Introduction

In the modern era of rhinoplasty, the introduction of external rhinoplasty was greeted by enthusiastic advocates and also met with spirited opposition. Over time, however, the tenor of this debate has become more ecumenical. Most surgeons now recognize the broad utility of both endonasal and external approaches. Most understand that there are situations when a given approach offers advantages and may be considered preferable. Most also agree that there is a large “grey area,” where either the endonasal or the external approach would be appropriate, and the choice may be considered a “toss-up.” Most surgeons readily acknowledge that surgeon comfort with a procedure is an appropriately important factor.

In this chapter we will review the Anatomy, the Incisions and the Approaches that are available to the surgeon. We will discuss technical aspects of each approach. We will discuss general indications for the external approach and for the endonasal approaches. We will discuss the pros and cons of each approach, and provide further thoughts on the decision making process.

Anatomy, Incisions and Approaches

Nasal anatomy

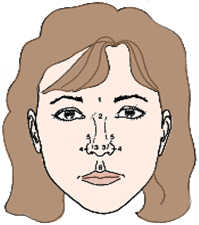

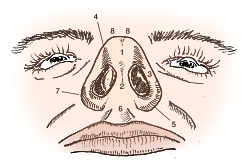

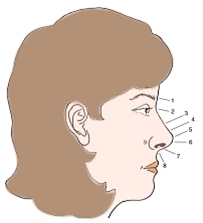

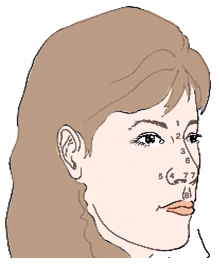

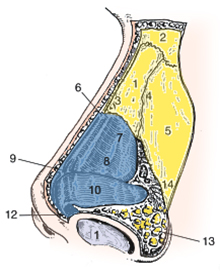

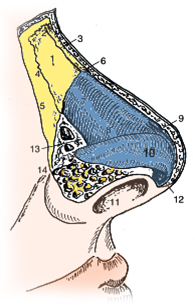

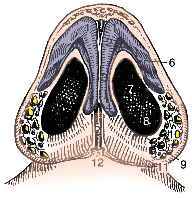

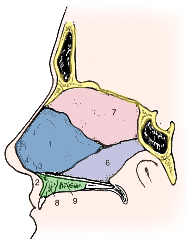

Although the anatomy of the nose has been fundamentally understood for many years, only relatively recently has there been an increased understanding of the long term effects of surgical changes upon the function and appearance of the nose. A detailed understanding of nasal anatomy is critical for successful rhinoplasty. This section reviews the surface and structural anatomy of the nose, with an emphasis on important surgical anatomy.

Accurate assessment of the anatomic variations presented by a patient allows the surgeon to develop a rational and realistic surgical plan. Furthermore, recognizing variant or aberrant anatomy is critical to preventing functional compromise or untoward aesthetic results. This section presents a limited diagrammatic overview of nasal anatomy (Figures 1-10). More detailed study of nasal and facial anatomy is recommended.1-3

| Figure 1: Frontal

1 – glabella |  |

| Figure 2: Base

1 – infratip lobule |  |

| Figure 3: Lateral

1 – glabella |  |

| Figure 4: Oblique

1 – glabella |  |

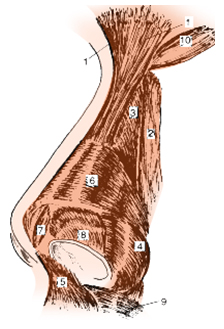

Figures 5-7 show the internal anatomy, beneath the skin.

| Figure 5: Oblique

1 – nasal bone |  |

| Figure 6: Lateral

1 – nasal bone |  |

| Figure 7: Base

1 – tip-defining point |  |

The septum is the midline structure inside your nose that divides the nose into left and right. The septum is an important structure in septorhinoplasty. Its anatomy is shown here.

| Figure 8: Septum

1 – quadrangular caratilage |  |

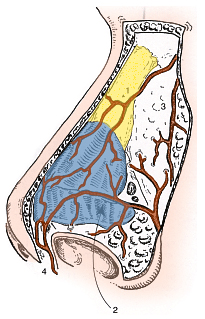

Figures 9-10 highlight the important fact that the skin over the nose has muscles and blood vessels. This may seem obvious, but it is important because the surgeon must fully recognize the importance of this fact. The surgeon must carefully avoid operating in the incorrect tissue planes, which can result in violation of the muscle and blood vessels and subsequent abnormal scarring.

| Figure 9: Musculature

A: Elevator muscles – B: Depressor muscles – C: Compressor muscles – D: Minor dilator muscles – E: Other – |  |

| Figure 10: Vasculature

1 – dorsal nasal artery |  |

Incisions and Approaches

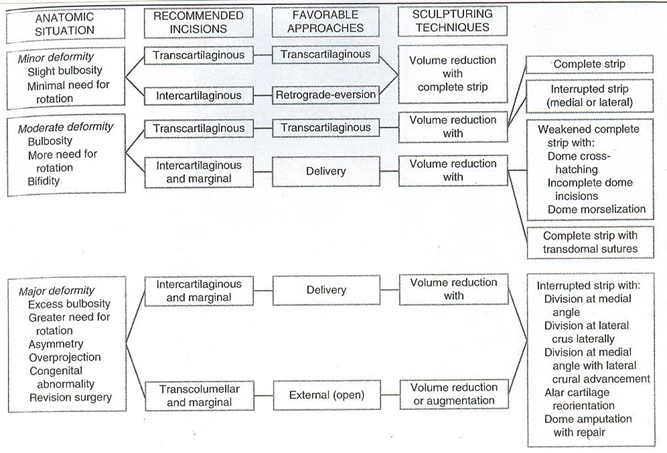

Incisions are methods of gaining access to the bony and cartilaginous structures of the nose, and include transcartilaginous, intercartilaginous, marginal, and trans-columellar incisions. Approaches provide surgical exposure of the nasal structures including the nasal tip and include cartilage-splitting (transcartilaginous incision), retrograde (intercartilaginous incision with retrograde dissection), delivery approach (intercartilaginous + marginal incisions), and external (transcolumellar and marginal incisions) (Table 1). Based on an analysis of the individual patient’s anatomy, appropriate incisions, approaches, and tip-sculpturing techniques may be selected.3-5

Table 1: TIP SUPPORT MECHANISMS, INCISIONS, & APPROACHES

Major tip support mechanisms

- size, shape, and strength of lower lateral cartilages

- medial crural footplate attachment to caudal septum

- attachment of caudal border of upper lateral cartilages to cephalic border of lower lateral cartilages

[Nasal septum is also considered a major support mechanism of the nose.]

