ABSTRACT

Revision rhinoplasty is a challenge in reconstruction to the rhinoplasty surgeon, both in the techniques of repair and the choice of implant material for augmentation grafting. Often, patients seeking revision or reconstructive rhinoplasty have previously undergone septoplasty with sacrifice of major amounts of septal cartilage. These situations confront the surgeon with the need for a decision about the material that will be used for structural grafting. The senior author follows the time-tested approach of generations of surgeons who have used exclusively autogenous material for nasal reconstruction because of its superior long-term survival characteristics, its ready availability in the head and neck region, its resistance to infection and resorption, and its bendability and flexibility when implanted in the nose. With this in mind, the subject of this article is the use of auricular cartilage in revision rhinoplasty. Careful strategic planning must be undertaken to get the maximal and ideal benefit from the auricular cartilage. The revision rhinoplasty surgeon must understand the anatomy of the external ear and must be able to manage the precious cartilage supply to get the maximum use of it in reconstructive rhinoplasty.

INTRODUCTION

Revision rhinoplasty has stimulated a variety of reconstructive techniques by surgeons dedicated to restoration of both nasal form and nasal function. Often, patients seeking revision or reconstructive rhinoplasty have previously undergone septoplasty with sacrifice of major amounts of septal cartilage. These situations confront the surgeon with the need for a decision about the material that will be used for structural grafting.

Implant materials may be categorized as autogenous tissue (cartilage, bone, fascia, and dermis), homograft materials (preserved, irradiated cartilage or bone, preserved acellular dermis or Alloderm, and others), and alloplastic materials. The senior author follows the time tested approach of generations of surgeons who have used exclusively autogenous material for nasal reconstruction because of its superior long-term survival characteristics, its ready availability in the head and neck region, its resistance to infection and resorption, and its bendability and flexibility when implanted in the nose).

The medical literature contains multiple reports that favor alloplasts for grafting. Although many alloplastic materials have emerged in the last 100 years, each has enjoyed only momentary success and then faded away as long-term difficulties with infection, extrusion, patient unacceptance, and other preventable complications became evident with time.

Gore Tex is the most recent alloplast championed in the literature. Godin et al. reported on 162 patients who received Gore-Tex implants during primary rhinoplasty and 147 patients who received Gore Tex implants for revision rhinoplasty. With an average of years follow-up, 2 of the 162 primary rhinoplasty patients (1.2%) had infections requiring removal of the Gore-Tex implants, and 8 of the 147 revision patients (5.4%) had infections requiring removal of the Gore-Tex.

When undertaking revision or reconstructive rhinoplasty requiring aesthetic and structural grafting, we always look first to the septum for additional residual cartilage. At times ample septal cartilage can be found despite a history of a prior septoplasty. Also, all other cartilaginous and bone sources in the nose are sought after and used when possible (Figs. 1, 2).

Figure 1 (A) This patient had a rhinoplasty elsewhere and had a pollybeak deformity. She had overresection of the upper third of her nose and underresection of the middle vault. (B) Using conservation principles, the cartilaginous pollybeak was excised but not discarded. This precious tissue was placed into a precise pocket in the upper portion to balance the nose. Therefore, no other cartilage grafting was required

Figure 2 (A) This patient has a saddle nose deformity after nasal fracture. (B) Rather than restore his nose completely to its pre-traumatic size, some balancing of the nose was undertaken. The autogenous material obtained from reduction of the upper nasal third was used as an augmentation graft to restore height to the middle third of the nose.

AURICULAR CARTILAGE ANATOMY

The subject of this article is the use of auricular cartilage in revision rhinoplasty. Careful strategic planning must be undertaken to obtain the maximal and ideal benefit from the auricular cartilage. The revision rhinoplasty surgeon must understand the anatomy of the external ear and must be able to manage the precious cartilage supply to get the maximum use of it in reconstructive rhinoplasty

