Abstract

What holds true for every surgery is also essentially true of rhinoplasty. Knowledge about and awareness of complications and the possible means to handle them is essential for every rhinoplasty surgeon. Referring to the time of occurrence, complications can be divided into early and late complications. Early complications such as bleeding or infection are rare; late complications related to postoperative failure to achieve the desired aesthetic or functional objectives are much more common. In this chapter the author will give an overview of the most frequent complications after rhinoplasty and describe prevention and techniques to correct the complication.

Introduction

Rhinoplasty is still one of the most challenging procedures in facial plastic surgery. With surgical experience and the right surgical techniques, results are for the most part satisfactory and patients are pleased. However, like in any other surgery, complications do occur; awareness of them and the knowledge as to how to treat them is essential for any rhinoplasty surgeon.

Complications can be divided into early and late complications; this refers to the time when they occur. Early complications may develop during the operation itself or can occur up to 4 weeks post-op when the initial healing period is finished. All other complications can be regarded as late complications.

Basically early complications such as bleeding or infection after rhinoplasty are rare, however, swelling around the back of the nose can cause ear pressure, knowledge about their treatment is crucial for any rhinoplasty surgeon or ENT Specialist. According to the literature, extremely rare fatal complications have also been reported, and just to be aware of the existence of these serious complications may help one to avoid them1.

Late complications however are much more likely to occur. They are generally related to postoperative failure to achieve the desired aesthetic or functional objectives. Precise preoperative analysis of the problem as well as appropriate surgical techniques with continuous control of each and every surgical step allows the surgeon to reduce the number of such complications.

Early complications

Hemorrhagic complications

Postoperative Epistaxis

Despite the fact that basically any osteotomy performed during a rhinoplasty may cause postoperative epistaxis due to damage to branches of the facial or anterior ethmoidal artery, this is a very rare complication. The incidence of excessive bleeding reported in the literature ranges from 2% to 4%2. Bleeding can occur immediately after surgery or any time following for up to two weeks. Treatment is usually conservative with endonasal packing for 48 hours; in rare cases of recurrent bleeding, surgical correction involving endoscopic identification and coagulation of the site of bleeding is required. In the case the identification is not possible, surgical obstruction of the territorial artery is necessary.

In order to prevent this complication, minimizing trauma with the utilization of micro-osteotomes for lateral and oblique osteotomies is recommended3,4 .

Septal hematoma

Separating the mucoperichondrium blades of the quadrangular cartilage for correction of deformities or for harvesting cartilages is a routine part of rhinoplasty. At the end of the procedure the mucosal flaps are put back, closed again, and fixed either with suturing, fibrin glue or nasal packing. When the fixation of the flaps is insufficient, bleeding between the two mucoperichondrial flaps creates a septal hematoma.

Usually 3 to 5 days after surgery massive swelling and protruding of the septum into both nasal cavities with blocking of the airway occurs.

Treatment is in all cases surgical with wide opening of the haematom cavity, removal of the entire hematoma, and endonasal packing for 48 hours combined with parenteral broad spectrum antibiotics.

Infectious complications

Infectious complications in septorhinoplasty produce inflammatory infiltration of the overlying skin, nasal vestibule or columella, or form a granuloma within an incision1,5. These limited infections generally respond well to systemic antibiotic therapy. Abscesses have to be treated additional with incision and drainage.

There is frequent discussion whether peri-operative antibiotic treatment is necessary in routine septorhinoplasty. This may depend on the postoperative patient management, and if patients are not under constant supervision in hospital but instead undergo surgery in outpatient facilities, antibiotic prophylaxis helps to prevent infectious complications.

Abscesses of the nasal septum are the result of untreated septal hematomas6. Additional to the symptoms of the septal haematoma, two days later, 7 to 8 days after surgery, patients suffer from a rise in body temperature and increasing nasal pain. The therapy required is immediate surgical intervention with opening of the septum, removal of all pus, nasal packing and parenteral antibiotic treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics parenterally.

Poor wound healing

Problems with the wound healing are caused by infection, bleeding or insufficient blood supply of the overlying skin. Naturally the blood supply of the nose is very good, therefore these complications are rare. Reasons for insufficient blood supply may be systemic like diabetes, or local damage due to poor surgical technique or excessive cauterization. If skin necrosis occurs, satisfactory cosmetic correction is rather difficult with skin transplants or with composite grafts. Absolute care has to therefore be taken to avoid these complications.

