Introduction

Rhinoplasty is one of the most popular cosmetic surgeries performed in Asian countries. Although the techniques employed may be considered similar to Caucasian rhinoplasty, the procedures used for Asians have distinctions which stem from their anatomical differences as well as different aesthetic standards between the two cultures.1-3

With the increasing number of rhinoplasties being performed coupled with heightened patient expectations, the rate of revision surgery is increasing in Europe and North America.4,5. Although no formal studies have been done on the rate of revision rhinoplasties in Asian countries, the author imagines that similar trends dominate. As primary rhinoplasty among Asians includes peculiarities that distinguish the procedure from its Caucasian counterpart, instinct dictates that revision rhinoplasty among Asians occupies a distinct field in the world of rhinoplasty that poses special and unique challenges to the rhinoplasty surgeon. However, reports of revision rhinoplasties among Asians are limited in their number and content.6,7

In Asians, augmentation of the dorsum or tip is the most commonly performed procedure. Although the preferred implant material is autologous cartilage, the characteristics of the Asian nose, which includes a broad and low dorsum that usually requires substantial augmentation, exceed the amounts available from autologous cartilage. This realistic limitation has popularized the use of alloplastic implants in many Asian countries. Among various alloplastic materials, silicone in its various forms has been and remains the single most commonly used alloplastic implant in Asia.9-10 This is perhaps because they are better tolerated due to the thicker soft tissue envelope of the Oriental nose.11 However, silicone implants have also been heavily criticized for their association with complications, such as deviation, extrusion, and infection.12 The complication rate of allopastic implants used in rhinoplasty ranges from 0 to 9.7% for silicone11,13and 1.5 to 10% for Goretex.14-16 A recent meta-analysis on alloplastic implant use in rhinoplasty showed a 3.1% removal rate for both Gore-Tex and Medpor implants and a significantly higher rate of 6.5% for silicone implants.17

In this short review of revision rhinoplasty in Asian, the author introduces the common causes of revision rhinoplasty, operative techniques and general considerations for each deformity, and implications to assist in their prevention.

Common etiologies

Most of the revisions in Asian rhinoplasty is associated with alloplastic implant related problems. Deviation, extrusion, foreign body reaction, or infection of the implant is a common problem. The major reasons for revision in the alloplast unrelated caese are dorsa and tip problems which include dorsal deviation or irregularity, residual hump, inadequate or loss of tip projection, upturned or over-rotated tip, visible graft, and tip deviation.

A retrospective review of my 623 cases of rhinoplasty between 2005 and 2008 revealed a 68 revision rhinoplasties.18Among them, 52 patients who had complete medical records and a follow up of at least one year were analyzed and the etiologies are shown in the table below.

Main etiology for revision rhinoplasty (N=52) |

|

|---|---|

| Alloplast related (N = 33) | 33 (63%) |

| Deviation | 12 |

| Foreign body | 5 |

| Extrusion | 5 |

| Infection | 4 |

| Unnatural look | 4 |

| Contracture (Short nose) | 3 |

| Alloplast unrelated (N= 19) | 19 |

| Mainly upper two-thirds problem | (N= 12) |

| Residual deviation | (37 %) |

| Dorsal irregularity or depression | 7 |

| Residual hump | 4 |

| Mainly tip problem | (N= 7) |

| Tip underprojection (loss of projection) | 12 |

| Upturned, overrotated tip | 2 |

| Visible graft | 2 |

| Tip deviation | 1 |

| Nasal obstruction | 4 |

Operative techniques and general considerations

Open rhinoplasty with use of autologous cartilage is the mainstream approach for most of the revisions. In patients with depleted cartilage, autologous or homologous rib cartilage provides an ample supply of materials. Perichondrium of the rib, temporalis fascia, or homologous fascia is used in patients with thin or traumatized skin.

The techniques used for revision rhinoplasty varies according to the etiology of the revision. In the implant related group, these are treated first by removal of the implant through an open approach, correction of underlying deviation if present, symmetric dissection and creation of a new subperiosteal pocket, and further augmentation of the dorsum or tip as needed. In cases with infection of the alloplastic implant, removal of the implant and revision surgery is performed concurrently using autologous grafting material.

