella and there is a loss of appropriate columellar show. This is often of insufficient cosmetic impact, and the surgeon should weigh placing a visible scar on the alar rim against the relative improvement that would be achieved through surgical correction.

If treatment is considered imperative, options include trimming the caudal rim of the lateral crus along with the lining vestibular skin, allowing for upward movement of the alar margin.22 This may lead to an external scar. A modern treatment approach removes an ellipse from the inner portion of the ala such that the natural curve of the ala is not disrupted. This is advantageous if alar hooding is combined with a thickened alar rim. The wound is closed primarily with a 6-0 running Nylon suture that is removed on post-operative day 4. Warner and colleagues23 have not had complications with scarring from this approach despite that on frontal view, the incisions are along a visible border.

Adjunctive Procedures for Correction of Persistent Alar Base Width:

Once the surgeon has tried to achieve alar base narrowing though one of the procedures listed above and there continues to be a persistently wide alar base, alternate procedures may be considered, depending on the etiology of the problem.

If the lateral insertion of the ala is responsible for a persistently wide nasal base, a V to Y advancement of the facial skin, just lateral to the alar-facial junction, can be employed to narrow the alar base. Kridel describes that first the nostril sill must be reapproximated with a single 6-0 Prolene stitch. Next, the lateral aspect of the wedge-shaped alar excision is drawn into the nasolabial fold with a single-pronged skin hook. A simple 6-0 Prolene or Nylon suture is used to approximate the “V” to create the stem of the “Y” in the nasolabial crease. The more sutures placed along the stem of the “Y”, the more the ala will be medialized.3 The result of a V-Y advancement is medialization of the ala, with a possible complication of scarring. In Kridel’s study, 25% of patients required post-operative dermabrasion after six weeks.3

Alar release with medialization also reduces a broad nasal base that has been inadequately narrowed by traditional techniques. There is a limit to the amount of soft tissue that can be resected before there is a distortion of alar anatomy and stenosis of the nostrils. In cadaver studies by Gruber et al. in 2009, both the caudal and cephalic ala were released via detachment of the anterior maxillary periosteum and pyriform ligament along the vertical pyriform rim, posterior nasal vault periosteum, and the pyriform ligament along the horizontal rim. The ala-pyriform distance was reduced 4.6mm on average. The advantage to this procedure is a tension-free medialization.35,36_ENREF_29 This technique does not create a visible incision and may result in increased nasal tip projection. The main drawbacks with this technique are difficulty in achieving long lasting results and prediction of the final alar base position.

In addition, suture cinching techniques can be employed to restore a narrow alar base width. Bertossi et al. describe a technique using a 3-0 Vicryl cross-suture. This suture travels from the alar base, across the transverse nasalis muscles to the contralateral side. It is fixed to the sectioned contralateral muscle. It is inserted on the adherent side of the gingiva, just above the canine teeth.37 Though not familiar to most facial plastic surgeons, this technique explains that through deep cross suturing, the nasal base can be corrected without external incisions. A less complex yet similar approach is a basal bunching suture placed intranasally which narrows the alar base and blunts the nasolabial angle. The complication with any of these suture cinching procedures is bunching of the nostril floor as well as excessive alar rounding.

POST-OPERATIVE CARE

Alar base incisions will tend to crust if not cared for appropriately. The patient applies antibiotic ointment to the wound immediately after the procedure three times a day. Patients are given hydrogen peroxide solution and instructed to gently clean any crusts forming around the sutures; the sutures themselves are not touched so that micro-motion along the suture line does not occur. Patients are seen on post-operative day number 1 and incisions are inspected, all crusts are gently debrided and antibiotic ointment is applied.

Typically, sutures are removed from the wedge excision on post-operative day 5 to 8. Steristrips can be used to reinforce the wound to assist healing if sutures are removed early. During suture removal, any epidermal debris in the suture holes is gently teased away with a fine forceps to avoid suture marks.

COMPLICATIONS AND THEIR MANAGEMENT

Overall, most patients are satisfied with alar base modification. For the minority, there are a variety of reported complications. The complications fall into broad categories: scarring, notching, and overall deformity. Inability to predict outcome from alar base refinement is among the most concerning challenges.

