Rhinoplasty – surgery to reshape the nose—is a common procedure for both cosmetic and functional requests.

Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Address all correspondence to Dr. Daniel G. Becker, Dept. of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Univ. of Pennsylvania Hospital, 3400 Spruce Street, 7 Silverstein, Philadelphia PA 19104; beckermailbox@aol.com

ABSTRACT: Rhinoplasty—surgery to reshape the nose—is a common procedure for both cosmetic and functional requests. In this article, the author provides an overview of rhinoplasty, with special emphasis on the surgical anatomy and preoperative analysis of appearance. A review of some of the surgical techniques at the disposal of the rhinoplasty surgeon is also provided and illustrated with patient examples.

KEYWORDS: rhinoplasty, cosmetic, nasal obstruction, anatomy, nasal analysis, aesthetic ideal

I. INTRODUCTION

Cosmetic rhinoplasty is surgery to reshape the nose. In the United States, approximately 50,000 cosmetic rhinoplasties are performed each year. Common requests include making a nose smaller, reducing the bridge of the nose, narrowing the nose, making changes to the nasal tip, and lifting a droopy tip. Patients seeking treatment also include those whose noses are too short, too long, too narrow, too wide, twisted, and so forth. Also, a significant number of patients who suffer nasal fractures later seek rhinoplasty.

A number of patients desire improvement in their nasal breathing and their nasal appearance. Fortunately, a number of procedures (including noncosmetic, or functional rhinoplasty) allow the surgeon to substantially improve nasal breathing at the same time that cosmetic changes are made.

Patients who do not like the way their noses look and who are in good physical and mental health are eligible for a rhinoplasty consultation. The next step is to meet with a skilled surgeon to see if surgery can meet their expectations.

Rhinoplasty is most common in the late teens, twenties, and thirties. A significant number of patients in their forties and fifties also seek rhinoplasty. The oldest patient for whom the author has performed a cosmetic rhinoplasty was in her seventies.

Most rhinoplastic surgeons prefer to wait until an individual has completed his or her growth spurt before performing rhinoplasty. This means about age 16 for girls, and a little later for boys. Of course, this is a generalization—it is very important to take into consideration the individual’s emotional and social maturity level.

Rhinoplasty is outpatient surgery. It is typically performed with the patient under general or sedation anesthesia. Under sedation, the nose and surrounding areas will be numb, and the patient will drift in and out of sleep. With general anesthesia, the patient will be asleep for the entire procedure. Depending on the complexity, a rhinoplasty takes approximately 1-2 hours.

It has been the author’s experience that there is not typically much pain or nausea in the recovery period. After-surgery pain is usually well-controlled with amild narcotic. A skillful anesthesia team is essential to provide expert outpatient anesthesia that keeps after-surgery nausea to a minimum.

If the surgeon makes changes only to the outside of the nose, then there is no nasal packing. But if the surgeon does some work for nasal breathing that requires straightening the septum, then small nasal packs may be placed inside each nostril and are usually removed the next morning.

Patients are advised to take a week off from work after surgery. They report that recovery is uneventful. The patients’ main job after surgery is just to rest. Most surgeons provide their patients with detailed after-surgery instructions.

The patient will notice some swelling and bruising around the eyes that typically begins to disappear within a few days. Resting with the head elevated helps speed this process. The surgeon will typically remove the nasal bandage in about 6 days. If dissolvable stitches are used, there are no stitches to remove. After removal of the small nasal bandage (or “splint”), most patients are presentable in public. Most of the author’s patients return to work the day after nasal splint removal. There are restrictions on activity for a few more weeks after that. And of course, there is continued healing and reduction of swelling that continues to take place, quickly at first and then gradually for at least a year.

While the major changes will be apparent immediately, the more subtle changes do take time to become apparent. This is the case because healing is a relatively slow, gradual process. The author typically advises patients that it takes one year for 80% of the healing to take place.

To the extent that it is possible, it is essential that the surgeon understands what the patient wants, and that the patient understands what the surgeon is planning. With this in mind, the surgeon should have a clear conversation with the patient on this subject. Also, the author reviews computer imaging with most patients to improve communication, to make sure the patient and surgeon are “on the same page.”

With computer imaging, the surgeon shows the patient an imaging result that is the goal for surgery, with the objective of making sure that the patient agrees with the goal. The patient understands that this is not a guarantee but rather a shared goal.

Computer imaging is a very helpful way to communicate surgical goals. It is important for the surgeon to know what the patient wants to accomplish, and the patient must know what the surgeon envisions as a goal for the surgical result. Computer imaging is extremely useful for communicating this information.

Careful presurgical planning is an important part of rhinoplasty. The author typically “performs” each surgery at least 6 times: first (mentally) during the patient’s first office visit, again upon additional refl ection, a third time after careful review of the preoperative photography, a fourth time just prior to the actual surgery, a fifth time is the actual surgery, and then the sixth times (and possibly more) after the surgery as review, “postsurgery analysis.”

