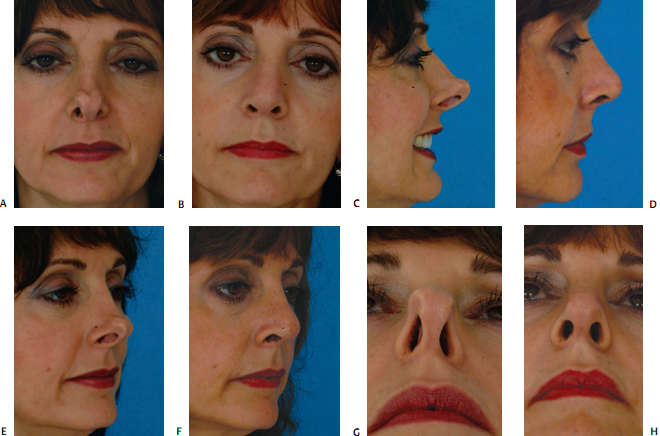

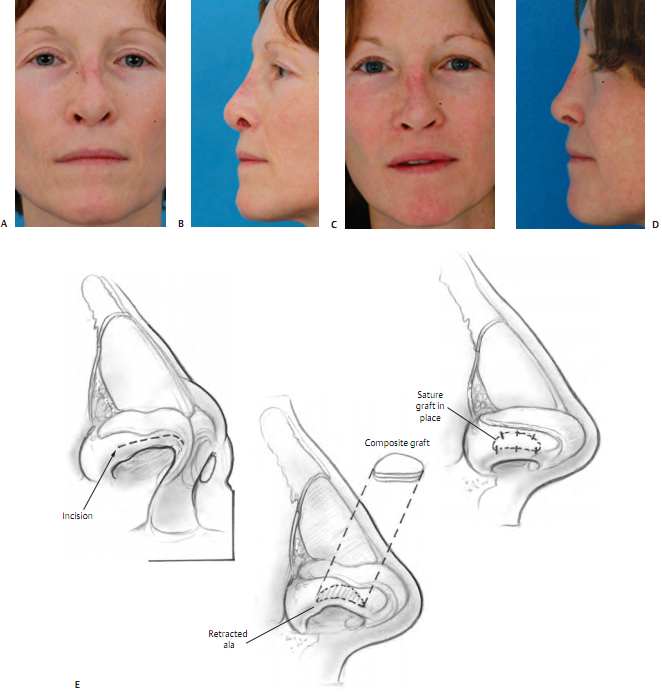

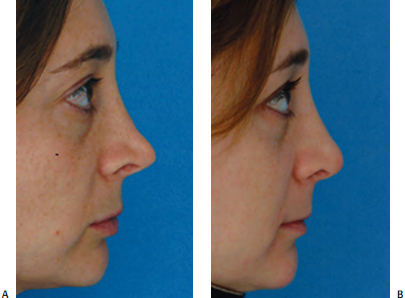

Revision rhinoplasty is a term that encompasses a wide spectrum of problems, from straightforward to complex. In an established revision practice, patients seeking con- sultation include many who have all but lost hope. Commonly, the experienced revision surgeon will find that significant improvement is possible (Fig. 18–1). However, to achieve success, it is important that the patient and sur- geon come to a realistic understanding of what can and cannot be accomplished. Verbal communication supple- mented by computer imaging helps the surgeon and patient arrive at a shared surgical goal.

The revision rhinoplasty patient needs an environment in which he or she will be able to develop and maintain trust. This environment is best created by dedicating one- self to revision surgery, by placing a strong emphasis on patient education, by taking the time necessary to answer the patient’s questions and concerns, and by being honest and plainspoken. The patient must feel that the surgeon has a passion for the operation and that the surgeon has dedicated him- or herself to the pursuit of excellence in nasal surgery, specifically revision surgery.

The revision patient is acutely aware that surgery is not an exact science and that complications can occur. The revision patient understands that complications also can occur in revision surgery; with this in mind, it is critically important that the surgeon show a special attention to risk management.

For many revision patients, life begins to revolve around their nose. It is important that patients be pre- pared for a shift in focus. They should be prepared to shift focus toward getting on with their lives after the impor- tant changes to their noses have been made.

The revision surgeon’s job does not end after surgery. If the result of a revision achieves the shared surgical goals, the surgeon should caution the patient to avoid the impulse to make additional small changes. The result should not become a “moving target.”

When there are problems that may benefit from addi- tional work, naturally, the revision surgeon addresses them forthrightly. Conversely, it is important that the patient give thoughtful consideration to the recommen- dation by the experienced revision surgeon that no fur- ther surgery should be contemplated. In this setting (as in all aspects of patient care) it is important that the sur- geon and patient have established a trusting relation- ship. Still, each patient ultimately bears a certain amount of responsibility for his or her own actions and decisions.

