Abstract

Special anatomic features determining both nasal aesthetics and function make middle vault surgery a challenging task for the rhinoplastic surgeon. Spreader grafts and spreader flaps, the split hump technique and the use of diced cartilage with fascia are some of the most common tools currently used for correction. The techniques described in this article enable not only treatment of middle vault deformities but also the prevention of rhinoplasty complications such as inverted-V deformity, hourglass deformity, dorsal saddling and nasal valve stenosis. In general, the golden rules in middle vault surgery are avoiding overresection and alteration of the mucosa, as well as reinforcing existing structures and rebuilding missing structures of the septum and the upper lateral cartilages.

Introduction

Middle vault correction is one of the most common surgical steps in rhinoplasty but also one of the most difficult since non-observance of the anatomy and certain surgical rules increase the risk of complications markedly. Dorsal saddling, inverted-V deformity, hourglass deformity or dorsal irregularities are some of the unpleasing results threatened in the early and late postoperative period. Therefore surgeon’s knowledge and understanding of nasal anatomy is the cornerstone for every rhinoplastic procedure.

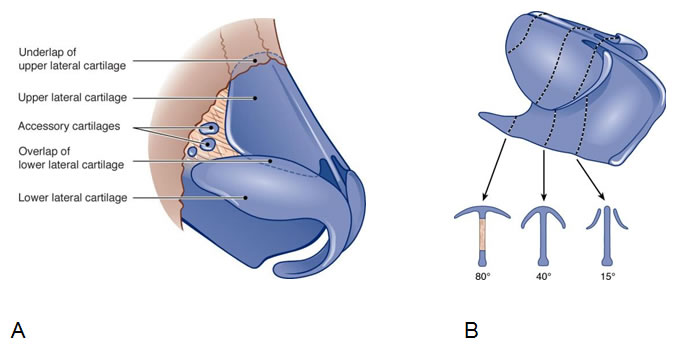

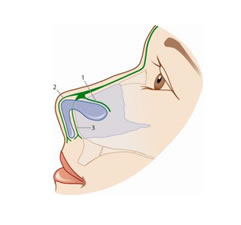

The middle vault represents the middle third of the nose consisting anatomically of the two upper lateral cartilages and the dorsal part of the nasal septum (Fig. 1A,B). The skin overlying the middle vault is thin, with the superficial areolar layer, the fibromuscular layer, the deep areolar layer, and the perichondral layer underneath. The fibromuscular layer represents the nasal superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) consisting of fibres of the levator labii alaeque nasi muscle and the transverse nasal muscle connected by the nasal aponeurosis. At its superior aspects the nasal SMAS extends to the frontal and procerus muscle in the glabella. Inferiorly it inserts in the nasal valve dividing in a deep (anterior to the septum) and superficial (over the lower lateral cartilage and the columella) layer (Fig. 2).

At the level of the osseo-cartilaginous framework, the cranial connection of the upper lateral cartilages (ULC) to the caudal margin of the nasal bones (K-area) including the underlap of the cartilage (Fig. 1A) is of great importance for the stability and support of the middle vault. This is also true for the tight T-shaped junction between the ULC and the septum and for attachments of the ULC to the lower lateral cartilages (LLC) in the scroll area. This zone lies between the ULC and LLC determining nasal valve function and tip support. The ULC commonly overlaps the lower lateral cartilage (Fig. 1A) but may show variations such as end to end, scrolling or opposite scrolling connection. It protrudes more or less into the vestibule forming the ‘cul de sac’. The most medial third of the caudal margin of the ULC is not attached to the septum but usually rotated upward 160 to 180 degrees acting as a free floppy segment which is essential for the dynamics of the inner nasal valve. Laterally, the ULC approaches the piriform aperture via the lateral soft tissue or ‘hinge’ area.

The caudal end of the middle vault is defined by the inner nasal valve area formed by the caudal edge of the ULC, the septum, the floor of the nasal cavity and laterally by the head of the inferior turbinates.