The author advocates a conservative approach to rhinoplasty, avoiding over-aggressive resection maneuvers, focusing on maintaining structural support, and seeking a natural unoperated appearance.

II. ANATOMY OF THE NOSE

Skillful, experienced rhinoplasty surgeons seek to understand the underlying anatomic causes of the various problems creating an undesired nasal appearance. Understanding the anatomic cause provides a guide to the correct correction approaches.

The anatomy is the underlying reason that a nose looks as it does. Accurate assessment of the patient’s anatomy, whether for a first-time rhinoplasty or for a revision rhinoplasty, allows the surgeon to develop a rational and realistic surgical plan. Recognizing variations in the anatomy is critical to guide the surgeon to the correct approach for a particular patient.

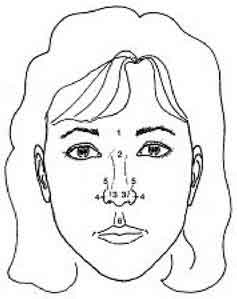

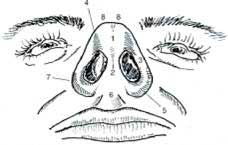

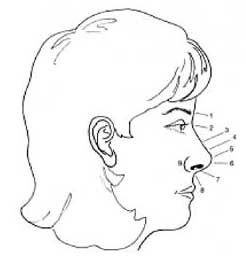

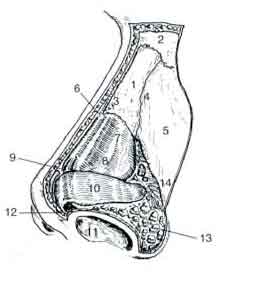

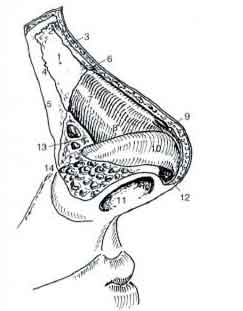

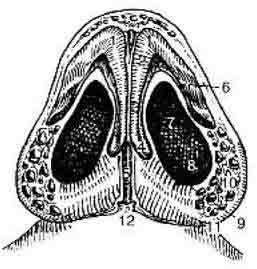

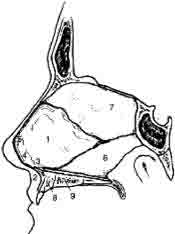

A simplified diagrammatic overview of nasal anatomy is presented here (Figs 1-8). Figures 1-4 show the nose from four standard viewpoints; impor‑tant surface landmarks are marked. Figures 5-7 show the internal anatomy, beneath the skin. The diagrams show the surface anatomy and the structural (i.e., beneath the surface) anatomy of the nose.

FIGURE 1. Frontal. 1: glabella, 2: nasion, 3: tip-defining points, 4: alar-sidewall, 5: supra-alar crease, 6: philtrum.

III. The Ideal Nose

The “ideal” nose is one that is in harmony with the other favorable features of a patient’s face. The “ideal” shape for a male or female nose is an aesthetic concept that has its roots in our perception of beauty.

FIGURE 2. Base. 1: infratip lobule, 2: columella, 3: alar sidewall, 4: facet or soft-tissue triangle, 5: nostril sill, 6: columella-labial angle or junction, 7: alar-facial groove or junction, 8: tip defining points.

FIGURE 3. Lateral. 1: glabella, 2: nasion, nasofrontal angle, 3: rhinion (osseocartilaginous junction), 4: supratip, 5: tip-defining points, 6: infratip lobule, 7: columella, 8: columella-labial angle or junction, 9: alar-facial groove or junction.

FIGURE 4. Oblique. 1: glabella, 2: nasion, nasofrontal angle, 3: rhinion, 4: alar sidewall, 5: alar-facial groove or junction, 6: supratip, 7: tip-defining point, 8: philtrum.

FIGURE 5. Oblique. 1: nasal bone, 2: nasion (nasofrontal suture line), 3: internasal suture line, 4: nasomaxillary suture line, 5: ascending process of maxilla, 6: rhinion (osseocartilaginous junction), 7: upper lateral cartilage, 8: caudal edge of upper lateral cartilage, 9: anterior septal angle, 10: lower lateral cartilage: lateral crus, 11: medial crural footplate, 12: intermediate crus, 13: sesamoid cartilage, 14: pyriform aperture.

FIGURE 6. Lateral. 1: nasal bone, 2: nasion (nasofrontal suture line), 3: internasal suture line, 4: nasomaxillary suture line, 5: ascending process of maxilla, 6: rhinion (osseocartilaginous junction), 7: upper lateral cartilage, 8: caudal edge of upper lateral cartilage, 9: anterior septal angle, 10: lower lateral cartilage: lateral crus, 11: medial crural footplate, 12: intermediate crus, 13: sesamoid cartilage, 14: pyriform aperture.