For the revision of non-implant related patients, diverse techniques are used that include septal reconstruction, osteotomy, onlay and camouflage grafts, and various tip grafts used to control rotation and projection of the tip. Combined complaints of nasal obstruction are due to inadequate correction of septal deviation and turbinate problems. Proper management of the septum combined with conservative submucosal resection of the inferior turbinate is sufficient in maintaining patent nasal airways.

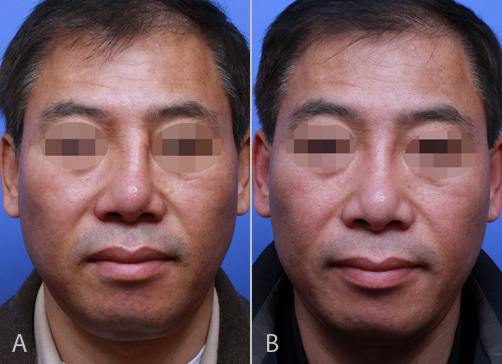

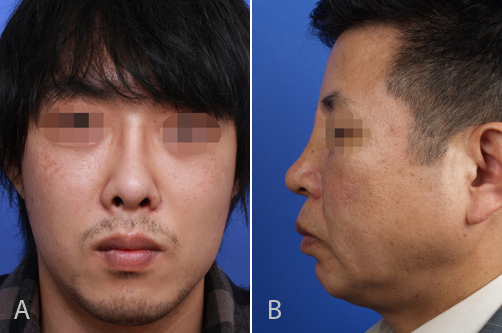

Deviation of implant

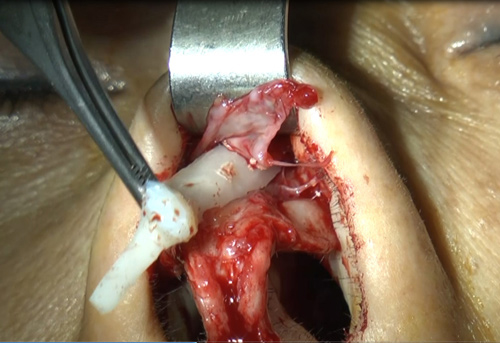

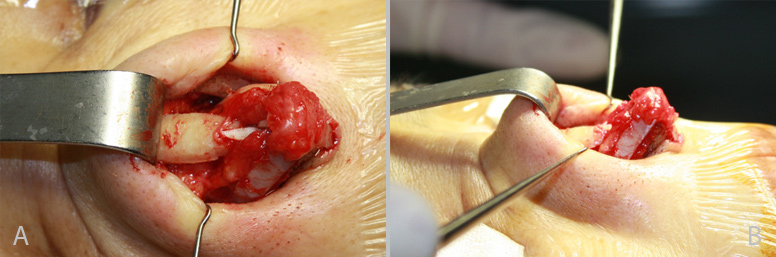

Deviation is the most common alloplastic implant related problem (fig. 1) followed by foreign body reaction, extrusion, and infection. Deviation of the implant is often the result of careless insertion of the implant after asymmetric dissection of the implant pocket, which is usually performed endonasally. Other reasons may include too large a pocket size for the implant or failure to recognize preexisting deviations. Often, patients can have preexisting deviations which are inconspicuous due to the low height of their dorsum but can become apparent after the nose is augmented. When performing revision surgery for a deviated implant, the first step is to ensure that the underlying nose is straight. If the nose is deviated, correction of the deviated nose must be performed before further augmentation can take place. Most cases of silicone implants include surrounding capsules that are deviated as well. Leaving them in situ can lead to persistent deviation. Therefore, the capsule is removed as much as possible, taking care to avoid damaging the skin soft tissue envelope (fig. 2). Careful symmetric dissection of the subperiosteal pocket, which is appropriate in size and that is large enough to accommodate the implant’s snug fit into the pocket, can minimize the chances of displacement.