With the psychological, emotional, and technical fac- tors in mind, it is important that the revision surgeon approach the nose with an emphasis on risk management. Surgery is not an exact science, and the results are not always predictable. The surgical plan is designed to achieve the shared surgical goals with as little trauma as possible. The patient is reminded that complications can still occur and that not all complications are correctable.

Ultimately, success in revision rhinoplasty is based on well-developed judgment, wisdom, and accumulated knowledge and experience. Like most surgeries, revision rhinoplasty is both a science and an art. Skill comes from experience and wisdom, combined with a measure of talent. The revision surgeon must have a detailed understanding of the multiple anatomic variants encountered. The surgeon must also have accumulated the appropriate surgical tech- niques and experience. Specifically, the revision surgeon must acquire knowledge of the surgical alterations that occur and how to achieve an improvement or correction when the result is undesirable. This second skill set is acquired by careful follow-up of operated patients over time.

My personal philosophy of revision rhinoplasty focuses on achieving two essential goals. The first is to make the patient happy. Hand in hand is the second goal: for this to be their last nasal surgery. With these goals and these introductory thoughts in mind, in this chapter I will dis- cuss my personal philosophy and approach to revision rhinoplasty in terms of the psychological, nontechnical aspects, as well as the technical, surgical aspects. I will provide my general thoughts and a “run-through” of my current approach. Instead of a “theoretical” discussion, this chapter provides a “brass tacks” description of my approach to patients and my practical thoughts on the subject of the practice of revision rhinoplasty. It is my hope that this information will be useful to the reader.

Psychology of the Revision Rhinoplasty Patient

The revision patient is an individual who sought elective cosmetic surgery and, having understood the risks of a complication, is faced with a result that falls short of his or her expectations in some respect. All rhinoplasty surgeons have complications. The literature reports complication rates in the range of 8 to 15%. 1–8 Complications can occur despite surgery that has been technically well performed.

Regardless of the cause of a complication, it is important that complications be recognized and forthrightly addressed when they occur. Generally, a complication is correctible to some degree; on rare occasion, no improve- ment is possible.

Revision patients who seek care from their primary surgeon have retained confidence and trust in their sur- geon. Revision patients who seek care from someone other than their primary surgeon have, by definition, (and whether fairly or unfairly) lost confidence in their initial surgeon. These patients often require emotional support.

Revision patients often experience significant distress because of their unfavorable outcome. Generally speaking, these are people who sought elective, cosmetic rhino- plasty and understood that there was a risk of an unfavor- able result. Faced with an unsatisfactory result, some revision patients feel angry with themselves for “not hav- ing done more research.” Each time they look in the mir- ror, they are reminded of their “bad decision.” Having placed their trust in a surgeon, they now find it difficult to go through this process again. They seek not only to regain a favorable appearance but also to regain control.

It is fairly common that, early in an initial consultation for revision rhinoplasty, patients cry as they describe their condition to me. During the office visit, I directly address my observations as to the emotional effect that the unfa- vorable outcome has caused. I have found that patients appreciate knowing that I understand how they feel.

An occasional patient will benefit from psychiatric con- sultation as a part of his or her overall care. 9 I have found that patients have been responsive and have accepted this recommendation from me when I have made it.

Patients seek emotional support on their own, often from other patients. The emergence of Internet chat rooms and message boards has provided an outlet for patients to exchange ideas, information, and experiences. These patients provide non-professional reassurance and emo- tional support for each other—as people with a “shared experience”—as they proceed through the revision process. I have observed that this can be a favorable support, but more often it creates considerable anxiety in patients. Although this arena is largely outside of the surgeon’s con- trol, it is important to have some understanding that this sort of interaction occurs with increasing frequency.

For patients who have made a decision for surgery, we make available the opportunity to speak with former revision patients. This is optional. We explain that the intention is to provide an opportunity to find out abouta “typical” surgical experience from someone who “isn’t wearing a white coat.” We make it clear that this is a happy patient who has had successful revision rhino- plasty. I do not make this opportunity available until after a decision to proceed with surgery is made. I have found this offer to be useful in helping some patients understand the revision process from start to finish. In addition, it may help allay some of the new patient’s anxieties and worries, once the decision for surgery has been made.

Patient Consultation

Medical History, Photographic Documentation, Patient Goals

The patient is greeted and, if he or she has not done so already, is asked to fill out a detailed history form. He or she is then taken to the photography room by a nurse assistant, who takes digital photographs and escorts the patient to the examination room. The nurse then down- loads the photographs into the network computer.

I then meet the patient. I ask what he or she does not like about his or her nose and what the patient would like me to fix. After the patient explains the goals, I review any prior medical records. After a review of the patient’s med- ical history, I then perform an examination.

