Abstract

Endonasal rhinoplasty has long been considered a reductive operation. With the advent of cartilage grafting and support and better understanding of nasal dynamics, endonasal rhinoplasty can be performed in a predictable manner. The advantages of shorter operative time, less prolonged postoperative swelling, and less postoperative skin contracture have allowed endonasal rhinoplasty to continue to serve a prominent role in addressing nasal deformities.

Introduction

Rhinoplasty describes an array of operative techniques that can be used to alter the aesthetic and functional properties of the nose. The experienced rhinoplasty surgeon can use either an endonasal or an external rhinoplasty approach, based on the patient’s rhinoplasty indications. Open rhinoplasty approaches have gained tremendous favor because of the ease of ability to completely and clearly diagnose structural problems via direct visualization, improved teaching capability and ease of use.

With endonasal rhinoplasty, there is generally not the same degree of disruption of soft-tissue support as is seen in open techniques. Although visualization is inferior as compared with these latter techniques, one can achieve tremendous beneficial changes in appearance with improvement of the airway by applying and maintaining a strict adherence to certain principles. The advantages of the endonasal approach include decreased operative times, rapid recovery, reduced postoperative edema, less significant scar contracture and a quicker return to a normal appearance. Profile adjustments are typically easier to judge in an endonasal approach because of having the soft tissue envelope remain undisturbed. Endonasal rhinoplasty will generally result in a more expeditious postoperative recovery if executed properly in selected patients. Generally, patient with severe nasal tip deformities with prominent asymmetries will be better served with open techniques. All other patients will do well with either approach.

Indications for closed rhinoplasty include (1) aesthetic deformity, (2) patient request for a change in nasal shape, and (3) improvement of anatomic nasal airway obstruction. As a great majority of rhinoplasties performed are elective in nature, the surgeon must select patients by surgical principles, the patient’s psychologic state, and the ethical consideration of minimizing any iatrogenic harm to otherwise healthy patients. Unstable mental status, unrealistic patient expectations, previous rhinoplasty within the last 9 months, poor perioperative risk profile, history of too many previous rhinoplasties and nasal cocaine users are common contraindications for this procedure.

The end product of a well-executed rhinoplasty includes (1) bilateral symmetry, (2) an unbroken brow-tip aesthetic line, (3) a straight nasal contour on frontal view, (4) adequate nasal sidewall shadowing, (5) a smooth dorsal profile, and (6) a nose that is in harmony with the rest of the face.

Preoperative Details

The key point in a successful rhinoplasty is the careful preoperative analysis of the patient’s concerns and nasal deformities. Accurate diagnosis of aesthetic and functional problems can then facilitate appropriately targeted rhinoplasty maneuvers. The patient evaluation begins with listening to the patient’s main concerns and requests. Despite the fact that most patients seek to undergo rhinoplasty for aesthetic reasons, the functional role of the nose must be kept in mind. Questions about nasal function are paramount, especially in many patients who may have previously undiagnosed functional nasal problems. By recognizing functional issues preoperatively, many patients’ nasal airways may be improved by nasal surgery Finally, as with any plastic surgery procedure, the patient’s psychological stability, ability to understand the risks and benefits of the proposed procedure, and sense of body self-image must be evaluated.

Aesthetic goals in rhinoplasty are shaped by the patient’s requests, the patient’s nasal anatomy, and the surgeon’s recommendations based on aesthetic ideals. A surgeon’s ideal rhinoplasty outcome may not always be congruent with the patient’s desires. The surgeon should discuss the rhinoplasty plan and his or her recommendations with the patient during the preoperative consultation. The surgeon should proceed further only when a clear, mutual understanding of the rhinoplasty goals has been achieved. On frontal view, an attractive nasal tip demonstrates well-defined and symmetric tip-defining points, minimal-to-no bulbosity, minimal-to-no infratip dependency, symmetric alar rims, and appropriate nasal base width. On lateral view, the nose should be adequately projected and the nasal tip should lead the nasal dorsal profile by 1-2 mm, creating a favorable supratip break. The nasal staring point (radix) should be at the level of the upper eyelid crease. On the lateral view, the columella should lead the alar rim by 2-3 mm.

