Abstract

Spreader grafts are an essential tool in the armamentarium of the rhinoplasty surgeon. Spreader grafts provide support of the middle vault and widen the internal nasal valve, the narrowest portion of the nasal airway which contributes approximately half of the total airway resistance. Spreader grafts are frequently indicated in functional rhinoplasty and in revision rhinoplasty when middle vault collapse is encountered. Also, spreader grafts may be employed during primary cosmetic rhinoplasty in selected situations. Classically, the “high-risk” patient has a narrow middle vault, short nasal bones paired with long upper lateral cartilages, or weak cartilaginous support. Broader indications have also been advocated. Placement of spreader grafts can be performed in traditional external rhinoplasty (open) or via endonasal (closed) approaches. In this article we will review patient selection, physical examination, procedure details, complications, and outcome assessment. Lastly, two illustrative cases of the senior author will be presented.

Indications and Patient Selection

Spreader grafts may be used to address congenital, traumatic, or iatrogenic deformities of the internal nasal valve (INV) and middle vault. This technique is used most commonly in functional rhinoplasty, for patients with middle vault and nasal valve collapse, and in revision rhinoplasty when the primary surgery has resulted in narrowing or collapse of the middle vault. Placement of spreader grafts may be proactive or preventative as well, as in primary cosmetic rhinoplasty when the support of the middle vault is felt to be compromised. The particular characteristics and physical exam findings of this group will be discussed below, after a review of the relevant nasal anatomy and physiology.

Internal Valve Obstruction and Inspiratory Collapse

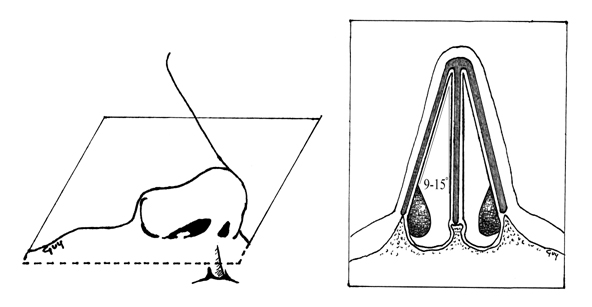

For proper and comfortable nasal respiration, a degree of resistance to airflow must be produced by the intranasal structures. Parodoxically, absence of adequate resistance gives a feeling of nasal obstruction. This is demonstrated in the extreme case of atrophic rhinitis, where an overly wide or “empty” nasal airway has been created by complete turbinectomy, with the resulting loss of the sensation of airflow creating an impression of near total blockage. In the nasal passage, resistance and laminar flow are produced by the turbinates and the INV. Specifically, the INV refers to the cross-sectional area bordered by the junction of the caudal portion of the upper lateral cartilage (ULC) and the nasal septum, circumscribing an angle of 9 to 15 degrees in the normal Caucasian nose (FIGURE 1) [Tardy, 1990].

This configuration meets the anatomical definition of a valve, in that it is a movable structure that regulates the flow of gas or fluid. Anatomically, the INV is bounded by the head of the inferior turbinate and the pyriform aperture laterally, the septum medially, the junction of the ULC with the lower lateral cartilage (LLC) and septum superiorly, and the floor of the nose inferiorly (Figure 1) This space is sometimes referred to as the nasal valve area [Becker, Revision Rhinoplasty].

The INV significantly regulates nasal airflow and resistance, as well as the velocity and shape of the air stream. Inspired air currents are modified from a column to a sheet of air by the shape and current condition of the nasal valve area structures. The INV is the major flow-resistive segment of the airway, contributing about half of all resistance [Cole, 2003].

Measurements made from nasal casts and calculated from rhinomanometry indicate an average area of 0.73 cubic centimeters for the adult INV [McCaffrey, 1990]. During respiration, negative inspiratory pressure is transmitted from the nasopharynx to the valve area, which then actively narrows. Obstruction, an overly acute angle, or excess rigidity of the INV result in the sensation of nasal airway blockade.

A common indication for spreader graft placement is the treatment of INV obstruction or structural weakness. This may be congenital or traumatic in rare cases, but is more often a complication of previous nasal surgery – particularly previous rhinoplasty. Even very small narrowing changes in the anatomical arrangement of the INV may have a significant effect on air flow, as dictated by Poiseuille’s Law, which states that flow is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the radius of a passageway.

At times, scarring and/or contracture of the soft tissues at the INV may occur secondary to incisions made in the scroll region (articulation of ULC and LLC) as in a cephalic trim, particularly with the endonasal rhinoplasty approach [Joe, 2004; Beekhuis, 1976]. In addition, violation of the nasal mucosa at the junction of the ULC and the superior dorsal septum may contribute to scarring in this area. This may accompany high septoplasty with submucous resection or surgical reduction of the nasal dorsum [Toriumi, 1995]. Meticulous dissection may reduce this risk. Still, these sequelae may occur despite well performed surgery. Regardless of etiology, formation of mucosal synechiae in the superior part of the INV reduces its area and thus significantly reduces airflow [Constantinides, 1996; Beekhuis, 1976].

