Abstract

The approach used by the founding fathers of rhinoplasty has incorrectly been called “closed” rhinoplasty. By implication, the term “closed” suggests that the surgeon cannot see or access vital areas of the nose during surgery. The term “endonasal” more accurately describes this particular approach. Until the 1980s, rhinoplasty was mainly thought of as surgical reduction of the nose.

With the advent of “open” or “external” septorhinoplasty in the late ‘70s, the former endonasal techniques were progressively abandoned, especially in North America.

By the end of the 20th Century a gradual appreciation of the problems associated with external rhinoplasty entered our common experience. It became apparent that the pendulum had swung too far in favour of the external approach.

A critical rethink of the past 100 years has become imperative. Neither the excesses of reduction endonasal rhinoplasty, nor the plethora of techniques in the external approach hold all the answers for our ever more demanding patients.

Hybrid Rhinoplasty seeks to amalgamate the best techniques from the competing worlds of endonasal versus external approach rhinoplasty in order to create a stable and cosmetically acceptable nose that matches the patient’s wish list for change.

Key words: rhinoplasty, external, endonasal, hybrid approach.

Introduction

Jacques Joseph (1865-1934) pioneered modern rhinoplasty in the early part of the 20th Century. His revolutionary approach to the difficult problems posed by rhinoplasty included using applied anatomy to surgical techniques, and appreciating the psychology of facial plastic surgeons. This revolutionary approach to rhinoplasty surgery found its way from Europe into the USA thanks to the efforts of Fomon, Aufricht, Kazanjan and others, who also promulgated the practice of surgery based on anatomical appreciation and research.

The approach used by these founding fathers of rhinoplasty has often, and incorrectly, been called “closed” rhinoplasty. The term “closed” is profoundly misguided as it implies a blind approach to nasal structures, and should be dropped from current nomenclature.

Endonasal rhinoplasty is a much more sensible term as it describes the surgical approach more accurately, and is not weighed down by implications of unseen structures, and guess work in the dark. The term “endonasal” will be used throughout this paper.

Until the 1980s, rhinoplasty surgery was mainly conceived and taught as reduction rhinoplasty, involving resection of the dorsal convexity, fairly aggressive management of the tip cartilages and shortening of the caudal lower third. The excessive removal of cartilages and support structures led to long-term problems and surgical stigmata. Despite its problems, the process of reducing the nose continued until the ‘70s and formed a backdrop for the next big leap forward.

The major change arrived in 1970 when a Yugoslav surgeon, Ivo F. Padovan presented his paper on external approach rhinoplasty to the inaugural meeting of the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS).2 Canadian, and later American surgeons soon realised the importance of his work and soon adopted Padovan’s technique.

Within a few short years, this revolutionary new approach, born in Europe, swept across the North American Continent, returned to Europe, and established itself as the backbone of rhinoplasty education in many centres around the World.

In essence, external approach rhinoplasty allows the surgeon to visualise, assess, and modify the structures of the nose under an “open sky” or “ciel ouvert” 3,4.

Advantages of this external approach include full visualisation of the operative field that allows the assistant or trainee surgeon to appreciate the surgical steps, the ability to create minute changes to the tip, and a rarely visible columellar incision line.5-7 The deconstructed nose is then reconstructed in order to regain its stability, usually with the aid of grafts held in place with sutures.

With the advent of external approach rhinoplasty, and its meteoric rise, the vast majority of rhinoplasty were trained in this particular approach. However, as no rhinoplasty technique is absolutely perfect for every scenario, a gradual appreciation of the problems associated with external rhinoplasty has entered our common experience.

Grafts hold centre stage in the external approach for good reason: once the nose has been deconstructed, it then must be reconstructed. This philosophy has led to the creation of an army of grafts, most of them not passing the test of time. Long-term appraisal has shown that grafts may move with time, and become visible through thin skin.8 The terminal demise of the shield graft – which was so popular only few years ago – is a timely reminder of the pitfalls of routine grafting.

In addition, one of the difficult problems frequently encountered by rhinoplasty surgeons is represented by revision rhinoplasty surgery in septal cartilage-depleted patients. In this special category of patients the septal cartilage had been removed for extensive grafting during the primary operation. Such a distinct lack of septal cartilage deprives the revision rhinoplasty surgeon from one his most important reconstructive tools, and obliging him to use various non-nasal tissues. Conchal cartilage and rib may be shaved and sutured into various shapes and sizes, but they neither look, nor feel the same as indigenous nasal cartilage. A nose must not only look good, but it must also feel like a natural nose, rather than a rigid structure. This semi-flexible nature of the tip cannot be replicated with conchal cartilage or rib.

Other potential problems with the external approach include a longer period of tip-oedema that many patients find undesirable as they wish to return to work as soon as possible, and the uncommon complaint of a visible columellar scar, which is not hardly amenable to correction.

Most primary rhinoplasty patients often complain about a large dorsal hump and an unsightly nasal tip. Neither of these 2 complaints really requires an external approach and can be dealt with adequately through an endonasal technique. For the majority of patients who do not seek large changes in their nose, an external approach can be excessive.