Anatomic analysis of the nose relates to both the aesthetic and functional properties of the nose. Often overlooked are the posterior septal deviations, septal spurs on the nasal floor, or enlarged turbinates due to allergies. In the absence of significant nasoseptal deviation, a patient’s concern about bilateral nasal obstruction may be an indication of external valve collapse due to a flail ala. In such cases, supporting the lateral aspect of the nostril with a nasal speculum should improve subjective nasal airflow. An incompetent internal nasal valve can also create significant nasal obstruction. Patients with a narrow middle vault, a history of previous rhinoplasty, or shorter nasal bones are at higher risk for internal nasal valve problems. Palpation of the nasal bones can help determine their size and contribution to the contour of the dorsum. Nasal humps are usually osseocartilaginous with a greater cartilaginous component. The integrity of nasal tip structures and overall support mechanisms can be partially deduced from the amount of nasal tip recoil present after pressing against the tip. With a gloved finger, bimanual intranasal examination can help determine the orientation of caudal septal cartilage and the size of the nasal spine. Palpation can also help determine the thickness of the nasal skin soft tissue envelope.

Intraoperative Details

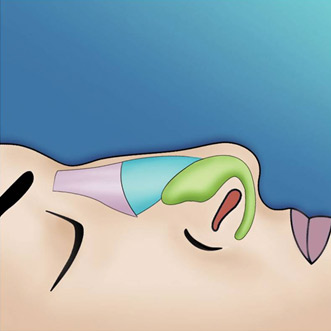

The emphasis in rhinoplasty should be on preservation, reorientation, and reshaping of cartilages as much as possible, minimizing cartilage resection to only what is absolutely necessary (Figure 1).

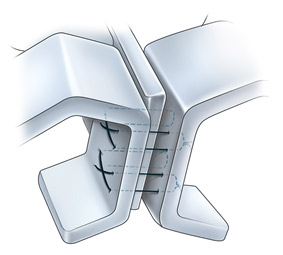

Septal incisions can be used in performing septoplasty, for harvesting cartilage, and for facilitating other corrective maneuvers in the septum. Subperichondrial flaps are raised in a naturally occurring bloodless plane, exposing septal cartilage and bone. Deviated cartilage is taken out, straightened, and placed back in the nose. Excised cartilage also may be used later for grafting purposes. Bony deviations are generally carefully excised and not replaced. To ensure proper support and to prevent postoperative saddling, a generous (>15-mm) dorsocolumellar cartilaginous strut is left behind for adequate support (see image below). The mucoperichondrial flaps are then approximated together with a running (4-0 chromic) stitch.

Stabilization of the nasal base plays an important role in nasal projection and tip support. The support of the nose has classically been divided into major and minor tip support mechanisms. The major tip support mechanisms include the length and strength of the lower lateral cartilages, the ligamentous articulation between the medial crus and septum, and the ligamentous attachment of the lower lateral cartilages and upper lateral cartilages. The minor tip support mechanisms include the cartilaginous septal dorsum, the interdomal ligament, the membranous septum, nasal spine, sesamoid complex, and the attachments of the lower lateral cartilages to the overlying skin and soft tissue envelope. Many primary noses operated on have poor projection preoperatively.

A recent study by Constantian et al. demonstrated that 66% of patients he treated had under-projected nasal tips preoperatively. Based on this study and others, inherent tip-supporting mechanisms in the majority of patients seeking rhinoplasty can be deemed to be weak preoperatively and must be fortified postoperatively to prevent any untoward squeal. Furthermore, during rhinoplasty, many maneuvers disrupt ligamentous support and consequently result in loss of tip projection.

