Key Points:

- The over-resected nose or native under-projected nasal dorsum can be augmented with alloplastic or autologous implants, with autologous implants being more preferred due to their safety, biocompatibility and long-term survival.

- The diced cartilage fascia graft has been the preferred method for dorsal augmentation for several years by the lead author (P.N.), but the diced cartilage glue graft is gaining increased popularity.

- The diced cartilage glue graft (DCGG), made of diced septal, auricular or costal cartilage and fibrin glue, is a versatile, safe, predictable and customizable option to augment the nasal dorsum.

- Studies have shown that fibrin glue increases chondrocyte survival and proliferation and improves stability of the diced cartilage.

Synopsis:

The over-resected nose or native under-projected nasal dorsum can be augmented with alloplastic or autologous implants, with autologous implants being more preferred due to their safety, biocompatibility and long-term survival. The diced cartilage fascia graft has been the preferred method for dorsal augmentation for several years 1,2, but the diced cartilage glue graft (DCGG) is gaining increased popularity 3,4,5,6,7. The DCGG, made of diced septal, auricular, or costal cartilage and fibrin glue, is a versatile, safe, predictable and customizable option to augment the nasal dorsum 4,5. Studies have shown that fibrin glue increases chondrocyte survival and proliferation and improves stability of the diced cartilage 4,8. The long-term clinical data on the DCGG shows that these grafts are stable over time with rare resorption or need for surgical revision 9.

Introduction

Over the years, multiple techniques have been described to augment the over-resected or under-projected nasal dorsum. The diced cartilage glue graft (DCGG) is a safe, versatile and customizable option that uses the patient’s native cartilage to create a natural and predictable result. In this chapter, we describe the history, surgical technique and nuances of using the DCGG in rhinoplasty.

Dorsal Augmentation Techniques in Rhinoplasty

Alloplastic Implants

From the early days of rhinoplasty, surgeons have been searching for the optimal material to augment the surgically over-resected dorsum and the native under-projected dorsum. Alloplastic implants, including Silastic, expanding polytetrafluorethylene (Medpore; Stryker) and porous polyethylene (GORE-TEX; W.L. Gore & Associates) have been used successfully for some time and continue to be the implant choice for some surgeons 10. However, these synthetic materials can have complications including infection and extrusion and are not ideal. Despite these risks, in Asia, alloplastic implants continue to be widely perceived as a viable option for dorsal augmentation 4,5.

Autologous Implants

Over the past several decades, there has been a trend toward the use of autologous materials for dorsal augmentation. The benefits of autologous tissue includenormal consistency, flexibility, long-term survival, relative resistance to infection and excellent biocompatibility.

Free Cartilage Grafts

The use of solid cartilage grafts has the benefit of low resorption rate but the downside of increased visibility, warping and stiffness, especially in thin skinned patients. Diced cartilage, first described by Young in the 1940s, can be placed in the nose without any wrapping material 4. These grafts have the benefit of a smooth conformation to the lateral nasal wall without visibility; however, these grafts can be visible if large in size. There are also the theoretical risks of aberrant dispersion and resorption.

“Turkish Delight” and Diced Cartilage Fascia Graft

In 2000, Erol first described the “Turkish Delight,” which consisted of diced cartilage wrapped in Surgicel (Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J[ES1] .). This graft was described as pliable with minimal postoperative visibility and reabsorption 11. Daniel adopted this technique and used this graft in several of his patients, but he later abandoned it after noticing a high rate of resorption. He then modified this procedure by wrapping the diced cartilage in a temporalis fascial envelope, called the diced cartilage fascia (DCF) graft.

He performed a prospective study of fifty patients undergoing rhinoplasty using diced cartilage wrapped in Surgicel verses temporalis fascia, where he reviewed postoperative resorption rates and histologic sections.

The patients who had diced cartilage wrapped in Surgicel had increased resorption rates and demonstrated a foreign body reaction, which was not seen in the DCF population 1. Several studies followed which showed a similar success rate of DCF grafts 2,12.

The use of the DCF graft subsequently became widely adopted for dorsal augmentation. Figure 1 a/b shows an intraoperative photo of a DCF graft used to augment an over-resected nasal dorsum. Figure 2 a/b shows a pre- and postoperative right profile view of a patient who underwent DCF graft to correct a saddle nose deformity.

Reported benefits of the DCF graft are that it is easy to mold when in place over the nasal dorsum, has little to no resorption and does not require over-correction. Downsides include difficulty to assess the dorsal height, tendency to over-graft the radix (because diced cartilage may spill into this space when the dorsum is compressed during molding) and risk of long-term edema 3. In the lead author’s practice (P.N.), we have seen that the DCF graft can migrate or contract during the three-dimensional healing of the skin, which can result in irregularities such as fullness, shrink wrapage, focal contraction and curvature (Figures 3 and 4).

