Nasal surgery can be traced back to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics in 600 B.C. Roe was the first to describe a surgical approach to alteration of the nasal tip in 1887, which was later optimized by Joseph—widely recognized as the father of modern corrective rhinoplasty.1 One of the most challenging elements of rhinoplasty is aesthetic optimization of the nasal tip. The overprojected nasal tip, commonly referred to at the Pinocchio- or Cyrano de Bergerac-type nose, is an uncommon but challenging feature to manipulate for modern facial plastics surgeons. Nasal tip projection is defined as the distance that the nasal tip travels anterior to the facial plane. There are many nasofacial measurements that have been created to characterize ideal tip projection. Goode described an ideal dimension of projection when the alar-facial groove to nasal tip measures 0.55-0.60 of the distance from the nasion to the nasal tip, creating a 36-degree nasofacial angle. Simons posited the distance from the subnasale to the tip defining point to equal that of the subnasale to the vermilion border of upper lip in an ideally projected nose. Crumley’s 3-4-5 ratio dictated a proportional relationship where the nasal profile is a right angle with vertices at the nasion, tip-defining profile, and alar crease.3 In this chapter we will review the Anderson tripod theory of tip projection, and thoroughly describe the most popular techniques for tip deprojection including: (1)transfixion incision, (2) medial and/or lateral crural overlay, and (3) dome truncation. We will also review miscellaneous

techniques that can assist in tip deprojection in addition to the aforementioned methods.

Anderson Tripod Theory

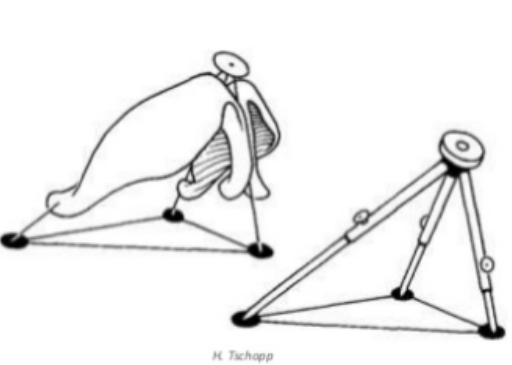

In order to gain a complete understanding of tip deprojection manipulation, a comprehensive approach to the nasal tip is paramount. The primary nasal tip support mechanisms are: (1) the fibrous attachments between the medial crural footplates and nasal septum; (2) the attachments between the upper and lower lateral cartilages; and (3) the size, shape, and resilience of the lower lateral cartilages. Minor tip support mechanisms include the septal dorsum, interdomal ligament, Pitanguy ligament, membranous septum, nasal spine, attachments of the lower lateral cartilages to the soft tissue envelope, and the minor sesamoid cartilage piriform attachments.4 The structural architecture of the nasal tip has been conceptualized into several theories; perhaps the most prominent is the tripod theory of Anderson. The tripod theory anatomically describes the nasal tip support structure as a functional tripod. The right and left lateral crura comprise two legs of the tripod, while the two conjoined medial crura form the third leg. The apex of

the tripod is considered to be the tip of the nose, and essentially rests on the anterior nasal spine. It is supported laterally by attachments to the sesamoid cartilages/piriform and superiorly by the upper lateral cartilage in the scroll region. Anderson described ways to modify this pyramid through rotation, derotation and deprojection by modifying

the relative lengths of the three arms of the tripod (Figure 1).

There are additional theories of nasal tip support that have been iterated in recent times, predominantly the M-arch model, 3-dimensional nasal tip mode, and the “cantilevered spring model” proposed by Friedman and Westreich, respectively.6 The M-arch model described by Adamson et. al suggested that the nasal tripod could be conceived as one arch of a specific length. Vertical division along any point on this arch can refine tip placement by increasing rotation along the axis of the arch. The 3 dimensional nasal tip model considers craniocaudal changes in alar positioning when modifying columella and/or tip lobule components of the nasal tip.7 The cantilevered spring model describes a single fixation point between the lower lateral cartilages and caudal septum with a cranially directed spring-like elastic force mobilizing the free ends of alar cartilage. The authors argued that the theory is more inclusive of various nasal frameworks and ethnicities, while previous theories have structurally been limited to the leptorrhine nose.