Aesthetic Nasal Examination

Detailed anatomic analysis of the nose is an essential first step in achieving a successful surgical outcome. My approach to rhinoplasty analysis in a primary rhinoplasty is well described. 10 I use this organized approach to aesthetic analysis for revision rhinoplasty as well (Table 18–1). The nasal analysis in revision rhinoplasty is made more complex by the fact of prior surgical intervention, with subsequent distortion of the pre-existing anatomy.

The first, critical factor is the skin–soft tissue enve- lope—its thickness, its quality, its integrity, and its mobil- ity in relation to the underlying nasal structures. As analysis proceeds, a critical question that guides examina- tion of each area is, “was it underresected, overresected, asymmetrically resected, or appropriately treated?” Any unoperated areas of the nose are identified. In addition, the presence of possible grafts or implants is considered throughout the examination. A partial list of specific con- siderations is discussed here.

For the bony dorsum, I examine the osteotomies and assess their position. Are they too high, normal, or too low? Is the bony dorsum straight or twisted, wide or nar- row? Will revision osteotomies be required? I look for the presence of open roof deformity or rocker deformity. In addition, I judge whether the bony hump was underre- sected or overresected. In addition, I palpate the bony hump for irregularities.

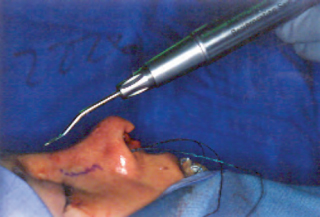

For the middle vault, I assess the middle vault width, with special attention directed to the presence of an inverted-V deformity. A narrow middle vault with an inverted-V deformity suggests a need to restore middle vault structural support (i.e., spreader grafts). I make a judgment as to whether the cartilaginous profile was underresected, overresected, or irregularly resected and whether the middle vault is straight or deviated. In addi- tion, I palpate carefully to ascertain whether the dorsal septum at the anterior septal angle was underresected, contributing to a pollybeak deformity.

For the tip, I carefully examine and assess tip symme- try, projection, rotation, alar–columellar relationship, and lower lateral crural characteristics such as overresection and bossae formation. I palpate to assess tip support. I examine the caudal septum to see if it is straight or twisted. I examine all incisions, both endonasal and exter- nal. I examine carefully for the presence of possible grafts.

Functional Nasal Examination

Static and dynamic nasal valve collapse are commonly encountered in revision rhinoplasty patients. 11–16 In Becker et al.’s report, 19 of 21 patients with nasal valve collapse reported a history of rhinoplasty. 16

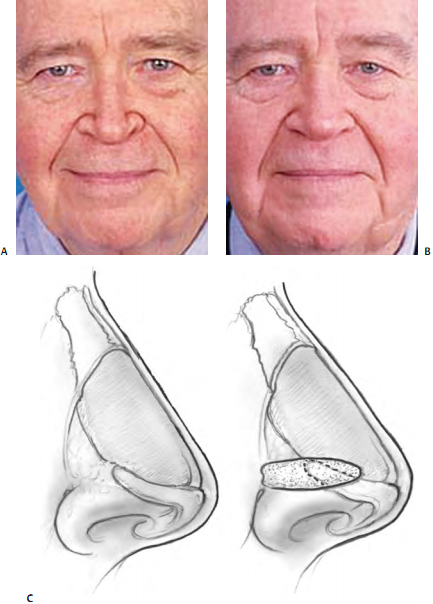

Pinching of the nasal sidewall and alar retraction are hallmarks of nasal valve collapse (Fig. 18–2). Observing the patient performing normal and deep nasal inspiration may lead directly to the diagnosis of nasal valve collapse. A “modified” Cottle maneuver, in which the lateral nasal sidewall is supported and elevated slightly with a ceru- men curette of similar device, is strongly supportive of the diagnosis when the maneuver results in the patient’s report of significant subjective improvement in nasal breathing.

Anterior rhinoscopy is undertaken and may help identify abnormalities such as deviated septum, inferior turbinate hypertrophy, synechiae or scar bands, septal perforation, and other abnormalities. Examination also includes nasal endoscopy when there is a complaint of nasal obstruction. 17,18 If indicated, a sinus computed tomography scan may also be obtained.

Pownell et al. described diagnostic nasal endoscopy in the plastic surgical literature. 17 They traced the historical development of nasal endoscopy, explained its rationale, reviewed anatomic and diagnostic issues including the differential diagnosis of nasal obstruction, and described the selection of equipment and correct application of technique, emphasizing the potential for advanced diag- nostic potential.

Levine18 reported that 39% of patients with a com- plaint of nasal obstruction had findings on endoscopic examination that were not identified with traditional rhinoscopy. Many of Levine’s patients had seen other physicians for this problem and had not received appro- priate treatment.