Clearly, we are at a stage where a sober rethink of the past 100 years has become imperative. Neither the excesses of reduction endonasal rhinoplasty, nor the plethora of grafting/suturing techniques in the external approach can manage to supply all the answers to our ever more demanding patients. A nose looks beautiful when its surface aesthetics comply with known criteria. In other words, it is not always necessary to restructure the depths to gain a beautiful surface. However, the experienced surgeon also appreciates that a surface blemish may reflect deeper problems that have to be addressed. Constant self-appraisal and attention to complications has led to the creation of a third way in rhinoplasty: a hybrid approach that seeks to combine the best elements of both worlds.9

Discussion

Pre-operative work-up

The tortuous process of rhinoplasty starts and ends with detailed attention to the history and the patient’s wish list for change. It forms the basis of a successful outcome. The techniques involved in patient communication can take many years to master and should initially be taught in medical school, and perfected in post-graduate years through continuous education. Whether using simple clinical questions or the latest edition of the SNOT questionnaire, the history forms the foundation for all other steps in rhinoplasty.

In aesthetic rhinoplasty, many patients present with rhinological symptoms in addition to cosmetic deformity. The rhinoplasty surgeon must be able to take a comprehensive ENT history, and perform nasendoscopy with efficiency and ease. Video-documentation of internal nasal pathology has now become routine in many rhinoplasty centres. Failure to treat nasal pathology in conjunction with aesthetic rhinoplasty will result in a disappointment result for patients, as their nasal symptoms will continue despite surgery. Indeed, sometimes rhinoplasty can exacerbate pre-existing symptoms and create a major loss of trust in the surgeon.

During the examination, particular attention should be paid to the quality and texture of the soft-tissue envelope as this layer has a significant impact on the final result and can lead to major changes in the pre-operative planning procedure. Very thick skin and subcutaneous layers can dampen the external result of Lower Lateral Cartilage (LLC) sculpting.

Tip palpation will also provide invaluable information about firmness, configuration and orientation of LLC. These structural features will dictate the operative strategy. Precise resections and domal sutures will work better in strong LLC whereas inherently weak, or damaged cartilages may require strengthening through various means.

Palpation of the nasal spine should also be carried out as it may elucidate one of the causes for an over-projected tip.

Facial photography should be carried out by the surgeon, and in a highly organised and systematic manner. The results of photography should be consistent in their colour quality, and light exposure. Excellent texts by well-known authors have already described the ideal settings for photography and a detailed description of these criteria is beyond the scope of this discussion.

Before the patient leaves the office for the first time, the surgeon should have already established a good rapport, performed a full ENT and nasendoscopy examination, taken photographs to a very high standard, and requested ancillary investigations based on the patient’s rhinological symptoms. No major decisions are ever made based on a single visit. Both the patient and the surgeon now require time to fully appreciate the consequences of their meeting and form a plan for further discussion and planning. Patients cannot be expected to understand every aspect of a detailed and often-difficult operation based on a single visit. For this reason, providing them with written literature, and possibly information on the Internet, gives them the chance to ruminate and cogitate the possible results of their decision to alter their appearance.

The clinical photographs now form the basis for facial analysis. The hybrid rhinoplasty (HR) surgeon must strike a reasonable balance between measuring the seemingly unlimited number of angles and facial contours, and not obtaining enough information for the decision making process. In other words, facial analysis for rhinoplasty must have clinically relevant applications that will have a bearing on operative planning.10 The frontal view provides basic information on facial proportions, and the subtle interplay of light and shadow on the nose. With the light shining from a central source, the midline of the nose should appear bright as it reflects the light back towards the camera. The borders with the lateral shadows signify the observed brow-dome lines (BDLs): a key landmark that is often skewed by an underlying crooked septum, and whose restoration forms one of the major tasks in re-establishing surface aesthetics. The brow-dome line starts at the medial head of the eyebrow, also called the mace’s head, turns inferiorly, and in parallel with its partner from the other side, heads towards the dome of the LLCs. These 2 BDLs should ideally also form the border of the light-shadow border. While the inferior aspect of the BDLs in females can end parallel to each other, it is not uncommon to notice a slight lateral divergence in males just before they reach the domes. The alar-columellar relationship, also dependent on the anatomy of the septum, has been compared the wings of a gull in flight. Its distortion can be a reflection of abnormal anatomy of the septum, LLC, columella, soft-tissue envelope, or any combination of these factors.

The lateral photograph is a vital view as it provides information of key landmarks that have to be reformed. These include: the radix, nasion, maximal dorsal height, supratip area, pronasale, and the effect of the depressor nasi septi muscle on the upper lip and tip position in the dynamic phase. There are several well-known formulae for the calculation of ideal rotation and projection; however, they must be analysed in the framework for the particular nose under review. Facial analysis is not simply a mathematical formula applied by an architect to a building: the face and nose are mobile structures whose dimensions need to be considered as part of a dynamic, harmonious whole.

The base-radix, base, and helicopter views form a triad designed to show the major abnormalities of the tip, the alar-columellar relationship, alar flare, alar width, and bony bridge width. In contemporary practice, the HR surgeon must be familiar with the range of racial features, as the variety of nasal tips, and ala, is truly staggering. One formula does not fit all cases.

The results of facial analysis create a list of nasal features that are amenable to change and sometimes also suggest supplementary alterations to neighbouring structures that could assist in obtaining the desired results. A good example of such an extra procedure is chin implantation for retrognathia. These results and plans are conveyed to the patient during the second consultation. The surgeon then reconsiders the patient’s wish list and compares it to the results of facial

online cialis sales

analysis. A tailor-made operation based on these desires for change and physical finds is then created for the patient. Each rhinoplasty becomes a unique operation that reflects sober reflection, calculation, and discussion and must not be repeated for another patient. Simply repeating the same operation for every patient is no longer acceptable in current practice and must be strongly discouraged.