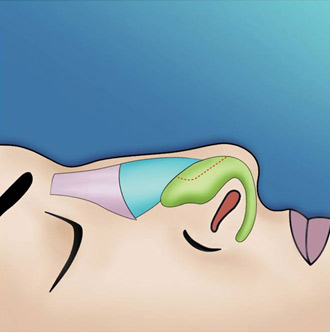

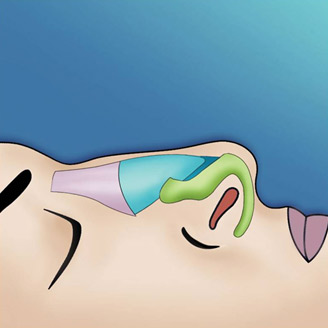

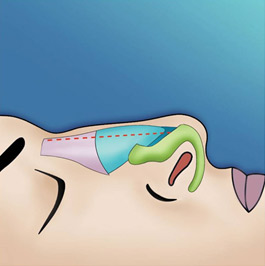

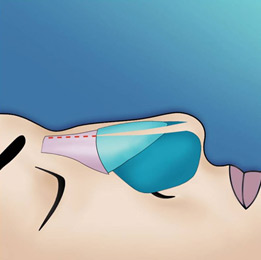

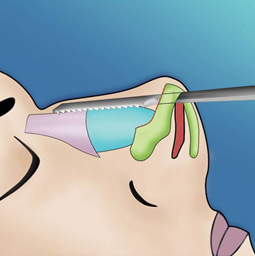

The endonasal approaches can be divided into the 2 broad categories of nondelivery approaches and delivery approaches. When planning endonasal incisions, caution must be exercised in patients with significant alar cartilage asymmetry, cephalic lateral crural positioning, previous rhinoplasty, and very thin alar cartilages. In these cases, surgeons must fashion their incisions more carefully according to the anatomy present (Figure 2). When using a nondelivery approach, the alar cartilages must be carefully palpated and outlined to avoid inaccurate cartilage resection. The basic technique for standard closed rhinoplasty remains the transcartilagenous approach. In this approach, we first locate the caudal and cephalic margins of the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage and make an incision through vestibular skin only 5 mm to 8 mm cephalic to the caudal margin of the lateral crus (transcartilaginous incision) (intracartilagenous incision) (Figure 3). With scissors, we dissect free the vestibular skin in a cephalic direction to just beyond the cephalic edge of the lateral crus (Figure 4). Then we incise the lateral crural cartilage and free the cephalic portion from its remaining soft-tissue attachments by dissecting superficial to it in the supraperichondrial plane (Figure 5,6).

Need for grafting of the lower lateral cartilages, excess projection, unusually angulated crura or severely deformed alar cartilages are an indication for a cartilage delivery approach where these deformities may be directly visualized and addressed. The delivery approach allows for direct visualization of the lower lateral cartilages, equivalent to an open technique in most cases (Figure 7). Exposure is achieved with an incision along the caudal margin of the lower lateral crura continuing medially to the medial crus on each side. It may extend along the columella as required for exposure. An intercartilagenous incision is made allowing a bipedicled flap to be delivered into the operative field to allow for necessary tip modification. The alar cartilages may now be refined with cephalic trim, intradomal, and interdomal sutures, and selectively weakened with cross hatching techniques.

The lower lateral cartilages provide much of the structural support responsible for the external shape of the nasal tip. Nasal tip support mechanisms must be strong enough to support the redraping of the soft tissue skin envelope and to resist the long-term contractile forces produced by scarring. Cephalic resection of the lower lateral cartilages can help reduce nasal bulbosity, contribute to creating a subtle supratip break, increase the pliability of the alar cartilages for other tip-defining maneuvers, and achieve small degrees of cephalic tip rotation. A point that must be emphasized is that at least 6-8 mm of alar cartilage must be preserved- more with weaker cartilages. Overresection of the alar cartilage can result in the long-term development of alar collapse, supratip pinching, bosses, asymmetries, and other undesirable results. Cephalic resection can be performed via nondelivery and delivery approaches. When using the delivery approach, commonly found cartilaginous asymmetries can be readily appreciated. When excising cartilage, focusing on how much cartilage is left behind is helpful to ensure adequate symmetry (Figure 8).

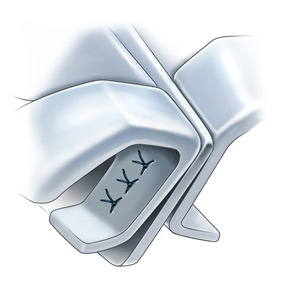

Suture fixation techniques require a delivery approach for surgical manipulation. Intradomal horizontal mattress sutures can be used to narrow the domal angle between the lateral and medial crura (Figure 9-12). When combined with a conservative cephalic trim, tip narrowing, cephalic rotation, and a slight (1-2 mm) increase in projection may be achieved. Intradomal sutures can be placed on each dome independently in a manner to maximize symmetry of the newly created domal contours. Interdomal sutures are placed in between the alar domes. Interdomal cartilages can decrease the interdomal distance, help set final symmetry between the paired domes, and add structural support to the nasal tip. The medial crura can also be suture-fixated to each other to achieve extra support, correct buckling, or align other medial crural asymmetries (Figure 13). Suture fixation can also be used to secure the alar cartilages to the caudal septum for additional support.