Table 18–1 Simplified Algorithm for Visual and Manual Nasal Examination in Revision Rhinoplasty*

| General Primary concerns Skin quality Problems Frontal Width Dorsum Middle Vault Tip Base Tip

Base Columella Lateral Nasal length Oblique | Identify primary concerns leading patient to seek revision rhinoplasty. Integrity, vascularity, mobility, skin thickness (thin, medium, or thick). For each issue and anatomic area, is problem because of underresection, overresection, asymmetric resectionNarrow, wide, normal, “wide–narrow–wide”? Twisted or straight (follow brow-tip aesthetic lines)? Open roof? Rocker deformity? Visible or palpable deformities? Prior osteotomies? If so, normal or abnormal? Assess width. Inverted V? Underresected? Overresected? Asymmetric? Deviated, bulbous, asymmetric, amorphous? Symmetry, bossae? Tip support (palpate)? Status of all prior incisions. Assess for presence of grafts. Alar sidewall pinching or retraction?Deviated, wide, bulbous, bifid, asymmetric? Symmetry, bossae? Status of caudal septum, projection, tip support (palpate). Status of all prior incisions. Assess for presence of grafts. Triangularity: good versus trapezoidal? Wide, narrow, or normal? Inspect for caudal septal deflection. Assess status of all external incisions. Columellar–lobule ratio (normal is 2:1 ratio). Status of medial crural footplates.Shallow or deep? High or low? Straight, concave, or convex: bony, bony-cartilaginous, or cartilaginous (i.e., is convexity primarily bony, cartilaginous, or both)? Visible or palpable irregularities? Overresected, underresected, or both? Pollybeak? Saddle nose? Normal, short, long? Projection (normal, increased, decreased)? Rotation (nasolabial angle), double break, alar–columellar relationship, Bossae? Status of caudal septum and tip support. Status of all prior incisions. Assess for presence of grafts. |

Does it add anything, or does it confirm the other views?

*There are many other points of analysis that can be made on each view, but these are some of the vital points of commentary.

Becker et al. described that, in patients seeking cos- metic nasal surgery who also had nasal obstruction, nasal endoscopy (Fig. 18–3) allowed the diagnosis of additional pathology not seen on anterior rhinoscopy, including obstructing adenoids, enlarged middle turbinates with concha bullosa, choanal stenosis, nasal polyps, and chronic sinusitis. 19,20 In their series, additional surgical therapy was undertaken in 28 of 96 rhinoplasty patients because of findings on endoscopic exam. Thirteen patients had endo- scopic sinus surgery. Nine patients had a concha bullosa requiring partial middle turbinectomy. Three patients—all revision surgeries—had persisting posterior septal devia- tion requiring endoscopic septoplasty. Two patients underwent adenoidectomy. One patient required repair of choanal stenosis.

Discussion with Patient of Surgery and Surgical Goals

If, after careful examination, the patient’s goals appear to be reasonable and realistic to this point, I will tell them so. I will let them know whether I feel this will be a routine or complex revision rhinoplasty in my hands. I explain tech- nical details of the surgical plan to the patient.

Next, we undertake computer imaging. The office com- puter network provides for imaging in each examination room. The patient’s photos are uploaded onto the com- puter screen in the examination room, and computer imaging is undertaken.

I explain to the patient that computer imaging is just a “video game,” that it is a way to communicate a shared sur- gical goal. I explain that of course this is not an “after” pic- ture, that it is not a guarantee and should not be taken to even offer the slightest implication of a guarantee. It is sim- ply a way to communicate the shared surgical goal. I do not provide the patient with printouts of the computer imaging.

I explain to the patient that I routinely print out the pre- operative photo and shared surgical goal photo and tape them to the wall in the operating room during surgery so that I can refer to the pictures as surgery progresses.

Typically, we are able to reach a shared surgical goal. If so, I then reiterate my impression that the goals are rea- sonable and realistic. We discuss technical details further. We review the potential benefits and potential risks of surgery. After we have concluded, I introduce them to my office manager for a discussion of logistical and financial details.

Patient Education

It has been my experience that, in general, the revision rhinoplasty patient has researched the subject exhaus- tively. These patients generally feel that they did not do enough research for their primary rhinoplasty. A signifi- cant number of revision rhinoplasty patients avail them- selves of the tremendous amount of educational material on the Internet. They are interested in learning about the procedure in general and are interested in preoperative and postoperative photographic images by their potential revision surgeon.

I believe that the best patient is a well-informed patient. In an effort to provide detailed information to those researching this subject, I created a Web site:www.RevisionRhinoplasty.com. In addition to the requi- site logistical information, considerable effort has been placed in providing a detailed educational tutorial at my Web site. Consequently, I have found that the patients I see in the office already know “what is wrong” with their nose and are already reasonably well-versed in my approach and philosophy.