Techniques of Hybrid Rhinoplasty

As a surgeon practicing in the 21st Century, re-assessing dogma passed down by generations of teachers, flexibility in thinking processes, and self-assessment form the foundations of progressive rhinoplasty. As junior surgeons learn their skills, they inevitably emulate their masters, and pass through a learning curve that leaves them feeling comfortable with a particular style of surgery. Relearning the difficult techniques of rhinoplasty requires time and energy. However, if we are to make progress, the axioms of surgery must be re-visited in the light of current experience and scientific progress. At present, most rhinoplasty surgeons in North America use the external approach almost exclusively and would find a change in their practice difficult and time consuming.

In good hands, external approach rhinoplasty can achieve excellent results.11-14

Nevertheless, it is far from perfect. Mentioning all the problems of this approach is both misleading and counter-productive. The general consensus amongst rhinoplasty surgeons points to greater tip oedema, longer recovery time, a plethora of grafting techniques, and a small risk of a visible scar as some of the negative aspects of external rhinoplasty.15 Conversely, a purely endonasal approach that only reduces support structures and leads to long-term adverse effects is equally undesirable. These problems associated with dogmatic surgery, have set the background for a new, more balanced approach in the form of hybrid rhinoplasty (HR).

HR is not simply a reduction rhinoplasty under a new guise. Similarly, it does not negate the achievements of the external rhinoplasty. A dialectical approach to the problems posed by rhinoplasty leads us towards flexibility in our technical choices that are tailor-made for the reconstruction of surface aesthetics, and obtaining what the patient has specifically asked us to achieve. Although HR deals with surface aesthetics, its range of techniques allow the surgeon to undertake major structural changes or create subtle effects when necessary.

The game plan and patient’s photo-analysis results are displayed within eyesight of the surgeon and the assistant for constant monitoring. The CT scans of paranasal sinuses must also be displayed for patients undergoing simultaneous Endoscopic Sinus Surgery and HR. Every step of the operation is pre-determined, and followed meticulously. A major rethink in the middle of the operation points to poor facial analysis, and planning and should alert the surgeon toward greater self-appraisal.

Incisions & Approaches

The issue of the initial incision if of vital importance in HR, and requires detailed attention.16 As HR begins with an endonasal approach, the surgeon avoids the remote possibility of a visible or undesirable scar. Access to the septum and dorsum can be gained through a variety of hemitransfixion, transfixion, intercartilagenous, intracartilagenous, and infracartilagenous incisions.

At the beginning of the operation, a small volume of local anaesthetic with adrenaline is injected along the osteotomy lines, infraorbital nerve, and hemitransfixion incision. The volume has to be kept low, as distortions of surface anatomy are particularly unhelpful in the final stages of surgery.

The intracartilagenous incision not only provides direct access to the desired point of access, but also for sculpting the scrolls as required. In about 60% of cases, grafts and sutures can also be used in combination with the transcartilagenous approach. This may coupled with “slot” marginal incisions to access and modify the domes. Such an “extended” transcartilagenous approach, also allows for greater flexibility in dealing with complex tip problems and the recreation of surface aesthetics.

Overall, about 20% of cases require a standard delivery approach, 15% are carried out through an infracartilagenous incision, and 5% need a hemitransfixion incision for problems located in the midline, such as a saddle nose (PP personal figures).

It must be emphasised that the approach on one side may be completely different from the other, as noses are usually asymmetric. Performing the same operation on both sides in such cases reflects poor pre-operative facial analysis. For example, one side may require an intercartilagenous approach laterally that becomes intracartilagenous medially, while the other needs a marginal incision.

Short incisions designed to reconstruct important surface landmarks are of great practical value in HR. Also known as “slot” incisions, they are frequently used in combination with the transcartilaginous approach, inferior to the lower lateral cartilage (LLC) to recreate a natural looking ala through contour grafting, rim grafting, or the placement of lateral crura shaping sutures. Columellar slot incisions provide access for plumping, infra-tip grafts and columelloplasty.

Septal Surgery

Septal surgery is fundamentally important for the final result, and can be the most demanding part of the operation, especially in revision cases.17 As the shape and size of the septum has a significant effect on surface aesthetics, particular attention has to be paid to its anatomy.18 The dorsum and caudal aspects of the septum form an extremely important area that must be treated with utmost respect. Any aggressive removal of cartilage in these 2 areas that roughly form an “L” shape leads to disastrous long-term results if not restored. The anatomy of the caudal septum also forms the basis of safe septoplasty. Particular attention must be paid to the 3 angles that are all amenable to surgical modification. The anterior angle is particular important as some female patients desire to have a small supratip dip in this region. A very conservative removal of cartilage in this region is justifiable for this purpose. The intermediate angle is often neglected in rhinoplasty. Its removal results in a straight columella, and a very odd appearance on lateral views. This artificial appearance does not usually occur developmentally, and its presence points to one of the worst types of rhinoplasty stigma: an iatrogenic, and ugly columella. If the septum needs to be trimmed back, as in a tension nose, the intermediate angle must be recreated to prevent this complication. This can be achieved by using gently crushed cartilages and placed in-situ through precisely placed pockets accessed through a small slot incision just posterior to the columella.