Nasal scarring may be noticed due to imprecise placement of incisions or poor wound healing. External incisions should be placed 0.5 to 1mm above the alar-facial crease to allow exact edge-to-edge suturing and to avoid suturing across a concavity. Maintaining the natural alar-facial crease preserves a prominent visual line which camouflages the nearby incision. Scarring does not appear related to ethnicity or sex.3 Keloid formation in the nasal base has never been reported. In cases of persistent post-operative scarring, dermabrasion can be employed after a delay of 4 to 6 weeks.3

Notching of the alar rim or nostril sill is the most reported complication. (Figure 6) The most common reason for notching is performing a wedge excision of the nostril that is poorly placed and closed under tension with no alar release. Foda reported a 30% incidence of notching in his first twenty cases of a combined technique utilizing both a nostril floor excision and external alar reduction. This notching was reduced to 5% by use of a stabilizing 5-0 Vicryl subcutaneous deep suture.38 The treatment of alar sill notching is challenging and complex requiring re-operation with possible cartilage or synthetic grafting materials. These corrective procedures have yet to be properly defined.

|

| (Figure 6) |

A step-off deformity can complicate alar base refinement. If there is misalignment of the two cut alar tissue edges, a ledge can form. Ideally, through proper marking, caliper use, and precise suturing, this complication can be avoided. Treatment of a step-off deformity involves re-incision and proper meticulous wound closure.

Wound dehiscence after alar base modification is rare, especially if a deep suture is placed and post-operative wound infection is avoided. The use of post-operative antibiotic ointment is customarily employed. Though wound dehiscence, step-offs and notching may be reduced with deep sutures, there is a tendency for deep sutures to extrude. Foda reported a 5% partial suture extrusion rate.38 This may have had more to do with suture choice (Vicryl) than any technical errors. Dissolvable monofilaments (Monocryl, PDS) may be better tolerated.

Symmetry is a goal in alar base modification. Asymmetry is reduced with careful pre-operative measurement and caliper use. Achieving perfectly symmetric nostrils with preexisting nostril asymmetries is nearly impossible. Cinelli describes a technique to minimize post-operative asymmetry called the “Calibrated Weir Operation”.39 It involves drawing a midcolumellar line from the nasolabial angle to the midpoint of the upper vermillion border, then bisecting this line and the columella with another perpendicular line. From the intersection of the two lines, one may measure the distance to the medial and lateral borders of a nasal base excision. Similarly, the senior author has found that precise identification of the midcolumella and lateral starting point of the nasal sill with calibrated precise removal of tissue has resulted in excellent symmetrical post-operative results.1

In certain cases of alar base refinement, asymmetry is especially complex. Cleft lip and palate cases and traumatic injury can lead to alar base asymmetries that are difficult to manage because the surrounding tissue is not uniform. Mazzola explains that unilateral alar base reduction can be achieved using a z-plasty technique in patients with cleft lips.40 On the other hand, trauma is usually associated with unpredictable swelling in the acute period and delayed repair must be considered.

Nostril stenosis is a surgical error of commission and can be avoided by conservative and appropriate narrowing. Adamson contended that the most restrictive anatomical region of the airway is the internal valve and in most cases with wide alar bases it would likely require a significant alar base reduction or concomitant external valvular pathology for the reduction to have any impact on the nasal airway.41 Surgical correction of overly narrowed nostrils is difficult and can involve a composite graft, local flap, and/or stent placement.42 In addition, alar bases which are excessively narrowed may require techniques which are not yet established to widen and provide an adequate airway and natural contour to the nostril.

A “tear drop” or “Q” deformity may result from overly aggressive excisions of the lateral alar wall. This deformity is noticed at the base of the nostril where the nostril rim forms the circular part of the “Q” and the tail is the scar. The phrase, “preserve the curve” was coined to highlight the importance of preserving the alar-facial groove. Toriumi has noted that meticulous closure has minimized this deformity and hidden resultant scars satisfactorily.43

A “tent pole” appearance can result from a combination of reduction of alar flare by excessive nasal ala narrowing along with increased tip projection. This deformity is challenging to fix because it requires deprojection of the nasal tip, the addition of bulk to the nasal base, or widening the alar rims. Aside from deprojection of the tip, repair remains uncharted.

