Introduction

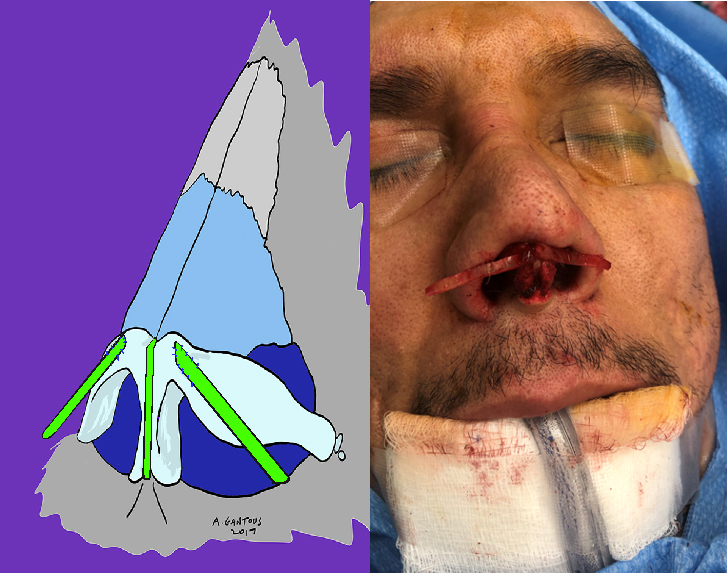

Generations of rhinoplasty surgeons have struggled to find a way to correct and consistently manage saddle deformities of the nasal dorsum. These deformities of the nasal framework can lead to devastating emotional and psychological effects in patients1. The more common causes that can lead to the development of these severe dorsal contour irregularities are traumatic, iatrogenic, drug induced, autoimmune and congenital (Figs. 1-5).

The degree of deformity is dependent on the extent and location of the septal defect that invariably accompanies the collapse of the nasal dorsum (Fig. 6).

The septal loss can be cartilaginous, bony or both. This can occur with or without the presence of a septal perforation.

The aesthetic and functional defects that are found can range from a loss of dorsal height, to foreshortening of the nose with tip deprojection and retraction of the nasolabial angle, to almost complete loss of dorsal height and retraction into the maxilla1.

The severity of the saddle deformity will determine the necessary method of reconstruction. Mild deformities may only require some form of dorsal augmentation or camouflaging, but moderate and severe deformities need to be managed by applying the principles of structural rhinoplasty2.

This type of augmentation rhinoplasty has been historically performed using autogenous grafts, alloplastic materials and homografts3. In general, autogenous grafts are considered the gold standard for nasal reconstruction due to their relative ease of use, high acceptance rate, durability and virtual lack of an immunological response4. Autogenous cartilage can be easily harvested from the nasal septum or the auricle for most routine rhinoplasty cases. Autogenous bone grafts include calvarial bone, iliac crest and rib bone.

These grafts have been used extensively in craniofacial reconstruction, but their use in the nose has been criticized for resulting in unnatural stiffness, potential fracture of the grafts, difficulty in fixating the grafts and increased risk of resorption5. They are considered a second choice to cartilage grafts. Alloplastic materials such as solid silicone, Gore-Tex and Medpor among others have been extensively used due to their availability, ease of use, lack of resorption and lack of donor morbidity. These implants have been shown to have higher rates of infection and extrusion which can occur at any point in time and necessitate their removal6. Homografts such as cadaveric irradiated rib cartilage and acellular dermis are used by many surgeons with reports of consistent good results7, 8. However, the reported higher resorption rates, the fear of disease transmission, the possible lack of patient acceptance and, in the setting of universal health care, the high cost of the grafts limit their use4.

Managing these severe deformities of the nose can be extremely challenging and the need for extensive structural grafting is invariably necessary. The nasal septal cartilage is often absent or very deficient and conchal cartilage does not provide the desired structural support. For these reasons, for most surgeons, the use of costal cartilage has become the new gold standard in these cases. This graft is readily available, large amounts can be harvested and is quite versatile due to the fact that it can be easily cut, shaped and fixed in place.