Late Complications

Basically every single step during a septorhinoplasty procedure can lead to a late complication, either from a functional or cosmetic point of view or as a combination of both.

In order to get a better overview, late complications will be discussed according to the different areas that are usually corrected while performing a septorhinoplasty.

Table 1 gives an overview of the different surgical areas and possible complications.

Table 1:

| Surgical Area | Possible complication |

|---|---|

| Nasal septum | Dorsal saddling |

| Columella retraction | |

| Septal perforation | |

| Nasal dorsum | Dorsal irregularities |

| Mucosal dorsal cyst | |

| Overresection | |

| Pollybeak | |

| Bony pyramid | Deviation |

| Open roof | |

| Staircase phenomenon | |

| Osseocartilaginous junction and cartilaginous pyramid | Inverted V deformity |

| Alar insufficiency | |

| Nasal tip | Underrotated and droopy tip |

| Overrotated tip | |

| Asymmetry |

Nasal Septum

Loss of septal support

It is certainly true that the dorsal and caudal border of the quadrangular cartilage provides important support to the nasal dorsum, the nasal tip and columella. In order to preserve this support, we try to leave a strong L-strut untouched when harvesting cartilage or correcting deformities of the nasal septum.

Dorsal saddling

Etiology:

Weakening of the mechanical stability of the dorsal part of the L-strut may occur due to excessive resection while harvesting septal cartilage, especially in combination with hump resection. Usually septal work is performed at the beginning of the procedure, therefore what seems to be a sufficient dorsal strip at the end of septal work and cartilage harvesting may in fact be too small and thin after hump resection. The same holds true with posterior chondrotomy. Care has to be taken not to extend the incision too far up in the direction to the nasal dorsum when hump resection or reduction of the dorsum is planned.

It may also be that the L-strut itself is deviated and has to be corrected. We have to be aware of the fact that every surgical intervention to straighten the cartilage weakens its mechanical stability.

Symptoms:

Depending on the degree of dorsal saddling, the deformity is mainly cosmetic or combined cosmetic and functional due to widening of the internal nasal valve.

Prevention:

Preservation of a strong L-strut not less than half an inch long with stable connection to the bone in the K-area and to the nasal spine. In case the integrity of the L-strut has to be interrupted to correct cartilage deviation, e.g. with incision or scoring, an additional support is necessary.

This can be provided by additional grafts like spreader grafts or by supporting the cartilage with a resorbable PDS plate that stabilizes the cartilage until healing.

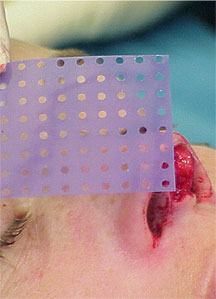

The PDS flexible plate (Fig1) is produced by Johnson & Johnson and is a completely resorbable polydioxanone plate. It comes in various sizes and gauges. In my experience, for the nasal septum the thinnest plate ZX8, which is only 0.15 mm thick, is preferable. It comes with perforations that lead to tissue ingrowth and ensure good fixation and cartilage nutrition7,8.

The plate can be cut to the desired size with scissors, implanted on one side of the cartilage and fixed in place with sutures (PDS 5/0) to the cartilage. The surgical technique is described below.

Correction:

In cases with slight saddling without any functional problems, a cosmetic correction with an onlay graft usually is sufficient. The graft can be harvested from the auricular concha and placed in a precise pocket using an endonasal approach.

In cases with severe saddling and functional problems, a reconstruction of a stable and straight septum that corrects the saddle deformity and the nasal valve at the same time is required. Although auricular conchal cartilage usually is not used as graft material for septal reconstruction, in combination with the PDS plate it is a recommendable graft for that purpose10.