Others have noted similar concerns, in that the DCF graft tends to acquire an oval or kidney-shaped cross section that is not anatomic, with a resultant visible groove parallel to the dorsum on either side of the graft 4. Infection is also a risk, although uncommon. In our practice, we had a patient who previously had an infected silicone nasal implant which was removed and replaced by a DCF graft. Three years later she subsequently developed a chronic infection of her DCF graft requiring removal, washout and replacement of the graft. Another downside is that the DCF graft technique requires harvesting temporalis fascia, which is a second procedure and prolongs the operating room time and patient recovery.

Diced Cartilage Glue Graft

In 2011 at the Advances in Rhinoplasty meeting in Chicago, Illinois, Tasman introduced his technique for making a graft using diced cartilage combined with human tissue sealant to augment the nasal dorsum, which became known as the “Tasman Technique”. Baker (2012) adopted this methodology and published an elegant detailed description of his surgical approach in a series of patients. Baker cites the theoretical advantages of using human tissue sealant rather than avascular fascia to bind the diced cartilage, including more rapid revascularization and better adherence to adjacent bone and cartilage 1. In his patient population, he noted considerably less long-term edema of the nose using the “Tasman Technique” compared with use of the DCF graft. Later than year, Tasman described his technique and published the results his series of 28 patients that had been treated with what he called a DCGG. He used the DCGG to augment the full length of the nasal dorsum in 16 patients and partial length in 12 patients. He reported follow-up data ranging from 6 to 22 months. In 10 of these patients, he performed postoperative sonographic morphometry to measure the graft thickness in the early and late (greater than one year) postoperative period, which showed low resorption rates and good stability over time. In two patients, he performed a minor revision procedure under local anesthesia for a visible irregularity. In these two patients, he collected DCGG fragments for histological analysis, which showed the cartilage embedded in a sleeve of connective tissue with intact cut edges and minimal to no signs of cartilage resorption. Tasman does note that the largest reductions in sonographic cross sections were seen in an early patient, in whom proportionally more fibrin glue was used. This highlights the importance of surgical experience in achieving optimal patient results 4.

In addition to Tasman and Baker, over the next several years other surgeons describe their experience with using diced cartilage with this fibrin sealant scaffold. Brasilia et al. (2012) advocate for mixing diced cartilage with fibrin glue in a 1mm syringe to create a gelatinous material which they call the “nougat graft.” They implant the gelatinous preparation through the same syringe to augment multiform defects of the radix, dorsum, peri-pyriform, infralobule and lateral nasal wall 6. Stevenson and Hodgkinson (2014) call it a “cartilage putty” graft in their series of 19 patients who had complex or revision rhinoplasty surgery with use of the graft. Their patients had no graft absorption or requirement for revision surgery 7.

Review of Fibrin glue and its use in cartilage grafting

Fibrin glue is a topical biologic adhesive consisting of a combination of concentrated human fibrinogen, thrombin and calcium chloride. The surgical utilization of the hemostatic and adhesive properties of fibrin glue dates back to World War I. It can be employed by virtually every surgical specialty and is well documented in the fields of cardiovascular surgery, ENT and neurosurgery. The action and final effect of the product imitates the final stages of coagulation and relies on careful surgical technique. The adhesive strength is directly proportional to the concentration of fibrinogen 13.

Methods of application of fibrin glue have evolved over time. Tisseel (Baxter International Inc., Newbury, Berkshire, UK) is a commercially available product that consists of a dual chamber application syringe. One side contains fibrinogen and factor XIII, derived from pooled human plasma that has undergone negative viral testing. The other chamber contains bovine thrombin and calcium chloride. These components are mixed together to activate the product upon administration. Tisseel is FDA approved in the US for its hemostatic properties and sealant properties 14.

Reports have shown that adding fibrin to cartilage provides a scaffold for enhanced chondrocyte proliferation and cartilaginous tissue formation to improve cartilage viability. Kaufman and colleagues (2004) demonstrated enhanced cartilage survival with the addition of a fibrin sealant, using an animal model. They demonstrated reduced resorption of morselized cartilage grafts and reduced chondrocyte dropout rates 8. Tasman showed similar findings when he performed revision surgery on two of his patients and collected a segment of the previously placed DCGG for histological analysis. The chondrocytes appeared to be vital and formation of small clones consisting of clusters of more than 4 chondrocytes was seen, indicating cartilage regeneration 4. Similar benefits of fibrin glue have been presented in association with skin graft survival 15. Stevenson and Hodgkinson reported improved alveolar bone graft survival in cleft patients when fibrin glue is used 7.

