Introduction

Autologous costal cartilage is an excellent source of grafting material in the nose. It has several advantages when compared to other autologous grafts. First of all, it is versatile and can be carved into many different shapes and sizes depending on the patient’s deformity. It is also more abundant and usually stronger than other cartilages. There are several situations where abundant, strong cartilage is necessary, precluding the use of other grafting materials. Examples of such situations include nasal reconstruction following tumor resection, saddle nose deformity, ethnic rhinoplasty, congenital deformity, and revision (secondary) rhinoplasty. Finally, it is relatively easy to harvest using a small incision. In the senior author’s experience, rib cartilage can be harvested in less than 30 minutes.

Alternative grafts

Autologous grafts

Septal and auricular cartilages are potential alternative graft sites. Septal cartilage can be easily harvested during septoplasty, thereby requiring no additional prepping or incisions. It is generally stronger than auricular cartilage making it a good choice for minor tip work and dorsal augmentation. The disadvantage is that most people do not have enough septal cartilage for the work that is necessary. This is particularly true in congenital rhinoplasty patients where the septum tends to be foreshortened.

Ear cartilage is more abundant than septal cartilage. It is relatively easy to harvest through a post auricular incision or through a conchal incision when a composite chrondrocutaneous graft is necessary. The donor site is well-hidden and post-operative ear deformity is uncommon. Ear cartilage is commonly used for tip, alar batten, alar strut, spreader, and columellar strut grafts. However, this cartilage is relatively weak and irregular in shape, which may make it unsuitable when a strong dorsal strut is necessary such as with a saddle nose deformity or following neoplastic resection.

Alloplastic grafts

There are a number of alloplastic implants available including polytetrafluoroethylene, porous polyethylene and silicone1-4. The main advantage of such implants is that they are readily available and therefore save time and avoid donor site morbidity. Unfortunately, these materials have a higher rate of infection and extrusion than autologous materials. In addition, they can lead to a foreign body reaction with resultant damage to the overlying skin. The use of alloplastic grafts has become less popular for these reasons.

Homografts

Acellular dermis and irradiated cartilage are 2 homografts that have gained popularity over the past several years5-6. They offer the same advantages as alloplastic grafts but are less prone to foreign body reaction. In addition, they are less likely to warp than costal cartilage. However, the use of homografts carries with it the possibility of disease transmission and unpredictable resorption rates. They also have limited availability due to lack of donors and cost.

How to harvest and carve costal cartilage

Preparation: Costal cartilage is typically harvested from the right chest unless the patient has had previous surgery in this area. A 3-5cm straight incision is planned overlying the cartilage of the 6th rib, which allows access to the synchondrosis of ribs 6-9 .The size of the incision is dependent on the size of the patient and the amount of cartilage required. In women, this incision is placed just below the inframamillary crease being careful not to extend the incision onto the breast. The planned incision site is then injected with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epineprine. The entire right chest from the clavicle to the umbilicus is prepped in the usual sterile fashion.

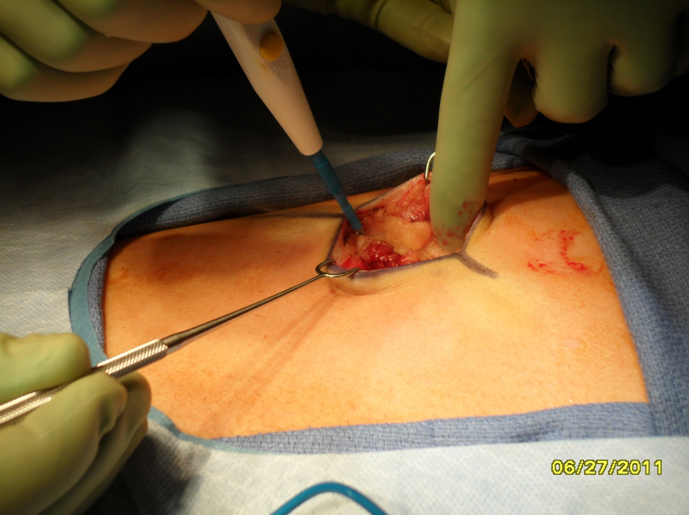

Incision: The skin incision is made using a 15 blade scalpel. Electrocautery is used to divide the underlying subcutaneous tissue. The rectus abdominis is identified running vertically through the surgical field. This is divided horizontally and retracted superiorly and inferiorly. The underlying rib is identified and bluntly dissected free from the surrounding tissue. The costochondral junction is identified laterally and medially to allow full access to the cartilage.