The posterior angle forms a very important joint with the spine and deserves special mention. Along with the “key-stone” area, it forms the second fulcrum of stability and should be treated with equal care. When harvesting cartilage from the septum, the source should be limited to an area posterior to the spine-posterior angle junction. In a tension nose, a larger amount of cartilage may be removed as a single piece that extends from the floor of the nose to the spine, intermediate and anterior angles. Operating on these areas can deproject the nose: an effect that might be desirable, but which must be carried out with careful planning. A posterior chondrotomy is an incision that starts inferiorly at the cartilaginous-bony septal junction, and can be extended superiorly towards the “key-stone” area, but never reaching it. The amount of deprojection gained is proportional to the length of the posterior chondrotomy: the longer the incision, the greater the deprojection gained in the long term. Surgery on the spine must also be considered in this regard. Pre-operative palpation of the nasal spine will give the surgeon some idea about the length and symmetry of this structure. When excessively long, the spine can project the cartilaginous pyramid forward. It can be reduced in a number of ways. The aim should be to create a spine that is proportional to the amount of projection desired, and one that is symmetrical and capable of supporting the posterior angle. Asymmetry of the spine’s wings is not uncommon and must be addressed. Reduction and de-projection of the septum will not only reduce the amount of cartilage beneath the dorsum, but also have an important effect on the overlying LLCs whose asymmetrical appearance can sometimes be attributed to septal malformation, rather than inherent deformity. By creating space inferiorly and posteriorly, the septum can be de-projected without resorting to major cartilage excision.

As septal cartilage is often the most useful material for grafting, the judicious HR surgeon will preserve as much of the septum and replace the septal cartilage that has been removed during surgery. It will be then possible to harvest septal cartilage for a possible revision on that particular patients.

Tip surgery

HR of the tip is based on recreating surface aesthetics along with cartilage preservation. By preserving cartilage, the worst effects of reduction rhinoplasty are averted. Over the past 20 years two major practices in tip surgery have risen in popularity, and since diminished in their widespread acceptance. Placing multiple grafts in the tip is fraught with problems: the source for grafting in many noses should be the septum; however, in revision cases, the septum is often missing. Conchal cartilage and rib neither look, feel, nor behave like the LLCs. Rib grafts in particular can lead to a rigid tip, which is normally a semi-flexible structure. Other problems with tip grafting, specially shield grafts, include their visibility with thinner soft-tissue envelopes, and displacement with time. A nose looks beautiful when its surface lines and curves comply with aesthetic criteria. This can be achieved by placing gently crushed cartilage in precise pockets rather than resorting to large grafts. A certain amount of experience is necessary in deciding exactly how much crushed cartilage to use, and how to create precise pockets, but this technique circumvents the most glaring problems associated with older graft techniques. Suturing the LLCs also came into vogue, had its heyday, and is currently undergoing a slow demise, as the results are sometimes disappointing. Pulling the LLCs into various shapes with sutures can lead to iatrogenic stigmata, and have undesirable features such as sharp angles, “uni-tip”, tip asymmetry and alar notching. Increasingly, patients are demanding a natural, non-operated look. Although suturing techniques have the power to produce major changes in the shape and orientation of the LLC, they can also be too powerful in their effects and create a stereotypically “operated” looking nose. Despite some setbacks, sutures are frequently used to good effect. Examples of useful suturing techniques in HR include the transdomal and domes-binding sutures, septo-columellar sutures (“wonderbra” and “anti-wonderbra” sutures to control tip rotation), basicolumellar, tongue-in-groove, and subdomal sutures, each providing unique opportunities for tip modelling/repositioning without harsh effects.

Other techniques that have significant effects on surface aesthetics include reduction of the scroll area, and tip SMAS thinning. An intercartilagenous incision placed laterally and drawn medially to become an intracartilagenous incision provides direct access to the scroll area that can be reduced to give the distance between the lower border of the ULCs and the upper border of the LLCs a more sculpted appearance. Reducing the SMAS should only be attempted by the highly experienced surgeon and remain conservative in its extent. Access can be gained though a marginal incision, an instead of following a supra-perichondrial plane, the surgeon dissects the lower layers of tip-SMAS from the underlying cartilage and removes limited but precise amounts of fibro-fatty soft tissue under direct visual control.

Mid-nose surgery

Whenever possible, maintaining the integrity of the septo-lateral cartilage forms one of the fundamental axioms of HR.

The treatment of a high vault in a tension nose has often been approached by the dogmatic and routine splitting of the ULCs from their parent septum. Once the junction of the ULC and the septum has been cut, the standard teaching has been that it then needs to be immediately reconstructed with cartilage. This new triple layer sandwich (ULC-graft-septum) is then held together with sutures. The evidence for spreader grafts restoring nasal airflow is not set in stone, and the addition of cartilage in this area can broaden the middle nasal vault: a rare request on behalf of primary aesthetic rhinoplasty patients.

In HR, the vital area of the internal valve is not disturbed. Sometimes in humpectomy, the junction of the ULC and the septum is excised, however, this is not a routine step and is best avoided in order to keep the angle of the internal valve intact. A few decades ago, Robin, a French surgeon, introduced the idea of creating submucosal tunnels in the region of the ULC-septum junction and called it the “extra mucosal approach”. In HR, this technique is implemented bilaterally if necessary. The current thinking on this issue is that these redundant folds of mucosa between the transected medial end of the ULC and the septum create a spreader effect.18 The very rare occurrence of a pinched cartilaginous vault and inverted-V appearance as long-term complications may be interpreted as an objective evidence for this clinical impression. The vast majority of our patients, and women in particular, do not want to have a broader nose, so the routine interposition of a cartilage spreader graft is not justified.

