Introduction

A saddle nose deformity is characterized by a markedly depressed bony dorsum and an accompanying collapse of the middle nasal vault in relation to the tip and dorsum1. This deformity is the result of a complex interplay of factors leading to the loss of structural support of the nasal septum and upper lateral cartilages, collectively known as the middle vault, and their junction with the bony dorsum and cartilaginous tip Saddle nose deformity can present as one of the more dreaded complications of nasal surgery. Regardless of its cause, management poses one of the more daunting challenges for the reconstructive surgeon.

The etiologies of saddle nose deformity can be quite variable. They include congenital diseases such as Binder syndrome, which is characterized by nasomaxillary hypoplasia with abnormal and deficient nasal bones,systemic diseases such as relapsing polychondritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, sarcoid, and Crohn’s disease2,3. Infectious processes such as septal abscess, leprosy and syphilis tend to affect the middle vault. Cocaine abuse, trauma and prior surgical procedures constitute some of the other factors that cause damage to the mucoperichondrial layer of the nasal septum and resultant cartilage dissolution and saddling1.

Post-operative saddle nose deformity can be caused by a variety of factors including the overzealous use of flat osteotomies, the overuse of rasps, or the overuse of saws. Saddling may occur during or after rhinoplasty when there has been weakening of the dorsal support of the nose. Patients with short nasal bones are at higher risk for this complication. Overresection of the dorsum at the level of rhinion, which has the thinnest soft tissue envelope during dorsal hump reduction, may predispose to disconjugation of the balance between the upper and middle vaults of the nose, thus creating a saddled appearance without an actual weakening of support4.

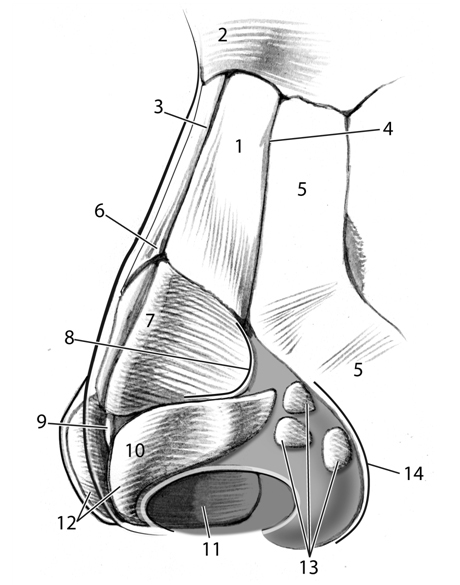

Anatomy

The understanding of the local anatomy and dynamic structural relations of the bony and cartilaginous vaults of the nose is imperative in both the avoidance of producing a saddle nose deformity during nasal surgery and in planning a repair. The nose is commonly assessed and regarded by surgeons as being divided into three components: the upper bony vault, the middle cartilaginous vault, and the lower cartilaginous vault. The bony vault is composed of the paired nasal bones, articulating laterally with the frontal process of maxilla, and superiorly with the nasal process of the frontal bone. In the midline, these paired bones approximate each other and the perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone, which is a component of the nasal septum. At the inferior end of the upper bony vault, the paired nasal bones will meet the upper lateral cartilages of the nasal sidewall. The point in the midline where the paired nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages meet is called the rhinion.

The lower two components of the nose correspond to the areas supported by the upper and lower lateral cartilages respectively. The upper lateral cartilages invariably underlay and are attached to the underside of the nasal bones for a variable distance of 3 to 10 mm. Disruption of this relationship either traumatically or iatrogenically plays a role in middle vault collapse and potential compromise of the airway4. The dimensions and patency of the middle vault will have to be reconstructed in many cases of saddle nose deformity through the application of grafting techniques such as spreader grafts and battons.

The paired upper lateral cartilages are fused with the quadrangular septal cartilage in the midline. The quadrangular cartilage articulates with the perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone superiorly and the vomer inferiorly via a system of fibrous attachments. The cartilaginous septum is attached to the upper lateral cartilages dorsally and proceeds caudally to form the anterior septal angle where it intercalates with the alar cartilages, and inferiorly ends in its attachment to the nasal spine of maxilla at the posterior septal angle. The dorsum of the nose derives most of its strength from the midline continuation of the bony and cartilaginous septum4. During septorhinoplasty, this dorsal support is preserved by the maintenance of adequate caudal and dorsal “struts.”