Finally, a bowling pin deformity can result in a subset of patients. If the patient has a vertically oriented alar axis and undergoes alar resection, the alar axis will then point inferiorly and medially. The nasal tip will remain bulbous. The patient is likely to develop a disproportionately narrow or “pinched” nasal base, known as a bowling pin deformity. Techniques which narrow the overall nasal base, such as an alar release, avoid that problem.35

CONCLUSION

Upon the completion of rhinoplasty, attention should be turned to the nasal base. Alar base refinement has the potential to significantly improve facial harmony. There are many techniques available to improve the alar base. An appreciation of the causes, treatments, and pitfalls of alar base modification will aid the surgeon in creating symmetry and beauty.

The biggest challenge of alar base modification is predicting the final result. One of the most difficult complications to overcome is over-resection. Under-resection can always be revised, but over-resection may cause irreversible tissue loss and deformity. Regardless of the type of modification, a conservative approach to alar base refinement is essential. It is easy to trim and challenging to add to the alar base.

In a 2005 study describing the long-term effects of alar base reduction, Bennett and Constantinides suggest that vertical flare and nostril height are the only significant long-term differences seen in patients who required alar reduction. No significant changes were seen in alar base width, flare width, or base height.1 Reasons for this unpredictability include that (1) the increased flare was caused by the preceding rhinoplasty involving tip deprojection and without reduction, post-operative flare would be excessive, (2) the alar base surgery was overly conservative, and (3) the flare was initially reduced but stretched back to a more flared position during wound healing.1

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

Alar bases which are excessively narrowed may require techniques which are not yet established to widen and provide an adequate airway and natural contour to the nostril. Additional research and techniques will assuredly be defined in the coming years to help address these complex disharmonies.

ALAR BASE MODIFICATION – CASE STUDY

History

We present the case of a 19 year old man who presented to the senior author’s (MSC) office in consultation for a cosmetic rhinoplasty. The patient had specific complaints of droopy nasal tip, especially when smiling, an offset and wide nasal dorsum and an increased width of the nasal base. The patient additionally explained that he would like a “less ethnic” nose and wanted a significantly nasal tip that was significantly rotated.

On evaluation, the patient had no previous medical or surgical history, other than some fractioned CO2 laser resurfacing treatments in the past. The patient was taking no medications or supplements and had no allergies to medication. There was no history of any tobacco, alcohol or illegal substance use.

Analysis

Evaluating the pre-operative photographs (Figure 7 A-K), the patient has thick Mestizo/Latin skin. The frontal view reveals that the upper, middle and lower thirds are all deviated to the left as a unit. The middle and upper thirds of the nose are wide ventrally. The left nasal bone is convex and flared laterally. On frontal view, the nasal base width is greater than the intercanthal distance, with more alar flare on the left side than the right. The alar flare extends beyond the alar-facial groove 3mm on the left side and 1mm on the right. Also, the nasal tip is amorphous and bulbous. On the top-down view, the deviation of the entire nasal pyramid and cartilaginous skeleton to the left side is well seen.

|  |

| ( Figure 7 A ) | ( Figure 7 B ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 7 C ) | ( Figure 7 D ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 7 E ) | ( Figure 7 F ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 7 G ) | ( Figure 7 H ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 7 I ) | ( Figure 7 J ) |

| |

| ( Figure 7 K ) | |

| (Figure 7 A-K) |

On the lateral view, a dorsal hump is present with a small amount of tip ptosis and slight underprojection. The addition of the smiling lateral views help to further bring out the ptosis in the nasal tip. The oblique views help to further define that the highest portion of the dorsal hump is occurring at the osseocartilagenous junction.

Analysis of the base view shows an increased alar base width that is greater than the intercanthal distance and that is asymmetric. The alar base is more laterally oriented on the left side than on the right. The patient has a deviated caudal septum that is off of the maxillary crest to the left. The patient’s nostrils are horizontally oriented and are slightly asymmetric from intrusion of the caudal septum into the left nasal cavity.

Surgical Technique

The patient was brought to the operating room and given IV sedation for the procedure. 1 gram of Ancef and 8 mg of Dexamethasone were administered pre-operatively. Next, 4 ml of 4% cocaine was placed on pledgets into the nostrils. 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine was buffered 10:1 with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate and injected in and about the nose with a 27 gauge needle. The full face was prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. An inverted gull wing incision was made in the columella and connected with bilateral marginal incisions for an external rhinoplasty approach. The skin and nasal soft tissues were elevated off the underlying cartilage and bony scaffold. The interdomal ligaments were divided and the caudal nasal septum was identified. Bilateral septal mucoperichondrial flaps were elevated.