Overprojection of the nasal tip is most often caused by a combination of multiple features, including:

- A strong nasal spine

- Overdeveloped medial and/or lateral crura

- Overprojected anterior septal angle and dorsal septum

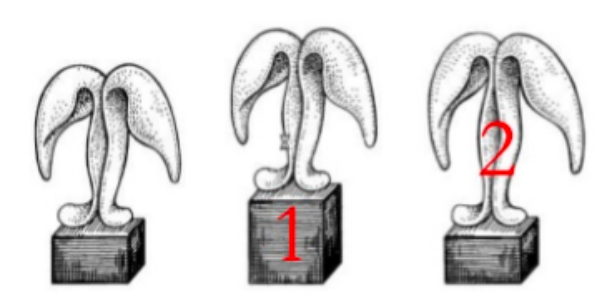

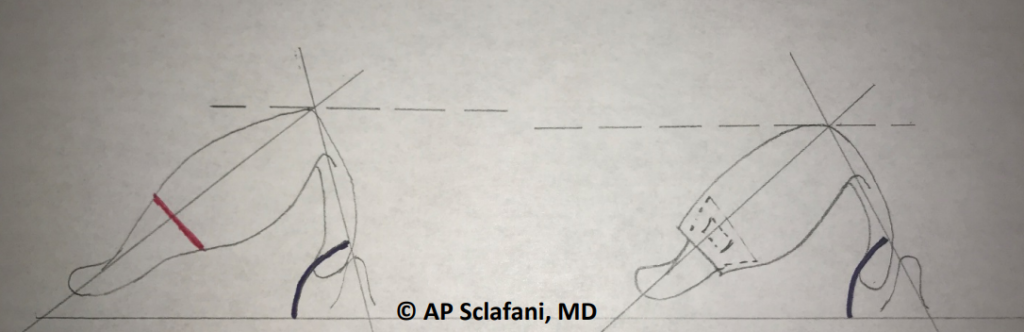

A thorough evaluation of the profile of the radix is essential to a complete understanding of nasal projection and the maneuvers needed to deproject the nasal profile. Due to the illusionary effect of the radix on the nasal profile, often a simple radix graft is all that is needed to optimize the balance of dorsal and tip projection. If one imagines the nasal tip sitting on wooden block that represents the nasal spine and caudal margin of the nasal septum, a simple reductive solution to nasal overprojection is possible (Figure 2). The medial crura are supported by the anterior nasal spine in such a manner that a reduction of the spine will deproject the nasal tip by leaving the medial crura in a lower position. The caudal septum can also be trimmed in cases of tip overprojection secondary to caudal septal hypertrophy, or the so- called “tension nose.” We will next examine the most common direct surgical maneuvers and methods available to the rhinoplasty surgeon for deprojection of the nasal tip.

Transfixion Incision

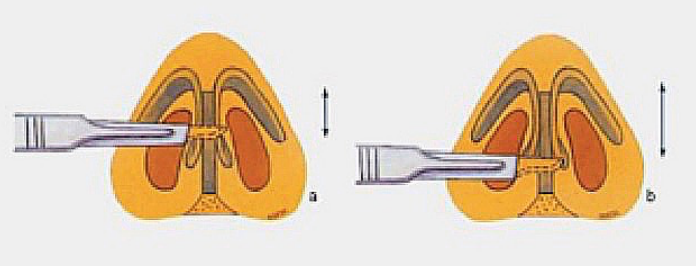

Once the radix is evaluated, one must consider altering tip structure in order to achieve adequate deprojection. The major tip support mechanisms of the nose are crucial to consider when understanding deprojection, in particular the attachment of the medial crura to the nasal septum. Tip deprojection can hence first be subtly achieved by performing a full transfixion incision (Figure 3). A full transfixion decreases tip support and consequently slightly deprojects the nasal tip.8 With a hemitransfixion approach, the medial crural support “leg” is not compromised. Solomon et al. reviewed a series of 72 patients in which a transfixion incision was performed to facilitate deprojection, noting a mean reduction in projection of 1.6mm immediately after incision, and 2.4mm when combined with other procedures.9 This incision can also be extended to bilateral intercartilaginous incisions and superiorly and vestibular incisions inferiorly; this is otherwise known as the ‘extended transfixion’ incision.