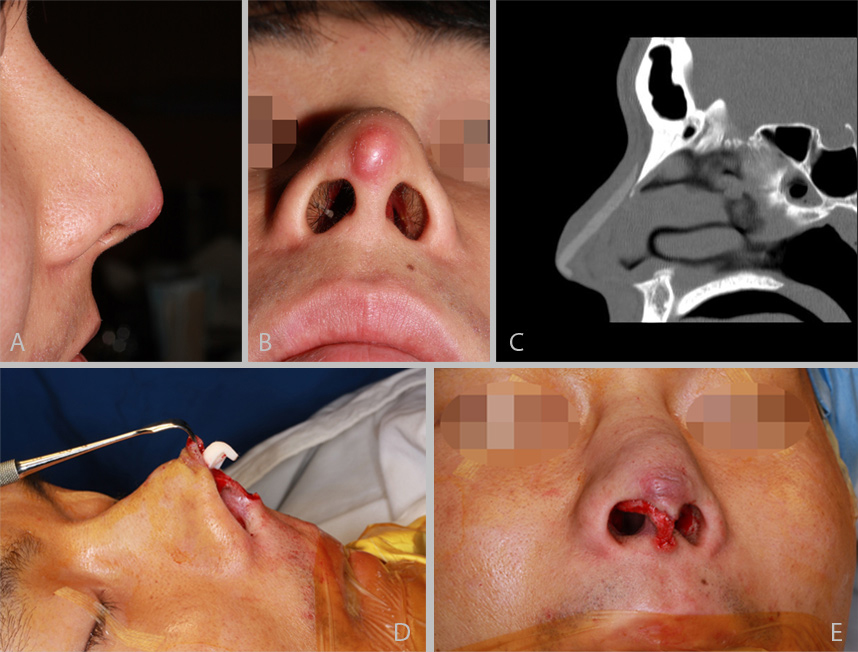

Extrusion of implant

Most extrusion occurs when the implants extends to the nasal tip (fig. 3). The implant causes thinning of the tip skin with resultant extrusion through the membranous septum or even through the tip skin. In rare occasion, the implant extrudes through radix skin (fig. 4). Adequate management of the damaged skin is important in these patients. Autologous fascia or allogenic acellular dermal matrix (Alloderm) is useful in camouflaging the damaged skin. To avoid extrusion, the implant must be designed to avoid overaugmentation and fashioned to augment only the dorsum. Usually, the implant should not exceed caudally the anterior septal angle. The tip is augmented only with autologous tissue.

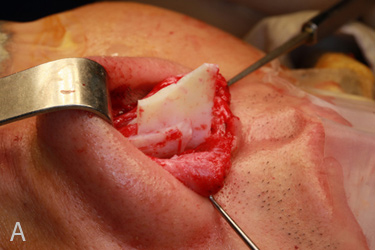

Infection of implant

Infection occurs early or late even after years after the surgery (fig. 5). In cases of infection, I usually remove the implant along with any surrounding necrotic tissue, irrigate the nose with antibiotics, and concurrently perform revision surgery with autologous grafting material (fig. 6). It is my opinion that it is more prudent to remove the implant at an earlier stage than to wait for infection control with medical treatment since antibiotics can rarely resolve the situation and the events are prone to recur.16 To avoid infection when using alloplastic implants, I take extra precautions that include preparing the nose with cotton balls soaked in betadine solution, frequent irrigation of the nose with antibiotic solution, and careful handling of the implant. The implant is designed aseptically with new gloves and inserted after being soaked in antibiotic solution.

Postoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics are given for two weeks. Insertion in the proper subperiosteal plane is also important since the periosteum can serve as a natural barrier.