Surgical technique of septal reconstruction with auricular cartilage and PDS plate:

Surgery starts with the harvesting of the auricular conchal cartilage as described by Nolst Trenité9. After a skin incision on the posterior side, posterior perichondrium and cartilage are incised in a line just below the anthelix. Next blunt subperichondrial tunneling is carried out on the anterior side of the cavum and cymba conchae followed by dissection on the supraperichondrial posterior side. After incision of the cartilage lateral to the ear canal, leaving a 3mm strip to avoid stenosis of the meatus acusticus externus and the radix helicis intact, the entire piece of cartilage is removed and put into saline solution. After meticulous hemostasis, the skin incision is closed with 5/0 atraumatic suture in single stitches. Carefully applied conchal packing with through and through mattress sutures for 4 days will prevent hematoma.

The rhinoplasty starts with an open approach. After the broken columella incision, marginal incisions and the decollement of the tip and dorsum, the medial crura of the lower laterals are separated in order to reach the caudal border of the nasal septum. The septal cartilage is dissected free on both sides and the mucosal blades are separated as far posteriorly as possible in order to be able to reconstruct a strong cartilaginous septum.

Next the plate is put into the nose to get an idea of the needed size. In the dorsal direction, the new septum should be big enough to correct the dorsal saddling, and in the caudal direction it should reach the medial crura. Then the PDS plate ZX8 is cut to the needed size of the new septum. Now the PDS plate has to be covered with cartilage. The remnants of septal cartilages and the harvested conchal cartilage are arranged on the plate so that the strongest and biggest pieces are located in the area of the L-strut. Because we always have to keep in mind that the foil will be completely resorbed after 5 months – it therefore only stabilizes the cartilages but does not replace it. When the arrangement is satisfactory, the cartilage pieces are sutured to the PDS plate with PDS suture material one after the other. Care has to be taken that there are no gaps left between the cartilages.

Finally the reconstructed septum consisting of cartilage on one side and a PDS plate on the other side is reimplanted between the two mucoperichondrial layers. The fixation of the reimplanted graft start with sutures to the upper laterals in order to reconstruct the nasal valve. Since the dorsal border of the reimplanted graft is higher than it was before, the upper laterals have to be “lifted up”. Therefore the mucosal lining on the endonasal side has to be dissected free as far as needed so the cartilages can be lifted up to the new dorsal border. Then the dorsal septal border is sutured to the lifted upper laterals. The next step is the suture fixation to the periostium of the anterior nasal spine to prevent a posterior rotation of the septum. Finally the mucoperichondrial blades are put back and fixed with transseptal mattress sutures.

Since the reconstructed septum was made longer in caudal direction, the medial crura of the lower laterals are now sutured to the new caudal septal border, similar to the tongue in groove technique. This yields extra fixation of the septum and builds strong tip support (see video).

Video:

Part I shows the opening of the septum in a patient with dorsal saddling after 2 septal surgeries. The remaining septal cartilage is week, deformated and has no supporting function. It is harvested and later used for construction of spreader grafts.

| Video Part I |

Part II shows the creation of a new septum of autologous auricular cartilage and the application of spreader grafts made of septal remnants.

| Video Part II |

Part III shows the reimplantation into the nose.

| Video Part III |

Fig 2 and b show a young lady following rhinoplasty elsewhere four years ago. She was concerned about the unnatural look of her nose and the tumor like lesion on the dorsum. Functionally she suffered from breathing problems due to a high septal deviation.

Surgical Procedure:

Open rhinoplasty approach, Resection of the granulomas on the dorsum, concha cartilage harvesting, septal reconstruction with the remnant of septal and conchal cartilage and PDS plate ZX8, camouflage of the dorsum with Fascia temporalis( Fig 3a,b and 4 a,b).

and conchal cartilage sutured to the PDS plate ZX8

Columella retraction

Etiology:

Retraction of the columella always means loss of caudal septal support.

Prevention:

Either during septoplasty or septorhinoplasty, care should be taken to be very conservative with resection of the caudal septal border. In case of deviation or subluxation, the caudal part of the septum should only be dissected free, realigned to the midline and sutured to the periostium of the anterior nasal spine.

In case only the caudal septal support missing, the typical symptoms are drooping tip and retracted columella. These cosmetic deformities are often combined with breathing problems11.

Correction:

Correction is possible with all techniques that reconstruct a strong caudal septum or strengthen tip support like caudal septal extension graft or a strong columella strut resting on the anterior nasal spine12,13. Usually with the caudal septal extension graft, the difficulty lies in the fixation of the cartilaginous graft to the remnant of septal cartilage end to end; this is not possible with cartilages. This fixation can be solved with an extra strut to stabilize the cartilages. Due to its position, this strut however may lead to stenosis of the interior nasal valve.