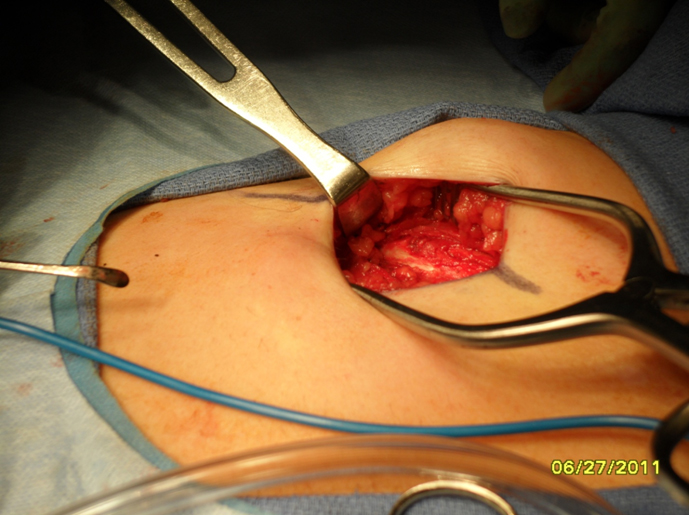

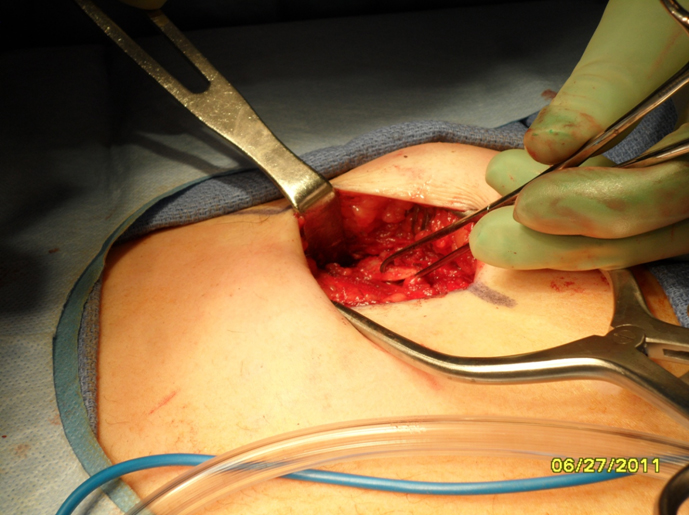

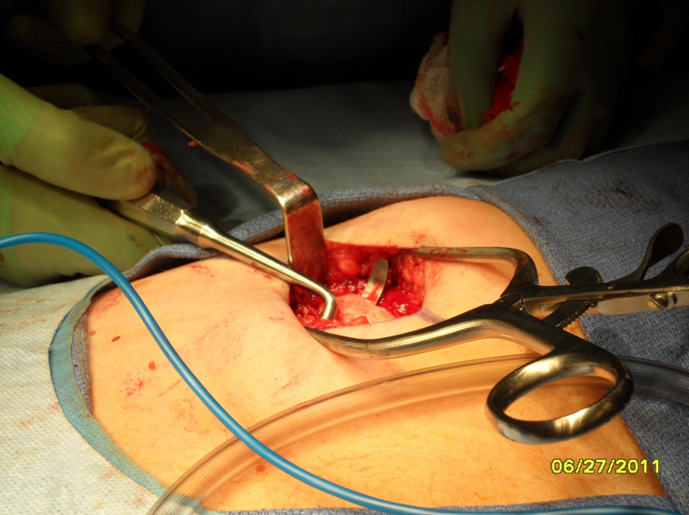

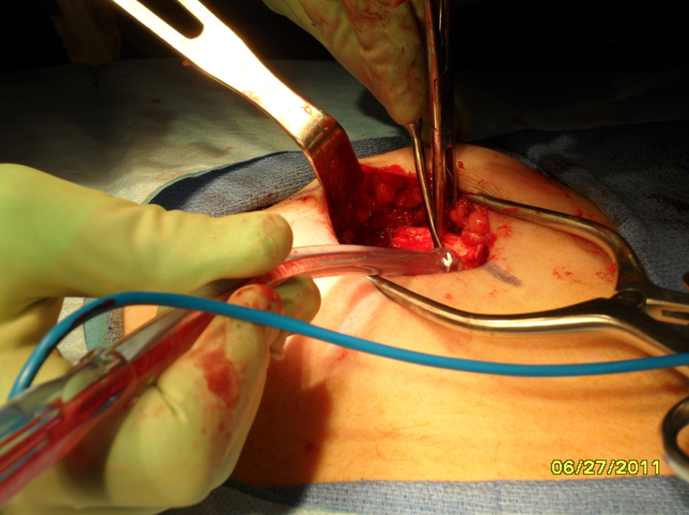

Harvest: The perichondrium is incised horizontally over the rib segment to be harvested. Vertical incisions are made through the perichondrium laterally and medially at the costochondral junctions to aid with subperichondrial dissection. Alternatively, perichondrium can be harvested at this time if necessary. Perichondrium can be used to camouflage grafts and hide small irregularities. A rib stripper is then used to develop the plane between the posterior perichondrium and the rib. At this time it is important to apply gentle upward traction on the rib graft to keep dissection within the subperichondrial plane and to avoid violating the parietal pleura. Fracturing of the rib cartilage should also be avoided while applying traction.Once the perichondrium is released posteriorly, a medial incision is made between the cartilage and (depending on the rib being harvested) the body of the sternum or synchondrosis. The incision is carried down through the cartilage being careful to leave the posterior perichondrium intact. The lateral incision is then made in a similar fashion. The rib graft is carefully removed from the wound and placed in gentamicin (50mg/500mL saline) solution until ready to carve.