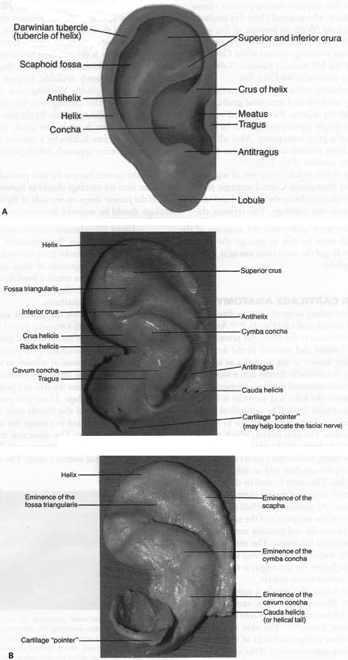

The revision rhinoplasty surgeon must be familiar with the anatomy of the external ear (Fig. 3). Among important surface features is the helix, the prominent rim of the auricle. Parallel and anterior to the helix is an-other prominence known as the antihelix or antihelical fold. Superiorly, the antihelix divides into a superior and inferior crus, which surround the fossa triangularis. The depression between the helix and antihelix is known as the scapha or scaphoid fossa. The antihelical fold surrounds the concha, a deep cavity posterior to the external auditory meatus. The crus helicis, which represents the beginning of the helix, divides the concha into a superior portion, the cymba conchae, and an inferior por tion, the cavum conchae. The cavity formed by the concha on the anterior (lateral) surface of the ear corresponds to a bulge or convexity on the posterior (medial) surface of the ear that is known as the eminentia of the concha.

Figure 3 TopograpHic landmarks of (A) external ear and lB) cartilaginous landmarks. (Reprinted with permssion from Surgical Anatomy of tHe Face, Larrabee and Makelski, Raven Press.

Anterior to the concha and partially covering the external auditory meatus is the tragus. The antitragus is posteroinferior to the tragus and is separated from it by the intertragic notch. Below the antitragus is the lobule that is composed of areolar tissue and fat.

Except for the lobule, the auricle is supported by thin, flexible elastic fibrocartilage. This cartilaginous framework is 0.5 to 1.0 mm thick and covered by a minimum of subcutaneous tissue. 1 – 12 The skin is loosely adherent to the posterior surface and helix of the auricular cartilage. The close approximation of the skin to the anterior surface of the cartilage provides the auricle with its unique topographic features.

AURICULAR CARTILAGE HARVEST

The majority of our grafts for revision rhinoplasty are harvested from the external ear. As long as the antihelical fold is not transgressed, no significant change results in the appearance of the ear, even by the removal of the entire concha cavum and concha cymba. Segments of 3.5 to 4 cm are commonly available. In most patients, the cartilage is stiff yet pliable. Warping rarely, if ever, occurs.

Harvest of this cartilage may be undertaken by a pre- or postauricular approach. In the pre-auricular approach, an incision is made just inside the antihelical fold and is therefore hidden by a shadow. Although we prefer the posterior approach, others prefer the anterior approach.

If the patient has one ear that protrudes more than the other, then the cartilage should be harvested from that side. If the patient sleeps on one side of the head, then the cartilage should be removed from the contralateral side.

Using 1% xylocaine solution with 1:100,000 epinephrine, the surgeon “hydrodissects” the skin of the concha cavum and cymba from the underlying cartilage. Subperichondreal injection of local anesthetic on the anterior surface of the conchal bowl facilitates dissection of the skin off the cartilage. The posterior surface is also injected with local anesthesia.

To proceed with the anterior approach, the surgeon may outline with a marking pen an incision that follows the outer edge of the cavum and cymba concha. This incision should be placed along the portion of the concha that is vertically oriented in relation to the lateral aspect of the skull. Then, the incision is made with a #15 blade, and the surgeon elevates the skin and perichondrium from the underlying cartilage. Dissection proceeds using appropriate scissors and also bluntly with cotton-tip applicators. Care is taken not to damage the soft auricular cartilage, which can tear. The dissection stops short of the cartilage of the external auditory canal.

The radix helices should be preserved. If the entire conchal bowl in excised, the auricle usually settles slightly closer to the head.

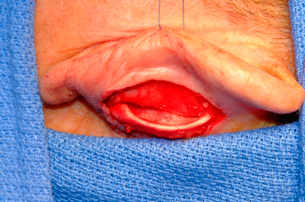

Figure 4 In the postauricular approach, an incision is made postauricularly in the skin overlying the eminentia of the concha. The skin-soft tissue envelope is elevated over the eminetia and the cartilage is incised, being careful to preserve an adequate amount of cartilage along the antihelical fold. The anterior skin and soft tissue are elevated in the subperichondrial plane and the cartilage is excised.

The surgeon dissects out the desired piece of cartilage and leaves the underlying muscle behind (perichondrium remains adherent to the posterior surface of the cartilage). Avoiding deep dissection into the soft tissue minimizes bleeding.