In my experience a safe and easy method is caudal septal extension graft with PDS plate10.

Starting from an open approach, the medial crura of the lower laterals are separated. After separating the soft tissue of the membranous septum, the caudal septal border is reached and the quadrangular cartilage is dissected free on both sides. For reconstruction of the caudal septum, a stable cartilaginous graft is needed, created from the posterior part of the quadrangular cartilage if possible, but most of the time from auricular cartilage. Then a PDS plate ZX8 is taken and cut to the needed size so that it covers, in posterior and dorsal directions, the remnant of the septal cartilage, caudally reaches the medial crura and in dorsal direction the anterior septal angle. Next the caudal parts of the plate are covered with the cartilage graft and sutured together with resorbable suture material, usually PDS 5/0. Then the plate is implanted into the septum so that the free part of the plate lies beneath the remnant of the septal cartilage, and the cartilage graft lies end to end to with septum. Next the plate is sutured to the cartilage, also with resorbable sutures. Subsequently the mucosal flaps are closed and fixed with transseptal mattress sutures. Finally the medial crura are fixed to the newly created caudal septal border in the desired position.

Septal perforations

Etiology:

Unfortunately the most common reason for septal perforation is previous septal surgery. Perforations may occur after related untreated tears in the mucosa14.

Symptoms:

The symptoms of nasal septal perforation depend on the localization and size of the perforation. Those in the more posterior regions frequently are completely asymptomatic and are often discovered by chance during routine examinations.

The symptoms of perforations in the more anterior parts of the septum are dependent on the size. Small perforations often lead to whistling sounds which can be annoying for the patient. When they are larger than 5mm in diameter, they can lead to crusting, bleeding and repeated epistaxis from the borders of the perforation. Symptoms worsen relative to the size of the perforation.

In large perforations, the missing septal cartilage may result in loss of the supporting function of the nasal septum and cosmetic deformities of the external nose like saddling of the dorsum, loss of tip support or retraction of the columella.

Prevention:

Corresponding tears in the mucosa must always be sutured properly and supported with a suitable piece of normal or crushed cartilage in order to avoid postoperative perforation. Basically the posterior parts of the nasal septum as the harvesting site for cartilage grafts should be routinely supported with crushed cartilage remnants in order to support the mucosal flaps, prevent septum vibration and make later surgical intervention easier.

Surgical Correction:

The many years of experience of many authors has shown that a perforation closure with endonasal mobilization of the bilateral mucosal flaps combined with an interpositum provides the best functional results. Nowadays, with the great popularity of open rhinoplasty, this approach offers the significant advantage of excellent visualization which is also useful for septal perforation closure14,15.

In order to facilitate a sometimes surgical challenging procedure, the author recommends his own modification to the septal perforation closure procedure with the use of a PDS flexible plate.

The procedure begins with the harvesting of auricular conchal cartilage as usual9. Surgery in the nose starts with an open rhinoplasty approach. After separation of the medial crura from the lower laterals, we reach the caudal end of the septum. Starting from here the entire cartilaginous septum,as well as the anterior osseous sections are dissected. The upper lateral cartilages are divided from the dorsal septal border. This gives an excellent exposure to the perforation and the remaining cartilage and mucoperichondrium, not only in cranial and caudal but also in anterior and posterior direction.

After elevation of the mucoperichondrium from the entire septum the dissection is continued and the mucoperichondrium is elevated from both nasal floors up to the insertion of the inferior turbinate and underneath the upper laterals.

Next incisions parallel to the septum are performed underneath the inferior turbinate and underneath the upper laterals, thus creating bipedicled mucosal flaps that are sufficiently mobile. Then the mucosal defects are closed with resorbable sutures.

A PDS flexible plate ZX8 is cut into the size of the septal cartilage. In order to create an interpositum, a piece that exactly matches the size of the cartilaginous defect is cut out of the harvested auricular conchal cartilage.

