Five Techniques That I Cannot Live Without in Revision Rhinoplasty

Daniel G. Becker, M.D., F.A.C.S.,1 and Jason Bloom, M.D.

Introduction

Like most surgeries, revision rhinoplasty is both a science and an art. Consistent success in revision rhinoplasty requires well-developed judgment, wisdom, and accumulated knowledge and experience. The revision surgeon must have a detailed understanding of the multiple anatomic variants encountered. The surgeon must also have accumulated the appropriate surgical techniques and experience. Specifically, the revision surgeon must acquire knowledge of the surgical alterations that occur and how to achieve an improvement or correction when the result is undesirable. These skill sets are strengthened and refined by careful follow-up of operated patients over time.

The nationally reported revision rate for primary rhinoplasty ranges from 8 to 15%.1–8 Sadly, there will likely never be a shortage of patients requiring revision rhinoplasty. Experienced revision surgeons consistently achieve a high level of satisfaction among their patients. Still, complications can occur despite technically wellperformed surgery. All surgeons have complications. Revision surgery is different from primary surgery.

The tissue planes have often been obliterated, precious tissue overresected and/or asymmetrically resected, and healing forces have distorted weak or weakened cartilages.The elasticity and quality of the skin–soft tissue envelope is a critical limiting factor in revision surgery and must be factored into the surgical plan. Also, the revision surgeon must undertake a careful analysis of the existing cartilage and bony structure. This requires analysis of the existing structure and a mental reconstruction of the patient’s “normal” preoperative anatomy.

A detailed discourse of problems encountered in the revision patient and various approaches to treatment of these problems will be found in this issue of Facial Plastic Surgery and also in a recent textbook.9 For this article, the senior author was asked to select five surgical techniques, ‘‘pearls’’ from my revision rhinoplasty practice that I believe warrant highlighting. Whereas this is far from being an exhaustive list of techniques, it is our hope that this information will be useful to the reader and will stimulate the reader to further study.

Hump Reduction Under Direct Visualization

Throughout the years, many surgeons have shown that the bony pyramid can be reliably reduced, repositioned, or augmented through an endonasal approach. Larrabee, however, reports that open rhinoplasty may allow more precise contour refining of the nasal dorsum.He explains that the incidence of profile irregularities may be reduced when procedures are performed via the open approach.10 Larrabee suggests that the benefits of increased exposure to the dorsum, available with the open rhinoplasty approach, should be exploited whenever possible.10 He points out that there is a tendency of some surgeons to treat the bony pyramid in an essentially closed fashion, even when using the open approach.10 In the experience of the senior author (D.G.B.), a closed approach has been reliable for addressing most bony profile problems. However, when performing an open rhinoplasty, the senior author now prefers to undertake hump reduction under direct visualization. With this open approach to the nasal dorsum and because of technical differences relating to the skin positioning, the rhinoplasty surgeon may require a different (i.e., narrower) osteotome from that which was previously used for “closed” hump reduction.

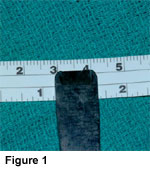

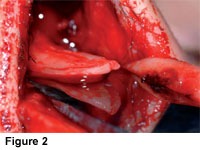

The senior author found that an 8-mm unguarded osteotome is preferable for most bony hump reductions when using an open approach (Figs. 1 and 2). Significantly wider osteotomes may be too wide and can cause injury to the skin–soft tissue envelope when using an open approach.

When the “closed” approach is used, the skin–soft tissue envelope is redraped into anatomic position before the hump excision, and awider osteotome can be accommodated. However, this additional width is not necessary for an open approach. The osteotome needs to be only as wide as the widest point of the hump resection, typically at the rhinion. When using an osteotome for dorsal hump excision under direct visualization, the 8-mm nonguarded osteotome provides a sharp cutting surface and precise size for this procedure. At times-when the patient has a very large hump -a wider osteotome may be preferable. This approach has been especially useful in revision patients where underresection or asymmetric resection has occurred (Figs. 3–6). It has been the senior author’s impression that the direct visualization afforded by this approach allows for more precision in these difficult revision situations.

Powered Rasp

An alternative to the manual rasp, and the senior author’s preferred approach, is a powered reciprocating rasp.11–13 These instruments can be used wherever a manual rasp would be used, but with less soft tissue trauma, especially when the site to be treated can be directly visualized. The powered instruments are especially useful to smooth the bony margins of the “open roof.” Also, they are useful to correct isolated bony irregularities that may be encountered, for example, in revision rhinoplasty. When using these powered reciprocating rasps, it appears that one can obtain a more reproducible result with a lower incidence of visible or palpable bony dorsal irregularities.

There have been advances in instrumentation for powered rasping. Until recently, the author preferred the Linvatec-Hall Surgical (Linvatec Corporation, Clearwater, FL) powered rasp. This electrical powered reciprocating device is already available in many operating rooms, and a reusable rasp attachment is available. Although this rasp remains most satisfactory, the senior author has now switched to primary use of an air-driven powered reciprocating rasp (Figs. 7 and 8). The senior author believes that the higher reciprocating speed and other handling characteristics are advantageous.