Surgical goals and principles

In reconstructive nasal surgery one normally wants to attain certain goals and abide by some basic principles. One always strives to restore nasal function and nasal cosmesis as best as possible. One tries to recreate the normal anatomy if feasible, provide adequate support and replace missing tissue with similar tissue9-11.

In cases where there is a severe or catastrophic saddle deformity, the degree of the deformity and the extent of the soft tissue integrity will determine the best method of reconstruction. The standard principles that are applied for nasal reconstruction when dealing with traumatic or oncological deformities (a three-layer reconstruction) cannot be fully implemented in certain cases. In deformities caused by cocaine or granulomatous vasculitis where one finds defects of the internal lining that can range from granulomas to a total absence of the septum, the reconstruction is best directed towards improving the nasal airflow and appearance1.

The degree of nasal collapse and the integrity of the skin-soft tissue envelope (S-STE) will guide the grafting choices, the timing of surgery and the foreseeable need for further operations.

I have used a variety of grafting materials over the years including calvarial and iliac crest bone, radiated rib cartilage and auricular cartilage. I now exclusively use autologous rib cartilage as my main source of structural grafting material due to its versatility and ease of use. Surgeons should be comfortable with a range of surgical techniques when addressing these complex cases. The options that one normally chooses may not be attainable in certain cases so one should be prepared to resort to other techniques that may not be routine.

Surgical planning

Strong and long-lasting structural support is the cornerstone of all saddle nose reconstruction. As mentioned above, autologous cartilage grafts are the choice material to obtain this, but other grafting material is sometimes required.

In general, the three basic considerations are to obtain vertical support, longitudinal support and reconstruction and lateral wall strength optimization. Sometimes, contour grafting is then required when the structural support provided does not meet these needs.

Surgical techniques

There exist many ways of harvesting costal cartilage and most are acceptable. It is important to be able to obtain the necessary amount of tissue and to minimize surgical morbidity such as postoperative pain and long-term discomfort (Video 1)12.

Video 1: Rib cartilage harvest technique.