After perfect hemostasis is achieved and the wound has been irrigated, the incision is closed. Commonly a 6-0 nylon running vertical mattress suture is used, although one may also close the incision with interrupted vertical mattress sutures. Special care is taken to avoid overlap of the skin edges. A bolster dressing of Telfa, dental roll, or other suitable material is placed into the concha and sutured into position to decrease the risk of hematoma. No residual deformity of the pinna is expected with this approach. In the postauricular approach, an incision is made postauricularly in the skin overlying the eminentia of the concha. The skin-soft tissue envelope is elevated over the eminentia, and the cartilage is incised, being careful to preserve an adequate amount of cartilage along the antihelical fold. The anterior skin and soft tissue are elevated in the subperichondrial plane and the cartilage is excised.

AURICULAR CARTILAGE: APPLICATIONS

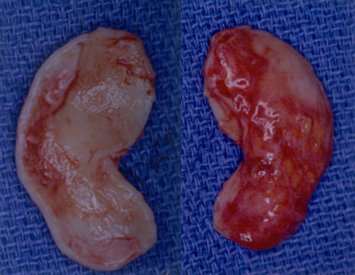

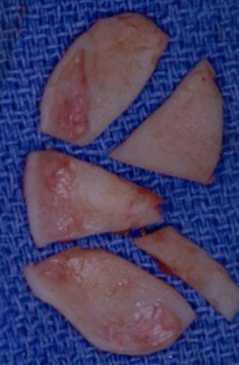

Although each auricular cartilage graft must be carved in such a fashion as to meet the specific needs of the patient, considerable grafting requirements can be fulfilled by one piece of ear cartilage if carving of the cartilage is well planned. In this patient example, two alar batten grafts, a tip graft, a columellar strut, and additional grafting materials were available (Fig. 5). Due to the patient’s relatively thin skin, a layer of soft tissue was left on the posterior surface. Indeed, if the patient has thin nasal skin, then the surgeon may wish to leave a portion of soft tissue on the posterior surface of the auricular cartilage. This allows some additional camouflage and also provides for more rapid tissue adhesion.

Figure 5 The patient shown here had nasal obstruction and nasal aesthetic abnormality. Note especially problems at the nasal tip, with tip bossae, and a collapsed nasal valve. (A,C,E) Preoperative. (B,D,F) Postoperative. The patient’s auricular cartilage is shown both (G) before and (H) after carving of the cartilage.

In each of the next two patient examples, alar batten grafts, a dorsal onlay graft, tip graft, and a strut were carved from single auricular cartilage grafts (Figs. 6, 7).

Figure 6 This patient underwent prior rhinoplasty with overresection of the dorsum and persistent overprojection of the nasal tip. To create a more harmonious appearance, the tip was deprojected with excision of the lower lateral cartilages at the dome, and the nasal tip was resupported with a tip graft. Dorsal onlay grafting and reconstructive grafting of the nasal sidewalls were undertaken.

Figure 6 (continued) (E) The carved auricular cartilage is shown.

Figure 7 (A)This patient had saddle nose and a large septal perforation after septorhinoplasty as well as an aging ptotic nose. (B) A single auricular cartilage graft was used for dorsal onlay grafting, alar batten grafting, nasal plumping grafts, and a columellar strut.

The saddle nose is a common problem seen after trauma and after misadventures in rhinoplasty. In moderate deformities, either single or multilayered cartilage grafts can be undertaken. When septal cartilage is not available, auricular cartilage is the senior author ‘ s preferred graft material (Fig. 8).

Figure 8 When onlay grafting is placed beneath the soft tissue envelope, great care must be taken so that the edges of the graft are smooth and also that the graft is not too wide; otherwise, the edges may be palpable or visible. In this patient example, a double-layered cartilaginous onlay graft was used. This was wrapped in Alloderm due to the patient’s thin skin. (A) Preoperative. (B) Postoperative.

We have found that the portion of cartilage along the antihelical rim is especially suitable for dorsal grafting due to the relatively flat shape of this cartilage. Grafts may be laminated or layered to increase the size of the dorsal augmentation when needed. In this patient example, a double-layered cartilaginous onlay graft was used (Fig. 8). This was wrapped in Alloderm due to the patient’s thin skin. When onlay grafting is placed beneath the soft tissue envelope, great care must be taken so that the edges of the graft are smooth and also that the graft is not too wide; otherwise, the edges may be palpable or visible.

In some cases of severe dorsal collapse, structural auricular cartilage is not appropriate, and rib graft or cranial bone graft for an intercalated L-strut reconstruction is necessary. Irradiated rib grafts have also been described for this use.