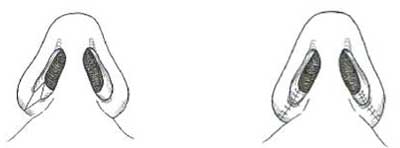

FIGURE 7. Base. 1: tip-defining point, 2: intermediate crus, 3: medial crus, 4: medial crural footplate, 5: caudal septum, 6: lateral crus, 7: naris, 8: nostril floor, 9: nostril sill, 10: alar lobule, 11: alar-facial groove or junction, 12: nasal spine.

FIGURE 8. The septum is an important structure in septorhinoplasty, its anatomy is shown here. 1: quadrangular caratilage, 2: nasal spine, 3: posterior septal angle, 4: middle septal angle, 5: anterior septal angle, 6: vomer, 7: perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone, 8: maxillary crest, maxillary component, 9: maxillary crest, palatine component.

This cannot be completely boiled down to lines and numbers—there is always an indescribable “artistic” element. However, by studying beauty, and faces that are universally felt to be beautiful, artists and plastic surgeons can arrive at some guidelines or proportions that represent the “aesthetic ideal.” Leonardo da Vinci was among the first to make such studies of beauty and aesthetic proportions. He and other artists have been joined in this pursuit by facial plastic surgeons, whose profession entails understanding beauty and then making changes that enhance the beauty of their patients.

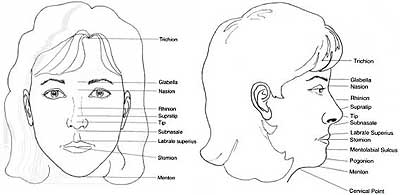

The figures that follow show diagrammatically the ideal dimensions of the nose (Table 1, Figs. 9-17). This aesthetic “ideal” is simply a goal or a frame of reference that must be modified to reflect the realities of a particular patient’s facial features.

The lines and measurements outlined here are a general guideline for facial plastic surgeons that is applied to each patient individually. When a patient presents for a rhinoplasty consultation, the experienced surgeon makes mental note of a “firstimpression”—e.g., too big, twisted, large hump, an overoperated or revision nose. This first impression is important, because the odds are that this is what is bothersome to the patient as well. Often the surgeon will also ask the patient early on what it is that bothers the patient about his or her nose.

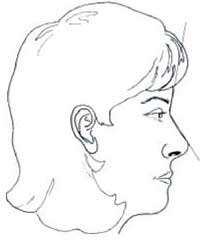

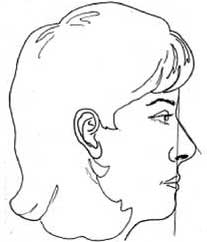

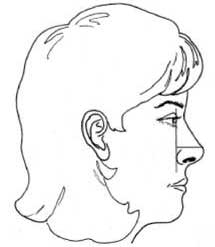

The surgeon considers the nose from the front. He determines whether the nose is twisted or straight, narrow, normal, or of excessive width, whether the nasal tip is bulbous, asymmetric, or otherwise abnormal. He also makes note of the skin quality—thin, medium, or thick.

The surgeon considers the nose from the side and determines whether the nose in profile is too long or too short, whether the profile has a hump, if it is too scooped, or if it is a pleasant and desirable outline that fits the patient’s face. The surgeon determines if the tip of the nose sticks out too far from the face (“overprojected”), if the nose is too small (“underprojected”), or if it is just right. The surgeon also examines the nose to see if there is too much nostril showing.

Table 1. Surface Angles, Planes, and Measurements

Table 1. Surface Angles, Planes, and Measurements

| Facial thirds | Upper third: trichion to glabella |

| Middle third: glabella to subnasale | |

| Lower third: subnasale to menton | |

| Horizontal fifths | Five equally divided vertical segments of the face |

| Frankfort plane | Plane defined by a line from the most superior point of auditory canal to most inferior point of infraorbital rim. |

| Nasofrontal angle | Angle defined by glabella-to-nasion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal 115-130° (within this range, larger angle more favorable in females, smaller angle more favorable in males). |

| Nasofacial angle | Angle defined by glabella-to-pogonion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal 30-40°. PEARL: “normal” projection with a 3-4-5 triangle described by Crumley (see below; nasofacial angle of 36°). |

| Nasomental angle | Angle defined by nasion-to-tip line intersecting with tip-to-pogonion line. Normal 120-132°. |

| Relationship of lips: | |

| To nasomental line | Upper lip 4 mm behind, lower lip 2 mm behind line from nasal tip-to-menton |