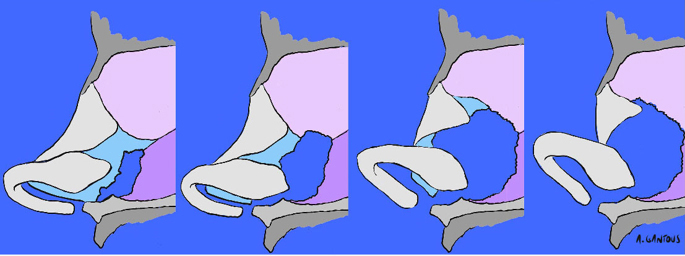

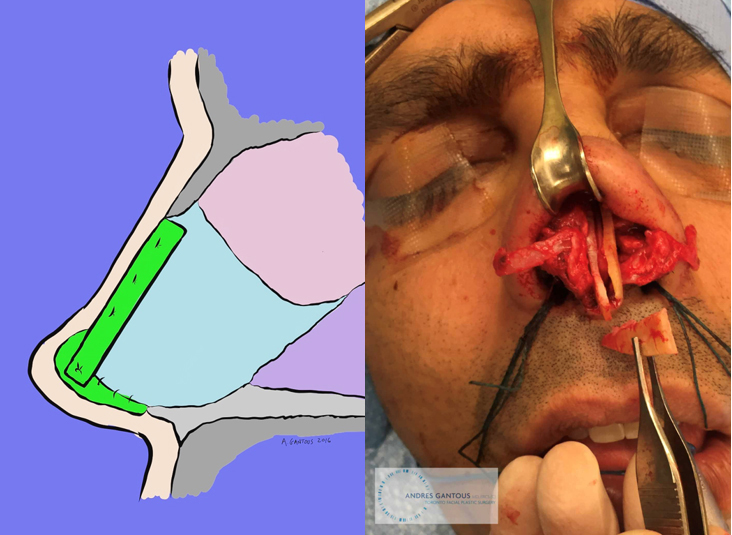

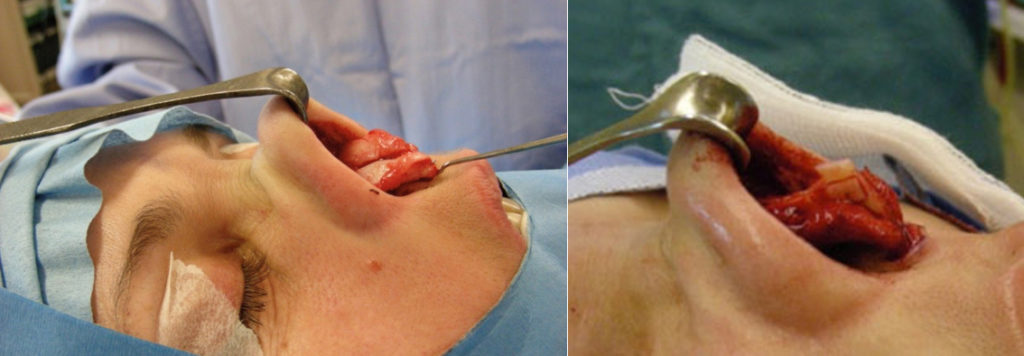

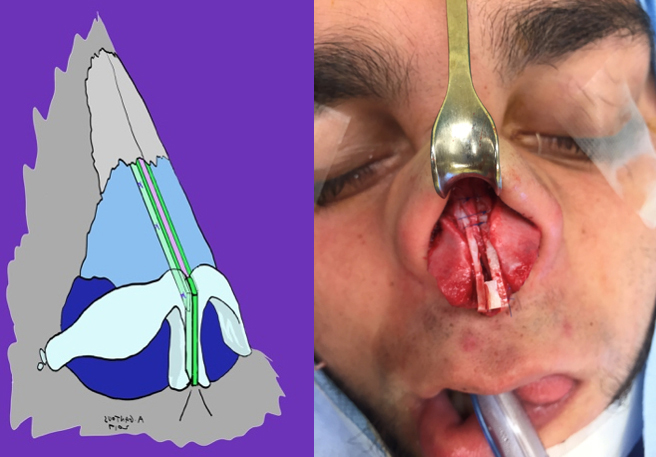

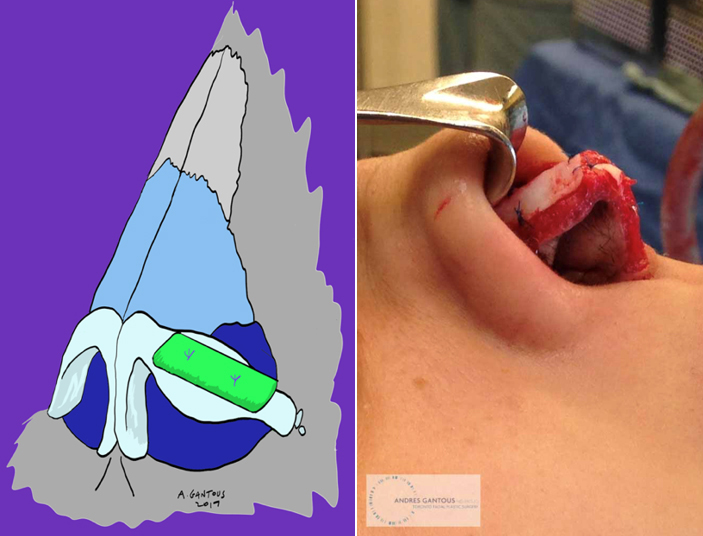

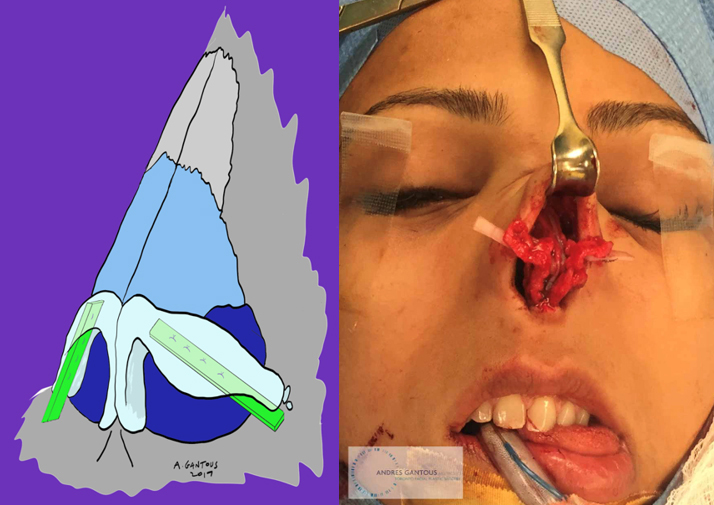

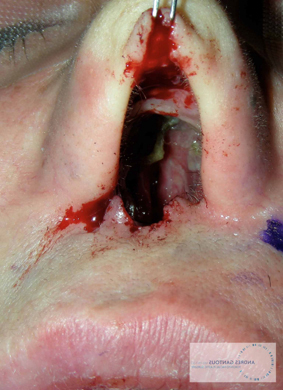

Vertical support is obtained through a variety of grafting techniques. The more commonly used are strong columellar struts, caudal septal extension grafts (SEG) (Fig. 7) and septal replacement grafts (SRG) (Figs. 8-9). All of these can be easily carved from costal cartilage.