The nasal septum was deviated to the left inferiorly as the septum had a large cartilaginous spur off of the maxillary crest. The bony-cartilagenous junction was disarticulated posteriorly and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid and vomer were resected, along with the cartilaginous spur. Inferior and posterior septal cartilage was harvested for later use in the case. At this point, the remaining “L-strut” was still deviated to the left side. It was then repositioned from the left side of the crest to the right side and maintained there with a through-and-through 4-0 PDS suture. The septal flaps were then reapproximated and closed with through-and-through 3-0 Chromic mattress sutures.

A dorsal hump reduction was then performed with a 10mm Rubin osteotome for 3mm of reduction. Further cartilaginous reduction of 2mm was also perfomed near the bony-cartilagenous junction with a #15 blade. Bilateral low lateral intranasal perforating osteotomies and a left intermediate osteotomy were performed. The nose was still crooked at this point and therefore, a percutaneous 2mm cross-root osteotomy on the left was performed with excellent overall nasal straightening. The nasal bones were narrowed and symmetric at the end of the osteotomies. The upper lateral cartilages were left attached to their dorsal attachments during the procedure and no reattachment was required.

Attention was then turned to the nasal tip. The tip cartilages were cut at their cephalic edges for 4mm of reduction. The medial crural feet were dissected free from their posterior septal angle attachments and mobilized medially. A 4-0 PDS suture then imbricated the medial crural feet to the posterior septal angle. A large septal extension graft was fashioned from the previously harvested septal cartilage and placed between the medial crura and then overlying the cartilaginous septum to the right. This was secured with through-and-through 4-0 Monocryl sutures to the medial crura. In order to provide projection and rotation to the poorly projected domes, the vestibular skin was undermined off the undersurface of the lateral crura and a lateral crural steal was performed bilaterally with a 5-0 Prolene suture. Although there was good improvement in domal height, additional projection was required. Therefore, a tip graft was fashioned from septal cartilage and placed with the concave side caudally positioned, in order to create projection without excessive rotation. This was secured in place with a 5-0 Prolene suture. Also, one of the wide, soft cartilage excisions from the cephalic trims was cut in half and each half was used on either side to soften the transition from the tip graft to the surrounding tissue. These transition grafts were secured to the tip graft and the lateral crura with 5-0 PDS suture.

At the conclusion of the case, the tip was rotated and projected appropriately with excellent columellar strength and straightening. The columellar incision was closed with a buried 5-0 PDS suture to take off tension and interrupted 6-0 Nylon sutures were used on the skin. The marginal incisions were closed with interrupted 5-0 fast-absorbing gut sutures.

Finally, attention was then turned to the alar bases. The left alar base was asymmetrically wide compared to the right. Beginning on the left, the side of greatest alar flare, a determination of the amount of alar flare and nostril sill that needed to be reduced was marked out. These distances were not only drawn, but also sharply marked with stabs from the calipers. Medial and then lateral incisions are made within the nasal sill on the left, starting inferiorly and cutting upward at a right angle with a #11 blade. The caudal portion of both incisions is then connected with the #11 blade along a line parallel to the nasal sill that runs just above the alar facial groove. This incision travels to the most lateral aspect of the alar-facial groove. A 7mm excision along the nasal sill on the left side is performed; the sill is re-approximated medially with a 5-0 nylon tacking suture. At this point, the amount of excess alar flare is estimated by grasping the cut edge of the ala with a Brown-Adson forceps and pulling it inferiorly. Subsequently, a 3mm reduction of the cut edge of the ala is removed as a wedge excision with a #11 blade. Another 5-0 Nylon tacking suture is placed at the midline of the newly reconstituted ala. After inspecting the result, all suture lines are closed with interrupted 5-0 nylon sutures. If there is undo tension on the wounds, a buried absorbable monofilament suture (e.g. 5-0 Monocryl) may be added.

Next, the alar base modification on the right side is performed using the same technique. Due to the pre-existing asymmetry, only a 5mm sill excision was necessary on the right side. Since there was no significant alar flare on the right side, a wedge excision of the cut edge of the ala was not needed.

The nose was then taped and casted in the usual fashion. Telfa packs with Bacitracin ointment were place into the nostrils bilaterally. The patient was recovered and the packs were removed prior to discharge.