Surgical Technique

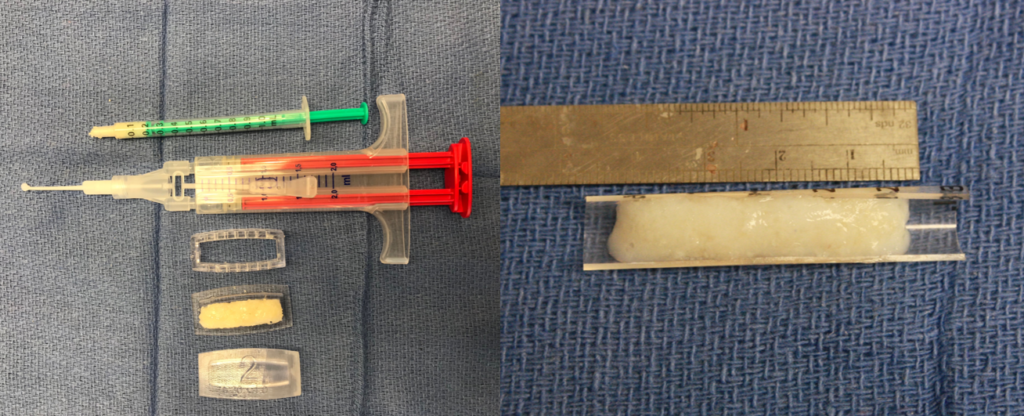

In the lead author’s practice (PN), the use of fibrin glue to make a diced cartilage glue graft (DCGG) has largely replaced use of the diced cartilage fascia graft for reconstructive rhinoplasty. Autologous septal, conchal or costal cartilage is harvested and finely diced with a straight razor blade to make finely diced cartilage (FDC). The FDC is inserted into a one cc syringe and excessive water is siphoned. The FDC is then inserted into a preformed plastic mold (Yong Ju Jang™), which comes in various sizes (Figure 5a). Alternatively, a three cc syringe cut in half in the sagittal plane can be used as a scaffold (Figure 5b). To make the graft, first a thin layer of FDC is applied, followed by a few drops of fibrin glue. A total of three layers of cartilage and fibrin glue are applied, usually using a total of one cc of cartilage. Between each cartilage application, a cottle or other blunt instrument is used to pack the cartilage and squeeze out excess fibrin glue. The mold has small holes on the sides to allow excess glue to be eliminated. After about 10-15 seconds, the graft is ready to be removed from the mold and is placed onto a carving board.

At this point the cartilage is still very moldable and pliable and can be sectioned and or flattened into the appropriate shape for nasal reconstruction. The grafts are then cut and molded to the desired shape and size. The grafts can be inserted through both an open or closed approach. An Aufricht retractor is used to retract the nasal skin, and the graft is inserted using a bayonette forcep into the appropriate location. A cottle elevator is then used to contour the graft to the nasal dorsum. The graft can then be further molded and contoured in situ using a cottle elevator.

Multiple Uses of the Diced Cartilage Glue Graft

The DCGG can be used in primary and revision rhinoplasty for multiple purposes. The most common method cited in the literature and in our practice is for partial or total dorsal reconstruction. For these patients, the length of the graft can be varied and tapered to restore a smooth, straight and strong nasal profile, as seen in Figure 6a/b and Figure 7a/b/c.

The graft is also useful after primary hump reduction to treat an open roof deformity and possibly avoid performing lateral osteotomies to prevent an overly narrow nose and preserve width of bony nasal sidewalls 5. Figure 8 demonstrates a patient in our practice who underwent primary rhinoplasty with hump reduction and use of the DCGG to contour the open roof deformity for this purpose.

As discussed by Brasilia et al. (2012), the DCGG can also be used augment multiform defects of the radix, dorsum, peri-pyriform, tip, infralobule, facet and lateral nasal wall. Figure 9a/b/c shows a patient who had a graft fashioned to soften the nasal tip. A similar patient is depicted in Figure 10a/b, who underwent revision rhinoplasty with DCGG graft placement to radix, paramedian dome and supratip. Figure 11a/b[ES2] shows a patient who had a polly-beak deformity and under-projected, over-rotated nasal tip, who underwent revision rhinoplasty with DCGG placement to the radix and infratip/dome/facets.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Diced Cartilage Glue Graft

There are many advantages for use of the DCGG. It is pliable, customizable and easy to use. It can be used for large and small defects, with the primary limitation being cartilage availability. It is particularly useful in patients with thin skin, where is can create a smooth contour with reduced visibility compared to more solid cartilage grafts. It eliminates the need to harvest fascia, which decreases intraoperative time and postoperative recovery.