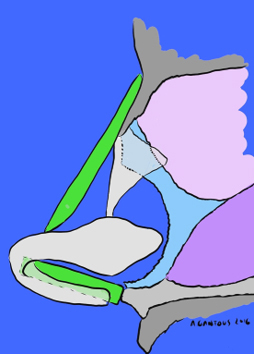

Longitunidal support can be obtained with the use of extended spreader grafts that can span the lower two thirds of the nose if necessary (Fig. 10).

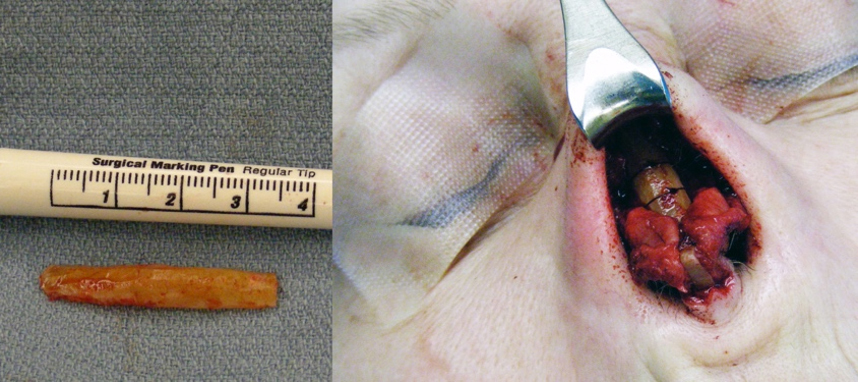

The cantilevered dorsal onlay graft has been a workhorse of nasal reconstruction and can be a good option in most cases of saddle nose reconstruction (Figs. 11-12). These grafts can be sutured to the nasal bones, fixed with a K-wire or a surgical screw or simply allowed to adhere to the underlying nasal bones in some cases.