Inspiratory collapse at the INV may occur in patients with a narrow INV area at rest or in patients with thin and weak ULC. In the former case, the Bernoulli principle dictates that areas of high airflow result in negative pressures at the periphery of the airstream. This pressure differential may result in medial movement of the ULC. In patients where the INV angle is overly acute at baseline, this medial movement can functionally obliterate a significant portion of the cross-sectional area of the nasal airway. In the latter case, even where the INV angle is normal, the transmitted negative pressure from the nasopharynx during inspiration overcomes the static forces of the relatively weak cartilaginous nasal support. This leads to dynamic obstruction of inspiratory airflow.

Middle Vault Collapse

The middle vault is the three dimensional portion of the nasal passageway where the ULC meet the quadrangular cartilage and lies just interior to the INV. The roof of the middle vault is formed by the ULC and extends from the INV anteriorly to the junction of the nasal bones and ULC posteriorly. Middle vault collapse occurs when there is a significant deficit in the septal support of the ULC. This may accompany nasal trauma, such as septal fracture, or as a late complication of an undiagnosed septal hematoma. Infectious etiologies are possible as well, such as septal abscess with dissolution of the quadrangular cartilage. Rare inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, may lead to a similar deficiency in vertical support mechanisms and result in middle vault collapse or a saddle nose deformity.

Collapse of the middle vault is a known potential complication of rhinoplasty, occurring when the ULC fall downward and inward toward the septum. Iatrogenic middle vault collapse may occur after hump reduction when support of the ULCs is inadequate [Joe, 2004]. The disarticulation of the ULC and septal cartilage may result in instability of the remnant ULC medially, and adding osteotomies can further destabilize the ULC laterally [Tardy, 1990; Spielmann, 2009].

Analogous to the detrimental effects of mucosal injury at the INV, tears in the middle vault mucosa may contribute significantly to middle vault collapse. Healing forces in the middle vault create additional downward force on the cartilaginous framework. The result is both a significant cosmetic issue, the inverted V-deformity, and significant nasal airway obstruction. (FIGURE 2)

Evaluation of the Patient with Nasal Obstruction

A complete external and internal nasal examination must be undertaken before considering any specific treatment in a patient presenting with nasal obstruction. A detailed description of this can be found elsewhere (Becker/Toriumi, Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual). With regard to nasal valve collapse, the physician should take particular note of the width of the nasal dorsum, the length of the nasal bones, the flare of the nasal alae, and the degree of intrinsic support at the tip. Further information is obtained by having the patient breath normally and then in an exaggerated manner. This dynamic external nasal exam may reveal alar collapse or supra-alar pinching on inspiration, alerting the surgeon to possible nasal valve issues. In appropriate patients, the facial nerve function should also be assessed to look for any asymmetry in facial musculature or collapse of the ENV from nasalis or dilator nasi muscle paresis.

With regard to the internal nasal examination, anterior rhinoscopy should be performed. This maneuver is performed with a headlight and a short, blunt-nosed nasal speculum and allows visualization the nasal sill, caudal septum, inferior turbinates, and ENV. This view is generally limited to the anterior nasal airway, however, and more posterior pathology requires more advanced modalities (discussed below). If an allergic component to the nasal obstruction is suspected, examination should be performed before and after application of topical decongestant. Significant improvement in airflow from decongestant spray alone may indicate inferior turbinate hypertrophy and mucosal edema. This should prompt further investigation of allergies as a contributor to nasal airway issues.

The Cottle maneuver may then be performed. This is an extremely informative part of the physical exam, allowing assessment of the INV. [Chandra, 2009] The classical description of this maneuver involves the surgeon retracting the cheek skin and lateral nostril, which pulls the ULC away from the septum in order to widen this angle and temporarily create a larger nasal valve area. [Lee, 2009; Chandra, 2009; Becker, 2009] Unfortunately, the surgeon may create false-positive results with this test unless the lateralization of the nasal structures is performed realistically (on the order of a few millimeters). Many surgeons use a modification of the Cottle maneuver. This involves placing a small ear curette or similar device under the LLC and then ULC, both before and after decongestion and topical anesthesia. Airway patency on each side of the nasal passage is assessed with the curette gently elevating these cartilages, one at a time, in order to recreate the experience of having these areas reinforced or widened with grafting techniques. [Constantinides, 2002] Nasal airflow improvement with ULC support suggests INV pathology, while improvement with LLC support suggests an ENV etiology. [Lee, 2009; Constantinides, 2002]