The problem of reconstructing the mid-vault after humpectomy poses important issues that require further study and development. In most patients seeking cosmetic rhinoplasty, the undesirable appearance of a dorsal hump constitutes one of their main complaints. Although a hump has both cartilaginous and bony components, the cartilaginous portion tends to dominate the situation. Humpectomy involves excision of the midvault dorsum and may at time also necessitate reduction of the medial aspect of the upper lateral cartilages (ULCs). This creates 2 problems: damage to the internal valve (the angle between the ULC and its parent septum) and an open roof. Both of these iatrogenic problems can be addressed through HR techniques. First, if possible, the ULCs are not routinely cut away from their septum. This not only preserves the vital 15-degree angle of the internal valve, but also precludes the need for reconstruction. More recent techniques for reconstructing the internal valve include using the cut medial end of the ULC as an autospreader graft. This medial end is curled towards the midline and sutured to the septum. Scientific evidence promoting this technique is sparse, but some patients have reported improved NOSE scores. Alternatively, the HR surgeon may decide to dissect the perichondrium at the superior section of the septum and the internal valve and use it as a sleeve between the cut end of the ULC and the septum to create a spreader effect.19,20

Currently, the issue of the orientation of the LLC is occupying the minds of many rhinoplasty surgeons. A line drawn along the axis of the LLC should ideally point to the lateral canthus. Such an “orthotopic” LLC gives the nose an aesthetically pleasing appearance. However, the cephalic portion and medial aspect of the LLC may dominate the situation. This creates the impression that the LLC is pointing towards the medial canthus instead. In severe cases, this gives the nose the appearance of a “parenthesis deformity.” In such patients, the LLC is lacking along its inferior margin. Therefore, both the excess cartilage along the supero-medial border and the lack of cartilage alongside the inferior margin of the LLC need to be addressed.

In HR, the surface markings of the LLCs are marked on the patient’s face pre-operatively with detailed attention to the areas that need to be reduced, added, or modified as dictated by the results of facial analysis photography. First, an intracartilagenous incision gives access to the excessively large cephalic margin of the LLC. The undesirable portion of the cephalic aspect of the LLC is removed. This access also enables the surgeon to reduce the scroll area if necessary at the same time. The second step involves creating a marginal incision that starts medial to the superior and medial rotation pivot of the LLC. This incision then continues along a line where the actual margin of the LLC should be, rather than its real margin. In order to fill in the paucity of cartilage along the inferior border, a LLC extension graft is fashioned from a piece of sturdy septal cartilage and placed in a pocket that has been fashioned with the nasal skin above, and the vestibular skin below. Suturing the bevelled medial aspect of this graft to the lateral aspect of the paradomal segment of the LLC ensures that it will not move with time. Further stability is added by closing the pocket with 2 percutaneous sutures that pass through the graft and are loosely tied. This technique is in direct contrast to the external approach, which requires complete exposure of the LLCs, dissecting the vestibular skin, and sliding the lateral aspect of the cartilages into a pocket in the region of the pyriform aperture. This not only disturbs the complex fibrocartilaginous structure near the pyriform fossa, also known as the “hinge area,” but can also destabilise the LLC.

Osteotomies

The preoperative game plan of HR, tailor-made for the patient, will have detailed plans on the type and number of osteotomies. Correct assistance in supplying the hammer blows are very important and require mention. The mallet should hit the osteotome at 90 degrees in order to ensure a level cutting plane. If the strikes are at angles that vary from the perpendicular, the tip of the osteotome will not progress in a level plane and veer off course. The first blow of the mallet should be gentler and allow the tip of the freshly sharpened instrument to engage the bone. The second and more forceful blow will then glide the tip along a pre-determined path. All osteotomies and chisels must be sharpened for each operation as blunt instruments shatter bone rather than cut through it.

As the vast majority of noses in rhinoplasty are asymmetric, osteotomies should reflect this finding. Asymmetrically placed osteotomies seek to redress the balance of unequal lateral nasal walls and at times may require several on each side. Intermediate osteotomies, whether single or double are particularly useful in treating twisted noses. At times, a single osteotomy alone may be sufficient to achieve the desired result. Conversely, in severely twisted noses, the experienced HR surgeon ma may have to perform multiple osteotomies on both sides.

Grafting procedures

The use of grafts to re-stabilise the nose after an external approach rhinoplasty has had a great influence on the practice of rhinoplasty over the past 30 years. The external approach proceeds through destabilisation of the nose, before it can be restructured into the desired shape with the use of grafts. The use of grafts has evolved over the past 30 years. While grafts are not a panacea, their judicious use in HR provides a bridge between the often-competing worlds of endonasal and external rhinoplasty. The basic difference in HR grafting lies in the purpose of the graft itself. In HR, grafts are not used to regain the structural integrity of the nose, as this has not been breached or damaged in the first place. Rather, HR grafts are employed to help recreate surface aesthetic lines, soften contours, and create the “not-operated,” naturally beautiful nose that is the aim of rhinoplasty.