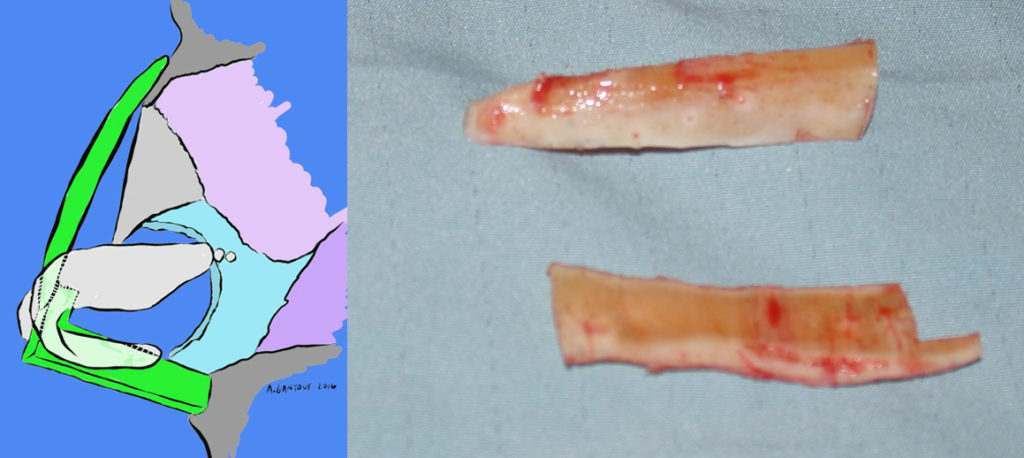

L-grafts are hinged dorsal and vertical grafts or mono-block carved grafts that rebuild the nasal unit. They provide the strongest form of reconstruction, but they do require a lot of grafting material (Fig. 13).