It is advisable to perform a diagnostic nasal endoscopy following initial anterior rhinoscopy. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy allows a thorough examination of the nasal airway posterior to the head of the inferior turbinate. Endoscopy, whether flexible or rigid, should include evaluation of the septum, nasal mucosa, inferior and middle turbinates, INV, and middle meatus. Unexpected pathology may necessitate further workup, as described by Lanfranchi, et al. [Lanfranchi, 2004] According to this study, additional surgical therapy to relieve nasal obstruction was undertaken in 28 of 95 (29%) patients because of the nasal endoscopy findings. The senior author has found this to be a critical portion of the preoperative assessment, as it may assist in the diagnosis of significant nasal pathology which would not otherwise be addressed in rhinoplasty, such as sinonasal polyps, enlarged middle turbinates, and even benign tumors in rare cases. Again, assessment before and after topical decongestion is advised, as improvement or relief of airway obstruction after the administration of a decongestant alone may point to an allergic or sinonasal mucosal inflammatory disorder. [Corey, 1997]

Radiologic studies may be employed when the site or source of nasal obstruction cannot be definitively identified with a thorough history and physical exam. In these cases, a coronal sinus CT scan can assist in identifying sources of nasal obstruction, like a concha bullosa or posterior septal deviation, which may not have been fully appreciated on physical exam or endoscopy. Additionally, CT may provide useful information for a patient who has had a history of chronic nasal obstruction or sinonasal inflammatory disease. This could further alert the surgeon to pathology that must be addressed prior to or at the time of rhinoplasty, leading to an alteration of the surgical plan or postoperative management. [Chandra, 2009; Becker, 2009]

In extreme cases, further quantitative investigation of nasal airway pathology may be indicated. Available measures include rhinomanometry and acoustic rhinometry. The rhinomanometer is a device that functionally measures nasal airflow at a fixed pressure differential during the nasal respiratory cycle. With this technique, a pressure-flow curve is generated which demonstrates higher nasal resistance and less nasal airflow in a more obstructed nose. Acoustic rhinometry works by propagating a sound wave through the nasal cavity, which is reflected back to create a two-dimensional representation of the nasal airway [Lal, 2004]. Acoustic rhinometry is a complementary study to rhinomanometry, in that it assists in measuring the location of the nasal obstruction, not total nasal resistance. Interestingly, acoustic rhinometry has been deemed the most accurate measurement of nasal area, especially anterior in the nose and the region of the nasal valve [Cakmak, 2003]. Perhaps for this reason, acoustic rhinometry is the most utilized method of measuring nasal airway patency in both clinical and research settings [Chandra, 2009].

Spreader Grafts in Rhinoplasty – External and Endonasal Approaches to the Middle Nasal Vault

Modern rhinoplasty techniques increasingly emphasize preservation of cartilaginous and bony substructure. This is of particular importance in the middle nasal vault, as preservation of support for the upper lateral cartilages helps to avoid collapse of the middle vault and the associated internal nasal valve. Middle vault and nasal valve collapse can cause overnarrowing of the middle third of the nose, with the “inverted V” deformity and nasal obstruction. When support and contour of the middle vault require reconstitution, spreader grafts can be used.

Use of spreader grafts in primary rhinoplasty is becoming much more common.10, 17-18 Spreader grafts can be effective in maintaining the contour of the middle vaults after hump reduction. While it may be technically easier to place spreader grafts via an external approach, spreader grafts can be placed via the endonasal or the external(open) approach.6,9-10,19-20

Narrowing of the middle nasal vault that occurs when the T configuration of the nasal septum is resected with dorsal hump removal may be problematic in the high risk patient.10 Spreader grafts act as a spacer between the upper lateral cartilage and septum, preventing excessive narrowing in the high risk patient or correcting an over-narrow middle vault when it exists.

As described by Sheen19, a submucoperichondrial tunnel on one or both sides of the dorsal aspect of the septum may be prepared by elevating the mucoperichondrium bridging the upper lateral cartilages to the septum. This dissection provides a space to be filled by a cartilage strip insinuated and secured by suture-fixation into the pocket, lateralizing the upper lateral cartilage(s), improving the airway and effectively maintaining the width, or widening when indicated, the appearance of the middle third of the nose.

Spreader grafts may be comfortably carried out through traditional, less invasive endonasal techniques. In more complex reconstructions, particularly complicated by multiple abnormalities, an external rhinoplasty approach may facilitate accurate dissection and graft suture fixation. Some surgeons find that the external approach is simply a technically easier method to undertake spreader graft placement.

It should be noted that the use of the external rhinoplasty approach may lead to a greater need for spreader grafts to preserve the nasal valve and middle nasal width, which may put at risk due to the loss of support to the upper lateral cartilages caused by more extensive skin undermining. Proponents of the endonasal approach to rhinoplasty describe the importance of preserving the middle vault mucosa. The intact middle vault mucosa is said to act as a “mucosal spreader graft” that supports the upper lateral cartilages and mitigates against the risk of nasal valve collapse.

Identifying the high risk patient during initial preoperative analysis is essential to the prevention of excessive narrowing of the middle nasal vault with internal nasal valve collapse.10 Sheen19 identified an anatomical variant that he labelled the “narrow nose syndrome.” Short nasal bones, long weak upper lateral cartilages, thin skin, and a narrow projecting nose predispose to middle vault collapse.9-10 As described by Toriumi10, commonly performed surgical maneuvers can result in loss of support to the middle vault. A large en bloc hump removal should be avoided, as the T-shaped support of the nasal septum is eliminated and the intranasal mucosa (which provides important support to the upper lateral cartilage) is at risk of injury. Cephalic trim (volume reduction) of the lateral crura disrupts the scroll (recurvature) and frees the caudal margin of the upper lateral cartilage. Lateral osteotomies may further medialize the upper lateral cartilages. The upper lateral cartilages can fall toward the narrowed dorsal septal edge, producing middle vault and internal valvular collapse.10 Collapse of the middle vault may highlight the caudal edges of the nasal bones to produce the characteristic “inverted V” deformity.10,19

In the majority of patients the combination of these maneuvers will not result in a problem; however, in high risk patients this combination of maneuvers may contribute to excessive narrowing of the middle vault with internal valve collapse.

Experience is required to develop reliable surgical judgment regarding the appropriate use of spreader grafts. In this regard, Perkins29 describes an evolution in his personal philosophy that reflects some of the issues involved in the decision making process, and provides valuable insight into the evolution in the decision making that has occurred over the last 15-20 years. While the concept of a graduated approach to achieve a pleasing aesthetic result has been foremost in his personal philosophy, the evolving need to achieve more refined results and prevent late complications has resulted in his increased use of spreader grafts. Perkins continues to strongly advocate the philosophy that the approach selected should provide the least intervention in the shortest time to achieve a satisfactory result and satisfy the patient’s goals. However, his choice of approach has changed due to late complications that he has seen occur. The 2 areas that he found most commonly cause late complications in rhinoplasty are the midnasal pyramid and lateral alar sidewalls. Paramount to provide a structural foundation for the middle vault (ie spreader grafts). While issues such as these can be addressed using the endonasal approach, it is sometimes far easier to place structural grafts via the external approach. Perkins reports that he uses spreader grafts with increasing frequency in primary rhinoplasty after hump reduction, based on his extended long-term followup.

Cosmetic Indications for Spreader Grafts

As described above, spreader grafts are also useful in certain primary cosmetic rhinoplasty patients after hump removal. Other cosmetic indications for spreader grafts include widening of the nasal dorsum in patients with a narrow middle vault, straightening of a twisted nose, and nasal lengthening in patients with a short nose. [Boccieri, 2005; Palacin, 2007]

Maintaining or widening of the middle nasal vault and INV to improve nasal airflow is the original raison d’etre of the spreader graft technique, but overwidening must be avoided as this can be aesthetically unpleasing. In certain cases, however, widening of the nasal dorsum can be an aesthetically pleasing maneuver. In a patient with an overly thin middle vault, spreader grafts may be applied to achieve a favorable aesthetic balance. [Becker Revision Rhinoplasty].

Spreader grafts can be an invaluable tool in the correction of the twisted nose. By carving grafts to fit the specific concavity of the septal deformity, the surgeon may affect the external contour and significantly improve the brow tip aesthetic lines as well as the overall symmetry. Bilateral asymmetric grafts also may be placed when needed.

Extended spreader grafts can be used to lengthen the nose. These grafts, with standard width and longer lengths, extend beyond the middle vault area into the tip and columellar subunits. In some cases, particularly in patients with relatively poor tip support, the extended spreader graft can be paired with a columellar strut graft in a “tongue-in-groove” technique [Guyuron, 2003].

When the rhinoplasty surgeon is addressing an overly narrow middle third of the nose, whether a congenital variant or more commonly the consequences of previous surgery or trauma, cartilage graft augmentation is required to improve the nasal airway and restore aesthetic balance. The primary goal of spreader graft placement is to add cartilage as a physical spacer, lateralizing the ULC away from the septum, in order to improve the nasal airway by increasing the INV area [Sheen, 1984; Becker Revision Rhinoplasty]. Secondary goals may include correction or prevention of an overly narrow middle vault and, when indicated aesthetically, widening the appearance of the middle third or increasing the length of the nose.

When undertaking an endonasal approach to spreader grafts, graft placement in precise pockets may be used. Spreader grafts may be suture-secured via an endonasal approach. However, in more complex nasal airway reconstruction – particularly those complicated by multiple bony and cartilaginous abnormalities – an external (open) rhinoplasty approach facilitates accurate dissection and suture fixation of the grafts [Toriumi, 1993].

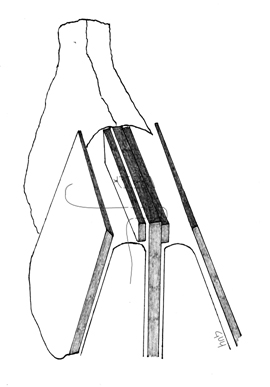

In determining the length of cartilage needed, the graft must be able to span the distance in the precise pocket, from just under the nasal bones to the anterior septal angle. This length is variable, but typically falls in the range of 2 to 3cm. One variation is an extended spreader grafdt, in which the grafts are extended beyond the anterior septal angle, with the intention of lengthening a nose. The appropriate width or thickness of the spreader graft also can be defined. This is generally 1 to 3mm in thickness, in order to achieve the desired functional effect without causing excessive middle vault widening. Ultimately, experience is required to develop reliable surgical judgment regarding the appropriate width and length of the spreader grafts.

In a primary rhinoplasty the most commonly used and easily accessible donor site is the quadrangular cartilage of the nasal septum. This provides a large supply of cartilage and is accessible at the same time as the approach for the rhinoplasty. During a primary rhinoplasty, there is generally adequate septal cartilage available to carve multiple spreader grafts provided that the surgeon is able to remove it as a single piece. In the case of a significant septal deformity or fracture, however, this may not be useable. During the septal cartilage harvest, the surgeon must keep in mind that a 1.5cm L-strut of cartilage should be left both caudally and dorsally, in order to support the middle vault and prevent dorsal collapse.

In revision rhinoplasty, a detailed preoperative evaluation (including inspection and palpation of the nasal septum) is critical in surgical planning to determine if sufficient septal cartilage is available to harvest for spreader grafting. Prior operative records may also be helpful when they are available. If the quadrangular cartilage has already been used, the surgeon should look to the conchal cartilage as the next donor site. While harvest of auricular cartilage from the concha cavum or cymba is also relatively straightforward, the patient must be aware of the risks of the second surgical site. In a multiple revision rhinoplasty case, the surgeon may consider costal cartilage – particularly if a large source of cartilage is needed for carving of multiple grafts. The patient and surgeon must weigh the benefits of the various donor site options against the associated risks.

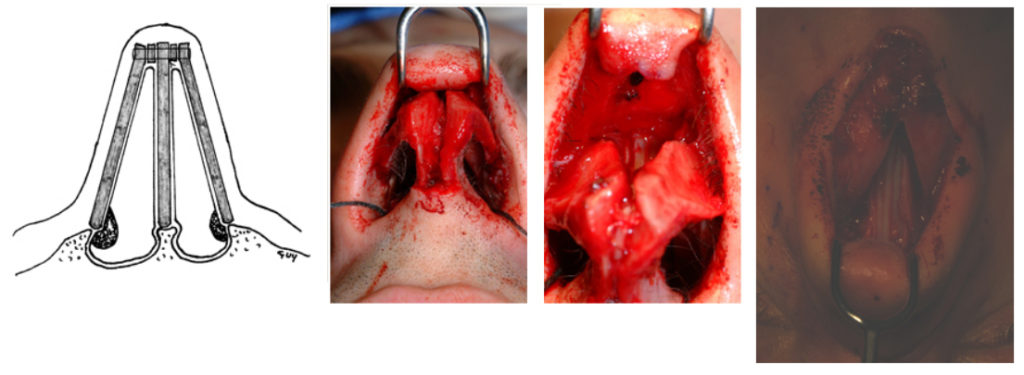

For this article, the open rhinoplasty approach to spreader grafts is described. (FIGURES) The nose is first opened in the standard fashion with marginal incisions bilaterally that are connected with a “W” or stair-stepped columellar incision. Once skin-soft tissue envelope has been dissected and the ULC and LLC have been appropriately exposed, the rhinoplasty surgeon may undertake dorsal hump reduction if indicated, as well as any planned osteotomies. The surgeon should separate the ULC from the dorsal septum in the submucoperichondrial plane. Of note, efforts are made to maintain an intact mucoperichondrium, which is of significant benefit in maintaining support for the ULC. When taking down the dorsal hump, mucosal protection can be achieved by conservative stepwise shaving of the ULC under direct visualization. Alternatively, the surgeon can elevate mucosal tunnels and separate the ULCs from the dorsal septum prior to hump reduction.

With the ULC separated from the dorsal septum, the spreader grafts may be placed as a “spacer” between these two structures. With the spreader grafts in place, they are then secured in a “sandwich-like” fashion with horizontal mattress sutures. Absorbable suture, such as a clear 5-0 polydioxanone (PDS), Maxon or Monocryl, is utilized to ensure that the ULC, spreader grafts, and dorsal septum are all included in each throw. It is important to use a needle of adequate size, such as a PS-2, so that all of the appropriate structures are engaged with single, smooth pass of the needle.

When using suture fixation to secure the spreader grafts via an external approach, it is important to gently stretch the ULC toward the anterior septal angle when reattaching them. This suture will thus place gentle traction on the ULC – mitigating against the risk of buckling as the tissues heal [Toriumi #1]. After the grafts have been stabilized, the nose is closed in the standard fashion.

While the placement of bilateral spreader grafts have been discussed here, asymmetry of the middle nasal vault may, at times, be more appropriately addressed with the placement of a unilateral spreader graft or stacked grafts of unequal thickness. [Toriumi, 1995] This technique is helpful in camouflaging mild asymmetries of the middle nasal vault.

However, it may be preferable in cases of a deviated middle vault to apply bilateral spreader grafts as part of the treatment plan. These bilateral grafts are placed with the intention of splinting such a dorsal septal deviations (particularly if the dorsal septum has been scored).

Complications

Complications related to spreader graft placement include aesthetic and functional complications. Aesthetic complications may occur if the spreader graft creates an overwidened nose, or if inadequate spreader graft width results in a persistently narrow nose. Also, graft shifting may result in a palpable or visible irregularity. Functional complications include synechiae, which are relatively infrequent in spreader graft placement and are generally related to unintended abrasions or lacerations of the nasal lining. While uncommon in spreader graft placement, synechiae complicate approximately 7% of septal surgery, generally forming between the turbinates and the septum in the late wound-healing phases of recovery [Muhammad, 1997]. In endonasal rhinoplasty, great care should be taken to minimize the occurrence of adhesions at intranasal intercartilaginous incision sites or stab incisions created for precise pockets, as INV synechiae may result in failure of the spreader graft technique. This is less common in open approaches, as significantly less manipulation of the nasal lining occurs.

Outcome Assessment

Assessment of outcomes in rhinoplasty is difficult and highly subjective, and remains an inexact science. Straight-forward clinical assessment of postoperative nasal air flow can be performed in the clinic using the same techniques employed in the initial diagnostic visit. Clinical assessment, paired with a basic subjective response from the patient, has been the most frequently reported outcome assessment in the literature [Spielman]. More recently, though, there has been an interest in quantification of patient-reported outcomes. This has been prominently employed by Stewart, et al. in the study of septoplasty and inferior turbinate surgery using the nasal obstruction symptom evaluation (NOSE) scale [Stewart, 2004 (2)]. Rigorous assessments of spreader grafts, however, are more difficult to find and are generally surgeon-reported. While much of this has been positive, in the sense that surgeons have data to support the efficacy of their patient selection and treatments, lasting effects of nasal airway surgery have been difficult to document and preoperative prediction of patient benefit not been reliably achieved [Dinis, Siegel, Spielman, Konstantinidis].

Objective studies of improvement in nasal function after surgery for nasal obstruction have included assessment of nasal volumes, cross-sectional areas, and air flow patterns [Schlosser, Huang, Kemker, Reber, Dinis]. Schlosser and Park showed a 5.4% increase in minimal cross-sectional area at the INV in a cadaver model, which was further increased by the addition of flaring sutures [Schlosser]. In addition, the authors reported on a series of 34 patients who underwent spreader graft placement via an open technique, showing a significant improvement in patient-rated mean nasal patency. In a similar cadaver study of endoscope-assisted endonasal spreader graft placement, significant improvement in the INV area was also noted [Huang].

Acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry have also been used in postoperative assessments, in addition to diagnosis or selection of surgical candidates. The data regarding these measures is almost entirely derived from the septoplasty literature, however, and is decidedly mixed across studies. Dinis and Haider, for example, used rhinomanometry to assess septoplasty patients before and after surgery and then compared objective measures to patients’ reported satisfaction [Dinis]. They found that the measurements did not correlate well in many cases [Dinis]. Further, even in cases where rhinomanometry was useful in diagnosis, it failed to predict long term outcome (i.e., patient satisfaction years after surgery) [Dinis]. This result is supported by Kim, et al. who showed that acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry measures are not significantly correlated with patients’ subjective assessments of airway obstruction [Kim]. Since this is the ultimate driver of success in functional rhinoplasty and nasal airway surgery, the authors emphasize that objective assessments should not be overvalued relative to the patients’ subjective impressions. This further underscores utility of standardized, validated clinical outcomes instruments for research purposes.

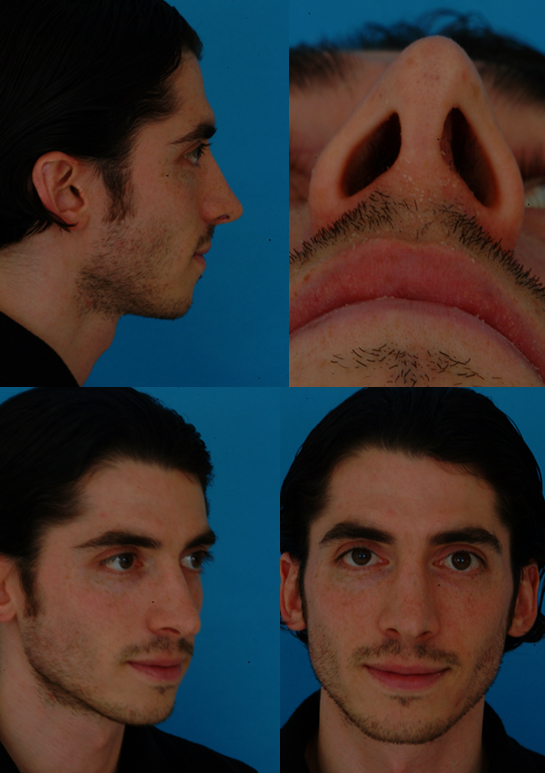

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

Case 2

References

- Tardy ME. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose, New York, NY Raven 1990, 55-97.

- Becker DG. Revision Rhinoplasty.

- Cole P. The Four Components of the Nasal Valve. Am J Rhinol, 2003;17(2):107-110.

- McCaffrey TV. Rhinomanometry and Diagnosis of Nasal Obstruction. Facial Plastic Surgery, 1990;7(4): 266-273.

- Joe SA. The assessment and treatment of nasal obstruction after rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am, 2004;12:451-458.

- Beekhuis GJ. Nasal obstruction after rhinoplasty: etiology and techniques for correction. Laryngoscope, 1976;86(4): 540-548.

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault in rhinoplasty. Operative Tech Plast Recon Surg, 1995;2:16-30.

- Constantinides MS, Adamson PA, Cole P. The long-term effects of open cosmetic rhinoplasty on nasal air flow. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1996;122(1):41-45.

- Spielmann PM, White PS, Hussain SSM. Surgical Techniques for Treatment of Nasal Valve Collapse: A Systematic Review. Laryngoscope, 2009;119:1281-1290.

- Chandra RK, Patadia MO, Raviv J. Diagnosis of nasal airway obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am, 2009;42:207-225.

- Lee J, White WM, Constantinides M. Surgical and nonsurgical treatments of the nasal valves. Otolaryngol Clin N Am, 2009;42:495-511.

- Becker DG, Bloom JD, Gudis D. A patient seeking aesthetic revision rhinoplasty and correction of nasal obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin N Am, 2009;42:557-565.

- Constantinides M, Galli SKD, Miller PJ. A simple and reliable method of patient evaluation in the surgical treatment of nasal obstruction. ENT Journal, 2002;81(10):734-737.

- Lanfanchi PV, Steiger J, Sparano A, et al. Diagnostic and surgical endoscopy in functional rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg, 2004;20:207-15.

- Corey JP. A comparison of the nasal cross-sectional areas and volumes obtained with acoustic rhinometry and magnetic resonance imaging. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1997;117:349.

- Lal D, Corey JP. Acoustic rhinometry and its uses in rhinology and diagnosis of nasal obstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am, 2004;12(4):397-405.

- Cakmak O, Coskun M, Celik H, et al. Value of acoustic rhinometry for measuring nasal valve area. Laryngoscope, 2003;113:295-302.

- Boccieri A, Macro C, Pascali M. The Use of Spreader Grafts in Primary Rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg 2005;55(2):127-131.

- Palacin JM, Bravo FG, Zeky R, Schwarze H. Controlling Nasal Length with Extended Spreader Grafts: A Reliable Technique in Primary Rhinoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg, 2007; 31:645-650.

- Guyuron B, Varghai A. Lengthening the Nose with Tongue-in-Groove Technique. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2003;111:1533-1539.

- Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg, 1984;73:230-237.

- Ballert JA, Park SS. Functional considerations in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg, 2008;24:348-357.

- Guyuron B. Nasal osteotomy and airway changes. Plast Reconstr Surg, 1998;102(3):856-860.

- Toriumi DM. Ries WR. Innovative surgical management of the crooked nose. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am, 1993;1:63-78.

- Muhammad IA, Rahman Nabil-ur. Complications of septoplasty surgery. Facial Plast Surg, 1997;13(1):3-14.

- Schwab JA, Pirsig W. Complications of septal surgery. Facial Plast Surg, 1997;13(1):3-14.

- Rettinger G, Kirsche H. Complications in septoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1995;121(6):681-684.

- Malki D, Quine SM, Pfleiderer AG. Nasal splints, revisited. J Laryngol Otol, 1999;113(8):725-727.

- Guyuron B, Vaughan C. Evaluation of stents following septoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 1995;19(1):75-77.

- Cook JA, Murrant NJ, Evans KL, et al. Intranasal splints and their effects on intranasal adhesions and septal stability. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, 1992;17(1):24-27.

- Bateman ND, Woolford TJ. Informed consent for septal surgery: the evidence-base. J Laryngol Otol, 2003;117(3):186-189.

- Vuyk HD, Langenhuijsen KJ. Aesthetic sequelae of septoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, 1997;22(3):226-232.

- Byrd SH, Salomon J, Flood J. Correction of the crooked nose. Plast Reconstr Surg, 1998;102(6):2148-2157.

- Daudia A, Alkhaddour U, Sithole J, et al. A prospective objective study of the cosmetic sequelae of nasal septal surgery. Acta Otolaryngol, 2006;126(11):1201-1205.

- Honrado CP, Pastorek NJ. Preventing complications in facial plastic surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2006;14(4):265-269.

- Spielmann PM, White PS, Hussain SSM. Surgical Techniques for Treatment of Nasal Valve Collapse: A Systematic Review. Laryngoscope, 2009;119:1281-1290.

- Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, et al. Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) Scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2004;130:157-163.

- Stewart MG, Smith TL, Weaver EM, et al. Outcomes after nasal septoplasty: Results from the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness (NOSE) Study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2004;130:283-290.

- Dinis PB, Haider H. Septoplasty: Long-Term Evaluation of Results. Am J Otolaryngol, 2002;23(2):85-90.

- Siegel NS, Gliklich RE, Taghizadeh F, Chang Y. Outcomes of septoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2000;122:228-232.

- Konstantinidis I, Triaridis S, Triaridis A, et al. Long term results following nasal septal surgery: Focus on patients’ satisfaction. Auris Nasis Larynx, 2005;32(4):369-374.

- Schlosser RJ, Park SS. Surgery for the Dysfunctional Nasal Valve: Cadaveric Analysis and Clinical Outcomes. Arch Facial Plast Surg, 1999;1:105-110.

- Huang C, Manarey CRA, Anand VK. Endoscopic placement of spreader grafts in the nasal valve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2006;134: 1001-1005.

- Kemker B, Liu X, Gungor A, et al. Effect of nasal surgery on the nasal cavity as determined by acoustic rhinometry. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1999;121(5):567-571.

- Reber M, Rahm F, Monnier P. The role of acoustic rhinometry in the pre- and postoperative evaluation of surgery for nasal obstruction. Rhinology, 1998;36(4):184-187.

- Kim CS, Moon BK, Jung DH, Min YG. Correlation between nasal obstruction symptoms and objective parameters of acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry. Auris Nasus Larynx, 1998;25(1):45-48.

9. Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Open Structure Rhinoplasty – Featured Technical Points and Long-Term Follow-Up. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1):

1-22, August 1993.

10. Toriumi DM. Management of the Middle Nasal Vault. Operative Techniques in Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2(1):16-30, February 1995.

11. Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative Surgical Management of the Crooked Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1): 63-78, August 1993.

12. Toriumi DM, Johnson CM. Management of the Lower Third of the Nose – Open Structure Rhinoplasty Technique. Chapter 33 in Facial Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery

(ed Papel and Nachlas), pp 305-313.

13.Gunter JP. The merits of the open approach in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 99(3): 863-867, 1997.

14. Thomas JR. External rhinoplasty:intact columellar approach. Laryngoscope 100(2 Pt 1):206-208, 1990.

15 Larrabee WF. Open Rhinoplasty and the Upper Third of the Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1):1993, 23-38.

16 Becker DG. The Powered Rasp, Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 2001.

17. Constantian MB, Clardy RB. The Relative Importance of Septal and Nasal Valvular Surgery in Correcting Airway Obstruction in Primary and Secondary Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

18. Teichgraeber JF, Wainwright DJ. The Treatment of Nasal Valve Obstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery93(6):1174- 1184, 1994.

19. Sheen JH. Spreader Graft: A Method of Reconstructing the Roof of the Middle Nasal Vault Following Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 73(2):1984, 230-237.

20. Aiach G. Atlas de Rhinoplastie, Paris, France, Masson, 1989, pp 74-85.

21. Soliemanzadeh P, Kridel RWH. Nasal tip overprojection: algorithm of surgical deprojection techniquesand introductionto medial crural overlay. Arch Facial Plastic Surg 2005;7:374-380.

22. Konior RJ, Kridel RWH. Controlled nasal tip postioning via the Open Rhinoplasty Approach. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993: 53-62.

23. Adamson PA. Nasal Tip Surgery in Open Rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 1(1):1193, 39-52.

24. Wise, JB, Becker SS, Sparano A, Steiger J, Becker DG. Intermediate Crural Overlay in Rhinoplasty: A Deprojection Technique that Shortens the Medial Leg of the Tripod without Lengthening the Nose. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. Vol 8:240-244, 2006.

25. Perkins SW, Tardy ME. External Columellar Incisional Approach to Revision of the Lower Third of the Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, pp 79-98.

26. Pastorek NJ, Becker DG. Treating the Caudal Septal Deflection. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery, 2: 217-220, 2000.

27. Toriumi DM, Ries WR. Innovative Surgical Management of the Crooked Nose. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, 63-78.

28. Adamson PA. Nasal Tip Surgery in Open Rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America Vol 1(1) 1993, 39-52.

29. Perkins SW. The evolution of the combined use of endonasal and external columellar approaches to rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 12(2004):35-