Allograft and alloplastic materials are not used in HR. Instead, preference is given to the most useful material for graft harvesting: the septal cartilage. For this reason, all septoplasty should include a serious attempt by the rhinoplasty surgeon to conserve as much cartilage as possible. While the removal of small amounts of septal cartilage is often necessary, due attention must also be paid to the role of the spine and the maxillary crest in providing room for maneuverability. Many patients have had a less than desirable rhinoplasty in Saint Elsewhere Hospital, and want to regain their natural look or simply repair the damage that has been done. In these cases, the lack of adequate septal cartilage as graft material may force the HR surgeon to obtain conchal or rib cartilage: these materials are greatly inferior to the septum as their mechanical properties are different to the septal dorsum, and the LLC. The best material for grafting nasal cartilage is the septal cartilage itself.

Septal cartilage may be used for structural reconstruction of the septum, as an onlay graft for dorsal defects, columellar struts, or batten grafts; alternatively, it may also be utilized for contouring surfaces. Common HR grafts include: dome and vault onlay, rim and radix, batten, and strut grafts.

Final touch-ups

By the end of the operation, the septum, tip, and osteotomies have been dealt with in detail, and always in keeping with the desired result. Nevertheless, final touches are at times necessary. A final checklist should include revisiting the game plan, and reviewing the most important aspect of rhinoplasty such as the new brow-dome lines, tip position, columellar configuration, osteotomies, and lateral profile. Small deficiencies can be filled with gently crushed cartilage. By the end of the operation, the nose is a structurally sound structure that will not deteriorate over time due to poor supports. The new nose complies with the patient’s wishes, and has a new set of surface aesthetics that reflect the results of facial analysis.

Alar base surgery

Increasingly, our patients are demanding scar-free rhinoplasty. This may be impossible to achieve specially when external incisions are created and closed without due attention to detail, or the patient’s skin type results in a dark line. The excellent Adamson’s algorithm21 delineates a logical and pragmatic approach to this problem. An uncomplicated, and some would claim simplistic way of analysing the ideal alar width includes drawing a tangent from the ala superiorly. Under “ideal” circumstances, both alae should be within a line drawn tangentially to the medial canthus. However, this “ideal” measurement refers to North West European faces, and cannot be applied to increasingly complex racial features around the world. For example, the vast majority of senior surgeon’s (PP) patient’s ideal alar flare is situated between vertical inter-caruncular lines rather then medial intercanthal lines.

So, the HR surgeon should consider the patient’s ethnic background before deciding on how much external reduction is possible or desirable. As with the external approach, the remote possibility of a scar must be avoided. In HR, the excessive alar width is not treated surgically in most of the cases. Instead, the patient is encouraged to consider alternatives such as the injection of hyaluronic acid immediately lateral to the ala. This produces medial displacement of the ala and can result in a modest reduction in the alar-columellar width. Another advantage of this relatively cheap technique is to allow the patient time to fully consider the possible permanency of a scar with an external incision approach. Changing the orientation and size of the nostril can be achieved by internal excisions in the vestibule: these do not leave external scars, and are appropriate when the alar-columellar width is not wide, and only the nostril orientation or size have to be altered. As such, they are in keeping with the scar-free ethos of HR.

Training and Education

Learning the long list of technical abilities involved in contemporary rhinoplasty can take years to master, and should not be taken lightly. Before the novice surgeon can attempt a difficult manoeuvre in HR, such as an intercartilagenous incision that becomes intracartilagenous more medially, or correctly placed “slot” vestibular incisions, he or she must gain mastery over the fundamentals of rhinoplasty. Usually, this means a pathway that starts with proficiency with the external approach, and later evolves, over a considerable period of time, into endonasal, and finally HR. Any attempt to skip vital steps in this long process of training and education may result in serious problems for the patient and the surgeon.

Conclusion

We stand poised over a new era in rhinoplasty. Patient’s demands have become increasingly more detailed and exacting. Clearly, a dogmatic approach to rhinoplasty cannot form the basis of a progressive surgical practice that must reflect contemporary scientific research and practice. Techniques used in Hybrid Rhinoplasty can tackle the entire rainbow of problems from subtle tip changes to major reconstruction, and create a nose that functions well, and looks natural and beautiful.

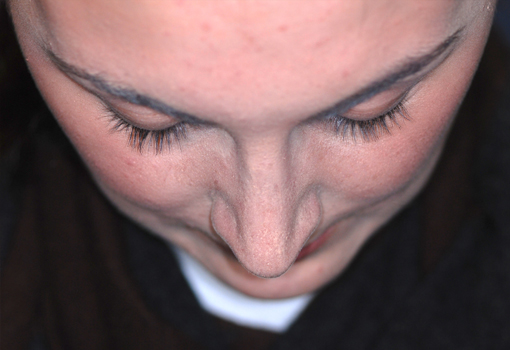

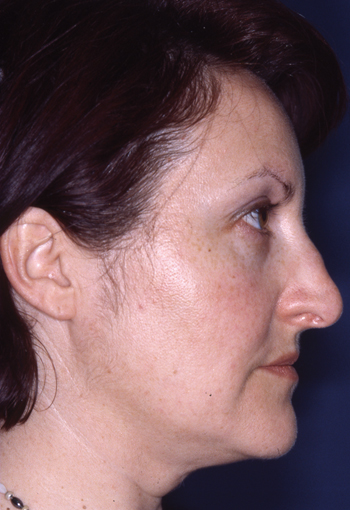

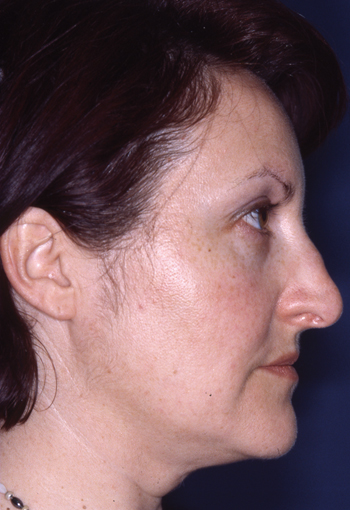

Legends for Case # 1

Pre-operative views.