If the auricular cartilage is not straight enough, this may be corrected by scoring (multiple parallel superficial incisions) on the concave side. Then the cartilaginous interpositum is positioned in the perforation and the PDS plate is also inserted beside the septum on one side. The graft is primarily fixed to the PDS with one suture (e.g. PDS 5/0); this guarantees an exact placement. Then the PDS plate can be removed together with the interpositum and the fixation of the graft with further sutures can be completed outside the nose as this is easier. Then the PDS with the cartilage graft is reimplanted into the nose, with the PDS lying on one side of the septal cartilage and the conchal cartilage graft exactly at the location of the perforation (Fig 7 a,b)

The PDS flexible plate is then sutured to the septal cartilage with two or three resorbable sutures.

In order to reconstruct the internal nasal valve, the upper laterals are sutured back to the dorsal septal border and the PDS plate. The next step is the transseptal mattress suture to fix the septal flaps and to prevent hematoma. From the remaining conchal cartilage, a columella strut is created and sutured between the medial crura of the lower laterals as usual. Finally the skin incisions are closed. Endonasal packing is not necessary. The nose is externally protected with Steri-Strip and a Denver metal splint for 6 days.

Nasal dorsum

General Considerations:

Alteration of the nasal dorsal line is one of the most common surgical goals in primary rhinoplasty and can involve reduction or augmentation.

Even though a hump resection is an absolutely routine procedure during primary rhinoplasty and seems so easy to perform, sometimes undesired results occur.

The most common complications after reduction of the nasal dorsum follow.

Dorsal Irregularities:

Especially in thin skin patients only tiny irregularities of the bony or cartilaginous dorsum may cause an irregularity in the dorsal line. This may be remnants of bone after hump resection or rasping, or insufficient resection of an upper lateral cartilage.

Prevention:

In order to avoid irregularities of the dorsal line in the area of the bony pyramid, one of the crucial points besides precisely carried out technique is the sharpness of the osteotomes. Only a really sharp osteotome is able to remove the bony hump exactly at the desired level without bony irregularities.

Irregularities in the area of the cartilaginous pyramid most of the time occur if the resection line of the cartilaginous hump is not checked carefully enough for irregularities at the end of the hump resection.

Correction:

Rasping of bony irregularities can be performed with traditional rasps or a power rasp16. Cartilaginous irregularities have to be excised and additional camouflage grafts from crushed cartilage or temporalis fascia are sometimes required (Fig 8 a,b,c and 9 a,b).

Mucous dorsal cyst:

In some cases dorsal irregularities may be caused by mucous cyst.

Etiology:

Most nasal cysts are attributed to entrapment of nasal mucosal remnants in the subcutaneous space. An entrapped piece of nasal mucosa is assumed to be the cause of the cyst. These cysts can cause permanent deformity17.

Prevention:

Careful dissection in the right surgical plane and the avoidance of excessive damage to nasal mucosa should prevent the development of nasal cysts.

Correction:

The resection is easier from an open rhinoplasty approach since it provides better overview. The problem is the scaring of the overlying skin and soft tissue; this makes preparation difficult.

Overresection:

Excessive resection of the nasal dorsum leads to an undesirable profile and from a psychological point of view may also lead to a loss of confidence.

Prevention:

Exact preoperative planning regarding the amount of resection with respect to patient desires and also facial harmony and ethnic features. Excessive resection can also be avoided by keeping in mind the variable thickness of the skin of the nasal dorsum. When reducing a hump, the plane of resection must be slightly biphasic, taking care to leave a slight hump at the rhinion where the skin is thinnest.

Correction:

Correction only is possible with augmentation of the excessively resected part. This may also happen during the primary rhinoplasty when the surgeon realizes the amount of resection was too much. The resected hump can be thinned and re-implanted.

Correction during a revision surgery needs augmentation with grafts. Depending on the preference and availability, they may be autologous cartilage grafts from the septum or concha auriculae, rib cartilage, homologous grafts with irradiated rib cartilage or various alloplastic materials.

The authors first choice is autologous material, primarily septal or conchal cartilage. The implantation usually is performed by endonasal approach into a precise pocket. Important for long-term success is the meticulous shaping of the graft, and in thin skin patients additional camouflage grafts. An excellent material for camouflage is temporalis fascia. It can easily be harvested and prevents shining through of cartilage borders or small irregularities after shrinking of the soft tissue.