Post-operative Follow-up

Two year follow-up was obtained on this patient after his septorhinoplasty with alar base modifications. The 2 year post-operative photographs (Figure 8 A-K) reveal that the patient has appropriate nasal tip projection and a slightly over-rotated appearance. Even though this amount of rotation may not be considered aesthetically ideal, the patient was very clear that he was interested in an over-rotated look and is extremely happy with the final result. Additionally, the patient’s nose has taken upon a straighter appearance with a narrowing of the nasal bones. The alar bases have been modified and narrowed to correctly fit the patient’s face. There is no appreciable scarring from the alar base incisions and the alar-facial sulcus has been maintained.

|  |

| ( Figure 8 A ) | ( Figure 8 B ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 8 C ) | ( Figure 8 D ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 8 E ) | ( Figure 8 F ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 8 G ) | ( Figure 8 H ) |

|  |

| ( Figure 8 I ) | ( Figure 8 J ) |

| |

| ( Figure 8 K ) | |

| (Figure 8 A-K) |

The patient is extremely satisfied with the overall appearance of his nose, strength in the nasal tip and his improved breathing from both nostrils. He feels much more confident with his new nose and is very pleased with the final results.

REFERENCES

1. Bennett GH, Lessow A, Song P, Constantinides M. The long-term effects of alar base reduction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Mar-Apr 2005;7(2):94-97.

2. Weir RF. On restoring noses without scarring the face. N Y Med J. 1892(56):449-454.

3. Kridel RW, Castellano RD. A simplified approach to alar base reduction: a review of 124 patients over 20 years. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Mar-Apr 2005;7(2):81-93.

4. Joseph J, ed Nasenplastik und sostige Gesichtsplastik nebst einem Anhang uber Mamaplastik. Leipzig, Germany: Curt Koitzsch; 1931.

5. Aufricht G. A few hints and surgical details in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1943;57:317-335.

6. Willis AE, 2nd, Costa LE, 2nd. Surgical management of the alar base. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. Sep 1995;3(2):65-77.

7. Tardy ME, Jr., Patt BS, Walter MA. Alar reduction and sculpture: anatomic concepts. Facial Plast Surg. Oct 1993;9(4):295-305.

8. Bruintjes TD, van Olphen AF, Hillen B, Huizing EH. A functional anatomic study of the relationship of the nasal cartilages and muscles to the nasal valve area. Laryngoscope. Jul 1998;108(7):1025-1032.

9. Ali-Salaam P, Kashgarian M, Davila J, Persing J. Anatomy of the Caucasian alar groove. Plast Reconstr Surg. Jul 2002;110(1):261-266; discussion 267-271.

10. Adamson PA, Van Duyne JM. Alar base refinement. Aesthetic Plast Surg. Nov 2002;26 Suppl 1:S20.

11. Han SK, Lee DG, Kim JB, Kim WK. An anatomic study of nasal tip supporting structures. Ann Plast Surg. Feb 2004;52(2):134-139.

12. Rohrich RJ, Hoxworth RE, Thornton JF, Pessa JE. The pyriform ligament. Plast Reconstr Surg. Jan 2008;121(1):277-281.

13. Hur MS, Youn KH, Hu KS, et al. New anatomic considerations on the levator labii superioris related with the nasal ala. J Craniofac Surg. Jan 2010;21(1):258-260.

14. Jewett BS. Repair of small nasal defects. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. May 2005;13(2):283-299, vi.

15. Lee J, White WM, Constantinides M. Surgical and nonsurgical treatments of the nasal valves. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Jun 2009;42(3):495-511.

16. Sheen JH, Sheen AP. Aesthetic rhinoplasty. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo.: Quality Meical Pub.; 1998.

17. Larrabee WF, Jr. Facial analysis for rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Nov 1987;20(4):653-674.

18. Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Deutsch CK. Objective assessment of standard nostril types–a morphometric study. Ann Plast Surg. Nov 1983;11(5):381-389.

19. Crumley RL. Aesthetics and surgery of the nasal base. Facial Plast Surg. Winter 1988;5(2):135-142.

20. Guyuron B, Behmand RA. Alar base abnormalities. Classification and correction. Clin Plast Surg. Apr 1996;23(2):263-270.