Minor tip support mechanisms

1. ligamentous sling spanning the domes of the lower lateral cartilages (ie inter-domal ligament)

2. cartilaginous dorsal septum

3. sesamoid complex of lower lateral cartilages

4. attachment of lower lateral cartilages to overlying skin-soft tissue envelope

5. nasal spine

6. membranous septum

Incisions – methods of gaining access

Intercartilaginous

Trans-cartilaginous

Marginal (NOT to be confused with rim incision)

Trans-columellar

Approaches – provide surgical exposure

Cartilage-splitting

Retrograde

Delivery – Marginal + inter-cartilaginous incision

External approach – marginal + trans-columellar incision

Sculpting techniques – surgical modifications

Complete strip – ie cephalic resection, or volume reduction of lateral crura

Incomplete strip (Dome division)

Transdomal/Domal sutures

Augmentation grafting

Tip graft

Other

BASED ON THE ANATOMIC SITUATION, AN ALGORITHM OF RECOMMENDED INCISIONS, FAVORABLE APPROACHES AND SCULPTURING TECHNIQUES PRESENT A USEFUL STARTING POINT IN OPERATIVE PLANNING

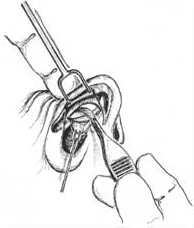

I. Trans-cartilaginous incision or cartilage-splitting approach – technical considerations

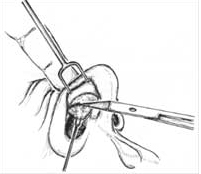

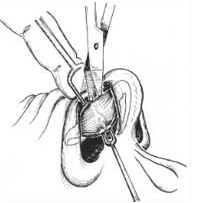

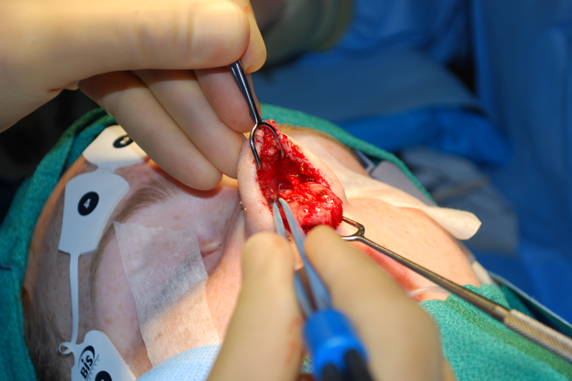

As demonstrated in the accompanying figures, use a two-prong retractor and the middle finger of the non-dominant hand to expose the lower lateral cartilage (LLC).

Locate the caudal and cephalic margins of the lateral crura. (The surgeon must identify the cephalically positioned lateral crus when it is present prior to executing this incision.) Make an incision through vestibular skin only 5 to 8 millimeters cephalic to the caudal margin of the lateral crus of the LLC incision. With scissors, dissect free the vestibular skin in a cephalic direction to just beyond the cephalic edge of the lateral crus (Figure 11).

Then, incise the lateral crural cartilage and free the cephalic portion (to be removed) from its remaining soft tissue attachments by dissecting superficially to it in the supra-perichondrial plane.

Use a skin hook to retract the caudal vestibular skin and another skin hook to retract the nostril margin. An assistant may hold the skin hook that retracts the nostril margin, while the surgeon grasps the cartilage to be removed and completes the excision by dividing any last soft tissue attachments with scissors (Figure 12). 3-5

II. Delivery approach – technical considerations

A. Intercartilaginous Incision

Using a two prong retractor, evert the caudal margin of the nostril and, by applying pressure with the middle finger of the non-dominant hand, present the gap between the caudal margin of the upper lateral and the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilages. With a scalpel, make an inter-cartilaginous incision in this location (Figure 13). 3-5

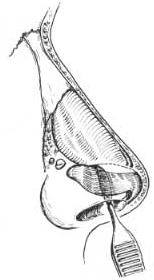

B. Marginal Incision

Using a two prong retractor, evert the caudal margin and, by applying pressure with the middle finger of the non-dominant hand, define the caudal margin of the lower lateral cartilage. Pressing cephalad on the nasal dome will cause the caudal margin to present itself laterally. Remember that the non hair-bearing area is a guide to the caudal margin of the lateral crus. Furthermore, palpation of the cartilage edge with the handle of the scalpel can be helpful before cutting. Using the two prong retractor to obtain proper exposure, make the marginal incision just caudal to the caudal edge of the lower lateral cartilage (Figure 14).

Great care must be taken as the lateral incision nears the midline. Make sure that the incision follows the cartilage edge and does not take a “short-cut” along the alar rim, which can damage the facet area. Great care must be taken not to cut across a narrow dome or intermediate crus. 3-5

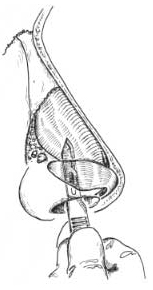

C. Delivery of lower lateral cartilages

Re-insert the two prong retractor into the nostril with the intercartilaginous and marginal incisions and re-present the caudal margin of the lower lateral cartilage with the aid of pressure from the third finger of the non-dominant hand.

Use a slightly-curved, fine-pointed dissecting scissors to lift and dissect the soft tissues from the surface of the lower lateral cartilage (Figure 15).

Perform this dissection by inserting scissors into the marginal incision laterally, and then separate the perichondrium of the lower lateral from the overlying external skin and soft tissue with a spreading motion. If this is difficult, caudal traction on the vestibular skin underlying the lower lateral cartilage, with a fine two prong hook, will facilitate this maneuver (Figure 16)

by pulling the lateral crus into the vestibule and thus opening up the potential dissecting plane. Avoid damaging the overlying muscle and nasal vasculature.3-5

Do not work too far laterally. The lateral one quarter of the lower lateral cartilage should be avoided by the surgeon in nearly all cases.

Place the hook end of a Nievert (or other similar) retractor through the inter-cartilaginous incision and draw the now-free lateral crus down, like a visor, until it presents outside of the vestibule. It can be held in this position by the Nievert, or by another suitable instrument. Examine the lower lateral cartilages for unique anatomical features and asymmetries(Figure 17).