Consequences of this maneuver include a drooping tip and a more acute nasal labial angle because the medial leg of the tripod support is disrupted, biasing it in the direction of the shorter leg. However, foreshortening both lateral crura and performing a full transfixion will result in net retrodisplacement without changes in rotation.10 If cephalic

tip rotation is desired, shortening of the lateral crura and increased medial crural support (i.e. cartilaginous columellar strut, septal columellar suture, propping grafts), results in cephalic rotation because the medial leg of the tripod becomes the dominant leg.

Medial and Lateral Crural Overlay

The concept of modifying nasal tip projection by interrupting the continuity of alar cartilages was first introduced in the 1930s by Joseph and Safian. These techniques can generally be divided into two categories: sacrificing the domal segments (as in dome truncation) or by preserving the domes but shortening the medial and/or lateral crura.

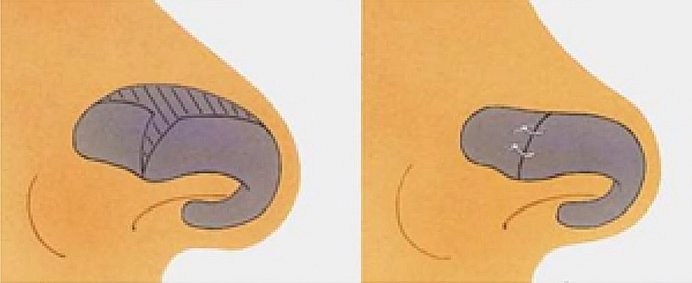

Shortening of the lateral crura can be achieved by several means. An interrupted strip, by which the lateral crura are cut and sutured primarily end-to-end, can offer reliable shortening and tip deprojection (Figure 4). This can be superimposed with a cephalic trim and ultimately results in increased rotation as well as deprojection of the nasal tip. This was first popularized by Webster and Smith12 who developed the lateral crural flap technique, in which the lateral crural cartilage was divided cephalic to its divergence from the alar rim, leaving the free edge of the lateral crus unfixed and mobile but offering deprojection/derotation by destabilizing the lateral crura. A derivative of this technique that has gained popularity is the lateral crural overlay (LCO), which is designed to increase tip rotation in addition to deprojection, while stabilizing the lateral crura in the postoperative period (Figure 5). In this approach the lateral crura are transected vertically 10mm lateral to the domes in an open approach after elevating the vestibular skin. The cut ends are then overlayed and secured with a transcartilaginous horizontal mattress-type suture.13,14 Pulling the lateral crural to perform the overlay essentially decreases the effective “length” of the lateral crural legs of the nasal tripod, increasing rotation.

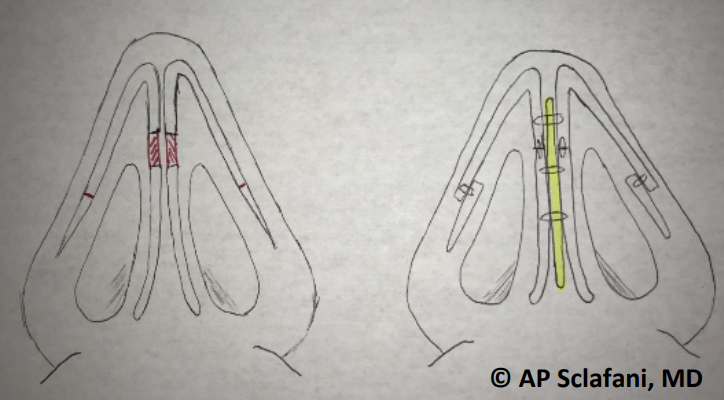

A similar maneuver can be performed with a medial crural overlay, or Lipsett maneuver. After elevation of vestibular skin, the medial crura are transected at the central portion. The location of the transection depends on the desired columellar-lobule ratio. The medical crura are then overlaid and secured with a transcartilaginous mattress

suture. This shortens the central leg of Anderson’s tripod, resulting in decreased rotation as well as decreased tip projection. When both crura are overlayed the net rotation will be unchanged, but tip projection will decrease. This segment can also be resected primarily in the same manner.