The inner valve having an angle of approximately 15° (Fig. 1B) and a cross- sectional area of 50 to 80 mm2, represents the narrowest part of the nasal passage, increasing the velocity of the inspired air according to the laws of fluid dynamics, the Hagen – Poiseuille equation and Bernoulli’s principle by up to 18 m/s. Traumas, surgical interventions, mucosal pathologies and anatomical deformities may be associated with a nasal valve stenosis, significantly impairing nasal breathing. On the other hand, an extensive widening of the nasal valve area causes airstream turbulence which finally compromises nasal air conditioning. Therefore, the middle vault plays not only an important role in the nasal appearance but also in the nasal function.

Deformities And Diagnosis

The first step of preoperative planning is to understand the patient’s individual pathology and gain information about nasal function. Examination should start with the observation of the outer appearance of the nose including judgement of skin quality, which is important for both healing and anticipated surgical outcome. Ethnic groups should be also taken into consideration. The Lancer Ethnicity Scale (LES) in combination with the Fitzpatrick Skin Phototype System deliver useful information about pre- and postoperative patient counselling. A proportional nasal and facial analysis should be made, based on the assessment of the nasal dorsum width, the bony and cartilaginous projection, the supratip region, the pyramidal width, the existence of a bony and cartilaginous hump, and crooked or saddle nose deformities. For the classification of the nasal dorsal deformities the surgeon can also use the Kienstra-Sherris-Kern (KSK) grading system. Observation of the nose while at rest, and during normal and forced inspiration reveals the tendency for an alar collapse which is common in nasal valve stenosis. Visual analysis of the outer nasal shape is followed by palpation of the nasal framework providing information about stability, elasticity and any kind of irregularities. The proportions of bone and cartilage as well as the strength and resilience of the ULC, especially, are of major importance. Short bones and weak ULCs are predisposed to develop an inverted-V (Fig. 5A) or hourglass deformity (Fig. 3A), which are often seen after dorsal overresection and missing middle vault reinforcement, resulting by the posterior displacement of the nasal bones and the upper lateral cartilages.

Assessment of inner nose pathologies like chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), septal deviations, hyperplasia of the turbinates and valve stenosis principally is performed by endonasal endoscopy. This can be done with a flexible, a 0° or a 30° angled endoscope. Predominantly in revisional cases the use of a cotton bulb to investigate strength and flexibility of the septum is helpful.

Most difficult to detect are nasal valve stenosis pathologies. Whereas a static valve stenosis may be diagnosed only by nasal endoscopy and external view, a dynamic valve stenosis requires the patient to gently and then strongly inspirate. Cottle`s maneuver and the cotton ball test placing small cotton balls into the inner valve, may also be used for evaluation. A documentation of the nasal function with rhinomanometry or acoustic rhinometry is recommended prior to surgery at least for medicolegal reasons. A CT-scan is not needed for most middle vault deformities but a preoperative computer simulation is favoured by the authors. During the simulation the patient is informed about nasal anatomy, surgical techniques and possible, realistic surgical outcomes.

Surgical Techniques

Dealing with middle vault pathologies may be demanding for the rhinoplastic surgeon and is aimed at a harmonious aesthetic result with a physiologic nasal function. The correction techniques that have been widely accepted and presented in the literature include grafting, suturing techniques and the use of various transplants or implants like fillers or fascia. The donor site for grafting is chosen according to the underlying pathology and should be as atraumatic for the patient as possible. These sites include the nasal septum, the pinna (cavum or cymba conchae, tragus), the rib or a combination of all.

The Spreader technique

Spreader grafts, mostly taken from the septum, are the workhorse in middle vault surgery by correcting the lack of dorsal support to lateral walls, and reconstructing the dorsal profile and valve area. Most surgeons prefer an external approach as it allows better visualization and precise graft positioning but spreader grafts can be also placed with an endonasal approach. The grafts were first described in 1984 by JH Sheen and may be positioned unilaterally (Fig. 6) or bilaterally (Fig. 3) between the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal septum.