Cartilage grafts can be placed via a nondelivery method by creating precise pockets for placement of necessary grafts. Alternatively, suture fixation of grafts or the placement of a larger graft may benefit from the access provided by the delivery method. Various shapes of cartilage grafts can be placed into precise pockets to camouflage or augment as needed. Caution must be exercised in patients with thin skin because such grafting may show through the skin. In such cases, shaping and contouring the edges of the grafts can soften their visible outline through thin skin. In patients who are significantly under-projected preoperatively, a columellar strut may be necessary to allow for appropriate projection. The placement of columnar struts allows for increased strength in projection of the nose. There are two basic methods of securing a columellar strut. The first method is to place the strut through the marginal incision, over the nasal tip and domes, into a pocket in the columella. This method provides a moderate degree of support. The second method involves dissection through the medial crus on one side and placement of the strut between the medial crural space (Figure 14). This technique allows the strut to have a spring-loaded effect and allows for restoration or further nasal tip projection (Figure 15). Caution should be made about leaving the strut too long. The strut should not be the leading portion of the nasal tip (Figure 16). Tip grafting should be used judiciously to increase tip projection and refinement in cases of thick skin, Polly-beak deformities, revision rhinoplasty in cases of overly resected primary surgeries, nasal tip hypoplasia, the plunging tip and the cleft nasal deformity. Use in thin skinned individuals should only be performed with great caution. These grafts may be placed in precise pockets, secured under direct visualization in delivery patients or secured via a transcutaneous temporary suture in the appropriate position. In general terms, broader, thinner grafts or multiple smaller grafts will leave the patient with a more natural long term result than thicker smaller grafts. Onlay grafts are powerful tools that may be useful in camouflaging contour irregularities over the remainder of the osseocartilagenous framework. Crushed or diced cartilage grafts placed in precise pockets without overcorrection appears to be associated with a favorable long term outcome in most patients.

In patients with adequately projected nose or slightly over-projected noses, the tongue-in-groove maneuver provides powerful stabilization and additional support to the tip. The key concept is that the medial crura overlap and are fixated with the stable septum (Figure 17). The tongue-in-groove provides correction of the hanging columella, excess nasal length, and tip ptosis. The tongue-in-groove may lengthen the upper lip length and shorten the dorsal line. The overlap of medial cartilages and septum serve to augment medial crural strength.

The triple cartilage combining suture technique aims to combine the two cartilages of the medial crural with the septal cartilage. Like most nasal techniques today, it is a modification of techniques described previously. At the completion of any required septoplasty technique, retrograde dissection is performed between the medial cruras of alar cartilage to create a pocket. The medial cruras are then advanced onto the denuded caudal septum cephaloposteriorly.

The results of the initial trial placement will determine whether any caudal septal cartilage excision is necessary. The caudal septum may be variably trimmed when necessary, depending on the correction required. Once the precise desired relationship of the medial crura to the septum is obtained, these structures are fixed with two separate eight-shaped sutures placed between the medial crura and the caudal septum (Figure 18).

This eight-shaped suture is the main difference of our method and avoids making the nose too stiff. In cases of caudal septal deviation, the deviation should be corrected by freeing up the caudal attachments of the septum at the crest and spine. Once the septum has been straightened, placement of the triple cartilage combining suture adds further support to help maintain the septum in the straightened position.

Alar batten grafts vary in placement from surgeon to surgeon in cases of lower lateral cartilage weakness. Typically, the area of maximal collapse or weakness is marked preoperatively. Through a marginal incision, dissection takes place to create a precise pocket for placement of the cartilage graft. Once the batten is secured, further stabilization with additional sutures is often not necessary. Placement of alar batten will provide increased triangularity and structure to the nose and prevent the unwanted squeal of external valve collapse.