Like any technique or procedure, there are also disadvantages with the DCGG. It requires a certain level of experience to create an optimal graft. Tasman reported that he used excessive fibrin glue in his earlier surgical patients, and he noticed increased graft resorption in these individuals compared to his later patients 4,5. Over time he refined his techniques and used only the amount of glue needed to bind the cartilage for manipulation, with improved postoperative results. Touriumi notes that these grafts lack structural support, which may decrease the appearance of the ideal dorsal aesthetic lines that are present with the natural nose or a firmer cartilaginous graft 16. Another technical consideration is the need for a larger dissection pocket to achieve good graft position, which may be difficult from an endonasal approach. There are also risks of using fibrin glue including thromboembolic events, hypersensitivity reaction, anaphylaxis and theoretical disease transmission. It should only be applied topically to tissue and not injected 13. Finally, there is a cost to consider when using fibrin glue. These factors must all be considered when choosing this method to augment the nose.

Conclusion

Over the last decade the DCGG, which has several names including the “Tasman Technique”, “nougat graft” and “cartilage putty” has had growing use and implications in rhinoplasty. Studies have shown that using fibrin glue to bind diced cartilage results in improved cartilage survival and decreased resorption resulting in versatile and predictable long-term result. In many practices, the DCGG has replaced used of the popular DCF graft. However, there are downsides of the graft that must be considered including cost, surgical learning curve and the risk of infection and hypersensitivity reaction. With this being a newer technique in the long history of rhinoplasty, more studies must be conducted to assess the long-term viability of the grafts.

References

- Daniel RK, Calvert JW. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2004 Jun 1;113(7):2156-71.

- Kelly MH, Bulstrode NW, Waterhouse N. Versatility of diced cartilage-fascia grafts in dorsal nasal augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6):1654-1659.

- Baker SR. Diced cartilage augmentation: early experience with the Tasman technique. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2012 Nov 1;14(6):451-5.

- Tasman AJ, Diener PA, Litschel R. The diced cartilage glue graft for nasal augmentation: Morphometric evidence of longevity. JAMA facial plastic surgery. 2013 Mar 1;15(2):86-94.

- Tasman AJ. Advances in nasal dorsal augmentation with diced cartilage. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2013 Aug 1;21(4):365-71.

- Brasilia R, Tambasco D, D’Ettorre M, Gentileschi S. “Nougat graft”: diced cartilage graft plus human fibrin glue for contouring and shaping of the nasal dorsum. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 Nov 1;130(5):741e-3e.

- Stevenson S, Hodgkinson PD. Cartilage putty: a novel use of fibrin glue with morselized cartilage grafts for rhinoplasty surgery. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2014 Nov 1;67(11):1502-7.

- Kaufman MR, Westreich R, Ammar SM, Amirali A, Iskander A, Lawson W. Autologous cartilage grafts enhanced by a novel transplant medium using fibrin sealant and fibroblast growth factor. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2004 Mar 1;6(2):94-100.

- Tasman AJ. Replacement of the nasal dorsum with a diced cartilage glue graft. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2019 Feb;35(01):053-7.

- Peled ZM, Warren AG, Johnston P, Yaremchuk MJ. The use of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty surgery: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):85e-92e18317090.

- Erol, O. O. The Turkish delight: A pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105: 2229, 2000.

- Brenner KA, McConnell MP, Evans GRD, Calvert JW. Survival of diced cartilage grafts: an experimental study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(1):105-11516404256

- Brennan M. Fibrin glue. Blood reviews. 1991 Dec 1;5(4):240-4.

- Tisseel [Fibrin Sealant] for Surgical Care. Retrieved from Baxter website January 1, 2020. https://advancedsurgery.baxter.com/products/tisseel

- L.J. Currie, J.R. Sharpe, R. Martin. The use of fibrin glue in skin grafts and tissue-engineered skin replacements: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg, 108 (2001), pp. 1713-1726

- Toriumi DM. Discussion: combined use of crushed cartilage and fibrin sealant for radix augmentation in Asian rhinoplasty. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Feb 1;135(2):301e-2e.

Disclosure Statement: Dr. Paul Nassif and Dr. Erin Smith have no relevant financial or conflicts of interest to disclose. No funding was received for this article.