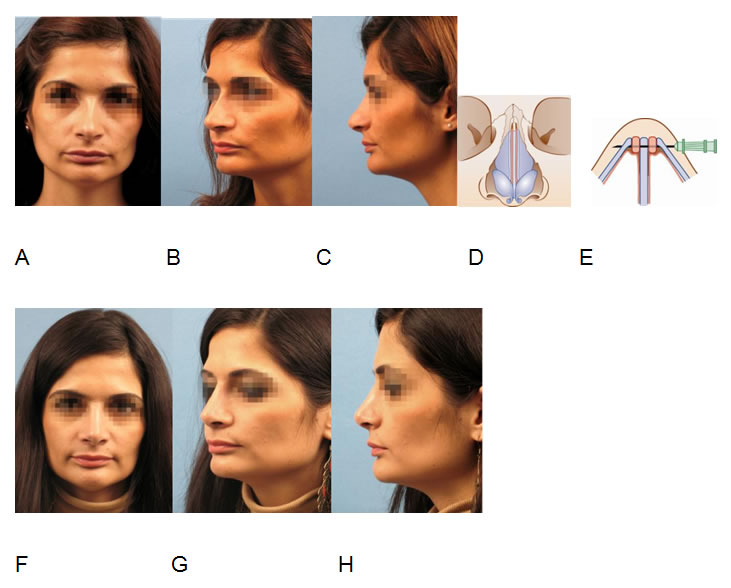

The preferably trapezoid shaped grafts may be fixed temporally with a 27-gauge needle and sutured to the upper septum using a long-acting monofilament absorbable or a nonabsorbable suture (5/0). In this way they give support to the middle third of the nose correcting as well as preventing pathologies such as the hourglass (Fig. 3A) and inverted-V deformity (Fig. 5A) or dorsal deviations.

Oneal and Berkowitz, later on Byrd, Gruber and others modified the classical free spreader graft technique by folding the upper portion of the ULC inward and mattress-suturing the bent cartilage to the dorsal septum after the inner mucoperichondrium has been detached, called autospreader flap or simply spreader flap (Fig. 4D,E). Gentle squeezing with Adson forceps or incisions at the apex of the bent cartilage may alleviate inward folding when cartilage resilience is high. Limitations of autospreader flaps are dorsal irregularities and deviations with strong underlying tractive forces, as well as revisional cases characterized by dorsal scarring and trimmed ULC.

Correction of an hourglass deformity (A,B,C) with inner nasal valve stenosis after previous hump resection using bilateral spreader grafts (D,E) inserted via open rhinoplasty. Postoperative result after 1,5 years (F,G,H).

Nasal valve surgery

Spreader grafts (Fig. 3D,E), spreader flaps (Fig. 4D,E) and the minispreader flap technique, which rotates and suspends resected cephalic parts of the LLC to the dorsum all have been found to be effective in the prevention and treatment of inner nasal valve stenosis by increasing the valve angle. Nevertheless, in revisional surgery after overresection of cartilage and mucosa in the scroll area, other reconstructive techniques may be required. Guyuron reported on an upper lateral splay graft inserted underneath the caudal portion of the ULCs, Clark and Cook on the use of a conchal cartilage butterfly graft sutured to the outer surface of the ULC. Other commonly used valve widening options are lateral crural strut grafts, flaring sutures placed between both lateral aspects of the ULCs, M-plasties resecting small parts of the caudal end of the ULC followed by a M-shaped closure of the mucosa and intranasally performed Z-plasties lateralizing and lengthening the scroll region. The valve opening effect may be supported by suspension sutures running from the caudal/lateral part of the ULC to the periosteum of the piriform aperture or orbital rim.