Spreader graft placement was originally conceived by Sheen as a means of improving the transition between bone and cartilage and opening the internal nasal valve. In cases of airway obstruction, the endonasal approach is the ideal placement of the graft. The submucosal placement of the graft will offer the maximal opening of the internal nasal valve. A select pocket is created in along the dorsum between the septum and upper lateral cartilage. To ensure that the pocket remains undisturbed, a suture can be placed slightly inferior to where the graft will lie.

A small freer is then used to elevate the small pocket. Placement of the graft will push the upper lateral cartilage laterally. If the pocket is precise, suture stabilization is not necessary. If the middle vault still remains narrow in relation to the nasal bone after such a maneuver, onlay grafts or an extramucosal technique may be warranted.

The nasal base, as with the rest of the nose, contributes to the functional and aesthetic properties of the nose. The degree of alar base widening and alar flaring can be influenced by many factors, including the orientation of the alar cartilages, the strength of the alar cartilages, the insertion angle of the ala onto the face, and nasal tip projection. Alar base resection is one way to narrow the base. It involves full-thickness excision of skin with its underlying soft tissue in the area of the nostril sill. A slightly more lateral placement of the excision into the insertion of the ala can also reduce excessive alar flare, in addition to narrowing the base. The imposition of the medial crura and their footplates into the nostrils can lead to an unattractively widened columellar base and, potentially, reduced airflow. Such widely divergent medial crural footplates can be brought together by suture fixation or, in very rare cases, by partial footplate amputations. Suture fixation of the medial footplates and medial crura can also be used to add support to the lower third of the nose.

Dorsal convexities are common and should be reduced conservatively (Figure 19). Access to the nasal dorsum can be attained via previously placed intranasal incisions. The cephalad skin and soft tissue envelope can be elevated using a No. 15 blade or scissors over the middle vault perichondrium and bony vault periosteum. Nasal hump reduction is begun with scalpel resection of the cartilaginous part of the nasal hump (Figure 20). The line of hump resection is developed with the knife, and then it is continued into the nasal bones using an osteotome (Figure 21). Only a small amount of bone should be removed because additional reduction can be achieved using appropriate rasps (Figure 22). Rasps can be used to further smooth the dorsum. Most nasal hump reductions result an intraoperative open roof deformity. An open roof deformity is formed when an osseocartilaginous hump is removed, exposing the unroofed nasal septum, upper lateral cartilages, and lateral nasal bones. This open roof can be closed using medial and lateral osteotomies to reconstitute a continuous dorsal bony pyramid.

The middle vault occupies an important functional and aesthetic role in the nose. The internal nasal valve is found in the middle vault in the area where the upper lateral cartilages and septum meet. The internal nasal valve represents the area of greatest resistance of nasal airflow. If its function is compromised, nasal obstruction can result. Most dorsal convexities (humps) usually have a significant cartilaginous component. Any hump reduction may destabilize and compromise the attachment of the upper lateral cartilages, leading to internal valve incompetence. Postrhinoplasty nasal valve compromise may result from scarring, inferomedial displacement of the upper lateral cartilages, or resection of upper lateral cartilages. Unstable upper lateral cartilages can result in long-term aesthetic complications such as an inverted-V deformity, nasal sidewall asymmetries, middle vault narrowing, and even saddling. Spreader grafts can be used to minimize or correct such problems. Spreader grafts can be placed through subperichondrial tunnels between the septum and the upper lateral cartilages. Properly placed spreader grafts serve to preserve or increase middle vault width, expand the cross-sectional area of the internal nasal valve, and decrease the risk of inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages.