Alar Setback/Medial Crural Resection

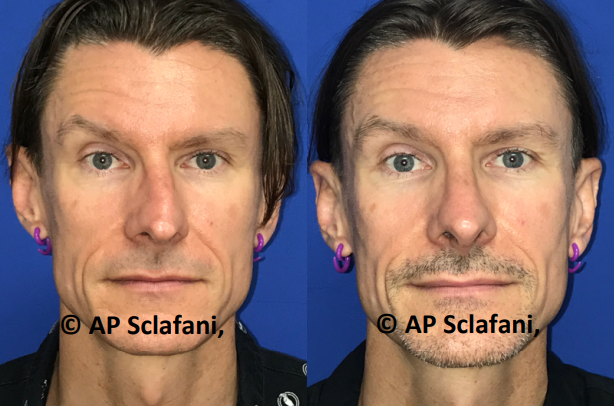

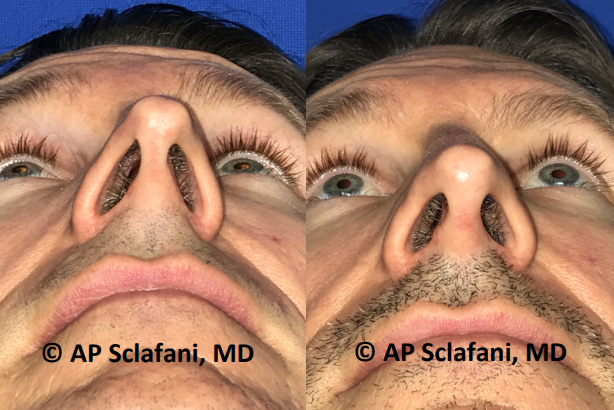

In the alar setback technique described by Foda et al., a 3-6 mm segment of medial crural cartilage is excised in a region along the columellar lobule border with reapproximation using a columellar strut graft to splint the reconstruction in the midline (see Supplementary Video 1 for demonstration of medial crural resection). 15 The location of the setback depends on the pre-existing lobule-to-columella ratio. If the columella is disproportionally longer than the lobule, a “low” setback is performed in which the resected medial crural cartilage is closer to the nasal base than the tip. If there is redundancy in the tip lobule, then a high setback is performed to avoid unnatural

lobule-columellar disproportion (Figure 6). Medial crural setback and columellar strut fixation techniques can precede a lateral crural overlay, for example, which would result in an unchanged rotation of the tip. Other rotation modifying techniques can be employed reliably with alar setback to achieve desired rotation in addition to deprojection. Sample pre-/post-operative photographs for medial crural resection can be seen in Figure 7.

Dome Truncation

This method was first described by Safian in 1970, and later modified by Smith to describe pulling of medial/lateral crura to create a new dome.16 If aggressive tip deprojection is desired, bilateral domes can be truncated. This is performed with a permanent mattress suture across the dome through the lateral and medial crura, with care to bury the suture internally. In order to maintain the relationship between the crura and leave rotation unchanged, the suture must be oriented parallel to the plane of dome truncation immediately posterior to the intended truncation site. If the inferior margin of the new crural junction is slightly anterior to the cephalic margin, a supratip break will be seen along the new profile line without unwanted changes to the tip. If further tip refinement is desired, an additional interdomal suture can be placed in close proximity to the first. Often the sharp edges following truncation are camouflaged with a small shield graft onlay (Figure 8).

Universal Retraction Suture

The retraction suture reapproximates the anterior septum in relation to the medial crura/membranous septum. It is designed to displace the columella posteriorly. Fanous et al. described an essential horizontal mattress suture through cartilaginous septum and columella at a relative anterior location to displace the columella backward. This is ideal for revision cases in which no alterations in rotation are desired. This retrodisplacement can create undesired nasal flaring at alar base, and an alar base reduction can be performed as compensation.

This can also be performed by resetting the feet of the medial crura directly to the caudal septum in to achieve the same effect (Supplementary Video 2, “Reset of Medial Crura Attachment to Nasal Septum”). This technique has alternatively been termed the ‘tongue-ingroove’ setback technique; the ‘groove’ is the surgically created space between the membranous nasal septum and both medial crura and the ‘tongue’ is the caudal septum. Figure 9 exemplifies postoperative results of this tip deprojection suture.