Computer Imaging of Shared Surgical Goal

As stated previously, computer imaging is just a “video game.” It is simply a way to communicate a shared surgical goal. It does not generate an “after” picture. As I explain to patients, it is not a guarantee and should not be taken to offer even the slightest implication of a guarantee. I do not provide the patient with printouts of the computer imaging.

Having said this, I find computer imaging to be extremely useful. I routinely print out the preoperative photo and shared surgical goal photo and tape them to the wall in the operating room during surgery. I review my notes and these photos preoperatively and throughout surgery to keep the goal of surgery foremost in my mind as surgery progresses.

Special Challenges of Revision Rhinoplasty

The nationally reported revision rate for primary rhino- plasty ranges from 8 to 15%. 1–8 Sadly, there will likely never be a shortage of patients requiring revision rhinoplasty. Experienced revision surgeons consistently achieve a high level of satisfaction among their patients. Still, complica- tions can occur despite technically well-performed sur- gery. All surgeons have complications.

Revision surgery is different from primary surgery. Often the tissue planes have been obliterated, precious tissue has been overresected or asymmetrically resected, and healing forces have distorted weak or weakened cartilages.

The elasticity and quality of the skin–soft tissue enve- lope is a critical limiting factor in revision surgery and must be factored into the surgical plan. In addition, the revision surgeon must undertake a careful analysis of the existing cartilage and bony structure. This requires analy- sis of the existing structure and a mental reconstruction of the patient’s “normal” preoperative anatomy.

Specific Problems

Having the opportunity in my practice to examine a large number of revision rhinoplasty patients from across the country and around the world, I have observed a wide range of problems. A detailed listing of problems encoun- tered in the revision patient is found elsewhere in this text. Here, I have selected problems encountered in my revision practice that I feel warrant highlighting, either because they are problems that I encounter frequently or because they illustrate specific surgical techniques that may be particularly useful in your armamentarium, if they are not already there.

Overresection of Lateral Crura 6,20–23

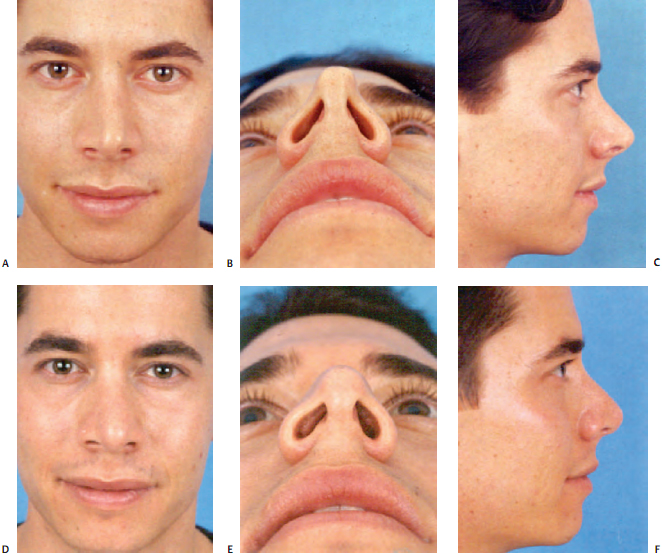

Overresection of the lateral crus is perhaps the most com- mon problem I see in my revision rhinoplasty practice. Overresection of the lateral crus leads to the predictable changes of alar retraction, pinching, bossae, and tip asymmetry (Fig. 18–4). Excision of vestibular mucosa in pri- mary rhinoplasty also may contribute to scar contracture with alar retraction.

It is important to note here that I have also found, in a significant number of revision cases, that the amount of lateral crus that remained appeared ample. It appears that in these cases, the scar contracture caused by healing overpowered the remnant cartilage. It has become clear to me that if the tip cartilages are soft and weak, and if the scar contracture is profound, undesirable changes can occur.

In some cases, this situation can be anticipated. In an anatomic study of the alar base, Becker et al. recognized that in a normal patient population, 20% of patients had a thin alar rim24. This anatomic variation must be recog- nized, and cephalic resection should probably be avoided in these patients to minimize the risk of alar retraction or external nasal valve collapse. 21 However, these changes are not always predictable and are not always avoidable.

Understanding that the healing forces are not com- pletely predictable, it is important to take a conservative approach when undertaking cephalic resection. Risk can- not be eliminated but can be reduced in this manner.