Pollybeak:

Polly beak deformity is a complication of rhinoplasty defined by the typical appearance of a dorsal nasal convexity resembling a parrot’s beak.

In order to be able to correct this deformity, knowledge of the etiology and exact preoperative analysis is necessary.

Basically there are three different reasons for development of a polly beak: cartilaginous, soft tissue and relative4,18 .

Cartilaginous pollybeak

Etiology:

Insufficient resection of the cartilaginous dorsum (upper laterals or dorsal septum or both) during hump resection.

Prevention:

Adequate resection of the cartilaginous dorsum during hump resection, meticulous checking of the height of the upper laterals and the dorsal septum as well as checking of the dorsal line with a wet gloved finger after re-draping of the soft tissue.

Soft tissue pollybeak – thickening of the supratip area due to scar tissue

Etiology:

The cause is traumatizing of the soft tissue by preparation in the wrong surgical plane

Prevention:

Observance of the right surgical plane and exactly hugging the cartilage while lifting up the soft tissue envelope not only reduces bleeding but also avoids excessive scar formation.

Therapy:

Conservative treatment with subcutaneous Triamcinolon may be helpful.

Relative pollybeak

Etiology:

Loss of tip projection with drooping tip creates a relatively fullness in the supratip area.

Prevention:

Preserve or restore tip support mechanisms (Table 2).

Correction:

Restoration of a strong tip support is required, e.g. with tongue in groove technique. Further resection of the cartilaginous dorsum has to be avoided in all cases!

Bony pyramid – complications after osteotomies

Postoperative deviation of the bony pyramid

Etiology:

Either insufficient mobilization of the bone after an osteotomy, or lack of realization of preoperative existing asymmetry of the nasal bones that would have made an intermediate or multiple osteotomies necessary.

Prevention:

Exact preoperative analysis of the bony pyramid, possible asymmetries and planing of potentially needed osteotomies.

Utilization of micro-osteotomes as then it is not necessary to dissect the periostium, and even with multiple osteotomies the bony fragments are supported by the periostium and there is no danger of loosing bone. Especially in post-traumatic deformities, multiple “tailor made” osteotomies are necessary to straighten the bony pyramid19.

Open roof deformity:

Patients with an open roof deformity show a widened nasal bridge with the nasal bones stand apart, not closed as in a gable, and show their dorsal borders through the skin. The nasal septum in between the bones can be palpated and sometimes also seen.

Etiology:

Inadequate mobilization of the nasal bones after hump resection, leaving the nasal roof open.

Prevention and Correction:

The lateral osteotomies should be combined with medial oblique or transversal osteotomies in order to be able to properly medialize the nasal bones after hump removal. After infraction of the nasal bones, the proper position should be checked by re-draping the skin and palpating carefully for any irregularities.

Staircase phenomenon

Etiology:

A palpable and sometimes also visible deformity of the lateral wall of the bony pyramid is caused by a lateral osteotomy performed too high.

Correction:

Correction is easy with another lateral osteotomy carried out lower than the previous one.

Osseocartilaginous junction and cartilaginous pyramid

Inverted V deformity – middle vault collapse

Etiology and symptoms:

The middle nasal vault is composed of of the upper lateral cartilages which are supported superiorly by the nasal bones and medially by the cartilaginous septum. The dorsal edge of the upper lateral cartilages is attached to the dorsal septal border by end to end apposition. The attachment of the caudal end of the upper lateral cartilages to the septum forms an angle of approximately 15 degrees. This angle forms the internal nasal valve, an important structure in nasal function.

Hump resection in patients with short nasal bones may lead to middle vault collapse because the short bony vault does not adequately support the cartilaginous vault. The lateral walls fall in, leading to cosmetic and functional sequelae. In frontal view, a cave in of the lateral walls and delineation of the caudal edges of the nasal bones leading to a deformity in the form of an inverted V appears.

Prevention and therapy is simple and clear with the insertion of spreader grafts20. They can be created from septal, autologous conchal or rib cartilage. Inserted and sutured between the dorsal border of the upper laterals and the cartilaginous septum, they reconstruct the middle vault and open the nasal valve, correcting the cosmetic deformity and functional problems in one procedure.