Young female patient complaining about nasal hump as the main aesthetic concern.

Operation summary

1. Endoscopic septoplasty and septal cartilage harvesting 2. Intercartilaginous approach, assymmetric retrograde trimming of cephalic lower lateral cartilages 3. Humpectomy through “extramucosal” approach 4. Onlay cartilaginous graft over left dome through left vestibular “stab” incision 5. Bilateral rim grafts 6. High-low-high basal osteotomies and infracture 7. Contouring of the infratip through composite excision of vestivular/skin and septal cartilage 8. Tongue-in-groove suture.

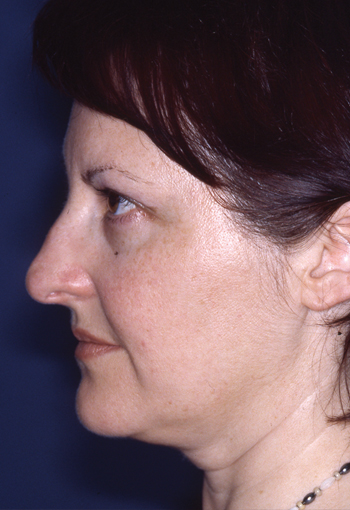

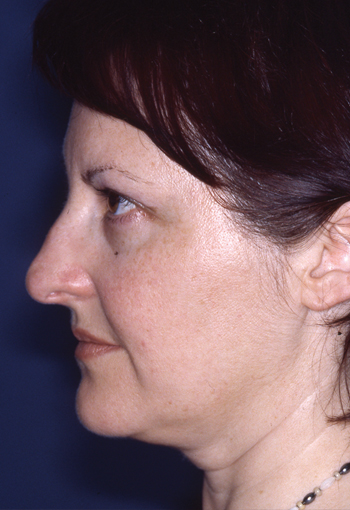

Post-operative views.

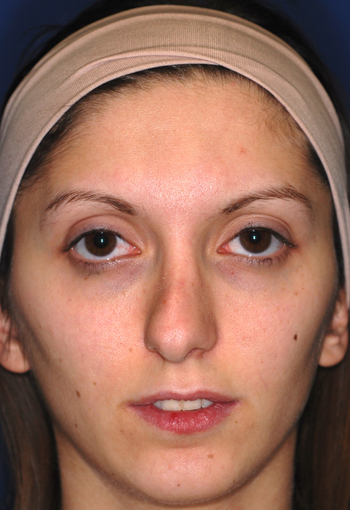

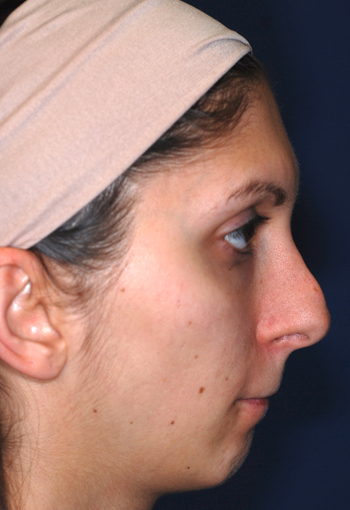

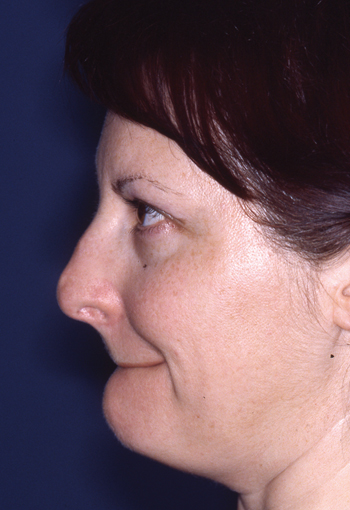

Legends for Case # 2

Post-rhinoplasty deformity.

Pre-operative views.

Pre-operative views of a young adult female revision rhinoplasty patient with polly tip, twisted tip, ACR (Alar Columellar Relationship) assymetry, lateral crura assymetry, poorly defined nasion.

Operation summary

1. Septoplasty – Perpendicular plate osteotomy – Harvest cartilage 2. Narrowing of the base of the columella – creation of intracolumellar pocket 3. Endonasal delivery approach. 4. Assymmetric (> on the right) excision of the cephalic borders 5. Excision of the cartilaginous polly tip 6. Rasping of the bony dorsum – Smoothening of the bony rails 7. Osteotomies (basal – straight paramedian – backfracture) 8. Domes-defining sutures 9. Wedge-sheped shortening of the caudal septal vestibular skin 10. Suture-fixation of the caudal septum inside the columellar pocket 11. Tongue-in-groove suture 12. Subdomal suture 13. Pedestal narrowing suture.