1. Donor site inspection: The wound is evaluated for any obvious air leak. If none is seen, the wound is irrigated with sterile saline and a valsalva maneuver is performed. If no air leak is visualized, then the wound can be closed in layers with a closed suction drain left in place.

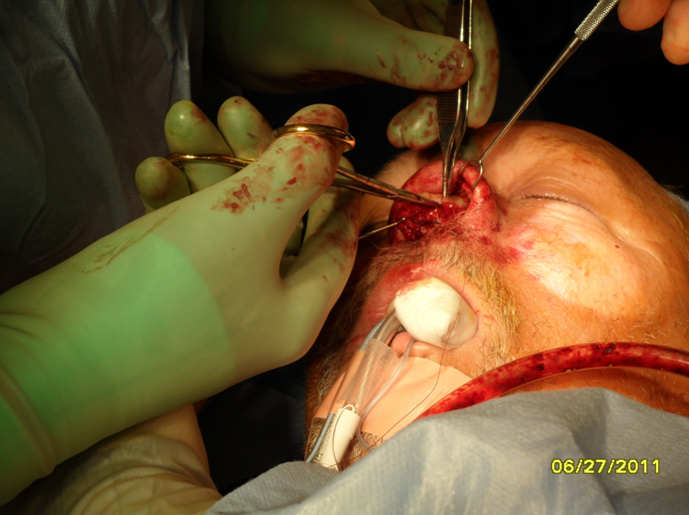

2. Carving: A 10 blade scalpel is used to carve the cartilage into a shape appropriate for the patient defect. In general, the dorsum of the nose has a gentle canoe shape.

Complications

Seroma or hematoma are the most common complications following rib cartilage harvest. These complications are avoided by using electrocautery during dissection, a closed suction drain for 5 days, and application of a pressure dressing at the conclusion of the procedure. If a seroma or hematoma still develops, it is needle aspirated under local anesthesia and a pressure dressing is reapplied.

Pneumothorax occurs when there is an injury to the parietal pleura. In contrast to traumatic pneumothorax, the visceral pleura is typically spared, eliminating the need for a formal tube thoracostomy. Instead, a red rubber catheter is placed into the chest cavity through the wound and suction applied to remove any free air. The anesthesiologist then applies positive pressure or valsalvas the patient to fully expand the lung. The red rubber catheter is then clamped and left in place. A 2.0 absorbable purse string suture is placed around the edges of the defect. While positive pressure is being applied by the Anesthesiologist, the red rubber catheter is withdrawn and the stitch is immediately tied. A post-operative chest x-ray should be ordered to confirm there is no large pneumothorax. 100% oxygen delivered by face mask can aid with resorption of small amounts of residual air.

Infection can occur at the graft donor or recipient sites. Graft infection can lead to accelerated resorption of the cartilage graft and thereby alter the surgical outcome. The authors use pre-operative and post-operative antibiotics to attempt to reduce infection risk. A single dose of IV cefazolin (clindamycin if penicillin allergic) is administered within 1 hour of skin incision and ciprofloxacin is continued for 7 days post-op.

Costal cartilage warping is a potential long-term complication7-8. Warping refers to bending of the cartilage over time, which can lead to visible external deformity. It has been shown that the central core of rib is less prone to warping and pieces of rib with a larger cross sectional area tend to warp less. Carving the cartilage incrementally over a few hours can help predict the course of warping and allow the surgeon to anticipate it. If a straight piece of cartilage is necessary, the central core of the harvested rib is used since it is less prone to warp.

References

- Ahn J, Honrado C, and Horn C. Combined silicone and cartilage implants: Augmentation rhinoplasty in Asian patients. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 6: 120, 2004.

- Conrad K and Gillman G. A 6-year experience with the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene in rhinoplasty. Plast.Reconstr. Surg. 101: 1675, 1998.

- Deva AK, Merten S, and Chang L. Silicone in nasal augmentation rhinoplasty: A decade of clinical experience. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102: 1230, 1998.

- Fanous N, Samaha M, and Yoskovitch A. Dacron implants in rhinoplasty: A review of 136 cases of tip and dorsum implants. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 4: 149, 2002.

- Kridel RW, Konior RJ. Irradiated cartilage grafts in the nose. A preliminary report. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:24–30.

- Jackson I T and Yavuzer R. AlloDerm for dorsal nasal irregularities. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 108: 1827, 2001.Harris S, Pan Y, Peterson R, Stal S, Spira M. Cartilage warping: an experimental model. PlastReconstrSurg 1993; 92:912–915.

- Kim DW, Shah AR, Toriumi DM. Concentric and eccentriccarved costal cartilage: a comparison of warping. Arch Facial PlastSurg 2006;8:42–46.