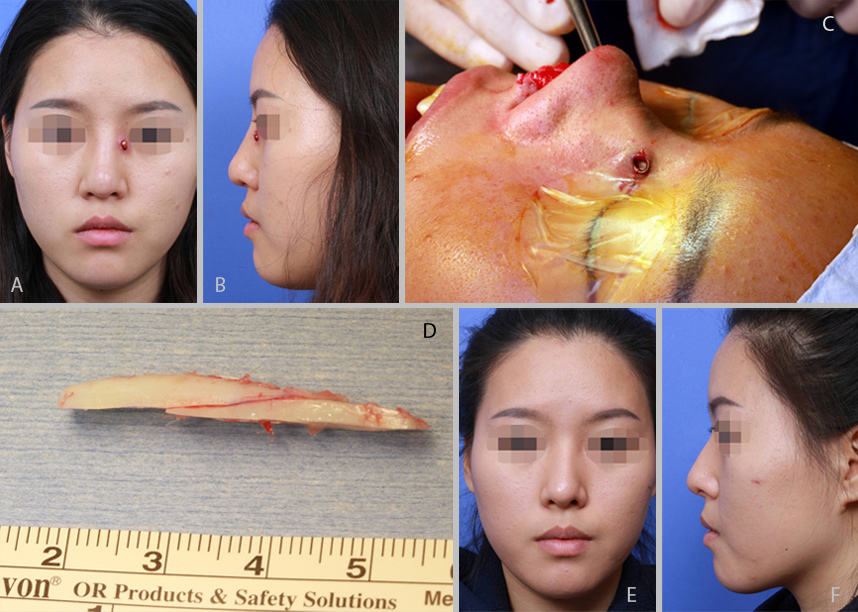

Operated look

The unnatural operated look is caused primarily by two reasons. One is the very conspicuous indication of the implant, causing the so-called “toothbrush handle look” in the frontal view (fig. 7a) while the other is too high radix (fig. 7b) from the frontal and lateral views.

Revision in this case is performed with attention to the starting point of the nose in the radix. To avoid this unnatural look, it is worthwhile to refrain from using hard alloplastic implants such as silicone in thin-skinned Asian patients.

Over-augmentation should also be avoided since it can cause skin thinning over time. Foundhair.com The implant should be designed carefully to ensure that the nasal starting point is near the midpupillary line.

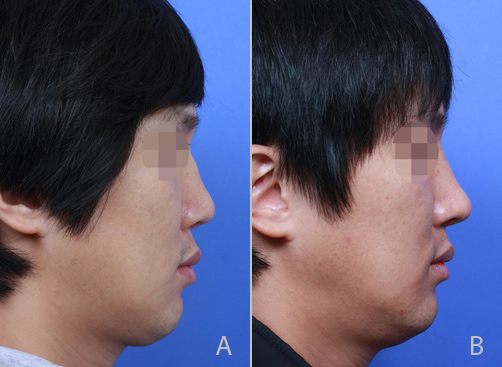

Contracted, short nose

The contracted nose associated with alloplastic implants presents a major challenge (fig. 8).19 It frequently develops after removal of longstanding alloplastic implants (especially silicone or Gore-Tex) due to scar contracture caused by the secondary structural changes in the bone and cartilage beneath the implant as well as in the SSTE superficial to them.

Wide release of the contracted skin and lower lateral cartilage, building a firm foundation with autologous grafting material that can counteract the contractile forces of the SSTE, and additional graft on the tip and dorsum are key maneuvers for lengthening the contracted nose; therefore, rib cartilage is used in most cases (fig. 9). Unfortunately, the only way to avoid contracture associated with alloplastic implants is by not using them.

Doral and tip problems

Frequent problems of the upper two-thirds of the nose are residual deviation or dorsal irregularities (fig. 10). As tip surgery is more commonly performed recently, tip problems such as asymmetry, polly beak deformity, under-projection, or over-rotation are also increasing. While dorsal problems are more common than tip problems in Asian, Caucasians tend to have more problems on the tip.20,21 Thicker tip skin concealing minor irregularities and a frequent need for dorsal augmentation in Asian can be an explanation for this phenomenon.

Revision techniques in this group are chosen depending on the etiology. Septal reconstruction, complete osteotomies, onlay, and camouflage grafts are used to correct the upper two-thirds. Extended spreader grafts, septal extension grafts, and onlay grafts are used to control the rotation and projection of the tip with additional alar batten, rim grafts, composite grafts, and alar base resection for further refinement of the tip (fig. 11).

Functional problems

Main etiologies of functional problems in Asian rhinoplasty are missed or incomplete correction of septal deformity, untreated allergy or turbinate dysfunction. On the other hand, a considerable portion of functional problems are derived from nasal valve dysfunction in Caucasian rhinoplasty.23, 24 This is because most Asian rhinoplasty includes augmentation while reduction or resection, which can be a potential source of functional problems, is relatively more frequent in Caucasian rhinoplasty.