21. Powell N, Humphreys B. Proportions of the aesthetic face. New York: Thieme-Stratton; 1984.

22. Silver WE, Sajjadian A. Nasal base surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Aug 1999;32(4):653-668.

23. Warner JP, Chauhan N, Adamson PA. Alar soft-tissue techniques in rhinoplasty: algorithmic approach, quantifiable guidelines, and scar outcomes from a single surgeon experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. May-Jun 2010;12(3):149-158.

24. Tebbetts JB. Primary rhinoplasty : a new approach to the logic and the technicques. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

25. Porter JP, Olson KL. Analysis of the African American female nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. Feb 2003;111(2):620-626; discussion 627-628.

26. Sim RS, Smith JD, Chan AS. Comparison of the aesthetic facial proportions of southern Chinese and white women. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Apr-Jun 2000;2(2):113-120.

27. Bernstein L. Esthetic anatomy of the nose. Laryngoscope. Jul 1972;82(7):1323-1330.

28. Gilbert SE. Alar reductions in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Jul 1996;122(7):781-784.

29. Rees TD. Aesthetic plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1980.

30. Bernstein L. Rhinoplasty for the Negroid nose. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. Oct 1975;8(3):783-795.

31. McCarthy JG, Wood-Smith D. Rhinoplasty. In: McCarthy JG, ed. Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990.

32. Adamson PA, Oakley S, Tropper GJ, McGraw BL. Analysis of alar base narrowing. American Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 1990(7):239-243.

33. Patel AD, Kridel RW. African-American rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. May 2010;26(2):131-141.

34. McKinney PW, Mossie RD, Bailey MH. Calibrated alar base excision: a 20-year experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. May 1988;12(2):71-75.

35. Gruber RP, Freeman MB, Hsu C, Elyassnia D, Reddy V. Nasal base reduction: a treatment algorithm including alar release with medialization. Plast Reconstr Surg. Feb 2009;123(2):716-725.

36. Gruber RP, Freeman MB, Hsu C, Elyassnia D, Reddy V. Nasal base reduction by alar release: a laboratory evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. Feb 2009;123(2):709-715.

37. Bertossi D, Albanese M, Malchiodi L, Procacci P, Nocini PF. Surgical alar base management with a personal technique: the tightening alar base suture. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Jul-Aug 2007;9(4):248-251.

38. Foda HM. Nasal base narrowing: the combined alar base excision technique. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Jan-Feb 2007;9(1):30-34.

39. Cinelli JA. Calibrated Weir operation. Arch Otolaryngol. Aug 1961;74:189-191.

40. Mazzola RF. Secondary unilateral cleft lip nose: the external approach. Facial Plast Surg. Oct 1996;12(4):367-378.

41. Adamson PA. Alar base reduction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. Mar-Apr 2005;7(2):98.

42. Egan KK, Kim DW. A novel intranasal stent for functional rhinoplasty and nostril stenosis. Laryngoscope. May 2005;115(5):903-909.

43. Toriumi DM. New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast Surg. May-Jun 2006;8(3):156-185.

FIGURE LEGEND

Figure 1. The nasal base view demonstrating the nostril sill (short solid line), interalar distance (long solid line) and alar-facial junction (arrow).

Figure 2. The width of the lobule or superior one-third of the base view (solid line) is about 75 percent of the entire nasal base width (dashed line).

Figure 3. When evaluating the alar base on frontal view, the width should approximate the intercanthal distance (dashed lines). In this patient, the alar base is asymmetrical, with slightly more alar width on the right side. The surgeon could consider a unilateral alar base reduction on the right side.

Figure 4. Traditional markings for alar base reduction. These markings are made at the nasolabial junction in the columella midline, at the lateral-most points of each alar-facial groove, and at the sill crease.

Figure 5 (A&B). A. Pre-operative nasal base view of patient with a platyrhine Asian nose. The patient has both a long nasal sill and excessive alar flare. B. 2 year post-operative nasal base view after both nostril sill excisions (internal reduction) and alar wedge excisions (external reduction).

Figure 6. 4-month post-operative view of patient from Figure 2. Slight nostril sill notching (arrow) after only an internal alar base reduction to remove excess sill.

Figure 7 (A-K). Pre-operative rhinoplasty photographs for analysis and surgical planning

Figure 8 (A-K). 2 year follow-up post-operative rhinoplasty photographs