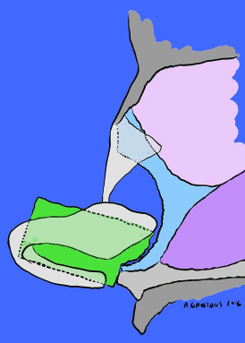

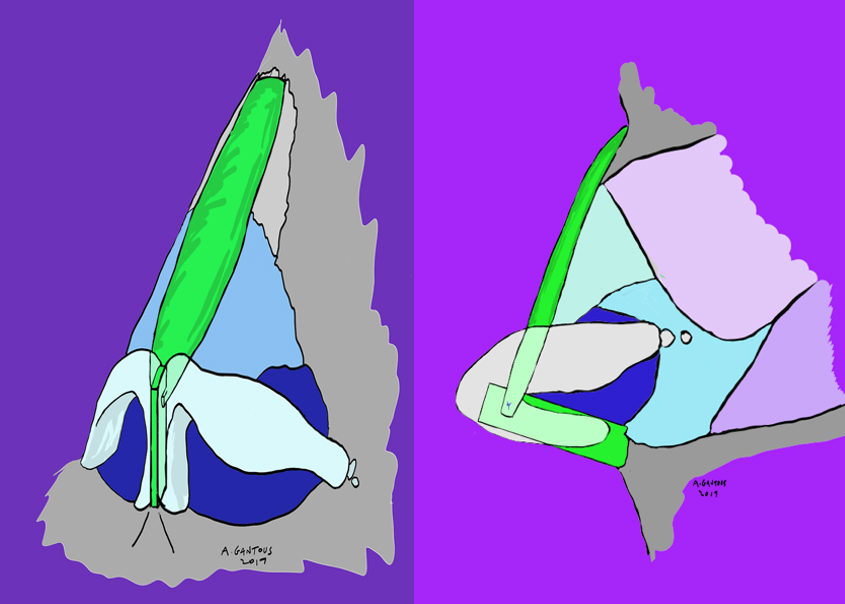

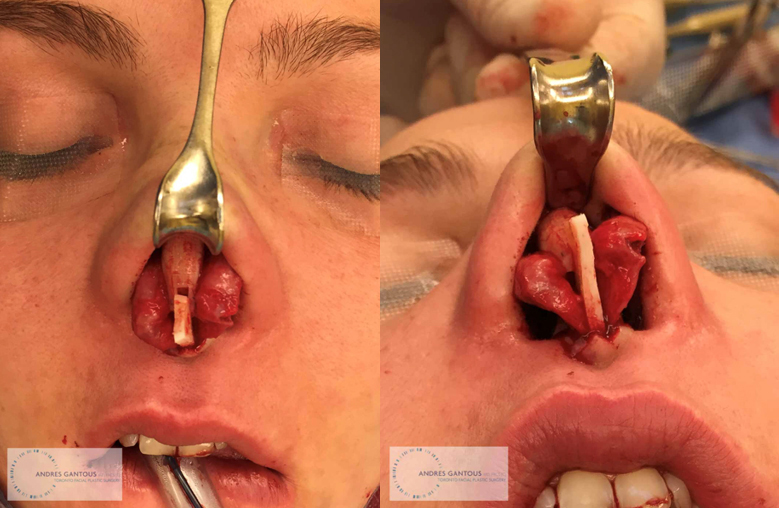

The tongue and groove grafts are hinged dorsal grafts that are a form of an L-graft. They are connected in a tongue and groove manner to the vertical SRG, this allows the dorsal graft to stay in position in a caudal-cephalic direction and the SRG to be supported like if it had extended spreader grafts (Figs. 14-15 and Video 2).

Video 2: Creation and placement of a tongue-in-groove graft.

Lateral wall support is obtained by a variety of means and the exact technique is to be decided based on the needs of the individual nose. The more commonly used grafts are batten grafts, lateral crural underlay grafts and articulated rim grafts. Floating rim grafts can also be used as an extra precaution in some cases, but they do not add sufficient strength on their own in these cases (Figs. 17-18).

Contour dorsal and tip grafting is the last thing to do in these cases. Once the nasal framework has been reconstructed, the need for contour or camouflage grafting is decided. Most of the time, the large dorsal structural grafts that are used suffice to create a proper and cosmetically pleasing result. Sometimes, the S-STE has been injured and may require additional work in order to obtain a better result. The use of soft tissue grafts such as fascia, perichondrium and periosteum are ideal. Toriumi has proposed using microfat impregnated soft tissue augmentation (MISTA) where temporalis fascia grafts are injected with nanofat or microfat and placed over the cartilage grafts and under the damaged S-STE. He has shown promising results13.

When the dorsal grafts don’t provide as much augmentation as desired, contour grafts fashioned from the above materials alone or in combination with morcelized cartilage, diced cartilage and diced cartilage glue grafts are often used to achieve the desired result14 (Fig. 19).

Case presentation and discussion

A 39 years old female presents with a one-year history of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). She noticed progressive collapse of her nasal dorsum, rhinitis, crusting and middle ear disease. She also had lower limb vasculitis. She was treated with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide which controlled her symptoms.

She was found to have a near total collapse of the dorsum, with a severe saddle deformity and foreshortening of the nasal tip. The septal cartilage was absent on palpation and there was no perforation of the mucosa.

A reconstructive rhinoplasty was performed using costal cartilage for reconstruction. An SRG measuring 25 x 10 x 2 mm. was used for vertical support, a 30 mm long cantilevered dorsal cartilage graft was used, and a small cartilaginous contour graft was placed on top of this in the supra tip region. The dorsal grafts were secured with Tiseel TM (Fig.20).

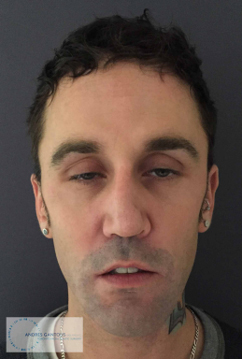

A 60 years old male presents with a history of nasal collapse, right alar collapse, bilateral nasal obstruction for several years. No previous history of nasal surgery and no history of nasal trauma. He admits to cocaine use for several years. He has been drug free for over a year.

He was found to have a moderate to severe saddle deformity. The right ala is completely collapsed, there is a subtotal septal perforation and the posterior nasal cavities are scarred and stenotic.

An L-shaped graft construction was used. A long dorsal onlay graft was supported distally on a segment of the SRG. A fascial graft was put as an onlay graft over the dorsal graft. A lateral crural underlay graft was used to support the right lateral crura. A batten graft was also used for better lateral wall support. A V-Y advancement flap was designed at the melo-labial angle on the right and the nasal ala was released from the cheek. The flap was advanced into the nasal sill area (scarred skin was removed) and the ala attached to the donor site left by the advancement flap. Synechiae and scar tissue were released intranasally and silicone splints were designed and sutured from the nostrils to the choanae (Fig. 21).

A 69 years old male presents with a history of GPA for over 20 years. He has had a progressive collapse of his nose, noticing a complete loss of any dorsal tissue. Has severe nasal obstruction and epiphora.