| To subnasale-to-pogonion line | Upper lip 3.5 mm anterior, lower lip 2.2 mm anterior |

| Mentocervical angle | Angle defined by glabella-to-pogonion line intersecting with menton-to-cervical point line. |

| Nasolabial angle | Angle defined by columellar point-to-subnasale line intercepting with subnasale-to-labrale superius line; normal 90-120° (within this range, larger angle more favorable in females, smaller angle more favorable in males). |

| Columellar show | Alar-columellar relationship as noted on profile view, 2-4 mm of columellar show is “normal.” |

| Nasal projection | Forward protrusion of nasal tip from face. One way to measure this is Goode’s method: a line drawn through the alar crease, perpendicular to the Frankfurt plane; the length of a horizontal line drawn from the nasal tip to the alar line (alar point-to-nasal tip line) divided by the length of the nasion-to-nasal tip line. Normal is 0.55-0.60. |

| Powell & Humphries “Aesthetic Triangle” | Nasofrontal, 115-130°; nasofacial, 30-40°; nasomental, 120-132°; mentocervical, 80-95° |

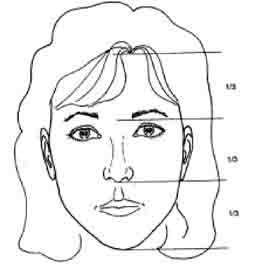

FIGURES 9-10. Major facial reference points. These figures will be necessary for the reader to understand the definitions and angles presented later on this page.

FIGURE 11. Facial thirds. Upper third: trichion to glabella; middle third: glabella to subnasale; lower third: subnasale to menton.

Rhinoplasty THE IDEAL NOSE – Major Facial Reference Points

FIGURE 12. Horizontal fifths. Five equally divided vertical segments of the face.

The surgeon considers the nose from all angles, including from the bottom. Important informa- surgery. Examination of the nose also includes paltion about the nasal anatomy is learned from this pation—feeling the nose tells the surgeon essential examination and is critical to planning a successful information about what must be done.

FIGURE 13. Nasofrontal angle is an angle defined by glabella-to-nasion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal 115-130° (within this range, a larger angle more favorable in females, smaller angle more favorable in males).

FIGURE 14. Nasofacial angle: angle defined by glabella-to-pogonion line intersecting with nasion-to-tip line. Normal 30-40°. “Normal” projection with a 3-4-5 triangle described by Crumley (see below) gives a nasofacial angle of 36°.

FIGURE 15. Nasal projection. Forward protrusion of nasal tip from face. In Goode’s method, a line is drawn through the alar crease, perpendicular to the Frankfurt plane. The length of a horizontal line drawn from the nasal tip to the alar line (alar point-to-nasal tip line) divided by the length of the nasion-to-nasal tip line defines projection. Normal is 0.55-0.60.

The complete assessment of the patient’s nose, in combination with an understanding of the patient’s requests, guides the surgeon to a surgical plan.

FIGURE 16. Nasolabial angle. The normal range of the nasolabial angle is 90-120°. Within this range, a more obtuse angle is favored in women than in men.

FIGURE 17. Nasomental angle. The nasomental angle has a normal range of 120-132°s. Along with the nasofrontal angle (Fig. 13) and the nasofacial angle (Fig. 14), it is one of an important set of analysis angles known as Powell & Humphries’ “Aesthetic Triangle.”

IV. INCISIONS AND APPROACHES

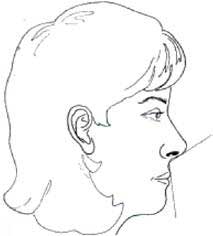

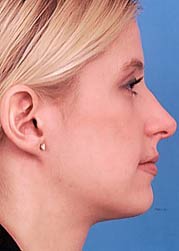

The two approaches to rhinoplasty are the endonasal or “closed” rhinoplasty (all incisions hidden inside the nose) and the external or “open” rhinoplasty (all but one small incision are inside the nose). In open rhinoplasty there is one small incision across the columella (the skin between the nostrils). This incision is generally extremely difficult to see, and is only 3 or 4 mm long (Fig. 18).

Because every nose is different and has unique surgical requirements, the closed approach may be more suitable for some noses, while the open approach may be more suitable for others. There is an area of overlap—that is to say, there are some noses that may be done through either the open or the endonasal approach. Some surgeons perform predominantly one approach as a result of their personal experience and training, while other surgeons are adept at both.

Fortunately, there are no major disadvantages to either approach. However, each approach has special advantages for specific situations. Because every nose is different and has unique surgical requirements, the pa‑tient should expect his or her surgeon to explain which approach should provide the best outcome. When the patient is interested, the surgeon should be willing to discuss the technical aspects of the planned surgery.