Dorsal reduction

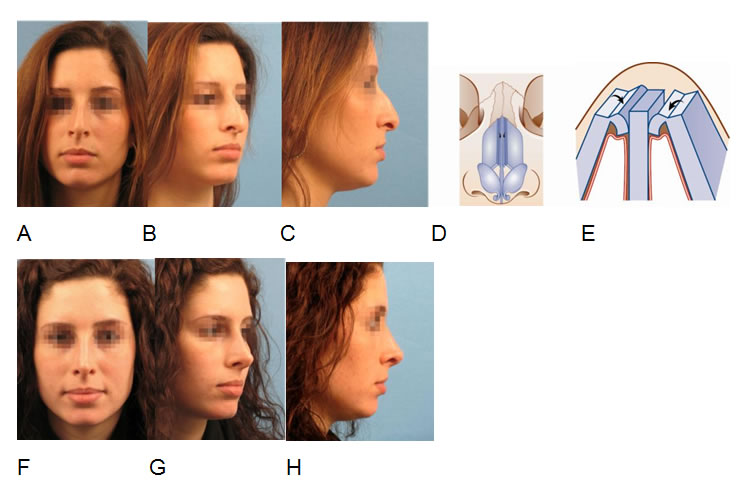

The majority of patients who consult rhinoplasty surgeons seek reduction rhinoplasty. Hump removal is one of the most common procedures, playing an enormous role in patient’s judgement of a good surgical result. Preoperatively hump reduction techniques may be demonstrated to the patient with the help of drawings or computer programmes enabling the simulation of a straight dorsum as well as an under- or overresected middle vault. Furthermore, patients showing a pseudo-hump learn that this deformity is not treated with reduction rhinoplasty but with the increase of tip-projection. The standard technique for hump removal is determined by the degree and location of dorsal overprojection which can be cartilaginous, bony or most commonly a combination of both. The goal of a hump resection is to remove excess cartilage and bone from the nasal dorsum avoiding overresection and complications like inverted-V or saddle nose deformity. In general, dorsal reduction can be done en bloc with scalpel and chisel, removing the cartilaginous and bony hump as one piece, or in a two – step procedure by splitting the upper lateral cartilages of the septum, then resecting the cartilaginous dorsum and the bony hump separately. This split hump technique procedure enables the preservation of the upper lateral cartilage and is most suitable for proper reconstruction of the nasal dorsum using spreader grafts or spreader flaps (Fig. 4A-H). Prior to any kind of hump resection, the decollement should by performed subperichondrially at the cartilaginous dorsum and subperiosteally over the nasal bones. Except in rasping procedures, the mucosa has to be detached from the under surface of the ULCs up to the nasal bone in order to prevent mucosal disruption which could end up in postoperative scarring, middle vault collapse and inner valve incompetence. The degree of undermining varies individually and depends on the nasal hump`s extension. This is also true for hump resection. As a rule cartilaginous humps are removed using 11 or 15 blades, bony humps using rasps, osteotomes, chisels or burs.

Rasps, burs or shavers are best suited for small bony humps or irregularities, osteotomes or chisels for more marked osseous hump formations.

Having performed hump resection the surgeon has to deal with an open roof in most cases. In general, lateral, superior and paramedian oblique osteotomies are performed for closure, preferably via the percutaneous way. Only in more cephalad located open roof deformities are doorangle- like lateral, superior and straigtht paramedian osteotomies preferred by the authors. Additional intermediate osteotomies may be necessary in a crooked nose or in other bony irregularities. At the end of surgery the nasal dorsum should be carefully palpated with a wet fingertip, since even minor invisible irregularities could trigger the patient’s dissatisfaction. The use of autogenous temporal fascia or homologous fascia lata over the nasal dorsum after hump resection is helpful in diminishing minor dorsal irregularities.

Open rhinoplasty for correction of a nasal hump and a downward rotated, underprojected tip (A,B,C). Split hump technique for dorsal reduction, spreader flaps (D,E) for dorsal reconstruction and lateral sliding technique for tip refinement. Postoperative result after 6 month (F,G,H).