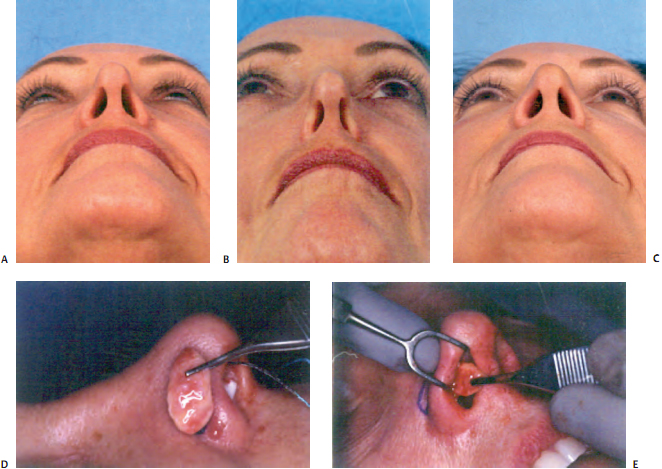

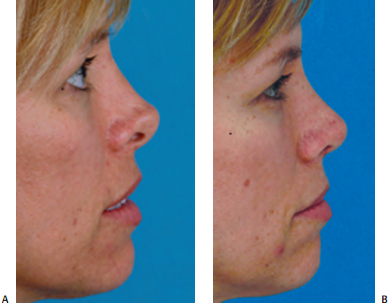

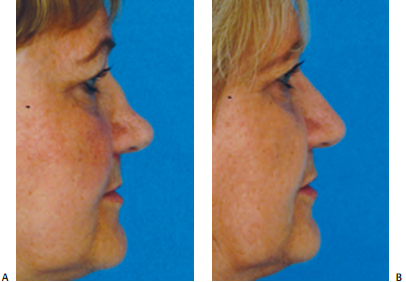

Alar batten grafts are the first line treatment of alar retraction and nasal valve collapse (Fig. 18–5). 10,11,16 Batten grafts have been very well described in the literature. Alar retraction may be treated by cartilage batten grafts in less severe cases (1–2 mm). 10 The area of retraction is marked before injection, and a small marginal incision allows dis- section of a precise pocket. (If an open approach is elected, a precise pocket may still be created for the batten graft, but suture fixation also may be required.) A contoured car- tilage graft (commonly of auricular or septal cartilage) may be inserted into the precise pocket, which should extend inferiorly to the sesamoids and should be wide enough to simulate the normal shape of the lateral crus at the dome.

Auricular composite grafts are commonly used in more severe cases (Fig. 18–6). 22,23 It has been my experience that the skin and cartilage of the anterolateral surface of the ear, just inferior to the inferior crus, of the opposite ear (example, left ala, right ear) provides the best donor site and the best contour. An incision several millimeters from the nostril rim is followed by careful dissection with free- ing of adhesions, creating a defect and displacing the alar rim inferiorly. Volume and support must be restored to hold the nostril rim in position; this role is fulfilled by the composite graft. The fashioned composite graft is carefully sutured into place. 22,23 Typically, I use 5–0 chromic suture. I place a cotton ball or other light dressing intranasally to apply light pressure for 1 to 3 days.

Composite grafts are easiest to place when undertaking a limited, precise pocket approach. When more extensive rhinoplasty is being performed, with wider elevation undertaken, the surgeon may be concerned that the com- posite graft will not stay in position. However, I have not found this to be the case. Composite grafts may be used in conjunction with alar batten grafts.

This fullness will typically decrease over 2 to 3 months. For maximal support, the alar batten graft should extend over the bone of the pyriform aperture.

Alar–Columellar Disproportion

An alar–columellar disproportion may be caused not only by alar retraction but also by a hanging columella or a combination of both (Fig. 18–7). 10,25 Retrodisplacement of the columella may effectively address the columellar con- tribution to the abnormality. Depending on the anatomy encountered, the medial crura may be retrodisplaced onto the caudal septum. Alternatively, excision of excessive caudal septum may be appropriate in selected cases. When redundant septal mucosa exists, excision and suture reapproximation also can be effective.

Nasal Dorsum Complications

Under Resection and Asymmetric Resection

When revising a nasal dorsum that has been underresected or asymmetrically resected, adherence to these princi- ples—sharp osteotomes and an anatomic approach—allows for the best chance for improvement in my hands. Sharp osteotomes are essential to provide for a clean, precise bony hump excision. When the osteotome is dull, the chance of an asymmetric resection or overresection of the bony hump increases. Some surgeons have at least two sets of osteotomes and rotate them so that one set is always out, being sharpened. Other surgeons sharpen their osteotomes manually with a sharpening stone during each case. Both approaches are effective.

An anatomic approach is preferable. Detailed anatomic nasal analysis should guide surgery. For example, when undertaking a hump reduction, the surgeon should exam- ine the excised tissue, assessing its symmetry, and whether it was the desired excision. (Of course, if the bony dorsum is rasped this will not be possible) (Fig. 18–8). Similar anatomic examination of the remaining cartilagi- nous and bony nasal dorsum also must be undertaken. It is expected that additional, calibrated refinement will be needed and should be undertaken with dogmatic adher- ence to the anatomic examination. Preoperative markings on the skin may be helpful to some surgeons for hump reduction, as well as for osteotomies.