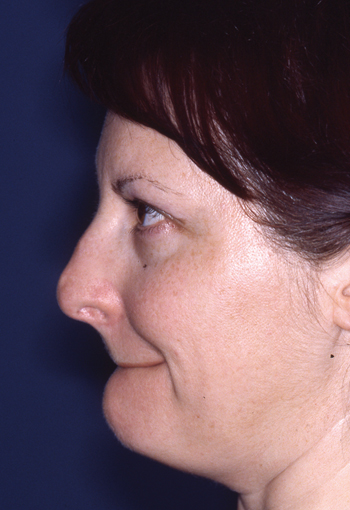

Post-operative views.

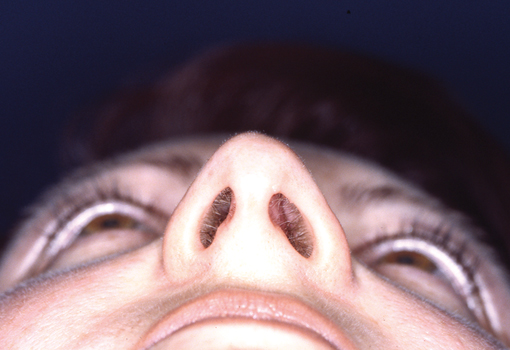

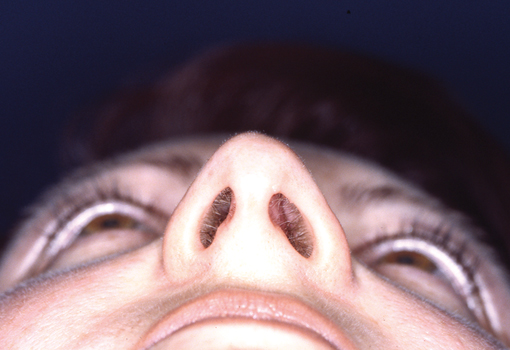

Legends for Case # 3

Post-rhinoplasty deformity.

Pre-operative views.

Pre-operative views of an adult female revision rhinoplasty patient with a twisted nose, wide and amorphous middle third, hanging columella, alar-cheek junction asymmetry, high and irregular profile line.

Operation summary

1. Septoplasty and septal cartilage harvesting, caudal septum shortening, 2. Columelloplasty 3. Assymmetric cephalic excisions of lower lateral cartilages & scrolls excision 4. Shaving of the bony-cartilagenous hump 5. Shaving of the left cartilagenous vault 6. Left bony vault rasping 7. High-low-high cialis basal osteotomies & infracture 8. Intermediate osteotomies 8. Dorsal onlay “contour” grafts 9. Septo-columellar “Wonderbra” suture.

Post-operative views.

References

- Gilman SL. Making the body beautiful: A cultural history of aesthetic surgery. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1999:17-193.

- American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, ed. Proceedings of the First International Symposium of the AAFPRS. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton, 1972.

- Baarsma EA External septorhinoplasty. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Volume 224, Numbers 3-4 / September, 1979:169-176.

- Pastorek NJ, Bustillo A, Murphy MR, Becker DG. The extended columellar strut–tip graft. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005; 7(3):176-184. FREE FULL TEXT.

- Simons R L, MD Perspectives on the evolution of rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2009; 11(6):409-411.

- Goodman WS. External approach to rhinoplasty. Can J Otolaryngol 1973; 2:207-210.

- Anderson JR, Ries WR. Emphasizing the external approach. New York. Thieme Inc.;1986

Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Nov;100(6):1547-52. - Collawn SS, Fix RJ, Moore JR, Vasconez LO. Nasal cartilage grafts: more than a decade of experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010 Dec 15;12(6):412-4.

- Palma P, Khodaei I. Hybrid rhinoplasty. The 21st century approach to remodeling the nose. Facial Plast Surg. 2011 Apr;27(2):146-59. Epub 2011 Mar 14.

- Palma P, Khodaei I, Tasman AJ. A guide to the assessment and analysis of the rhinoplasty patient. Facial Plast Surg. 2011 Apr;27(2):146-59. Epub 2011 Mar 14.

- Gunter JP. The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 99(3):863-867.

- Smith O, Goodman W. Open rhinoplasty: its past and future. J Otolaryngol 1993; 22(1):21-25.

- Aiach G. Atlas of Rhinoplasty: Open and endonasal approaches. 2nd ed. Quality Medical Publishing Inc, St. Louis, MO; 2003.

- Vuyk HD, Olde Kalter P. Open septorhinoplasty: experiences in 200 patients. Rhinology 1993; 31(4):175-182.

- Adamson PA, Smith O, Tropper GJ. Incision and scar analysis in open (external) rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990; 116:671-675.

- Tasman AJ, Palma P. The infracartilaginous approach revisited. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2008; 10(6):370-375.

- Kamer FM, McQuown SA. Revision rhinoplasty. Analysis and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1988; 114(3):257-266.

- Cirillo DP. Maxilla-premaxilla approach to septal surgery in the cosmetic patient. Ann Plast Surg 1988; 21(1):49-54.

- Cakir B, Oreroglu AR, Dogan T, Akan M. A complete subperichondrial dissection technique for rhinoplasty with management of the nasal ligaments. Aesthet Surg J 2012; 32(5):564-74

- Most SP, Analysis of outcomes after functional rhinoplasty using a disease-specific quality-of-life instrument. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2006; 8(5): 306-309.

- Warner JP, Chauhan N, Adamson PA. Alar soft-tissue techniques in rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010; 12(3):149-158