Alar insufficiency

Etiology and prevention:

Alar insufficiency means unstable alar sidewalls that lead to external nasal valve stenosis by collapsing on moderate or deep inspiration. Alar insufficiency as a surgical complication mainly occurs after weakening of the lateral crus of the lower laterals by excessive trimming or division. If division techniques are performed in order to create major changes in tip projection or rotation instead of resection, overlapping of the cartilage fragments should be performed.

Correction:

Strengthening of the weak lateral nostril sidewall may be achieved by different procedures e.g. insertion of alar batten grafts or suture fixation of the lower lateral cartilage to the piriform

aperture21,22.

Nasal tip complications

Understanding the nasal tip structures and support mechanisms is crucial for every good long-term rhinoplasty result. Even if we do not want to alter the shape of the tip, every single rhinoplasty approach destroys one or more tip support mechanisms (Table 2) which have to be restored in order to avoid nasal tip complications.

Table 2: Tip support mechanisms

| Major tip support mechanisms | Minor tip support mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Size, shape and strength of the lower lateral cartilages | Connection between the domes |

| The attachment of the lower lateral to the upper lateral cartilages | Cartilaginous septal dorsum |

| Medial crura footplate attachment to the caudal septum | Sesamoid complex |

| Caudal septal border | Nasal spine |

| Membranous septum |

Furthermore it is necessary to have a fundamental understanding of the lower lateral cartilages and their influence on the shape of the nasal tip. Models like the tripod theory or the M-arch theory enable the surgeon to correct tip deformities in the desired way during rhinoplasty 22,24,25.

Despite thorough understanding of the anatomy and tip dynamics, one can never be absolutely sure about healing and postoperative scaring, and we may still be confronted with patients with complications after tip surgery.

There are three different categories: underrotation and droopy tip, overrotated tip and asymmetric tip.

Underrotated and droopy tip with acute nasolabial angle

Etiology:

Loss of tip support either through lack of restoration of the support of the medial crus or resection of the caudal septum.

Correction of a droopy tip:

Whereas in primary rhinoplasty changing of the lateral crura as the two lateral legs of the tripod is the main procedure to correct a droopy tip, in revision rhinoplasty strengthening of the medial leg of the tripod in order to reconstruct tip support should be the technique of choice. This has to be quite strong in order to achieve a good long-term result. A reliable technique is to strengthen the caudal septum with a caudal septal extension graft and subsequent fixation of the medial crura to the caudal septum as in the tongue in groove technique26,27.

Overrotated tip

Etiology:

Overrotation can be the result of excessive resection of the anterior septal angle or the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages.

Correction:

Depending on the etiology and the degree of excess rotation a correction can be quite challenging, require lots of grafts and be limited by the soft tissue envelope. Therefore excessive resection of upper lateral cartilages should be avoided in all cases! Counterrotation of the nasal tip can be achieved, for example, with elongated spreader grafts pushing the tip down (Fig 10 a,b and 11 a,b) combined with strengthening of the lateral crura with alar strut grafts. An extra elongation may be achieved by insertion of a shield graft.

Miriam Dr. Boenisch PhD 08/12/2010 18:43

Literatur caudal septal extension und bilder

Asymmetric tip:

Prevention:

Asymmetries my occur due to asymmetric resection of the lower lateral cartilages, asymmetric tip sutures, iatrogenic tip bossae, incorrect insertion of a columella strut or simply by missed correction of preoperative existing asymmetries.

For correction of tip asymmetries, an open rhinoplasty approach is recommended in order to be able to identify the pathology directly. If possible, the lower lateral cartilages have to be realigned in a symmetric way and fixed with sutures. Sometimes missing parts of the lower laterals have to be reconstructed with grafts, sometimes symmetry can only be achieved with the use of camouflage grafts.

Final Conclusion:

Rhinoplasty is still one of the most challenging procedures in facial plastic surgery. With surgical experience and the right surgical techniques, results are most often satisfactory and patients

are satisfied. However, as in any other surgery, complications do occur and the awareness of them and the knowledge as to how to treat them is essential for any rhinoplasty surgeon.

Concerning early complications, the surgeon has to make dispositions, to ensure diagnose of a complication as soon as possible, so treatment can start without delay.