Dorsal augmentation

Surgical techniques in dorsal deficiencies aim at the restoration of a stable structural support of the dorsum as well as a functioning valve area. Only in minor deficiencies optical camouflage may be the main focus. The choice for the appropriate procedure depends on various parameters. Shape and degree of a dorsal deficiency, and the correlation to other facial structures and skin quality are just as important considerations as previous surgery, availability of graft material, surgeon´s experience, and patient´s wishes. As a rule of thumb dorsal augmentation is indicated when the dorsal line lies not at or slightly (up to 2 mm) posterior to a line drawn from the nasion to the tip, but significantly posterior, an adequate tip projection provided. From the functional perspective, dorsal deficiencies are often combined with inner nasal valve stenosis. This may also be evident in a narrow nasal dorsum which needs augmentation not in a vertical but horizontal dimension (Fig. 3).

Septoplasty, extracorporeal septum reconstruction, spreader grafts and spreader flaps are basic procedures in middle vault reconstruction increasing dorsal septal support. Combined with dorsal onlay grafts, pleasing aesthetic results may be achieved. To prevent irregularities and step-offs in the transition zone to the nasal bone and the nasal tip, it is advisable not only to fill the zone of dorsal deficiency but to insert longer grafts from the nasion to the nasal tip. This requires the alignment of the whole nasal dorsum with a straight dorsal line in advance.

Focussing on dorsal onlay grafts, there is a myriad of publications in the literature, ranging from autologous septal, conchal and rib cartilage, split calvarian and iliac crest bone, homologous fascia lata, acellular allogeneic human cadaver dermis (AlloDermâ), irradiated cartilage up to alloplastic grafts such as polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex), silicone (Silastic), porous polyethylene (Medpor, Plastipore), polyester and polyamide (Dacron, Mersilene, Supramid), hydroxyapatite and ivory. In any case autologous material should be preferred because of its low risk of infection and extrusion. Nevertheless even autologous cartilage may be critical when inserted as a trimmed, crushed, morselized or bruised graft because of the resorption rate of up to 30-60% within the first 12 months and threatening unpredictable changes. Following findings of Daniel and Carter the authors favor diced cartilage grafts with fascia in the majority of cases. Wrapped in a sheet of deep temporal fascia or homologous fascia lata, diced cartilage either from the septum (Fig. 5A-E), the concha or the rib can be used for 3-10mm dorsal augmentation. For deficiencies less than 3 mm, one or two layers of fascia with or without underlying thinned cartilage suffice. For deficiencies more than 1-1,5cm the core of osteocartilaginous rib grafts is recommended in most cases. Although not providing structural support, diced cartilage wrapped with fascia shows many advantages such as simple fabrication, flexibility, options for adjustment even within the first 1-2 weeks after surgery, none or little resorption, and no risk for rejection or postoperative changes like warping or foreign body reaction.

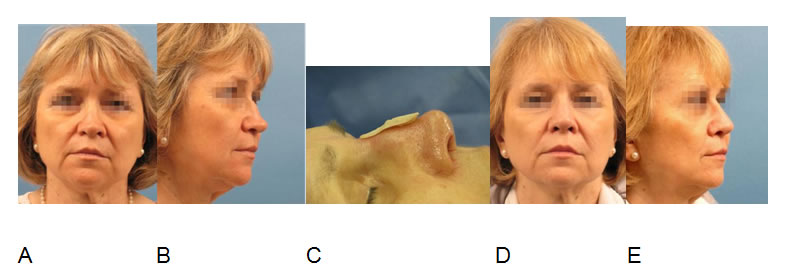

Correction of a saddle nose and inverted-V deformity (A,B) via open extracorporeal septal reconstruction, bilateral free spreader grafts and diced septal cartilage wrapped in temporal fascia (C). Result after 1 year (D,E).

Even using homologous fascia lata the risk for infection and noticeable structural changes is negligible according to the author’s experience. Therefore using diced cartilage fascia grafts, no overcorrection should be gone for. All grafts may be inserted endonasally after preparation of a supraperichondrial and subperiosteal pocket.

However, in severe deformities, secondary cases, and when further reconstruction of the nasal framework is needed, an external approach has been found to be superior.