III. The external (open) rhinoplasty approach

Background

The external rhinoplasty approach to the nose provides maximal exposure of the lower lateral cartilages, upper lateral cartilages, middle nasal vault, and bony nasal vault. 3,6-13 The incisions used in this approach include a transcolumellar incision connected to bilateral marginal incisions. The actual configuration of the transcolumellar incision is not as critical as the placement of the incision. The incision should be made at the level of the midcolumella where the caudal margins of the medial crura lie close to the skin and can support the incision to help prevent a depressed scar. An inverted -V incision, or some other “broken-line” incision, is used to break up the scar and lengthen it to minimize scar contracture. The surgical dissection must be performed in the proper areolar tissue planes to minimize tissue damage and scarring, maintain hemostasis and maximize redraping of the skin-soft tissue envelope. Dissection in proper tissue planes will help preserve vascular structures of the flap, insure flap viability, and minimize bleeding, postoperative edema, and scarring.2

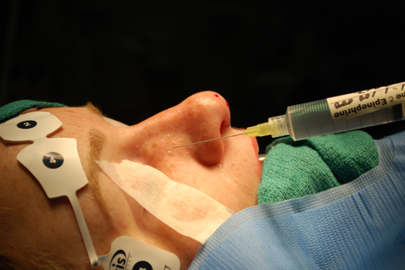

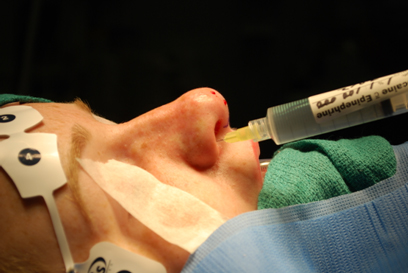

A. Marking the trans-columellar incision. Injecting the nose.

Begin by outlining the transcolumellar incision used in the external rhinoplasty approach with a marking pen. Mark an inverted-V transcolumellar incision at the level of the midcolumella. The midcolumellar incision should be marked midway between the top of the nostril and the base of the columella, where the caudal margin of the medial crura lie just beneath the skin to provide support for the incision. The midcolumellar incision will be connected to bilateral marginal incisions which are placed just caudal to the caudal margin of the lateral crura. The marginal incision should not be made along the rim of the nostril (rim incision). The marginal incision may be marked with a marking pen as well.

After making appropriate markings on the nose, local infiltrative anesthesia (1% lidocaine with 1/100,000 epinephrine) is applied. The technique of the author is described in another chapter of this textbook, and is also illustrated below (Figure 18). No more than a few milliliters of local are injected. Later in the operation, a small additional amount of local infiltrative anesthesia may be applied.

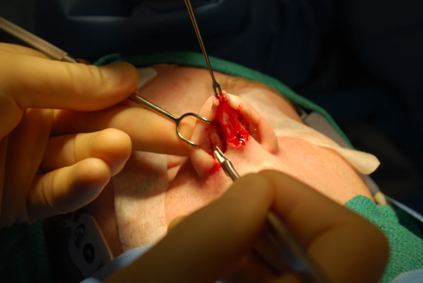

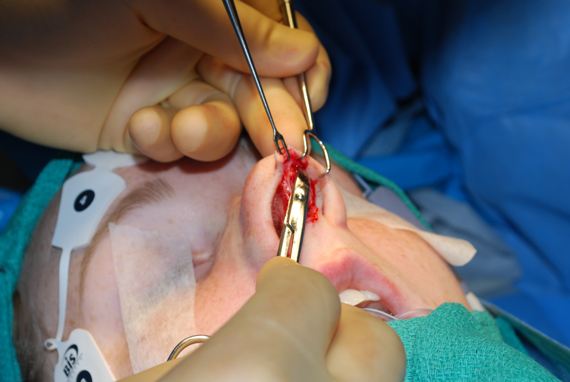

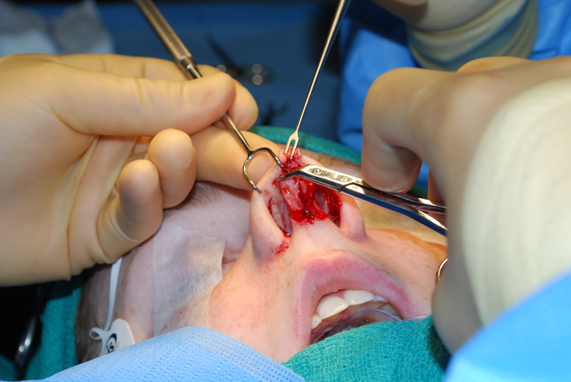

FIGURE 18: Mid-columellar incision is shown here. Local infiltrative anesthesia (1% lidocaine with 1/100,000 epinephrine) is also illustrated.

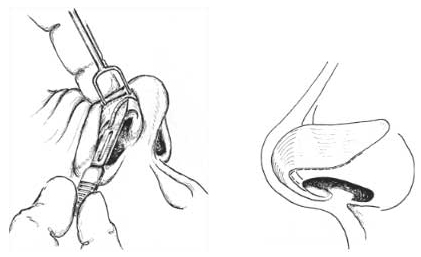

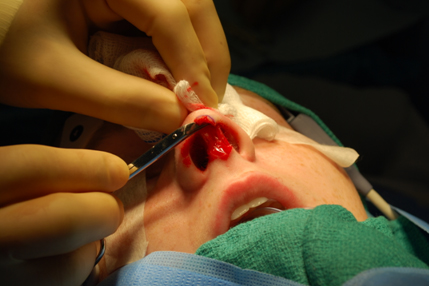

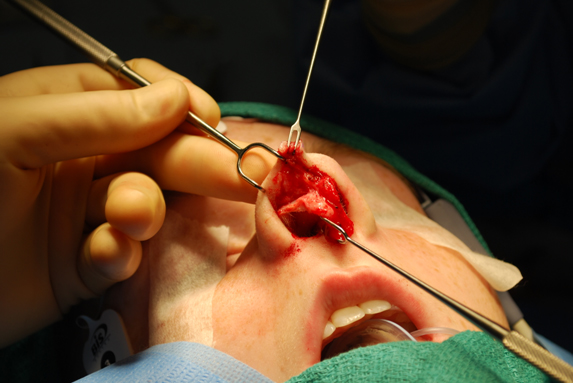

B. Midcolumellar incision.

Using an 11 blade with a “sawing motion,” follow the mid-columellar markings to complete the midcolumellar incision. Proceed medial to lateral on one side of the columella, and then the other. Take special care to keep the blade perpendicular to the skin edges, thereby preventing bevelling of the skin edges. (Bevelling of the skin edges may lead to a “trapdoor” deformity with eventual unacceptable scar). As one incises laterally, be careful to stay superficial to avoid damage to the caudal margin of the medial crura. (Figure 19)