Conclusion

Majority of revision rhinoplasties in Asians are associated with alloplastic implants or dorsal problems. Recent increase in tip revision reflects the increase of open rhinoplasty techniques. Proper management of these problems of revision Asian rhinoplasty needs thorough understanding of Asian nasal anatomy, proper consultation based on the Asian cultures and heritage, mastering of techniques unique to Asian rhinoplasty, and proper use of graft materials including rib cartilage. Experiences in handling problems unique to Asian revision rhinoplasty need a continuous exposure to various cases with cultural and technical assimilation.

References

- Zingaro EA, Falces E. Aesthetic anatomy of the non-caucatian nose. Clin Plast Surg.1987;14(4):749-765.

- Aung SC, Foo CL, Lee ST. Three dimensional laser scan assessment of the Oriental nose with a new classification of Oriental nasal types. Br J Plast Surg. 2000;53(2):109-116.

- Wu WT. The Oriental nose: an anatomical basis for surgery. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1992;21(2):176-189.

- Kridel RW, Yee S. Psychological, financial and legal considerations in secondary rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1995;3:347–351.

- Walter C. Revision surgery. In: Nolst Trenite GJ, ed. Rhinoplasty: A Practical Guide to Functional and Aesthetic Surgery of the Nose, 2nd ed. Kugler Publications; 1998:209–223.

- Park CH, Kim IW, Hong SM, Lee JH. Revision rhinoplasty of Asian noses: analysis and treatment. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(2):146-155.

- Lam SM. Revision Rhinoplasty for the Asian Nose. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(3):372-377.

- Ahn JM. The current trend in augmentation rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2006 ;22(1):61-9.

- Zeng Y, Wu W, Yu H, et al. Silicone implant in augmentation rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:495– 499.

- Ahn JM, Honrado C, Horn C. Combined silicone and cartilage implants: augmentation rhinoplasty in Asian patients. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(2):120-123.

- Deva AK, Merten S, Chang L. Silicone in nasal augmentation rhinoplasty: a decade of clinical experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1230-1237.

- Tham C, Lai YL, Weng CJ, Chen YR. Silicone augmentation rhinoplasty in an Oriental population. Ann Plast Surg. 2005 Jan;54(1):1-5.

- Shirakabe, Y., Suzuki, Y., and Lam, S. M. A systematic approach to rhinoplasty of the Japanese nose: A thirty-year experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003;27: 221-231.

- Lohuis, P. J., Watts, S. J., and Vuyk, H. D. Augmentation of the nasal dorsum using Gore-Tex: Intermediate results of a retrospective analysis of experience in 66 patients. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001; 26(3):214-217.

- Godin MS, Waldman SR, and Johnson CM. Nasal augmentation using Gore-Tex: A 10-year experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1:118–121.

- Jin HR, Lee JY, Yeon JY, Rhee CS. A multicenter evaluation of the safety of Gore-Tex as an implant in Asian rhinoplasty. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20(6):615-619.

- Peled ZM, Warren AG, Johnston P, Yaremchuk MJ. The use of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty surgery: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):85-92.

- Won TB, Jin HR. Revision rhinoplasty in Asians. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65(4):379-384.

- Jung DH, Moon HJ, Choi SH, Lam SM. Secondary rhinoplasty of the Asian nose: correction of the contracted nose. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:1–7.

- Vuyk HD, Watts SJ. Revision rhinoplasty: review of deformities, aetiology and treatment strategies. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25(6):476-481.

- Parkes ML, Kanodia R, Michadia BK. Revision rhinoplasty: an analysis of aesthetic deformities. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(7):695-701.

- Jin HR, Lee JY, Shin SO, et al. Key maneuvers for successful correction of a deviated nose in Asians. Am J Rhinol.2006(6);20:609-614.

- Ballert JA, Park SS. Functional considerations in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2008;24(3):348-357.

- Suh Mw, Jin HR, Kim JH. Computed tomography versus nasal endoscopy for the measurement of internal nasal valve in Asians. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:675-679.