Dorsal deviations

Correction of dorsal deviations and asymmetric irregularities is another difficult task since it is not confined to the middle vault in the majority of cases. Either congenital or caused by trauma or previous surgery, the adjacent bony pyramid and nasal tip are mostly involved in influencing the surgical planning. The principles of treatment and prevention of dorsal deviations are alike as they concentrate on the fabrication of a straight septum and the correct position of the bony and cartilaginous framework.

Accurate osteotomies, the proper use and fixation of unilateral (Fig. 6A-E) or bilateral spreader grafts and onlay grafting flank the basic procedure of straightening the cartilaginous and osseous septum. First and foremost in traumatic irregularities the surgical procedure might have to be modified intraoperatively instead of performing profound preoperative analysis and planning. Therefore it is advisable to comprehensively inform the patient and obtain an extense informed consent prior to surgery.

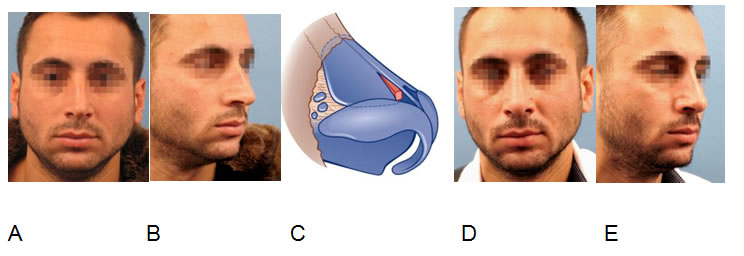

Crooked nose correction (A,B,C) performing septoplasty and dexter unilateral spreader graft insertion (D) via closed approach. Result after 2 years (D,E).

Discussion

Respecting the aforementioned rules for middle vault surgery makes the rate of complications low. The most common complication, the inverted-V deformity, can be avoided by the prevention of an overresection in hump removals, the preservation of the mucosa between the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal septum and highlighting the principles of spreader grafts and spreader flaps for dorsal reconstruction. These rules also count for the correction of hourglass deformities, nasal valve stenosis and even saddle nose deformities. They all may result from an overresection of the nasal dorsum with alteration of the septolateral cartilage and insufficient structural restitution of the dorsum. Even if overresection has been found to be one of the major surgical faults, underresection has also to be avoided as it can lead to unpleasing results such as polly beak deformity after hump resection. The judgment as to when to stop and how far to go requires profound anatomical knowledge, lengthy training, surgical experience and the critical personal follow up of all patients. Though some surgeons almost exclusively recommend the endonasal approach the authors strongly suggest the open approach for most middle vault procedures except for small procedures as hump rasping, reduction of a moderate cartilaginous and osseous overprojection, camouflaging dorsal deficiencies with fascia and cartilage or correction of a moderate crooked nose by an unilateral spreader graft. The complexity of the anatomy, especially in the transition zone to the bone (K-area) and the LLC (scroll area), as well as the need for proper analysis and accurate correction often calls for a surgical procedure under direct view. Whereas the principle of less resection, more reinforcement and reconstruction is generally accepted, the various options of graft material are still under discussion. The authors favor the use of autogenous cartilage, autogenous temporal fascia or homologous fascia lata, and the technique of diced cartilage wrapped in fascia for dorsal augmentation. Rib cartilage should be reserved for severe dorsal deficiencies, hyaluronic acid filler for the camouflage of minor irregularities. The use of engineered cartilage grafts has been discussed in the last decades and is certainly one of the most promising grafting types in the future.

References

- Koppe T, Giotakis EI, Heppt W. Functional Anatomy of the nose. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27:135–145.

- Toriumi DM, Mueller RA, Grosch T, et al. Vascular anatomy of the nose and the external rhinoplasty approach. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122 (1):24-34.

- Saban Y, Amodeo CA, Hammou JC, Polselli R. An anatomical study of the nasal superficial musculoaponeurotic system. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2008;10(2):109-115.

- Cunningham B, McKinney P. The alar scroll: An important anatomical structure in lobule surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:1591-99.

- Sutera SP, Skalak R. The history of Poiseuille’s law. Annual review of fluid mechanics. 1993; Vol. 25:1-19.

- asperbauer JL, Kern EB. Nasal valve physiology. Implications in nasal surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1987;20:699-719.

- Orten S, Hilger P. Facial analysis of the rhinoplasty patient. In: Papel ID, editor. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Thieme 2002; 361–368.

- Talakoub L, Wesley NO. Differences in perceptions of beauty and cosmetic procedures performed in ethnic patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg, Elsevier 2009;28:115-129.

- Kienstra MA, Gassner H, Sherris DA, Kern EB. A Grading system for nasal dorsal deformities. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003;5:138-143.

- Daniel RK, Brenner KA. Saddle nose deformity: A new classification and treatment. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2006;14(4):301-312.

- Sykes JM, Tapias V, Kim JE. Management of the nasal dorsum. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27(2):192-202.

- Heppt W, Gubisch W. Septal surgery in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27(2):167-78.

- Apaydin F. Nasal Valve Surgery. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27:179–191.

- Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;73(2):230-9.

- Rohrich RJ, Hollier LH. Use of spreader grafts in the external approach to rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg 1996;23(2):255-62.

- Oneal RM, Berkowitz RL. Upper lateral cartilage spreader flaps in rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J 1998;18:370-371.

- amirand A, Doucet J, Harris J. Nose surgery: how to prevent a middle vault collapse – a review of 50 patients 3 to 21 years after surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114(2):527-34.

- Byrd HS, Meade RA, Gonyon DL Jr. Using the autospreader flap in primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(6):1897-902.

- Gruber RP, Park E, Newman J, Berkowitz L, Oneal R. The spreader flap in primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119(6):1903-10.

- Ozmen S, Ayhan S, Findikcioglu K, Kandal S, Atabay K. Upper lateral cartilage fold-in flap: a combined spreader and/or splay graft effect without cartilage grafts. Ann Plast Surg 2008;61(5):527-32.

- Guyuron B, Michelow BJ, Englebardt C. Upper lateral splay graft. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998; 102(6):2169-77.

- Clark JM, Cook TA. The ‘Butterfly’ Graft in functional secondary Rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 2002;112:1917-1925.

- Park S. The flaring suture to augment the repair of the dysfunctional nasal valve. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101(4):1120-2.

- Menger DJ. Lateral crus pull-up: a method for collapse of the external nasal valve. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2006;8(5):333-7.

- Rohrich R, Muzaffar A, Janis J. Component dorsal hump reduction: the importance of maintaining dorsal aesthetic lines in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;114(5):1298- 308.

- Huizing EH, de Groot J. Functional reconstructive nasal surgery. Thieme 2003.

- Park S, Day T, Farrior E et al. Facial plastic surgery, the essential guide. Thieme 2005.

- Becker D, Park S. Revision Rhinoplasty. Thieme 2008.

- Daniel RK. Mastering Rhinoplasty. Springer 2010.

- Prendiville S, Zimbler M, Kokoska M, Thomas J. Middle-vault narrowing in the wide nasal dorsum: the “Reverse Spreader” technique. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2002;4(1):52-5.

- Erol O. The Turkish delight: A pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:2229-2234.

- Daniel R, Calvert J. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004;113:2156–2171.

- Daniel R. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery: current techniques and applications. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;122:1883-1889.

- Ahn J, Honrado C, Horn C. Combined silicone and cartilage implants: augmentation rhinoplasty in Asian patients. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(2):120-3.

- Fanous N, Samaha M, Yoskovitch A. Dacron implants in rhinoplasty: a review of 136 cases of tip and dorsum implants. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2002;4(3):149-56.

- Dresner H, Hilger P. An overview of nasal dorsal augmentation. Semin Plast Surg 2008; 22(2): 65–73.

- Mendelsohn M. Straightening the crooked middle third of the nose: using porous polyethylene extended spreader grafts. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2005 7(2):74-80.

- Shipchandler TZ, Papel ID. The crooked nose. Facial Plast Surg 2011;27(2):203-12