Surgical Algorithms for Tip Deprojection in Rhinoplasty

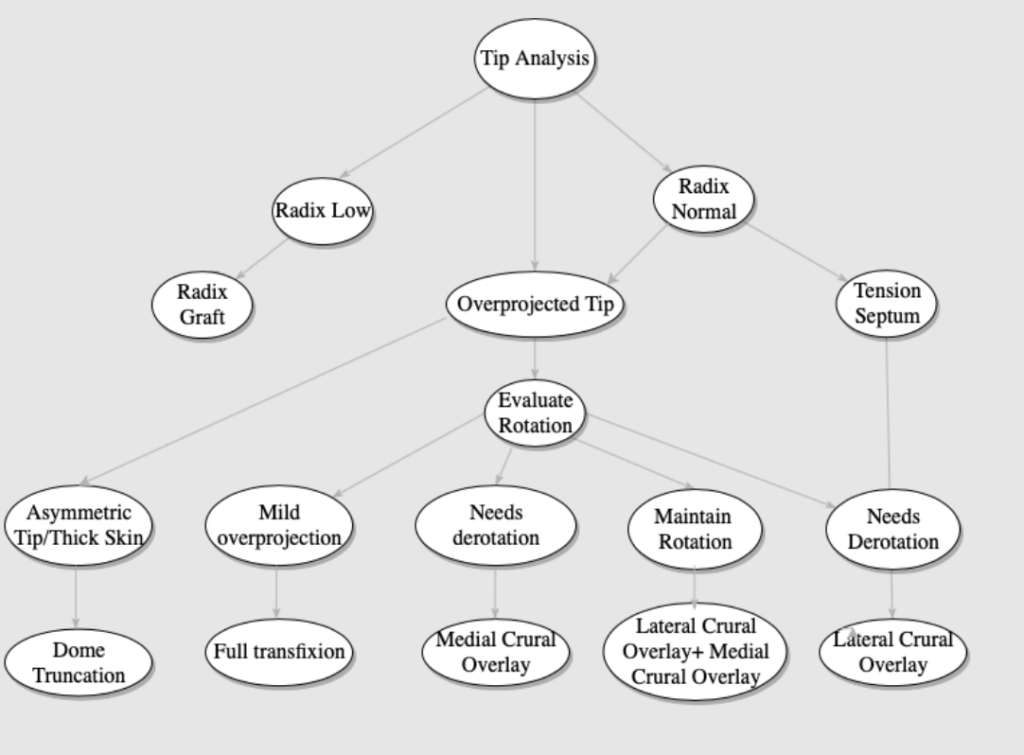

Kridel et al. suggested a systematic algorithm for nasal tip deprojection considering the relative effects of medial and lateral crural overlay and the overall contribution of a tension septum or low radix to tip projection (Figure 10).

A tension septum can be addressed by lowering the caudal septum or dorsum, while the low radix can be augmented with a radix graft. These maneuvers correct the illusionary nasofacial features that can increase perceived projection without altering the nasal tip itself.

Both lateral and medial crural overlay have the advantage of the surgeon being able to make real time adjustments in shape and contour, as there is no cartilage excised. If too much deprojection is seen, the overlapping sutures can be removed and adjusted with less overlay, and the reverse is also true in the case of too little deprojection. As opposed to primary cartilage resection and reattachment, overlapping the cartilaginous segment has been thought by some to diminish the risk of buckling or notching over time postoperatively. Kridel et al. in a retrospective review of 120 Figure 10: Sample nasal tip deprojection algorithm. Kridel et al. proposed analysis beginning with evaluation of

the radix. A full transfixion incision can be added to any of these procedures to allow further retrodisplacement. (Referenced from Soliemanzadeh P, Kridel RWH et al 2005).

patients posited that the medial crural overlay may obviate the need for a columellar strut, as opposed to an end to end anastomosis that may migrate or weaken over time.