FIGURE 18. In open rhinoplasty there is one small incision across the columella (the skin between the nostrils). This incision—across the tissue between the nostrils—is generally extremely difficult to see, and is only 3 or 4 mm long. The patient shown here (a, b preoperative, c, d postoperative) had an open rhinoplasty. The incision may be seen on the postoperative base view (d).

V. SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Techniques are simply tools available to perform a task. In tennis, a player needs a forehand and a backhand, a strong serve, a net game, and so forth. However, having these tools alone is not enough—the player must string together the right combination of strokes in a particular situation to win a point, game, set, and match. In ballet, computer programming, and numerous other endeavors, similar principles apply.

The art of rhinoplasty requires that the rhinoplasty surgeon master numerous individual techniques. However, the surgeon must go beyond this technical task to have the skill and judgment to pick the right techniques for a particular situation and put it all together to achieve a successful rhinoplasty.

Following are selected techniques that are commonly employed in rhinoplasty. Diagrams and photo-graphs are provided for demonstration purposes.

V. (A) Taking Down the Hump

Patients often request correction of their “nasal bump.” These patients typically desire a conservative profile change, creating a nose that is in harmony with the rest of their facial features.

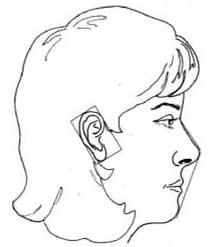

The nasal hump is composed of cartilage and bone. There are several methods of taking down the nasal hump; one approach is described here (see Fig. 19).

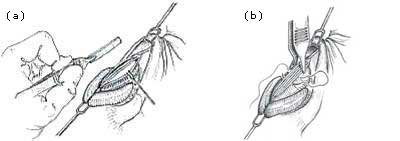

FIGURE 19. An en bloc (“in one piece”) resection of the nasal hump is author’s preferred approach. In this method, the cartilage of the hump is incised with a scalpel (a). This creates a “joint” at the junction of the bone and cartilage, shown here. The bone knife or “osteotome” is then seated at the bone-cartilage junction (b). A gentle tap-tap technique is used to advance the osteotome through the bone in the desired path (c). The bone-cartilage hump are removed in one piece (en bloc).

When the patient is asleep but before being injected with local anesthesia, the surgeon may mark the skin of the nasal bridge as a guide in visualizing the precise amount of the hump to be removed. The surgeon will have predetermined the amount of reduction needed, but the markings are a helpful guide. When computer imaging has been performed, the surgeon reviews the imaging goal before surgery and may have the photos in the room as an additional guide.

An en bloc (“in one piece”) resection of the nasal hump is the author’s preferred approach. In this method, the cartilage of the hump is incised with a scalpel. This creates a “joint” at the junction of the bone and cartilage, as shown.

The bone knife or “osteotome” is then seated at the bone-cartilage junction as illustrated in the diagrams (the osteotome is extremely sharp, so it cuts through the bone easily). A gentle tap-tap technique is used to advance the osteotome through the bone in the desired path. The bone-cartilage hump are removed in one piece (en bloc).

The surgeon carefully examines the patient’s nose and the bone-cartilage hump that has been removed. This careful evaluation guides the next step—fi ne tuning of the profile with additional excision of small amounts of cartilage, and filing or rasping of the bone to smooth it (see below).

Rhinoplasty SURGICAL TECHNIQUES – Rasping and Osteotomies

V.B. Rasping

Reducing or smoothing the bony hump may be undertaken with a surgical file or rasp. This is a commonly used approach. Some surgeons—including the author—use a powered rasp because they feel it is more precise. These surgeons believe that with time the use of the powered rasp will increase as awareness grows. The author made great efforts worldwide to popularize the use of powered instrumentation for rasping in rhinoplasty.9

V.C. Osteotomies

Osteotomies refer to “cutting” or “breaking” the nasal bones. This is not necessary in all rhinoplasties.

Osteotomies are typically necessary when the nasal hump has been reduced. They are also often necessary to narrow an over-wide nose or to improve a twisted nose.

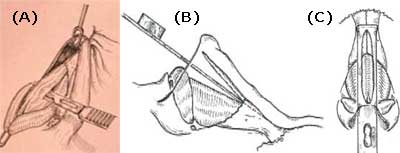

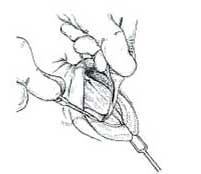

There are several approaches to osteotomies; one approach is described here (Fig. 20).

The bone is cut in the middle with a “back cut” known as a medial osteotomy. Then, a small bone knife or osteotome is placed at the edge of the bone as shown. A gentle tap-tap technique is used to advance the osteotome along the planned path, outlined in this diagram. Now the bone is cut and may easily be shifted as needed.