Diagnostic Nasal Endoscopy and Endoscopic Septoplasty

Diagnostic nasal endoscopy is a critical aspect of the evaluation of the revision rhinoplasty patient who reports nasal obstruction (Fig. 9). Pownell et al have described diagnostic nasal endoscopy in the plastic surgical literature.14 They trace the historical development of nasal endoscopy, explain its rationale, review anatomic and diagnostic issues including the differential diagnosis of nasal obstruction, and describe the selection of equipment and correct application of technique, emphasizing the potential for advanced diagnostic potential.

Levine reported that 39% of patients with a complaint of nasal obstruction had findings on endoscopic examination that were not identified with traditional rhinoscopy. Many of Levine’s patients had seen other physicians for this problem and had not received appropriate treatment. Becker et al described that, in patients seeking cosmetic nasal surgery who also had nasal obstruction, nasal endoscopy (Fig. 9) allowed the diagnosis of additional pathology not seen on anterior rhinoscopy, including obstructing adenoids, enlarged middle turbinates with concha bullosa, choanal stenosis, nasal polyps, and chronic sinusitis. In this series, additional surgical therapy was undertaken in 28 of 96 rhinoplasty patients due to findings on endoscopic exam. Thirteen patients had endoscopic sinus surgery. Nine patients had a concha bullosa requiring partial middle turbinectomy. Three patients—all revision surgeries—had persisting posterior septal deviation requiring endoscopic septoplasty. Two patients underwent adenoidectomy. One patient required repair of choanal stenosis.

As alluded to above, if septal deviation persists posteriorly after a septoplasty, persisting nasal obstruction may require revision septoplasty. Because the mucosal flaps are often densely adherent after a septoplasty, revision septoplasty involving a traditional approach may present technical difficulty, including significant risk of septal perforation.

Endoscopic septoplasty is a relatively recent and important technique that has direct application in this situation. The endoscopic approach may be a useful adjunct in these difficult revision cases in which a complete elevation of the mucoperichondrial flap presents difficulties, such as persistent posterior septal obstruction after prior septoplasty or prior septal injury (such as hematoma or abscess) with loss of cartilaginous septum. In these cases, typical surgical dissection planes are obliterated and complete elevation of the mucoperichondrial or mucoperiosteal flaps may be difficult. The ability to address a persisting deviation, elevating the mucosal flap directly over the offending deviation using endoscopic techniques, greatly facilitates treatment. Indeed, Becker and Kallman report that in a series of 90 primary septorhinoplasties, one patient underwent endoscopic septoplasty. In 23 revision functional septorhinoplasties, 4 patients benefited from endoscopic septoplasty approaches.

Most rhinologic (i.e., sinus) surgeons are familiar with the benefits of diagnostic endoscopy and endoscopic surgical techniques in the context of sinus and nasal dysfunction. However, these advantages may not be as widely recognized in the rhinoplasty community. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy, and endoscopic techniques including endoscopic septoplasty, are important tools in the revision rhinoplasty surgeon’s armamentarium.

Endoscopic septoplasty is a well-described technique for correction of septal deformities.18–23 First described in 1991,18 its use has been reported for the treatment of isolated septal spurs18–21 and in the treatment of more broad-based septal deformities.22 Advantages of the endoscopic technique include potentially improved visualization of posterior septal deformities, the opportunity for limited minimally invasive procedures, and potential improved access in certain revision cases.

Endoscopic septoplasty offers distinctive advantages in selected difficult cases of revision septoplasty. 17,21 Whereas septoplasty does not commonly require endoscopic approaches, the endoscopic approach may be a useful adjunct in difficult revision cases in which complete elevation of a mucoperichondrial flap presents difficulties. Examples include a persistent posterior septal obstruction after prior septoplasty or after septal injury (such as hematoma or abscess) with loss of cartilaginous septum. In these cases, typical surgical dissection planes are obliterated, and complete elevation of a mucoperichondrial or mucoperiosteal flap may be difficult. The ability to directly address a persisting deviation, elevating the mucosal flap directly over the offending deviation using endoscopic techniques, greatly facilitates treatment.

The technique of endoscopic septoplasty has been well-described.17–23 For a broadly based Figure 9 septal deviation, a standard Killian or hemitransfixion incision may be made. For an isolated posterior deformity, the incision may be positioned in the immediate vicinity of the deformity. Mucoperichondrial and mucoperiosteal flap elevation is facilitated by a suction elevator. For a broadbased deviation, the septal cartilage may be incised and the contralateral mucoperichondrial and mucoperiosteal flaps are elevated, taking great care to preserve a generous L-strut of at least 15 mm for continued nasal support. If an isolated posterior deformity is addressed, the cartilage or bone is incised several millimeters posterior to the mucosal incision, and the contralateral mucosal flap is elevated. Deviated portions of septal cartilage and bone are corrected or removed. Straightened or morselized cartilage may be replaced, and the septal flaps may be closed with a quilting suture, although in more limited cases suturing may not be necessary.