In addition, persistent irregularities of the bony dorsum may be addressed by rasping. I find the powered rasp to be far preferable to manual rasping in this situation (Fig. 18–9). 26–28

Pollybeak

A pollybeak refers to a specific problem of the nasal dor- sum, specifically postoperative fullness of the supratip region, with an abnormal tip–supratip relationship. This may have several etiologies, including failure to maintain adequate tip support (postoperative loss of tip projection), inadequate cartilaginous hump (anterior septal angle) removal, or supratip dead space and scar formation.

Treatment of the pollybeak deformity depends on the anatomic cause. 29 If the cartilaginous hump was underre- sected, then the surgeon should resect additional dorsal septum. Adequate tip support must be ensured; maneu- vers such as placement of a columellar strut may be of benefit. If the bony hump was overresected, a graft toaugment the bony dorsum may be beneficial. If a polly- beak is from excessive scar formation, Kenalog (triamci- nolone) injection or skin taping in the early postoperative period should be undertaken before any consideration of surgical revision.

Overresection and Saddle Nose

Saddle nose refers to the appearance of the nose after loss of support of the nasal vault with subsequent collapse (Fig. 18–10). This deformity has been described after overresection of the septum with failure to preserve an adequate L-strut. A minimum of 15-mm of cartilage is rec- ommended as a rule of thumb: if a dorsal hump resection is also planned, this must be accounted for in planning adequate L-strut for nasal support. Other causes of saddle nose deformity include septal hematoma, septal abscess, and severe nasal trauma. Excessive dorsal hump resection also leads to saddle nose deformity.

Onlay grafting can effectively camouflage and correct mild and moderate saddle deformities (Fig. 18–10). Single or multiple layers of septal cartilage or auricular cartilage are commonly used effectively. 30,31 Severe saddle nose deformity may require major reconstruction with can- tilevered cartilage or bone grafts. 32,33

Precise pocket grafting can be effectively used when this is an isolated problem (Fig. 18–10). The pocket is dis- sected over the anterior septal angle via bilateral limited marginal incisions. Bilateral incisions are used to ensure symmetry of the pocket so that the graft will lie straight. Asymmetric dissection of the pocket can be a cause for graft shifting. When a patient has thin skin, AlloDerm (LifeCell, Branchburg, NJ) may be used to provide some additional cushion. Although it appears that this may provide some lasting benefit, the long-term fate of AlloDerm is unknown (Fig. 18–11).

Alloplasts

My experience with alloplasts has been to remove them because they cause pain or an unacceptable cosmetic result, they became infected, and they extrude into the nose and also through the skin. There is disagreement within the field of rhinoplasty regarding the use of alloplasts. It is my feel- ing that the nose fulfills few of the requirements for use of alloplastic materials. If the alloplasty extrudes through the skin, the skin–soft tissue envelope is permanently and irreparably damaged. I discourage the use of Alloplasts in both primary and revision rhinoplasty.

Inverted-V–Middle Vault Collapse

In this deformity, the caudal edge of the nasal bones is vis- ible in broad relief. Inadequate support of the upper lateral cartilages after dorsal hump removal can lead to inferome- dial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages and an inverted-V deformity. 34 Inadequate infracture of the nasal bones is another significant cause of inverted-V deformity. The anatomic cause of inverted-V deformity must be iden- tified and addressed. Osteotomies with infracture of the nasal bones, spreader grafts, or both may be required.

Twisted Nose: Newly or Persistently Twisted

Persisting deviation after rhinoplasty may occur at the upper third, middle third, or tip of the nose or may occur postoperatively in a previously straight nose. Preoperative anatomic diagnosis is a critical component of successful treatment. Persisting deviation of the nasal bones may occur because of greenstick fractures or other problems with osteotomies. 35,36 Inherent deviations in the cartilage of the middle nasal vault may prove especially challeng- ing. 36 In addition, hump removal may uncover asymme- tries that result in postoperative deviation where none existed previously. Tip asymmetry may be overlooked pre- operatively, or it may be caused by asymmetric excision of lateral crura, asymmetric placement of a columellar strut or placement of an overlong columellar strut, as well as other causes. Several surgical maneuvers are available to address the deviated nose35,36 and are addressed in this text (Murakami et al., Chapter 8).