Becker et al. have described small specialty osteotomes for minimally traumatic osteotomies.¹² Re-search has suggested that these “Becker” osteotomes and other osteotomes of similar small size are less traumatic than larger, bulkier osteotomes and may result in less bruising and faster healing time.

FIGURE 20. The bone is cut in the middle with a “back cut” known as a medial osteotomy (a). Then, a small bone-knife or osteotome is placed at the edge of the bone as shown (b). A gentle tap-tap technique is used to advance the osteotome along the planned path, outlined on the diagram. Now the bone is cut and may easily be shifted as needed.

Rhinoplasty SURGICAL TECHNIQUES – Spreader Grafts and Tip Work

V.D. Spreader Grafts

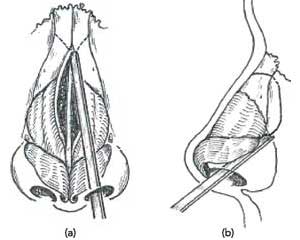

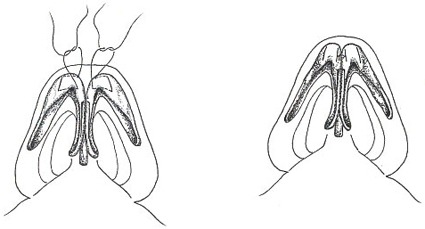

Spreader grafts are rectangular strips of cartilage placed between the septum and the upper lateral cartilages (Fig. 21).

Spreader grafts are helpful in circumstances when widening of the middle third is needed, a relatively uncommon but obvious circumstance. Also, spreader grafts can provide important additional support of the middle third of the nose in certain types of patients. This sort of patient has short nasal bones, long weak upper lateral cartilages, thin skin, and a narrow nose. Other patients who may need the additional support of spreader grafts include those who require a large hump reduction.

V.E. Tip Work

A tip that is too big or too full draws attention to itself and may detract from the patient’s appearance. Many patients request refinement of the bulbous nasal tip so that it is proportional to the rest of their nose and their face.

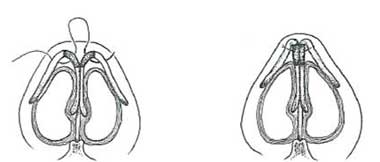

Suture techniques represent a conservative and reliable way to make changes to the nasal tip. Suture techniques can be instrumental in refining a bulbous nasal tip (Fig. 22). Suture techniques can also facilitate tip elevation (projection and rotation) (Fig. 23). Because there is no resection of tissue with this technique, it is felt that these techniques are relatively safe when performed by a skillful surgeon.

FIGURE 21. (a,b) Spreader grafts are rectangular strips of cartilage placed between the septum and the upper lateral cartilages.

Rhinoplasty SURGICAL TECHNIQUES – Spreader Tip Work Continued

Cephalic resection is a technique that can help achieve refinement or “narrowing” of the nasal tip. In this technique, a resection of a portion of the tip cartilage along the upper edge is undertaken. Known by surgeons as cephalic resection, this technique is an-other important and useful method for refining the bulbous tip (Fig. 24).

When performing a cephalic resection, rhinoplasty surgeons must carefully judge how much to take and how much to leave behind. It is critical that the surgeon not take too much. There are general guidelines of how much is too much, but each patient is different, and the strength of each patient’s cartilage must be carefully considered. If a patient has thin, soft, weak cartilage, very little if any cephalic resection should be undertaken.

Tip grafts can be useful in achieving a number of different effects, depending upon how the surgeon shapes and places the graft. A tip graft is typically made from the patient’s own cartilage, preferably taken from the nasal septum during septoplasty. Tip grafts can help create additional nasal tip refinement. Depending upon its placement, a tip graft can also be helpful in projecting the nose, in lengthening the nose, or both. Tip grafts can also be helpful in revision rhinoplasty (Fig. 25).

FIGURE 21. (c,d) Spreader grafts can provide important support of the middle third of the nose in certain types of patients. Patients who may need the additional support of spreader grafts include those undergoing hump reduction and who have small nasal bones and long upper lateral cartilages.

Rhinoplasty SURGICAL TECHNIQUES – Base Resection

A columellar strut consists of a rectangular piece of cartilage placed between the medial crura of the tip cartilages. The surgeon may place a strut if the nasal tip needs additional support or strength. This strut provides additional strength to the tip and may provide some degree of tip elevation (projection and rotation).

Plumping grafts can be a helpful technique if the junction of the nose to the upper lip is retracted or “acute,” which may be modified by placing “plumping” grafts beneath the skin in this location. Throughan incision inside the nose, bits of the patients own cartilage (usually taken from the nasal septum) may be placed at the base of the naso-labial angle. This can improve an overly sharp angle there. This sharp angle is often seen in an “aging” nose (Fig. 26).

V.F. Base Resection

Base resection is a technique that is useful if the nose is too wide at the bottom. If this is the case, a portion of the nostril at the base may be removed to narrow it. This is called an alar base resection (Fig. 27).