Computer Imaging

The senior author’s philosophy of revision rhinoplasty is driven by one essential goal—to make the patient happy. Clear communication between surgeon and patient, and clear understanding of the patient’s surgical goals, are important ingredients for success. Though obviously not a surgical technique, computer imaging has been an indispensable communication tool in revision rhinoplasty and warrants highlighting here. The senior author rarely performs cosmetic rhinoplasty when computer imaging has not been performed.

The senior author’s office computer network provides for imaging in each examination room. The patient’s photos are uploaded onto the computer screen in the examination room, and computer imaging is undertaken.

The senior author explains to the patient that computer imaging is just a “video game,” that it is a way to communicate a shared surgical goal. It is further explained that of course this is not an “after” picture, that it is not a guarantee and should not be taken to even offer the slightest implication of a guarantee. It is simply a way to communicate the shared surgical goal. The senior author does not provide the patient with printouts of the computer imaging.

The senior author explains to the patient that he routinely prints out the preoperative photo and shared surgical goal photo and tapes them to the wall in the operating room during surgery, so that he can refer to the pictures as surgery progresses.

Composite Graft for Alar Retraction

Auricular composite grafts are commonly used in more severe cases of alar retraction.9,24,25 It has been the senior author’s experience that the skin and cartilage of the anterolateral surface of the ear, just inferior to the inferior crus, of the opposite ear (example, left ala, right ear) provides the best donor site and the best contour (Fig. 10). If a small composite graft is needed, primary closure of the donor site may be achieved. If a large graft is required, a “revolving door” postauricular flap may facilitate closure (Figs. 10–15).

Composite grafts are easiest to place when undertaking a limited, precise pocket approach. When more extensive revision rhinoplasty is being performed, with wider elevation undertaken, one may have concern that the composite graft will not stay in position. However, the senior author has not found this to be the case. Composite grafts may be used in conjunction with alar batten grafts.

An incision several millimeters from the nostril rim is followed by careful dissection with freeing of adhesions, creating a defect and displacing the alar rim inferiorly. Volume and support must be restored to hold the nostril rim in position—this role is fulfilled by the composite graft. The fashioned composite graft is carefully sutured into place.9,24,25 Typically, the senior author uses 5-0 chromic suture. I place a cotton ball or other light dressing intranasally to apply light pressure for 1 to 3 days (Figs. 16 and 17).

Composite grafts are easiest to place when undertaking a limited, precise pocket approach. When more extensive revision rhinoplasty is being performed, with wider elevation undertaken, one may have concern that the composite graft will not stay in position. However, the senior author has not found this to be the case. Composite grafts may be used in conjunction with alar batten grafts.

References

- Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997

- Kamer FM, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, ed. Head and Neck Surgery Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1998

- Rees TD. Postoperative considerations and complications. In: Rees TD, ed. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1980

- McKinney P, Cook JQ. A critical evaluation of 200 rhinoplasties. Ann Plast Surg 1981;7:357–361

- Thomas JR, Tardy ME. Complications of rhinoplasty. Ear Nose Throat J 1986;65:19–34

- Tardy ME, Cheng EY, Jernstrom V. Misadventures in nasal tip surgery: analysis and repair. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20:797–823

- Simons RL, Gallo JF. Rhinoplasty complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1994;2:521–529

- Becker DG. Complications in rhinoplasty. In: Papel ID, ed. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2002:452– 460

- Becker DG, Park SS. Revision Rhinoplasty. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers

- Larrabee WF Jr. Open rhinoplasty and the upper third of the nose. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1993;1:23– 38

- Becker DG, Park SS, Toriumi DM. Powered instrumentation for rhinoplasty and septoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1999;32:683–693

- Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME. Powered instrumentation for dorsal nasal reduction. Facial Plast Surg 1997;13:291–297

- Becker DG. The powered rasp: advanced instrumentation for rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2002;4:267–268

- Pownell PH, Minoli JJ, Rohrich RJ. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;99:1451–1458

- Levine HL. The office diagnosis of nasal and sinus disorders using rigid nasal endoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;102:370–373

- Becker, et al. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy in functional septorhinoplasty

- Becker DG, Kallman J. Endoscopic septoplasty in functional septorhinoplasty. Oper Techn Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000

- Lanza DC, Kennedy DW, Zinreich SJ. Nasal endoscopy and its surgical applications. In: Lee KJ, ed. Essential Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, 5th ed. New York, NY: Medical Examination Publishing Co; 1991: 373–387

- Lanza DC, Rosin DF, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic septal spur resection. Am J Rhinol 1993;7:213–216

- Cantrell H. Limited septoplasty for endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;116:274–277

- Giles WC, Gross CW, Abram AC, et al. Endoscopic septoplasty. Laryngoscope 1994;104:1507–1509

- Hwang PH, McLaughlin RB, Lanza DC, Kennedy DW. Endoscopic septoplasty: indications, technique, and results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:678–682

- Stamberger H. Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: The Messerklinger Technique. Philadelphia, PA: BC Decker; 1991:432–433

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Alar retraction: composite graft correction. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6:101–107

- Tardy ME, Genack SH, Murrell GL. Aesthetic correction of alar-columellar disproportion. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 1995;3:395–v406