When describing the alar setback technique, Foda noted that the sutured ends of the cartilage become fixed by surrounding fibrous tissue as opposed to having the two cartilage ends heal together. However, this may result in further loss of projection, pinching, alar notching, and even alar collapse. The medial overlay techniques have the advantages of overlap and splinting of cut ends to provide a more stable reconstruction that withstands the forces of healing. Note that in both deprojection maneuvers the lateral crura manipulation involves a cartilage overlay. The setback approach also uniquely allows one to control the relative length of infratip lobule vs columellar units based on degree of cartilage excision, as opposed to the medial crural overlay which relies on degree of overlap.

Rohrich et al. posited three most significant factors affecting tip projection: dorsal hump reduction, caudal septal reduction, and alar base resection.18 While unclear whether dissection and exposure of the cartilage in itself produces these effects, the authors developed the following algorithm to deproject the nasal tip:

- Open approach to the nose with full exposure of all cartilages.

- Intercartilaginous incision versus cephalic trim.

- Full dissection of medial crura and footplates.

- Anterior septal reduction with or without dorsal reduction or caudal trim as needed.

- Dissection of lateral crura and accessory cartilages.

- Division of the accessory cartilages of the lower lateral cartilage. Setback with cartilage overlay.

- Transection 2 mm posterior to the junction of the medial and intermediate crura, medial crural setback.

- Alar base resection as needed, as deprojecting the nasal tip will widen the alar base width.

- Membranous columella resection as needed

Rohrich et al. noted that maneuvers traditionally thought to dramatically reduce projection did not significantly do so, and thus authors advocated for more for sequential division of the soft tissue attachments of the lower lateral cartilage as opposed to cartilage division and/or overlay. But many other algorithms prioritize the cartilage resection and/or overlay technique as an initial maneuver after radix height is confirmed to be normal. Hence, the most optimal maneuvers to obtain adequate tip deprojection without compromising tip support are still being adequately defined.

References

- Foda HM et al. Arch Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2001 Nov;127(11):1341-6. Alar setback technique: a controlled method of nasal tip deprojection.

- Eisenberg I. A history of rhinoplasty. South African Medical Journal = Suid-afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 1982 Aug;62(9):286-292.

- Powell N, Humphreys B. Proportions of the Aesthetic Face. New York, NY: Thieme-Stratton; 1984: 23 Anderson JR. The dynamics of rhinoplasty. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress of Otolaryngology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Excerpta Medica; 1969

- Unger JG, Lee MR, Kwon RK, Rohrich RJ. A multivariate analysis of nasal tip deprojection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1163–1167.

- P Solomon, R Rival, a Mabini, J Boyd. Transfixion incision as an initial technique in nasal tip deprojection. Can J Plast Surg 2008;16(4):224-227.

- P Solomon, R Rival, a Mabini, J Boyd. Transfixion incision as an initial technique in nasal tip deprojection. Can J Plast Surg 2008;16(4):224-227.

- Lee MR, Geissler P, Cochran S, Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Decreasing nasal tip projection in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:41e–49e.

- Lee MR, Geissler P, Cochran S, Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Decreasing nasal tip projection in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:41e–49e.

- Kridel RW, Undavia SS. Deprojection of the nasal tip in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:440–446.

- Johnson CMJGodin MS The tension nose: open structure rhinoplasty approach. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995;9543- 45

- Kridel RW, Konior RJ. Controlled nasal tip rotation via the lateral crural overlay technique. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991; 117: 411-415

- Soliemanzadeh P, Kridel RW. Nasal tip overprojection: algorithm of surgical deprojection techniques and introduction of medial crural overlay. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005; 7: 374-380

- Foda, Hossam M. T. and Russell W. H. Kridel. “Lateral crural steal and lateral crural overlay: an objective evaluation.” Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery 125 12 (1999): 1365-70 .

- Deprojection of the Nasal Tip. www.rhinoplastycourse.nl. Published Jan 28, 2013

- Papel ID, Mabrie DC. Deprojecting the nasal profile. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1999;32:65–87.

- Rohrich et al. A Multivariate analysis of tip deprojection. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 129(5):1163–1167, May 2012.

- Robinson S, Thornton M. Nasal tip projection: nuances in understanding, assessment, and modification. Facial Plast Surg. 2012 Apr. 28(2):158-65.