FIGURE 22. A bulbous tip may be addressed with suture techniques. The suture technique illustrated here was used in this patient. (a,b) Preoperative, (c,d) postoperative.

FIGURE 23. The suture technique known as “lateral crural steal” can be useful in lifting the tip (projecting and rotating the tip). This technique was used in this patient to correct her droopy nose abnormality. (a,b) Preoperative, (c,d) postoperative.

FIGURE 24. In cephalic resection, a resection of a portion of the

FIGURE 25. Tip graft can be an extremely useful graft technique tip cartilage along the upper edge is undertaken. when correcting problems of the nasal tip.

VI. SPECIFIC COSMETIC REQUESTS

VI.A. The Nasal Hump

Patients often request correction of their “nasal bump.” These patients typically desire a conservative profile change, creating a nose that is in harmony with the rest of their facial features (Fig. 28).

VI.B. The Bulbous Tip

A tip that is too big or too full draws attention to itself and may detract from the patient’s appearance. Many patients request refinement of the bulbous nasal tip so that it is proportional to the rest of their nose and their face (Fig. 22). A variety of different techniques may be used to address a bulbous nasal tip.

FIGURE 26. Plumping grafts can be a helpful technique if the junction of the nose to the upper lip is retracted or “acute.” This may be modified by placing “plumping” grafts (a-c).

FIGURE 27. Base resection can be a helpful technique to narrow the nose in specific anatomic situations. (a) Preoperative, (b) post-operative.

FIGURE 28. The nasal hump (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VI.C. The Broken Nose

After a nasal fracture, a patient’s nose may be twisted to one side or the other. Also, the patient may have a new “bump”—this is called a “saddle nose” or “boxer’s nose” deformity. A “before” and “after” example is shown in Figure 29.

FIGURE 29. The broken nose (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VI.D. The Twisted Nose

The twisted nose is one of the more technically challenging problems in rhinoplasty, requiring an experienced and skillful rhinoplasty surgeon. In the hands of an experienced and skillful surgeon, significant improvement is usually possible (Fig. 30). Sometimes the nose can be made completely straight; however, the patient should expect some deviation to persist.

FIGURE 30. The twisted nose (a,b) preoperative, (c,d) postoperative.

VI. E. Overprojection and Underprojection of the Nasal Tip

The nose that extends too far from the face (think Cyrano de Bergerac or Pinocchio after lying) is called “overprojected” (Fig. 31). The nose that doesn’t extend far enough from the face (think Pinocchio telling the truth) is underprojected. Correction of under-projection is a more common request of Asian and African-American patients.

VI.F. The Droopy Nose

Time and gravity affect all parts of our bodies, including the nose. The nose often droops as we get older. In these cases, lifting the droopy nose improves appearance and also makes the patient look younger (refer to Fig. 23).

FIGURE 31. Overprojection of the nasal tip (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VI.G. The Upturned Nose

The nose that is too upturned or “short” can be aesthetically displeasing (Fig. 32).

FIGURE 32. The upturned nose (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VI.H. Unique Nose

Because each person is different, each nose is unique. Certain types of problems are also relatively unique (Fig. 17). For example, this patient had congenitally misshapen tip cartilages that caused his nose to be extremely twisted and required specialized and advanced techniques.

VI.I. Finesse Rhinoplasty

Sometimes the patient has a request for a small refinement in the nose. This is known as a “finesse” rhinoplasty. These small changes require high levels of skill and expertise. An example is shown in Fig. 33.

FIGURE 33. Finesse rhinoplasty (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VI.J. Revision Rhinoplasty

Revision rhinoplasty is a problem that deserves an entire chapter of its own. The medical literature reports a revision rate of up to 1 in 10 or greater for rhinoplasty. Please refer to the selected references (Fig. 34).²”²”

VII. COMPLICATIONS

A complication—in its most simple form—is any-thing that makes the patient unhappy. If for any reason a patient is unhappy with the result, this might be considered a complication. This does not necessarily mean that the surgeon did something wrong, but may simply mean that despite his or her best efforts some undesired result occurred. Most surgeons will undertake any reasonable effort to satisfy a patient in this important surgery.

Surgery is not an exact science and results can-not always be anticipated. Despite the best efforts of a skillful surgeon, complications still occur. Theliterature reports that as many as 10% of patients may require some form of revision surgery.

Patients often wish to know what they can do before surgery to decrease the risk of complications. A discussion of the potential complications is critical, so that the patient understands the small but real risks of a complication. The surgeon will give the patient instructions for before and after surgery, and the patient should be sure to follow them. However, although most complications are relatively minor and correctable, more serious and debilitating complications do occur.