On examination, the nasal dorsum is below the sagittal plane of the face. There is extreme fore shortening of the nasal tip. The is a near total nasal septal perforation.

Costal cartilage was used to create an SRG with dorsal onlay graft attached in a tongue-ingroove fashion to it. A cartilaginous onlay graft was placed over the dorsal graft at the level of the nasion and another in the supratip area. The dorsal grafts were secured with a K-wire (Fig. 22).

The etiology of the saddle deformity, degree of tissue damage and available grafting options have to determine the method of reconstruction. Many options exist and the surgeon needs to be prepared to modify the surgical plan at any point in these operations. The graft design will change based on the quality and availability of the donor material. The method of graft fixation also will vary depending on the tissues and how the graft(s) fit in the nose. The need for contour grafting is also always different.

Any surgical patient is subject to experience a postoperative complication, but patients with GPA and drug induced damage or vasculitis are at a higher risk of developing problems. Patients with vasculitis require large, strong grafts that can sustain an exacerbation of their disease. Costal cartilage is thus ideal for these reconstructions due to its abundance, ease of harvest and versatility of use. The cartilage needs to be cut and prepared carefully in order to prevent postoperative problems. Despite all possible intraoperative care, sometimes one sees these problems. The more commonly seen issues are infection, graft displacement, cartilage warping and graft resorption (Figs. 23-25). Rare complications such as tissue necrosis can also occur (Fig. 26).

Conclusion

The surgical management of the severe nasal saddle deformity requires grafts that are strong, versatile and that will be able to endure stress and last a long time. As is well known, there is no ideal grafting or implant material. Costal cartilage has been accepted as, probably, the best grafting option in rhinoplasty when the demands for tissue are high.

This type of nasal operation is complex, and the rhinoplasty surgeon must be able to dominate a variety of surgical techniques in order to have satisfactory and predictable results. I believe that, with experience, attention to detail, careful tissue handling and surgical technique, the morbidity, complication rate and surgical time become very acceptable.

Patients suffering from these devastating nasal deformities are incredibly appreciative of the help that is given to them and one is able to improve their quality of life and happiness.

References

- Sepehr A, Alexander AJ, Chauhan N, Gantous A. Detailed analysis of graft techniques for nasal reconstruction following Wegener granulomatosis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg2011;40(06):473–480

- Moshaver A, Gantous A. The use of autogenous costal cartilage graft in septorhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137 (06):862–867

- Adamson PA. Clinical commentary: grafts in rhinoplasty: alloplastic vs. autogenous, clinical challenges in otolaryngology. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;126(04):561–562

- Toriumi DM. Choosing autologous vs irradiated homograft rib costal cartilage for grafting in rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2017;19(03):188–189

- Jackson IT, Choi HY, Clay R, et al. Long-term follow-up of cranial bone graft in dorsal nasal augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102(06):1869–1873

- Genther DJ, Papel ID. Surgical nasal implants; indications and risks. Facial Plast Surg 2016;32(05):488–499

- Kridel RW, Ashoori F, Liu ES, Hart CG. Long-term use and follow-up of irradiated homologous costal cartilage grafts in the nose. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2009;11(06):378–394

- Sherris DA, Oriel BS. Human acellular dermal matrix grafts for rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J 2011;31(7, Suppl):95S–100S

- Toriumi DM. Structural approach to primary rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J 2002;22(01):72–84

- Structure approach in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2005;13(01):93–113

- Adamson PA. Open rhinoplasty. In: Papel ID, Nachlas NE, eds. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1992:295–204

- Chauhan N, Sepehr A, Gantous A. Costal cartilage autograft harvest: inferior strip preservation technique. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125(05):214e–215e

- Toriumi DM. Dorsal augmentation using autologous costal cartilage or microfat-infused soft tissue augmentation. Facial Plast Surg 2017;33(02):162–178

- Tasman AJ, Suárez GA. The diced cartilage glue graft for radix augmentation in rhinoplasty. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2015;17 (04):303–304