Skin–Soft Tissue Envelope

In the unoperated nose, the skin–soft tissue envelope has well-defined tissue planes in which avascular dissection may be undertaken. Vascular supply and lymphatics are found superficial to the nasal musculature. 37,38 Dissection in the proper tissue planes (areolar tissue plane, i.e., sub- musculoaponeurotic) preserves nasal blood supply and minimizes postoperative edema. Operating in the more superficial planes not only leads to a bloody surgical field but also risks damage to the vascular supply with poten- tial damage to the skin. Once the skin–soft tissue envelope is damaged, it can never be fully restored. The damaged skin creates an aesthetically displeasing appearance. 37,38

In revision rhinoplasty, the normal tissue planes are no longer present. Therefore, there is an increased risk, com- pared with primary rhinoplasty, of damage to the skin–soft tissue envelope. Meticulous dissection is there- fore essential in this setting.

Summary

The dedicated revision surgeon continues to acquire throughout his or her career an increasingly detailed understanding of the anatomy and of the problems that occur and a growing tool chest of techniques to achieve improvement or correction. The revision surgeon must attend to the patient’s surgical need and to their emo- tional and psychological needs. In this chapter, I have out- lined my approach and discussed some selected technical problems and my solutions to them. Focusing on the two essential goals—making patients happy and making this their last nasal surgery—I find revision rhinoplasty to be a uniquely rewarding experience for both patient and sur- geon.

References

- Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders; 1997

- Kamer FM, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, ed. Head and Neck Surgery Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott; 1998: 2291–2302

- Rees TD, ed. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders; 1980

- McKinney P, Cook JQ. A critical evaluation of 200 rhinoplasties. Ann Plast Surg 1981;7:357–361

- Thomas JR, Tardy ME. Complications of rhinoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J 1986;65:19–34

- Tardy ME, Cheng EY, Jernstrom V. Misadventures in nasal tip sur- gery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20:797–823

- Simons RL, Gallo JF. Rhinoplasty complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;2:521–529

- Becker DG. Complications in rhinoplasty. Papel I, ed. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme; 2002; 452–460

- Goin JM, Goin MK. Changing the Body–Psychological Effects of Plastic Surgery. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1981

- Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 1999

- Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger MS, Tardy ME. Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:802–808

- Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:38–54

- Goode RL. Surgery of the incompetent nasal valve. Laryngoscope 1985;95:546–555

- Sheen JH. Spreader graft: A method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73:230–237

- Constantian MB. The incompetent external nasal valve: Pathophysiology and treatment in primary and secondary rhino- plasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;93:919–933

- Becker DG, Becker SS. Alar batten grafts for treatment of nasal valve collapse. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 2003;13:259–269

- Pownell PH, Minoli JJ, Rohrich RJ. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99:1451–1458

- Levine HL. The office diagnosis of nasal and sinus disorders using rigid nasal endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;102: 370–373

- Becker DG. Septoplasty and turbinate surgery. Aeasthetic Surg J 2003;23:393–403

- Lanfranchi PV, Steiger J, Sparano A, et al. Diagnostic and surgical endoscopy in functional septorhinoplasty. Facial Palst Surg 2004;20:207–215

- Becker DG, Weinberger MS, Greene BA, Tardy ME Jr. Clinical study of alar anatomy and surgery of the alar base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:789–795

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Alar retraction: Composite graft correction. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6:101–107

- Tardy ME, Genack SH, Murrell GL. Aesthetic correction of alar–col- umellar disproportion. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1995;3: 395–406

- Becker DG, Weinberger MS, Greene BA, Tardy ME Jr. Clinical study of alar anatomy and surgery of the alar base. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:789–795

- Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Friedman RM. Classification and correction of alar–columellar discrepancies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;97:643–648

- Becker DG, Park SS, Toriumi DM. Powered instrumentation for rhinoplasty and septoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32: 683–693

- Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME. Powered instrumen- tation for dorsal nasal reduction. Facial Plast Surg 1997;13: 291–297

- Becker DG. The powered rasp: advanced instrumentation for rhino- plasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2002;4: 267–268

- Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger RY, Key M. The cartilaginous polly- beak: Etiology, prevention, and treatment. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6: 113–120

- Tardy ME, Schwartz M, Parras G. Saddle nose deformity: Autogenous graft repair. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6:121–134

- Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Augmentation rhinoplasty: Dorsal onlay grafting using shaped autogenous septal cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;86:39–45

- Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty and rib grafts: Evolving a flexible operative technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;94:597–611

- Murakami CS, Cook TA, Guida RA. Nasal reconstruction with artic- ulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:327–330

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault. Operative Techniques in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1995; 2:16–30

- Larrabee WF Jr. Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:23–38

- Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative surgical management of the crooked nose. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:63–78

- Rettinger G, Zenkel M. Skin and soft tissue complications. Facial Plast Surg 1997;13:51–59

- Toriumi DM, Mueller RA, Grosch T, Bhattacharyya TK, Larrabee WF. Vascular anatomy of the nose and the external rhinoplasty approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996; 122:24–34