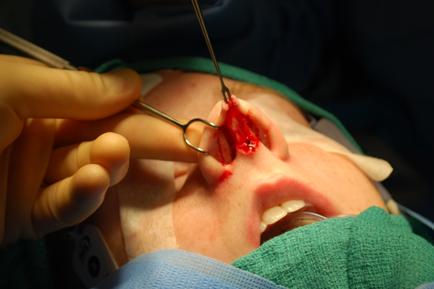

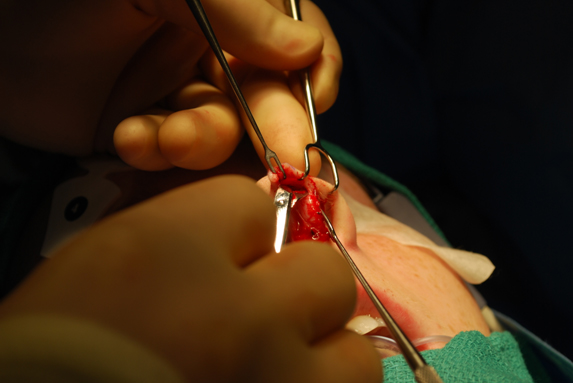

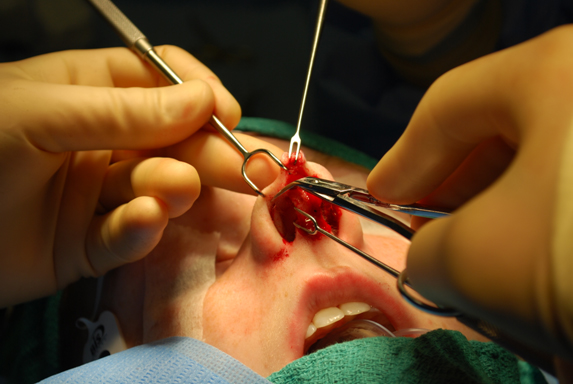

Use a 15 blade to make the columellar extension of the marginal incision on both sides of the columella, 1 to 2mm behind the leading edge of the columella (Figure 20). This incision is made along the caudal margin of the medial and intermediate crura. By minimizing the dissection over the medial crus, damage to this cartilage can be avoided.

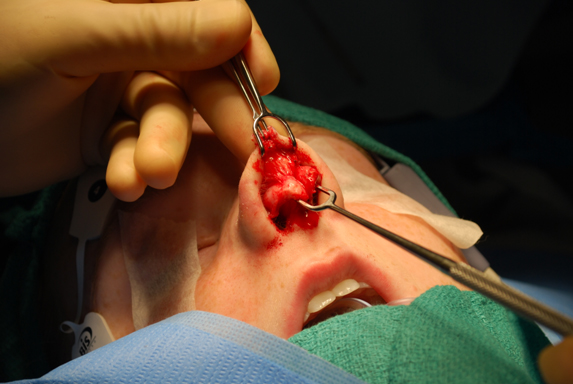

C. Define the columellar flap.

Using angled Converse scissors, or another suitable dissecting scissors, elevate the thin vestibular skin of the flap that covers the medial crura. Insert the scissors beneath the columellar extension of the marginal incision and dissect medially in the correct plane of dissection, below the musculoaponeurotic layer. (Figure 21)

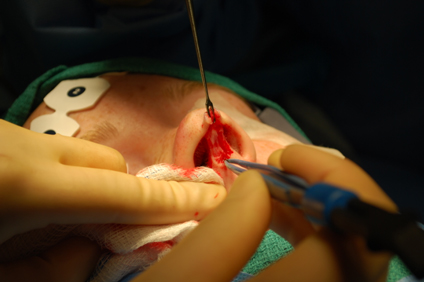

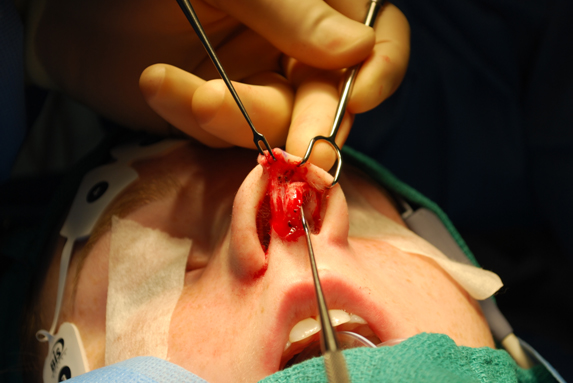

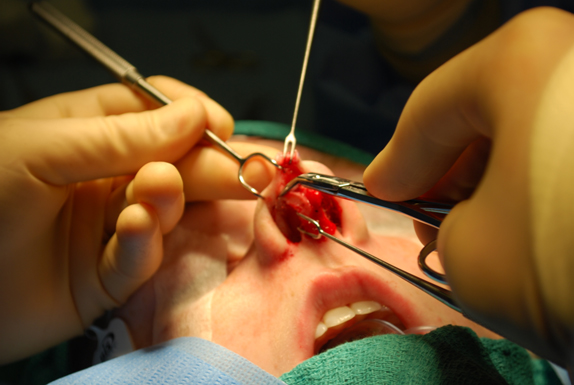

Repeat this maneuver on the opposite side. The scissors should then pass superficial to the caudal margin of the ipsilateral and then contralateral medial crus. Guide the scissors through the opposing columellar extension of the marginal incision. During this dissection, take special care to avoid damaging the flap. Use the scissors to spread the tissues in the plane of dissection. (Figure 22)

Use the Converse scissors to complete the mid-columellar incision without bevelling the incision or damaging the medial crura. Take special care to avoid bevelling this incision. (Figure 23)