A good surgeon is highly self-critical. There is a story told among rhinoplasty surgeons that a famous master rhinoplasty surgeon was asked, toward the end of a career in which he had performed many thousands of rhinoplasties, how many “perfect” rhinoplasties he had done. After some thoughtful reflection, he replied, “two.”

With this in mind, one can imagine that in many cases the surgeon may notice an imperfection that is amenable to correction, but the patient may not even notice it or may not be concerned by it.

There is no way for a patient to be certain that he or she won’t have a complication. Even if the surgeon does things well, a complication can occur. Just as an airplane can encounter unexpected turbulence, unan-ticipated technical problems can occur during surgery that can lead to a complication. Despite careful pre-operative analysis and meticulous attention to surgical detail, unacceptable results may still occur.

Cosmetic surgical procedures have been repeated successfully countless times and are dependable when executed by skillful, experienced surgeons. Plastic surgery is a combination of art and science, and as such can be subject to unpredictables—usually (but not always) minor in nature.

No surgical procedure should be taken lightly; a slight but real risk is involved in all surgery. Fortunately, the overwhelming majority of plastic surgery results are highly satisfactory and pleasing when accompanied by careful presurgical planning, meticulous surgery, and full patient cooperation.

FIGURE 34. Revision rhinoplasty (a) preoperative, (b) postoperative.

VIII. CONCLUSIONS

Rhinoplasty has the remarkable ability to make people feel better about themselves. Indeed, it is indisputable that rhinoplasty is a positive experience for the vast majority of patients. Many studies show that the great majority of rhinoplasty patients benefit psychologically from the operation.

But, why is rhinoplasty successful? In other words, why does it produce positive psychological benefits?

Many complex psychological explanations have been suggested for this, but one thinker on the subject maintained a more concrete opinion: “We should not underrate the importance of actual beauty … in human life.”

This philosopher went on to say: “Beauty can be a promise of complete satisfaction … our own beauty [or lack of it] will not only figure in the image we get about ourselves, but will also figure in the image others build up about us and which will be taken back again into ourselves. The body image is the result of social life.”

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1997.

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Philosophy and Principles of Rhinoplasty. In: Cummings et al., editors. Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 2 ed. Mosby Year Book, 2000.

- Tardy ME, Brown R. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose. New York: Raven Press, 1990.

- Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

- Toriumi DM, Mueller RA, Grosch T, Bhattacharyya TK, Larrabee WF. Vascular anatomy of the nose and the external rhinoplasty approach. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1996; 122:24-34.

- Ridley MB. Aesthetic facial proportions. In: Papel, Nachlas, editors. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Mosby-Year Book, 1992.

- Crumley RL, Lanser M. Quantitative analysis of nasal tip projection. Laryngoscope 1998; 98: 202-208.

- Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Rhinoplasty: a practical guide for surgical planning. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993; 91: 642-654, discussion 655-656.

- Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME. Powered instrumentation for dorsal nasal reduction. Facial Plast Surg 1997; 13(4):291-297.

- Larrabee WF Jr. Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Plast Clin North Am 1993; 1(1):23-38.

- Thomas JR. Steps for a safer method of osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 1987; 97(6):746-747.

- Becker DG, McLaughlin R, Mang A, Loevner LA. The lateral osteotomy in rhinoplasty: a clinical and radiographic rationale for the selection of osteotomes. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105:1806-1816.

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasalvault. Operative Tech Plast Reconstr Surg 1995; 2(1):16-30.

- Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984; 73(2): 230-237.

- Goode RL. Surgery of the incompetent nasal valve. Laryngoscope 1985; 95:546-555.

- Becker DG, Weinberger MS, Greene BA, Tardy ME. Clinical study of alar anatomy and surgery of the alar base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 123(8):789-795.

- Tardy ME, Patt BS, Walter MA. Alar reduction and sculpture: anatomic concepts. Facial Plast Surg 1993; 9(4):295-305.

- Tardy ME, Walter MA, Patt BS. The overprojecting nose: anatomic component analysis and repair. Facial Plast Surg 1993; 9(4):306-316.

- Toriumi DM. Surgical correction of the aging nose. Facial Plast Surg 1996; 12(2):205-214.

- Kamer FM, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, editor. Head and Neck Surgery—Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, 1998.

- Rees TD. Postoperative considerations and complications. In: Rees TD, editor. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1980.

- Thomas JR, Tardy ME. Complications of rhinoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J 1986; 65:19-34.

- Tardy ME, Cheng EY, Jernstrom V. Misadventures in nasal tip surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987; 20(4):797-823.

- Simons RL, Gallo JF. Rhinoplasty complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994; 2(4):521-529.

- Becker DG. Complications in rhinoplasty. In: Papel I, editor. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York: Thieme, 2002.

- Goin JM, Goin MK. Changing the body—psychological effects of plastic surgery. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1981.

- Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants