INTRODUCTION

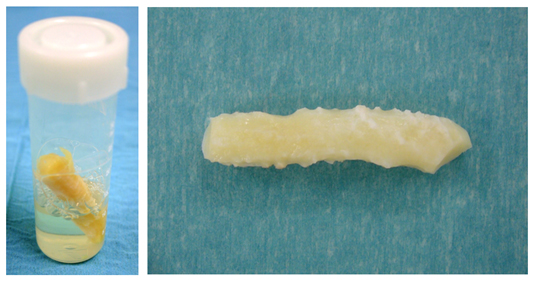

Irradiated homologous rib grafts (IHRGs), might be an alternative for autologous cartilage grafts in case there is insufficient quantity-, or quality or when the shape of the autologous grafts is not adequate for a successful nasal reconstruction. IHRGs can be used to augment and/or to provide structural support in a recipient site. Alloplasts, like silicone, are less favorable compared with IHRGs due to the higher infection-, extrusion- and foreign body response rates. The accepted advantages of IHRGs are the elimination of additional incisions for graft harvesting and donor site morbidity, as well as ready availability. The first publication relating to the use of IHRGs in the human face dates back almost half a century [1]. Since that study, multiple clinical reports have been published, often with low complication and resorption rates [2-5]. The incidence of resorption however, increases with the duration of follow-up [6-9]. In addition to the time factor, the recipient site also seems to affect the rate of resorption [2,10,11]. This could be explained by two factors. Firstly, the vascularity of the implant in the recipient bed. Relatively low vascularity is thought to be associated with higher resorption rates [8,11]. Secondly, trauma/micro-trauma due to muscle activity and stresses may be associated with higher resorption rates [9, 10]. IHRGs used to reconstruct the auricle, for example, were more susceptible to graft failure than nasal grafts [11]. Resorption of IHRGs is often characterised by a loss of support function without loss of volume. The latter can be explained by the replacement of the original IHRGs by fibrous scar tissue [2,8,10]. For most nasal grafts, this type of resorption has no negative influence on the long term functional- or aesthetic result [9]. Recent long-term follow-up studies [9,12] have identified the nasal regions where IHRGs are safe to use and determined that they provide a stable long-term result in terms of the structural support function and volume preservation. Only shield grafts showed some loss of nasal tip definition and refinement. For this type of nasal graft we advise the use of autologous cartilage. In general there are two types of IHRGs, a commercially available product named Tutoplast (Fig.1) (Tutogen Medical, GmbH, Neunkirchen am Brand, Germany) and IHRGs from a donor bank. The first is chemically treated (3% hydrogen peroxide followed by pure acetone), than the rib undergoes evaporation under vacuum before irradiation with a minimum dose of 17.8 kGy. The second type, IHRGs from a donor bank, is only irradiated with a minimum dose of 30 kGy. Both types are stored in saline solution.

Figure 1 (A) Irradiated costal cartilage is stored at room temperature in a container with 0.9% NaCl. (B) Before use, the rib should be washed three times in 500 ml saline.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF IRRADIATED RIB GRAFTS

General instructions

During surgery the grafts should be removed aseptically from the container and rinsed three times in 500 mL of sterile saline solution. To prevent warping, the outer layers should be removed, including the perichondrium, leaving only the central portion of the donor cartilage for reconstruction material. Graft implants should be shaped, sculptured and bevelled with fresh scalpels. An open approach rhinoplasty is preferable above an endonasal approach to prevent postoperative infection by minimising intranasal incisions and taking advantage of the elongated distance between the graft implants and the outer world. In order to prevent mobility of the implants the grafts should be placed in a precisely created pocket. To further reduce the risk of graft mobilisation, the grafts can be sutured in place using 6/0 nylon or semi-absorbable sutures. At the end of surgery the incisions should be closed securely in one or two layers. A light packing of the nose with a 2 cm gauze covered with topical antibiotic cream (for example: Terracortril) is carried out in both nasal cavities for 24 to 48 hours. The nose is dressed in order to ensure good tissue approximation and to prevent dead space between the soft tissue envelope and the nasal skeleton. This is carried out using steristrips and a nasal splint. Underneath the steristrips a small piece of compressed Gelfoam is placed on the nasal dorsum to prevent detachment of the skin in this area when the tape is removed. The sutures and dressing can be removed after 7 days. To prevent postoperative infection, oral systemic broad spectrum antibiotics (for example: amoxicillin / clavulanic acid: 500/125 mg, every eight hours) can be administered during seven days.

Resorption of IHRGs

In general, the reported resorption rates of IHRGs is low [1-2,4-5,11-21]. A recent study, with a follow-up dating back 9 years (average 51 months), showed that the use of IHRGs from Tutoplast is save with relatively low complication rates [9]. The resorption rate increases with the duration of follow-up. This resorption was characterized by loss in structural support rather than loss of volume. This was probably due to the replacement of the original grafts by fibrous scar tissue [8]. Complete resorption with a need for revision surgery however is very uncommon. For most types of nasal grafts, moderate resorption does not negatively influence the functional or aesthetic result. Only for shield grafts moderate resorption showed some loss in nasal tip definition and nasal tip projection [9]. For shield grafts therefore we advice the use of autogenous grafts, especially auricular cartilage. In a study with leprosy patients [22], autogenous costal cartilage shield grafts underwent more resorption (55%) than auricular grafts (23%). Auricular cartilage is probably more resistant to resorption caused by micro-trauma and stresses from the overlying soft tissue envelope in the nasal tip area than IHRGs and autogenous costal cartilage.

Infection

A localised and temporarily erythema of the skin in the postoperative phase is a relatively frequent complication at the site of the columella. This symptom, however, completely disappears with the use of orally and/or locally (ointment) administered antibiotics. Frequent postoperative assessments after surgery with IHRGs are therefore essential to avoid progression of the inflammation response and/or infection. In general, the chance of infection after rhinoplasty with IHRGs is not higher compared with autogenous grafts [12]. Chronic infection and extrusion of IHRGs are extremely rare. Nasal trauma however, is associated with acute infections that, in general, is well treated with broad-spectrum orally antibiotics.

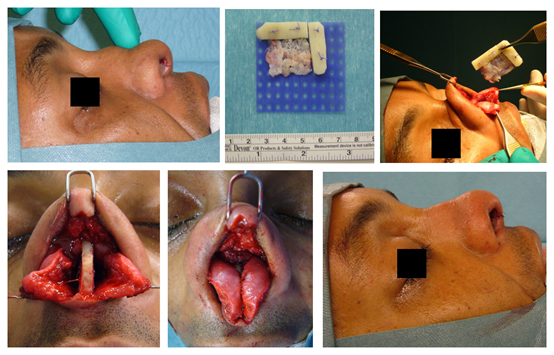

In patients with a chronic infection due to an alloplast implant, like silicone, immediate reconstruction with IHRGs can take place safely [9,23,24] (Fig. 2) . Immediate reconstruction has two advantages; patients need not wait for a secondary reconstruction which is emotionally beneficial. Secondly, there will be less change of retraction of the pocket underneath the soft tissue envelope as a result of scar tissue formation. [9,24]. In such cases of chronic infection due to alloplasts, impregnation of the IHRGs with antibiotics could conceivably result in a further reduction of the risk of postoperative infection [25].

Figure 2 (A) This patient developed a chronic infection 40 years after implantation of a silicone implant. (B) The soft tissue envelope of the nasal dorsum was at risk with signs of extrusion of the implant. (C) The silicone implant was removed through an external approach rhinoplasty. In the same setting the nasal skeleton was reconstructed using IHRGs, a dorsal onlay graft and a columellar strut. (D) Post-operative result one year after surgery.

Warping

A controlled experimental study showed that the rate of warping in irradiated and non-irradiated costal cartilage was proven to be similar for at least four weeks [26]. In order to prevent warping, the outer layers of perichondrium should be removed using only the central portion of the rib grafts. Leave the IHRGs in saline for 30-45 minutes before implantation and fixation in the nose, most frequently warping can already be detected and thus avoided. Internal stabilization with Kirschner wires is not advocated.

Mobility

Mobility of the implants, especially dorsal onlay grafts should be prevented using precisely created pockets and fixation of the grafts with permanent or semi-permanent sutures, usually 6/0 sutures are sufficient.

IRRADIATED RIB GRAFTS: APPLICATIONS

The main recipient sites for IHRGs in rhinoplasty are:

- dorsum

- septum

- nasal side wall

- radix

- naso-labial groove

- ala

- columella

Reconstruction of the nasal septum is essential in patients with loss of septal cartilage. This loss can be the result of over-resection or due to destruction after a nasal septal hematoma or -abscess due to trauma or previous surgery. Without treatment these patients will develop a saddle nose deformity. In such cases IHRGs can be used to reconstruct the nasal septum. A dorsal- and a caudal septal replacement splint avoid sagging of the dorsum and retraction of the columella, respectively (Fig. 3). An alternative is the use of a dorsal onlay graft which only camouflages the saddle deformity.

Figure 3 (A) Lateral view of a patient with a saddle nose deformity. There was almost complete loss of septal cartilage due to a nasal septal abscess after septal surgery performed elsewhere. (B) IHRGs were used to attach a dorsal splint (horizontal portion) to a caudal splint (vertical portion), the grafts were fixed to PDS plate (blue), leftover septal cartilage was crushed and placed behind the caudal splint. (C) The implant was inserted between the intact mucoperichondrium layers. (D) The dorsal splint was fixed to the bony pyramid using a permanent 4/0 nylon suture. (E) After mattress sutures through and through the nasal septum the broken columellar incision was closed (F).

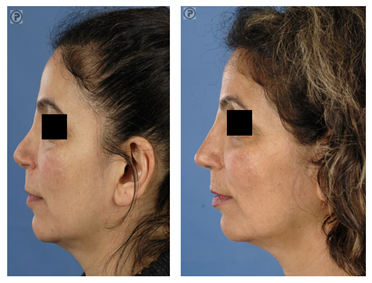

Revision surgery is often associated with over-resection of cartilaginous and/or bony structures of the nose. Many of these patients suffer from functional- and aesthetic problems. Rib grafts are often required in order to achieve a stable long-term postoperative result in line with the expectations of the patient. Particularly in cases of over-resection of the nasal dorsum, rib grafts are in favour of auricular cartilage to achieve a smooth and refined result (Fig. 4, 5).

Figure 4 (A) Revision surgery, this patient had multiple rhinoplasties performed elsewhere. There was over-resection of the bony pyramid, the UL and LL cartilages and of the nasal septum. (B, C) All nasal grafts were removed, leaving only the soft tissue envelope. (D) The nasal dorsum and caudal septum were reconstructed using a dorsal onlay graft (left side) attached to a strong columellar strut (right side). The nasal tip was reconstructed with auricular cartilage (shield graft and lateral crus replacement grafts). (E) Post-operative result one year after surgery. (F) Lateral pre-operative view, note the columellar retraction and absence of the nasal tip. (G) Post-operative lateral view.

Figure 5 (A) Revision surgery. Pre-operative frontal view of a patient with over-resection of the upper- and middle third of the nasal dorsum and of the lower lateral (LL) cartilages. (B) Reconstruction was performed using IHRGs. A dorsal onlay graft and side-wall grafts were used to augment the dorsum and to create the illusion of smoother lines from the eyebrows to the nasal tip defining points. (C) Pre-operative lateral view. Note that the dorsum was over-resected in combination with underprojection and overrotation of the nasal tip. (D) Post-operative lateral view, the nose was lengthened using a IHR caudal septal replacement graft, the LL were reconstructed with lateral crus replacement grafts.

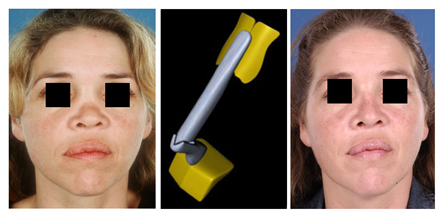

IHRGs can also be used to replace the bony pyramid and middle third of the nasal dorsum (Fig. 6). A dorsal onlay graft attached to a columellar strut can give the impression of a natural nasal skeleton underneath the soft tissue envelope.

Figure 6 (A) Pre-operative frontal view of a patient who had nasal trauma in childhood. There was complete lack of her bony pyramid and underdevelopment of the cartilaginous dorsum. (B) Reconstruction was performed using IHRGs. A dorsal onlay graft was attached to a columellar strut in such fashion that the height could be adjusted before permanent fixation with non-absorbable sutures. (C) Post-operative frontal view. (D) Pre-operative lateral view. (E) Post-operative lateral view.

CONCLUSION

In rhinoplasty, the use of irradiated homologous rib grafts (IHRGs) has relatively low complication rates. The resorption rate increased with duration of follow-up. Resorption is characterised by a loss of structural support rather than loss of volume. This phenomenon is probably due to the replacement of the original grafts by fibrous scar tissue. Complete resorption requiring revision surgery is very uncommon. Moderate resorption is seen frequently in long-term follow up. For most types of nasal grafts, moderate resorption does not negatively influence the functional or aesthetic result. However, in cases of moderate resorption of IHRG shield grafts, loss of nasal tip definition and nasal tip projection can occur. In cases where a shield graft is a clinical necessity, we advise the use of autogenous auricular cartilage grafts.

REFERENCES

- Dingman R.O., Grabb W.C. Costal cartilage homografts preserved by irradiation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 28: 562-567, 1961.

- Kridel R.W.H., Konior R.J. Irradiated cartilage grafts in the nose, a preliminary report. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 119: 24-30, 1993.

- Chaffoo R.A.K., Goode R.L. Irradiated homologous cartilage in augmentation rginoplasty. In: Stucker, F.J., ed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Head and neck, Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium. Philadelphia, Pa; B.C. Decker; 297-300, 1989.

- Murakami C.S., Cook T.A., Guida R.A. Nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 117: 327-330, 1991.

- Schuller D.E., Bardach J., Krause C.J., Irradiated homologous costal cartilage for facial contour restoration. Arch. Otolaryngol. 103: 12-15, 1977.

- Maves M.D. Facial plastic analysis and discussion: nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 117: 331, 1991.

- Babin R.W., Ryu J.H., Gantz B.J., Maynard J.A. Survival of implanted irradiated cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 90: 75-80, 1982.

- Welling D.B., Maves M.D., Schuller D.E., Bardach J. Irradiated homologous cartilage grafts: long-term results. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 114: 291-295, 1988.

- Menger D.J., Nolst Trenité G.J. Irradiated homologous rib grafts in nasal reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 12(2): 114-118, 2010.

- Donald P.J. Cartilage grafting in facial reconstruction with special consideration of irradiated grafts. Laryngoscope. 96: 786-807, 1986.

- Burke A.J.C., Wang T.D., Cook T.A. Irradiated homograft rib cartilage in facial reconstruction. Arch Facial plast Surg. 6: 334-341, 2004.

- Kridel R.W.H., Ashoori F., Liu E.S., Hart C.G. Long-term use and follow-up of irradiated homologous costal cartilage grafts in the nose. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 11(6): 378-394, 2009.

- Donald P.J., Cole A. Cartilage implantation in Head and Neck surgery: report of a national survey. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 90: 85-89, 1982.

- Dingman R.O. Follow-up clinic on costal cartilage homografts preserved by irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 50: 516-517, 1972.

- Demirkan F., Arslan E., Unal S., Aksoy A. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage: versatile grafting material for rhinoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 27:213-220, 2003.

- Strauch B., Wallach S.W. Reconstruction with irradiated homograft costal cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 111(7): 2405-2413, 2003.

- Linberg J.V., Anderson, R.L., Edwards, J.J., et al. Preserved irradiated homologous cartilage for orbital reconstruction. Ophtalmic Surg. 11: 457-462, 1980.

- Lefkovits G. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage for augmentation rhinoplasty. Annals of Plast Surg. 4: 317-327, 1990.

- Strauch B., Erhard H.A., Baum T. Use of irradiated cartilage in rhinoplsty of the non-Caucasian nose. Aesthet Surg J. 24(4): 324-330, 2004.

- Velidedeoglu H., Demir Z., Sahin U., Kurtay A., Erol O.O. Block and surgicel – wrapped diced solvent – preserved costal cartilage homograft application for nasal augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 115: 2081-2093, 2005.

- Song H.M., Lee B.J., Jang Y.J. Processed costal cartilage homograft in rhinoplasty: the asian Medical Center experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 134(4): 485-489, 2008.

- Menger D.J., Fokkens W.J., Lohuis P.J., Ingels K.J., Nolst Trenité G.J. Reconstructive surgery of the leprosy nose: a new approach. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 60(2):152-62, 2007.

- Raghavan U., Jones N.S., Romo T. 3rd. Immediate autogenous cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty after alloplastic implant rejection. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 6(3): 192-196, 2004.

- Clark J.M., Cook T.A. Immediate reconstruction of extruded alloplastic nasal implants with irradiated homograft costal cartilage. The laryngoscope 112: 968-974, 2002.

- Tasman A.J., Wallner F., Neumeier R. Antibiotic impregnation of cartilage implants: diffusion kinetics of fluoroquinolones. Laryngorhinootologie, 79(1): 30-33, 2000.

- Adams Jr. W.P., Rohrich R.J., Gunter J.P., Clark C.P., Robinson J.B. The rate of warping in irradiated and nonirradiated homograft rib cartilage: a controlled comparison and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 103(1): 265-270, 1999.