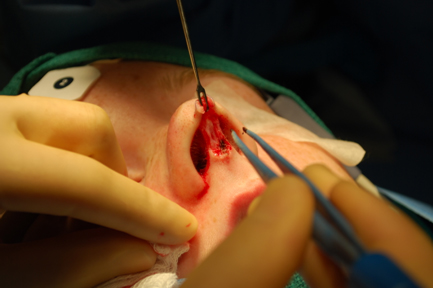

D. Marginal incision.

Beginning laterally, make a light incision through vestibular skin 1 to 2 mm caudal to the caudal margin of the lateral crura. Follow the caudal margin of the lateral crura as you extend the incision medially. (Figure 24)

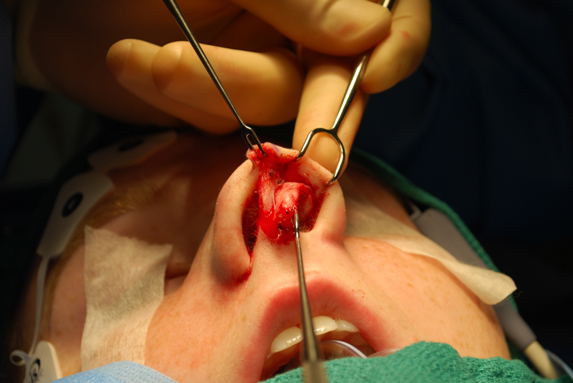

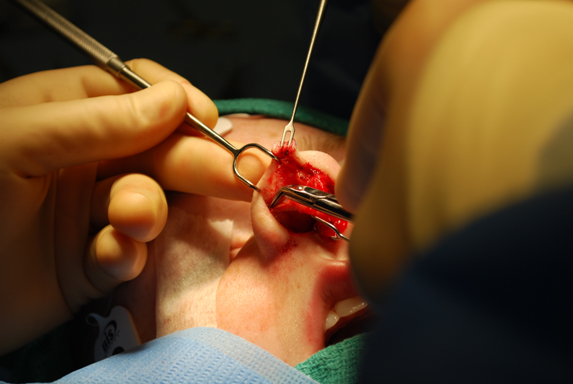

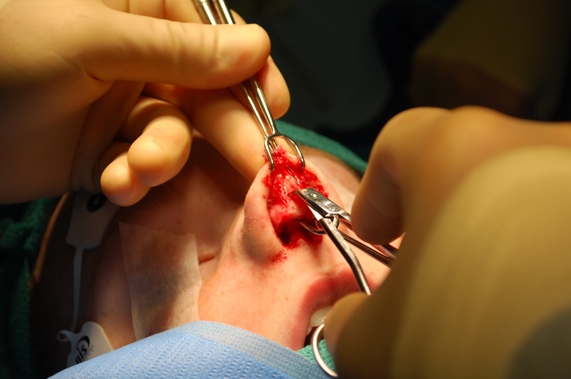

E. Bipolar the paired columellar arteries.

Use a narrow double prong hook to retract the flap. The paired columellar arteries typically need to be cauterized with bipolar cautery. (Figure 25)

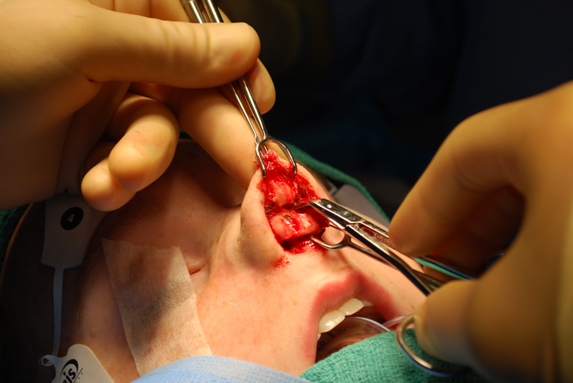

E. Flap Elevation – three-point countertraction. (Figure 26)

To elevate the skin soft tissue envelope over the nasal tip, 1) place a wide double prong hook along the margin of the nostril rim caudal to the lateral crus, 2) place a small double prong hook on the columellar flap, and 3) place a small double prong hook on the vestibular skin side of the intermediate crus (Figure 26, above). Then, use Converse scissors to dissect the columellar flap from the caudal margin of the medial and intermediate crus as the counter-traction acts to expose the areolar tissue plane. The scissors are used to expose the caudal aspect of the lateral crus as well. Then, the dissection advances cephalically over the surface of the lateral crus. As the dissection continues along the surface of the lateral crus, soft tissue is elevated leaving only perichondrium on the cartilage. As dissection proceeds laterally along the lateral crus, cut the vestibular skin along the caudal margin of the lateral crus, thereby completing the marginal incision. Make small, calibrated cuts under direct vision to avoid inadvertently cutting through the lateral crus. Limit dissection of the lateral crus to the areolar tissue plane deep to the muscle. A cotton tip applicator can be used to complete the dissection of the lateral crus once the deep aerolar tissue plane has been identified. A portion of the dissection on the opposite side was performed when you undertook the cartilage delivery approach; nevertheless, repeat these maneuvers on the opposite side to complete elevation of the skin-soft tissue envelope over the nasal tip.

Retrograde approach

An alternative approach to this dissection is to begin dissection through the marginal incisions (retrograde dissection).14 In this approach, identify the proper tissue plane and elevate the skin-soft tissue envelope off of the lateral crus. Then proceed medially with scissor dissection toward the domes and intermediate crura. This maneuver is performed bilaterally to achieve elevation of the skin-soft tissue envelope.

Retrograde dissection is helpful in cases where the surgeon is having difficulty following the caudal margin of the intermediate and lateral crus. This is not unusual in cases where there is buckling of the intermediate crus or domes. Retrograde dissection may not be the approach of choice for secondary rhinoplasty when the lateral crura has been excised or previously resected. However, the retrograde approach can be extremely helpful in secondary rhinoplasty cases in which the primary surgery was performed via an external approach, when the medial crura dissection is hindered by excessive scarring.

G. Midline dorsal dissection. (Figure 27)

Divide fibrous connections in the midline near the surface of the domes to release the flap and allow dissection cranially. Do not dissect tissue from between the domes; otherwise a midline band of tissue may be left on the flap. Shift the dissection to the midline where the anterior septal angle is identified with a spreading action of the Converse scissors or other suitable dissecting scissors. Once the blue hue of the cartilaginous middle-third of the nose has been identified, create a midline tunnel over the cartilaginous middle vault. Then use a cotton tip applicator to bluntly dissect the soft-tissue envelope cranially and laterally (Figure 27, above). This maneuver will frequently expose sizable blood vessels that can be spared as they are dissected laterally. Depending on the degree of exposure that is needed, some fibrous connections may need to be cut near their attachment to the cartilaginous nasal vault. Muscle and vessels can be spared by dividing tissues close to the surface of the cartilages.

H. Closure of columellar incision

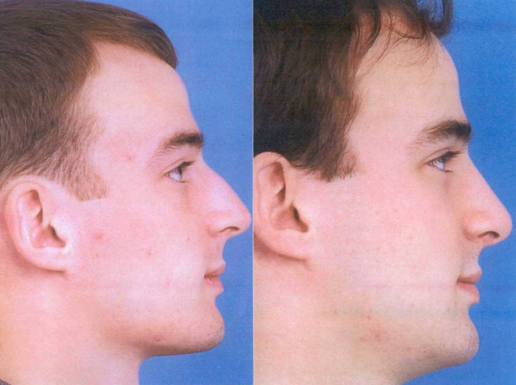

For the transcollumellar incision, it is important to have a tension free closure. (Figure 28, below) Consider using a deep suture if there is any tension. Evert skin edges, pay meticulous attention to proper skin edge alignment, and be careful to avoid notching. Be careful not to BEVEL the incision to avoid a “trap-door” abnormality.

Figure 28 – Before and after external rhinoplasty. Tension-free closure improves final scar appearance.

DISCUSSION:

Indications for Endonasal versus External, and Pros and Cons of each

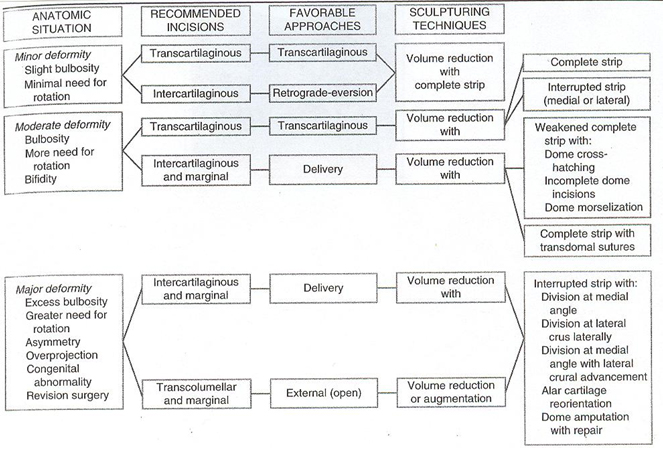

An operative algorithm often provides a helpful starting point in selecting the incisions, approaches and techniques used in nasal tip surgery (Table 2). In every case, the patient’s anatomy directs the selection of appropriate technique. As the anatomic deformity becomes more abnormal, a graduated, stepwise approach is taken. However, other factors, such as the need for spreader grafts, complex nasal deviation, surgeon preference, and other factors may also appropriately affect the ultimate selection of approach.5

Table 2. Based on the anatomic situation, an algorithm of recommended incisions, favorable approaches, and sculpturing techniques present a useful starting point in operative planning.

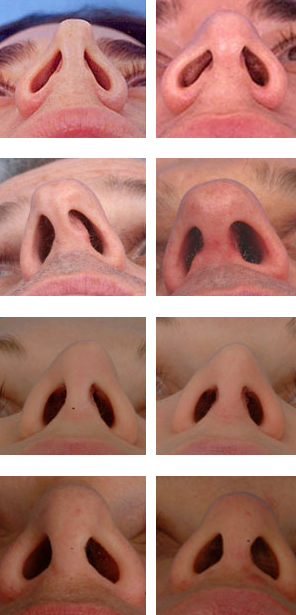

The endonasal approach may be generally preferred for patients requiring conservative profile reduction, conservative tip modification, selected revision rhinoplasty patients, and other situations in which conservative changes are being undertaken (Figure 29).

Figure 29: In a patient with relatively conservative changes are being undertaken, the endonasal approach may be advantageous, as in this patient seeking only conservative profile reduction.

Advantages of less invasive approaches include less dissection, less edema, less “healing.” However, less invasive approaches provide by their very nature less exposure, which in some cases may be a disadvantage.

Indications for external rhinoplasty approach3,6,7,9 (Table 3) generally include asymmetric nasal tip, crooked nose deformity (lower two thirds of nose), saddle nose deformity, cleft-lip nasal deformity, secondary rhinoplasty requiring complex structural grafting, and septal perforation repair. Other indications may include complex nasal tip deformity, middle nasal vault deformity, Selected nasal tumors. Some surgeons prefer the open approach for less complex nasal tip deformities due to the precision that they feel it offers them, in their hands, compared to the endonasal approach.

Table 3: Indications for External Rhinoplasty Approach

Asymmetric nasal tip

Crooked nose deformity (lower two thirds of nose)

Saddle nose deformity

Cleft-lip nasal deformity

Secondary rhinoplasty requiring complex structural grafting

Septal perforation repair

Advantages of the external approach include the maximal surgical exposure available, potentially allowing more accurate anatomic diagnosis. The external approach also provides the opportunity for precise tissue manipulation, suturing and grafting. Disadvantages include the transcolumellar incision, wide field dissection resulting in loss of support, nasal tip edema.

Regardless of approach, one must be mindful of the need to maintain appropriate structural support. When the approach is disruptive of tip support, counter measures, such as the placement of a columellar strut, are warranted. When the support to the upper lateral cartilages has been disrupted, spreader grafts may be appropriate.

External and Endonasal Approaches to the Upper Third

The bony pyramid can be reliably reduced, repositioned or augmented through a closed approach. However, Larrabee reports that open rhinoplasty may allow more precise refining of its contour.15 Larrabee reports that the incidence of profile irregularities may be reduced when procedures are performed via the open approach.

Larrabee points out that while there is a tendency to treat the bony pyramid in an essentially closed fashion when using the open approach, the benefits of increased exposure to the dorsum available with the open rhinoplasty approach should be exploited whenever possible.

In my experience, a closed approach has been reliable for addressing most bony profile problems. However, when I perform an open rhinoplasty, at times I will undertake hump reduction under direct visualization. When using an osteotome, I use an 8mm non-guarded osteotome. (Wider osteotomes can create an injury to the skin-soft tissue envelope.) When rasping during open rhinoplasty, I employ a powered rasp under direct visualization.16

External and Endonasal Approaches to the Middle Nasal Vault

The determination of the need for spreader grafts may play a significant role in determining whether open approach will be used, even when the tip could be satisfactorily addressed by endonasal approaches. Modern rhinoplasty techniques increasingly emphasize preservation of cartilaginous and bony substructure. This is of particular importance in the middle nasal vault, as preservation of support for the upper lateral cartilages helps to avoid collapse of the middle vault and the associated internal nasal valve. Middle vault and nasal valve collapse can cause overnarrowing of the middle third of the nose, with the “inverted V” deformity and nasal obstruction. When support and contour of the middle vault require reconstitution, spreader grafts can be used.

Use of spreader grafts in primary rhinoplasty is becoming much more common.10, 17-18 Spreader grafts can be effective in maintaining the contour of the middle vaults after hump reduction. While it may be technically easier to place spreader grafts via an external approach, spreader grafts can be placed via the endonasal or the external(open) approach.6,9-10,19-20

Narrowing of the middle nasal vault that occurs when the T configuration of the nasal septum is resected with dorsal hump removal may be problematic in the high risk patient.10 Spreader grafts act as a spacer between the upper lateral cartilage and septum, preventing excessive narrowing in the high risk patient or correcting an over-narrow middle vault when it exists.

As described by Sheen19, a submucoperichondrial tunnel on one or both sides of the dorsal aspect of the septum may be prepared by elevating the mucoperichondrium bridging the upper lateral cartilages to the septum. This dissection provides a space to be filled by a cartilage strip insinuated and secured by suture-fixation into the pocket, lateralizing the upper lateral cartilage(s), improving the airway and effectively maintaining the width, or widening when indicated, the appearance of the middle third of the nose. Spreader grafts are well-addressed and well-illustrated in other chapters in this textbook.

Spreader grafts may be comfortably carried out through traditional, less invasive endonasal techniques. In more complex reconstructions, particularly complicated by multiple abnormalities, an external rhinoplasty approach may facilitate accurate dissection and graft suture fixation. Some surgeons find that the external approach is simply a technically easier method to undertake spreader graft placement.

It should be noted that the use of the external rhinoplasty approach may lead to a greater need for spreader grafts to preserve the nasal valve and middle nasal width, which may put at risk due to the loss of support to the upper lateral cartilages caused by more extensive skin undermining.

Identifying the high risk patient during initial preoperative analysis is essential to the prevention of excessive narrowing of the middle nasal vault with internal nasal valve collapse.10 Sheen19 identified an anatomical variant that he labelled the “narrow nose syndrome.” Short nasal bones, long weak upper lateral cartilages, thin skin, and a narrow projecting nose predispose to middle vault collapse.9-10 As described by Toriumi10, commonly performed surgical maneuvers can result in loss of support to the middle vault. A large en bloc hump removal should be avoided, as the T-shaped support of the nasal septum is eliminated and the intranasal mucosa (which provides important support to the upper lateral cartilage) is at risk of injury. Cephalic trim (volume reduction) of the lateral crura disrupts the scroll (recurvature) and frees the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage. Lateral osteotomies may further medialize the upper lateral cartilages. The upper lateral cartilages can fall toward the narrowed dorsal septal edge, producing middle vault and internal valvular collapse.10 Collapse of the middle vault may highlight the caudal edges of the nasal bones to produce the characteristic “inverted V” deformity.10,19

In the majority of patients the combination of these maneuvers will not result in a problem; however, in high risk patients this combination of maneuvers may contribute to excessive narrowing of the middle vault with internal valve collapse.

Experience is required to develop reliable surgical judgment regarding the appropriate use of spreader grafts. After spreader grafts are secured in position via the open approach, or if they are placed endonasally after dissection of the soft tissue envelope, the middle vault may appear slightly wide. Over time, this area of the nose tends to narrow as edema resolves and scar contracture pulls the upper lateral cartilages medially.10

External and Endonasal Approaches to the Nasal tip

Complex nasal tip procedures can be performed via endonasal and external approaches. Certain grafting techniques such as lateral crural strut grafts, and certain manipulations of the tip cartilages such as lateral crural overlay and intermediate crural overlay, and “tongue-in-groove” retrodisplacement of the medial crura onto the caudal septum, may be performed via either approach, but certainly the exposure afforded by the open approach may be preferable (Figure 30).21-24

Figure 30: This patient had a significant caudal septal deviation and severe concavity of the right lateral crus. Correction of the tip deformity required excision and “flipping” of the right lateral crus. While this can be performed using an external or a delivery approach, the surgeon found that the exposure afforded by the external approach was preferable.

External and Endonasal Approaches to Revision Rhinoplasty

In revision surgery, once the nose is open, any supportive relationships that exist between the scar tissue and underlying structure is lost, and cartilage grafting may be required to support and contour the skin/soft tissue envelope that will now undergo renewed scar contracture and healing. If not, healing and scar contracture may leave a worse deficit than before. Therefore, in revision cases with relatively mild deformities or those that can be corrected with precise pocket grafting, closed approach is preferred. The surgeon should seek an endonasal approach, but may find that in complex cases an open approach is unavoidable. Spreader grafts, batten grafts, onlay grafts are examples of maneuvers that can be well-placed via precise pocket, endonasal techniques (Figure 31).25

Figure 31: This patient required a triple layer onlay graft to address her saddle nose abnormality. This graft was well-placed via a precise pocket, endonasal approach.

Endonasal and external approaches to the deviated caudal and dorsal septum

For severe caudal septal deviation, the open approach may provide a more facile and efficacious approach, when swinging door, doorstop and other similar maneuvers have failed.26-27 Although many techniques to address a severe caudal deviation can be done open or closed, it is an issue of balancing the downsides of a technique against the increased chance of achieving the technique as desired. To some extent, this is ultimately a personal judgment, guided by critical self-evaluation.

Philosophical Considerations – A Graduated Approach. The Big Picture

When considering the decision-making around the choice of approach, much can be gained by considering the experiences of surgeons who have had the opportunity to see the consequences over time of the choices they have made.

The important philosophical concept is not open or closed, but instead, the emphasis on anatomic diagnosis and preservation of supportive structures.

A central tenet of rhinoplasty decision-making has been the concept of a graduated approach. This concept is based on the idea that achieving the desired goals with the least amount of surgical dissection provides the best chance of success. However, the critical issue here is how much exposure is needed for reliable execution of any specific technical maneuver.

Adamson28 has astutely observed that there is no ideal approach, each surgeon will develop a unique approach based upon the concepts outlined and based on the techniques and experiences he or she has developed in the course of an eclectic training. The skillful surgeon can make astute intraoperative anatomic diagnosis via the endonasal or external approach. Notwithstanding this, an important factor that can compromise results is the potential difficulty in diagnosis of various deformities and abnormalities using closed approaches, Another factor is the manual difficulty in correcting such deformities once diagnosed, especially effecting such maneuvers as vertical cartilage division, graft placement, and suturing techniques. Those trained in the closed approach will still tend to perform the majority of their rhinoplasties in this fashion, reserving the open approach for more difficult noses. This assessment will vary from surgeon to surgeon (Figure 32).

Figure 32: While some surgeons may choose address this revision rhinoplasty via a closed approach, the author felt that, in his hands, the exposure obtained from the external approach offered the best opportunity for successful correction of the tip deformity.

Perkins29 describes an evolution in his personal philosophy that reflects some of the issues involved in the decision making process, and provides valuable insight into the evolution in the decision making that has occurred over the last 15-20 years. While the concept of a graduated approach to achieve a pleasing aesthetic result has been foremost in his personal philosophy, the evolving need to achieve more refined results and prevent late complications has resulted in his increased use of the open approach, which allows the opportunity to use certain grafting techniques. Perkins continues to strongly advocate the philosophy that the approach selected should provide the least intervention in the shortest time to achieve a satisfactory result and satisfy the patient’s goals. However, his choice of approach has changed due to late complications that he has seen occur. The 2 areas that he found most commonly cause late complications in rhinoplasty are the midnasal pyramid and lateral alar sidewalls. Paramount to provide a structural foundation for the middle vault (ie spreader grafts). While issues such as these can be addressed using the endonasal approach, it is sometimes far easier to place structural grafts via the external approach. Also, when marked reduction of overprojection is required, it is often easier to use the external columellar approach.

Although I was asked to write a chapter on “Open Versus Closed Rhinoplasty,.” I have instead written a chapter on “Open And Closed Rhinoplasty.” While this may seem like a semantic point, I believe that the surgeon should understand the advantages offered by every surgical approach. The concepts of minimizing dissection, born from endonasal techniques, also apply to external rhinoplasty. Every surgeon should be able to “think like an endonasal surgeon” – that is, to understand the advantages of limiting the surgical dissection. But, one should also be able to recognize when the additional exposure offered by the external approach may be useful and even necessary. When the external approach is undertaken, the surgeon must understand the commitment that has been made to additional support maneuvers.

There is no single answer to the question, “open versus closed rhinoplasty.” In each patient, diligent attention must be paid to the patient’s goals and to the patient’s anatomy. The wise surgeon includes external and endonasal rhinoplasty as choices in his or her armamentarium, and understands the critical issues of maintaining or adding structural support for improving long-term outcomes. The choice for a specific patient will ultimately depend upon the surgeon’s personal opinion as to which approach, in their hands, will provide the best chance of long-term success with the least amount of surgical dissection.

References

1. Tardy ME. Brown R. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose. Raven Press 1990.

2. Toriumi DM, Mueller RA, Grosch T, Bhattacharyya TK, Larrabee WF. Vascular Anatomy of the Nose and the External Rhinoplasty Approach. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 122: 24-34, January 1996.

3. Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA 1999.

4. Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Philosophy and Principles of Rhinoplasty. Chapter 31 in Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, 2nd edition (ed. Cummings et al) Mosby Year Book, pp 278-294.

5. Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, 1997.

6. Johnson CM Jr, Toriumi DM. Open Structure Rhinoplasty. Philadelphia, PA, Saunders, 1990.

7. Adamson PA. Open Rhinoplasty. In ID Papel & NE Nachlas (eds) Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery (pp 295-304) St Louis: Mosby Year Book, 1992.

8. Larrabee WF, Jr. Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Plastic Clin N Amer 1(1):23-38, 1993.

9. Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Open Structure Rhinoplasty – Featured Technical Points and Long-Term Follow-Up. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1): 1-22, August 1993.

10. Toriumi DM. Management of the Middle Nasal Vault. Operative Techniques in Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2(1):16-30, February 1995.

11. Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative Surgical Management of the Crooked Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1): 63-78, August 1993.

12. Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Management of the Lower Third of the Nose – Open Structure Rhinoplasty Technique. Chapter 33 in Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery (ed Papel and Nachlas), pp 305-313.

13.Gunter JP. The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 99(3): 863-867, 1997.

14. Thomas JR. External rhinoplasty:intact columellar approach. Laryngoscope 100(2 Pt 1):206-208, 1990.

15 Larrabee WF. Open Rhinoplasty and the Upper Third of the Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1):1993, 23-38.

16 Becker DG. The Powered Rasp, Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 2001.

17. Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The Relative Importance of Septal and Nasal Valvular Surgery in Correcting Airway Obstruction in Primary and Secondary Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

18. Teichgraeber JF, Wainwright DJ. The Treatment of Nasal Valve Obstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery93(6):1174- 1184, 1994.

19. Sheen JH. Spreader Graft: A Method of Reconstructing the Roof of the Middle Nasal Vault Following Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 73(2):1984, 230-237.

20. Aiach G. Atlas de Rhinoplastie, Paris, France, Masson, 1989, pp 74-85.

21. Soliemanzadeh P, Kridel RWH. Nasal tip overprojection: algorithm of surgical deprojection techniquesand introductionto medial crural overlay. Arch Facial Plastic Surg 2005;7:374-380.

22. Konior RJ, Kridel RWH. Controlled nasal tip postioning via the Open Rhinoplasty Approach. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993: 53-62.

23. Adamson PA. Nasal Tip Surgery in Open Rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1):1193, 39-52.

24. Wise, JB, Becker SS, Sparano A, Steiger J, Becker DG. Intermediate Crural Overlay in Rhinoplasty: A Deprojection Technique that Shortens the Medial Leg of the Tripod without Lengthening the Nose. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. Vol 8:240-244, 2006.

25. Perkins SW, Tardy ME. External Columellar Incisional Approach to Revision of the Lower Third of the Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, pp 79-98.

26. Pastorek NJ, Becker DG. Treating the Caudal Septal Deflection. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 2: 217-220, 2000.

27. Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative Surgical Management of the Crooked Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, 63-78.

28. Adamson PA. Nasal Tip Surgery in Open Rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, 39-52.

29. Perkins SW. The evolution of the combined use of endonasal and external columellar approaches to rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 12(2004):35-