Concerning late complications, careful preoperative analysis and surgical planing as well as selection of the appropriate techniques is essential. During surgery, the surgeon should check the efficiency and result of every single step of the procedure. With this strategy, the surgeon may be able to realize and correct eventual problems possibly leading to late complications even during the primary rhinoplasty, thus avoiding the need for revision surgery.

References:

- Lawson W, Kessler S, Biller HF: Unusual and Fatal Complications of Rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 1983;109:164-169

- Tamerin JA: Management of hemorrhage post rhinoplasty. NY State J Med 1967;67:550-555

- Tardy ME Jr et al: Micro-osteotomy in Rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 1984;1: 137-145

- Nolst Trenité GJ: Surgery of the osseocartilaginous vault. In: Rhinoplasty.A practical guide to functional and aesthetic surgery of the nose. 3rd edition. Kugler Publications, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005; Chapter 11:97-115

- Rettinger G, Steininger H: Lipogranulomas as Complications of Septorhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997; 123:809-814

- Rettinger G, Kirsche H: Complications in septoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 2006; 22: 289-297

- Boenisch M, Hajas T, Nolst Trenité GJ: Influence of Polydioxanone Foil on Growing Septal Cartilage in an Animal Model. New Aspects of Cartilage Healing and Regeneration. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003; 5: 316-319

- Boenisch M, Nolst Trenité GJ: Rhinoplasty. A practical guide to functional and aesthetic surgery of the nose. 3rd edition. Kugler Publications, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005; Chapter 25: 257-284

- Nolst Trenité GJ: Grafts in Nasal Surgery. In Rhinoplasty.A practical guide to functional and aesthetic surgery of the nose. 3rd edition. Kugler Publications, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005; Chapter 7: 49-67

- Boenisch M, Nolst Trenité GJ, Septal Reconstruction using PDS plate. Arch Facial Plastic Surg 2010;12: 4-10

- Petroff MA, McCollough EG, Hom D, Anderson JR: Nasal Tip Projection. Quantitative Changes Following Rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:783-788

- Spörri S, Simmen D, Briner HR, Jones N: Objective Assessment of the nasolabial angle in rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2004; 6: 295-300

- Byrd HS, Andochick S, Copit S, Walton KG: Septal extension grafts: a method of controlling tip projection shape. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 100: 999-1010

- Kridel RWH, Foda HMT: Nasal Septal Perforation: Prevention, Management, and Repair. In: Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2nd edition. Ira D. Papel, Thieme Medical Publishers, NY 2002; Chapter 41: 473-481

- Schultz-Coulon H.J.: Experiences with the bridge-flap technique for the repair of large septal perforations. Rhinology 1994; 32: 25-33

- Becker DG, Bloom J: Five techniques I cannot live without in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 2008; 24: 358-364

- Vuyk HD, Zijlker TD: Nasal Dorsal Cyst after Rhinoplasty. Rhinology 1993; 31: 89-91

- Tardy ME Jr, Kron TK, Younger R, Key M: The Cartilaginous Pollybeak: Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Facial Plast Surg 1989; 6: 113-120

- Murakami CS, Larrabee WF Jr: Comparison of Osteotomy Techniques in the Treatment of Nasal Fractures.Facial Plast Surg 1992; 8: 209-219

- Sheen JH: Spreader Graft: A Method of Reconstructing the Roof of the Middle Nasal Vault Following Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery; 1984: 73: 230-239

- Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger M, Tardy ME Jr.: Use of Alar Batten Grafts for Correction of Nasal Valve Collapse. Arch Otolarnygol Head Neck Surg 1997; 123: 802-808

- Menger DJ: Lateral Crus Pull-up. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2006; 8: 333-337

- McCollough EG, Mangat D: Systematic Approach to Correction of the Nasal Tip in Rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 1981; 107: 12-6

- Adamson PA, Litner JA: Applications of the M-arch Model in Nasal Tip Refinement. Facial Plast Surg 2006; 22: 42-48

- Adamson PA, Funk E: Nasal tip dynamics. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2009; 17: 29-49

- Kridel RW, Scott BA, Foda HM: The Tongue-in-Groove Technique in Septorhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 1999; 1: 246-58

- Byrd HS, Andochick S, Copit S, Walton KG: Septal Extension Grafts: A Method of Controlling Tip Projection Shape. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 100: 999-1010