Alar batten grafts are commonly needed in revision rhinoplasty. 20 This is due to the unfortunately too frequent problem of overresection of the lateral crus, resulting in weakness of the lateral nasal sidewall with re-traction, especially on inspiratory effort. Auricular cartilage is especially well suited to alar batten grafting due to the slight curvature of its contour. Alar batten grafts are designed to stiffen and hold the flaccid ala laterally and are well described in the literature. The graft is positioned in the supraperichondrial plane but in a non-anatomic position along the nostril rim extending to the pyriform aperture (Fig. 9). In more severe cases of alar retraction, composite grafts of auricular cartilage and skin may be required.

Figure 9 (A) This patient had nasal surgery after a nasal fracture as a young adult. He complained of nasal breathing and has severely pinched narrow nasal valves and nasal valve collapse. (B) Large alar batten grafts were placed, improving the strength and appearance of his nasal sidewalls.

At times, alloplastic implants must be removed when they extrude through the skin, cause pain, or extrude through the nose. In these cases, these grafts can be replaced by auricular cartilage (Fig. 10).

Figure 10 (A,B)This patient had an alloplastic implant placed, which became infected.The infected implant caused a cutaneous fistula and destruction of nasal tip soft tissue.

DISCUSSION

Although revision rhinoplasty can often be accomplished in a simple, direct fashion with minimal need for complicated reconstructive grafting, at times the patient’s problems require more complex surgery with significant structural and reconstructive grafts. Unfortunately, the ideal nasal implant, natural or artificial, does not yet exist, and so the reconstructive surgeon must select a material that fulfills the needs with the most minimal morbidity. We feel that the cartilage autograft fulfills these criteria better than any other currently available material. We have found, as have others previously, that cartilaginous autografts can be used to correct a wide variety of nasal defects with gratifying results and without major complication. Until an ideal implant is identified, cartilage autografts remain our nasal reconstructive material of choice.

REFERENCES

- Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty: The Art and the Science. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997

- Tardy ME, Toriurni DM. Philosophy and principles of rhinoplasty. In: Cummings C, ed. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2nd ed. Mosby-Year Book; 278-294

- Kamer FlV’I, Pieper PG. Revision rhinoplasty. In: Bailey B, ed. I Iead and Neck Surgery—Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1998

- Johnson C;\9 Jr, ‘ Toriumi DM. Open Structure Rhinoplasty. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1990

- Lohuis PJ, Watts Sj, Vuyk I ID. Augmentation of the nasal dorsun using Gore-Tex: intermediate results of a retrospective analysis of experience in 66 patients. Clin Otolaryngol 2001;26(3):214-217

- Godin MS, Waldman SR, Johnson CM Jr. Nasal augmentation using Gortex: a 10-year experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg 1999;1(2):118-121

- Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ. Augmentation rhinoplasty: dorsal onlay grafting using shaped autogenous septal cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;86(1):39-45

- Metzinger SE, Boyce RG, Rigby PL, Joseph JJ, Anderson JR. Ethmoid bone sandwich grafting for caudal septal defects. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1994;120(10):1121-1125

- Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger RY, Key M. The cartilaginous pollybeak: etiology, prevention, and treatment. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6(2):113-120

- Tardy ME, Brown R. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose. New York: Raven Press; 1990

- Larrabee WE, Makielski KH. Surgical Anatomy of the Face. New York: Raven Press; 1983

- Kotler HS, Tardy ME. Reconstruction of the outstanding ear (otoplasty). In: Ballenger JJ, Snow JB, eds. Otorhinolarngology Head and Neck Surgery, 15th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams &Wilkins; 1996;989-1002

- Toriumi DM, Becker DG. Rhinoplasty Dissection Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lipppincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999

- Tardy ME, Dennenv J, Fritsch MI I. The versatile cartilage autograft in reconstruction of the nose and face. Larvngoscope1985;95:523-532

- Tardy ME, Schwartz M, Parras G. Saddle nose deformity: autogenous graft repair. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6(2):121-134

- Wang TD. Aesthetic structural nasal augmentation. ()per Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1990;10:50-54

- Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty and rib grafts: evolving a flexible operative technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;94(5):597-611

- Gunter JP, Clark CP, Friedman RM. Internal stabilization of autogenous rib cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty: a barrier to cartilage warping. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;100(1):161-169

- l\lurakami CS, Cook TA, Guida RA. Nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991;117:327-330

- Toriumi DM, Josen J, Weinberger MS, Tardy ME. Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:802-808

- Tardy ME, Toriumi DM. Alar retraction: composite graft correction. Facial Plast Surg 1989;6(2):101-107