Osteotomies are controlled fracture lines created by the surgeon to mobilize and reshape nasal bone segments into the form desired. Medial osteotomies are started from the vertical midline, then, at a 20° angle, they are obliquely curved toward (but not higher than) the medial canthus. If a sizable dorsal hump resection has been performed, then medial osteotomies may not be needed because the medial attachments of the nasal bones have already been interrupted. Osteotomies on the lateral nose can be further divided into lateral and intermediate osteotomies. Lateral osteotomies, when combined with medial osteotomies, can be used to narrow the bony vault, correct bony asymmetry, enhance nasoorbital sidewall shadowing, and slightly increase nasal bony vault projection. Intermediate osteotomies are placed higher than lateral osteotomies and are used to further mobilize the nasal bones, especially in cases of significant asymmetry. Intermediate osteotomies can also be performed to further narrow a wide bony pyramid. By convention, the position of lateral osteotomies (high vs low) is defined based on a supine patient in relation to the ceiling (see image below). Curvilinear lateral osteotomies are started at the pyriform aperture where a high-low-high osteotomy line is created up to the medial canthal line. Mucosal incisions and osteotomy site mucoperiosteal flap elevation are not required when a 3-mm or smaller osteotome is used. Lateral osteotomies are initiated at the pyriform aperture or just above the attachment of the inferior turbinate to the ascending process of the maxilla in order to prevent inferior turbinate destabilization. Osteotomies should not extend more cephalad than the harder bones found at the approximate level of the medial canthi. Extending the osteotomies further cephalad than the medial canthal line does not yield much additional cosmetic benefit, but it does significantly increase the risk of a “rocker deformity.” The initiating fracture line of the lateral osteotomy should also be placed low enough to allow for a large lateral nasal wall infracture. This decreases the chance of creating a palpable step deformity, which can occur when lateral osteotomies are positioned too high. The newly osteotomized bones should be freely mobile upon manual palpation, but they should be splinted by the undisturbed periosteum and soft tissues that remain attached to the bony fragments. The ultimate goal of combined medial and lateral osteotomies is to create a continuous fracture line so that the shape of the nasal pyramid can be reset to the surgeon’s liking. Percutaneous osteotomies using a 2-mm osteotome through a small skin-stab incision can be used to complete osteotomies in areas not adequately fractured and mobilized.

Postoperative Details

Postoperative care for rhinoplasty patients should maximize patient comfort, reduce nasal swelling, and provide immobilization and stabilization of the nose. Immediately after the rhinoplasty, Steri-Strips or strips cut from surgical brown tape are applied to the nose to reduce edema, securely immobilize loose bone segments, and pad the nasal cast. The surgeon can use a taping process to help influence favorable healing and scarring of the nose. The nasal cast is usually left on for 5-6 days. The patient is instructed to not remove or touch the nasal cast and to keep it dry. Nasal taping and casting can also serve to allay the negative psychological impact of immediate postrhinoplasty bruising and edema on the patient. Some advocate an extended period of nasal taping for several weeks to influence favorable healing.

Nasal packings and systemic antibiotics are not routinely used. If nasal packs are placed, oral antibiotics are started to reduce the risk of toxic shock syndromePlastic or silicone intranasal splints are placed in patients who undergo septal work or those who may be at risk for developing intranasal synechiae. With an uncomplicated septoplasty, the intranasal splints are removed in 5-6 days.

Patients with intranasal splints are encouraged to use normal saline irrigations several times each day to cleanse the intranasal cavity. Intranasal application of topical antibiotic ointment using a cotton-tipped applicator may be recommended in the motivated and coordinated patient. Prior to surgery and once again prior to discharge, a detailed instruction sheet outlining recommendations is provided to the patient. Highlights of a few of these postrhinoplasty recommendations are included in follow-up care.

Patients are educated preoperatively regarding the temporary postrhinoplasty periorbital and nasal swelling and discoloration that may occur. Besides providing emotional support during the immediate postoperative period, remind the patient again that edema and ecchymosis usually clear within 2-3 weeks. In certain patients, a complete resolution of edema may take as long as 6 months. Supratip edema can be treated with small injections (0.3 mL) of Kenalog 20 starting at week 3 and continuing once a month. These injections must be placed deep to minimize the risk of dermal atrophy and tissue loss.

After cast removal, the nasal skin is gently cleansed with an adhesive solvent and gauze. At this visit, photographs may be taken to document the early postoperative surgical result. These early photographs may assume vital medicolegal importance if the patient’s surgical result is compromised by subsequent trauma. Analysis of early postoperative results is also of educational value to the surgeon. The author likes to arrange visits 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after the operation. After that, annual visits are encouraged and photographs are taken to document the subtle changes in nasal appearance that inevitably occur with time. Observing and studying these changes (both favorable and unfavorable) provides the surgeon with an invaluable education. Such an approach can allow surgeons to continuously analyze their techniques to anticipate, control, and favorably affect long-term rhinoplasty healing.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the debate over whether external or endonasal operations are superior is inconsequential. Long-term surgical results, both aesthetic and functional, are the standards by which all rhinoplasty operations are judged.