The lower cartilaginous vault, is shaped by the intricate forms of the lower lateral cartilages, the fibrofatty lateral ala, the caudal septum and the junctions that this compartment makes with the upper lateral cartilages cephalically, the upper lip caudally, and the cheeks laterally. The three main mechanisms of tip support include: the intrinsic strength and resilience of lower lateral cartilages, the attachments of lower lateral cartilages to upper lateral cartilages, and the attachment of the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages to the caudal septum. Many surgical maneuvers during rhinoplasty will disrupt several of these support mechanisms and they must be reconstituted or mimicked if nasal tip position is to be preserved5.

Given a particular osseocartilaginous skeleton, innumerable permutations of external appearance are possible, dictated by the characteristics of the soft tissue envelope. Of course, such variations need to be accounted for by the rhinoplasty surgeon while designing reductive contouring of the dorsal septum to avoid creating a saddle nose deformity.

Aesthetic analysis and preoperative evaluation

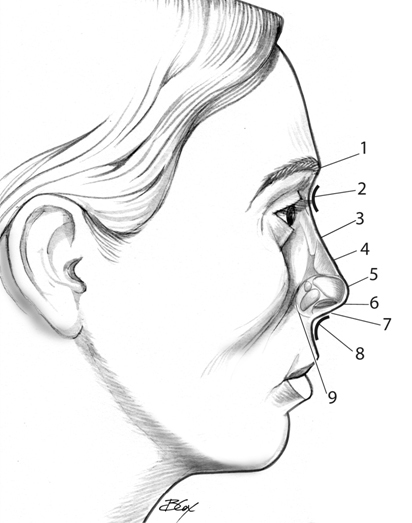

The face and nose are ascertained by their recognizable patterns of light and shadows, subtle convexities, and concavities that are imparted by the form inherent in the combination of the soft tissue cover and influenced by the underlying skeleton. As described below, there are a number of accepted dimensions and relationships that characterize the aesthetic nose.

The nose projects antero-inferiorly from the nasion that corresponds to the suture line between the frontal and paired nasal bones. Clinically this area marks the junction between the forehead and the nasal dorsum and is the origin of the nasofrontal angle. This angle is formed by the relationship between the forehead at the glabella and the nasal dorsum.

The angle normally ranges between 115 to 130 degrees, with females tending to have an angle that falls in the more obtuse limits of that range and with males possessing an angle in the more acute limit6. There are no well-established parameters to determine the correct depth of this angle, however, the dorsum should be of sufficient height to create a distinct anatomical separation of the eyes and give a third dimension to the upper portion of the face6. With the eyes in forward gaze, the nasofrontal angle should intersect a horizontal line originating between the superior lash line and the supratarsal crease. On profile, the nasal dorsum proceeds anterio-inferiorly from nasion towards the tip in a straight or slightly convex fashion4. Ideally the transition from the nasal dorsum to the tip should include a distinct change in the contour of the dorsum, known as supratip break.

In examining the patient in frontal view, the nasal dorsum should be outlined by two slightly curved divergent lines that extend from the medial supracilliary ridges to the tip defining points. This line is known as the brow-nasal aesthetic line. In patients with saddle nose deformity, they tend to have a “washed-out” central facial appearance with a lack of dimension and detail. The nose appears to be in two compartments, with the dorsum appearing flat and dimensionless, and the tip appearing to rise independently from the shallow midface. Frequently, the depressed central face takes the form of an inverted “V” in the frontal view.

The surgeon should also assess dorsal and tip support by both anterior rhinoscopy and digital palpation, including Q-tip examination of internal nasal valves, and tip recoil. The state of integrity of structural supports will greatly influence the methods utilized in the correction of “saddling”7.

The Surgical Techniques for the Repair of Saddle Nose Deformity

The particular approach for the repair of a saddle nose deformity that one employs is influenced by the characteristics of the deformity to be addressed. For the correction of minimal deformities, a closed approach with septal and auricular might be employed. As the extent and severity of the deformity increases, the surgeon should progress along the path of more aggressive techniques including an open approach, and the use of larger volumes of material for augmentation.

Commonly used approaches include the endonasal approach, the cartilage delivery approach, and the open approach. It is the degree of complexity of the problem and surgeon’s comfort and skill level with each technique that will determine the chosen strategy. In the senior author’s opinion, if the amount of recontouring and augmentation is expected to be minimal, the closed approach is recommended. A closed approach allows the avoidance of some of the potential problems encountered in an open approach such as the disruption of the original structural support of the nose and tip, the external scar, and the increased operative time and postoperative tip edema. However, the open approach will provide more visible exposure if the corrective surgery requires the placement of a large graft or grafts, there is considerable asymmetry, or other challenging anatomic features.

Grafting and Augmentation Materials

Autografts

It is the opinion of the authors that the surgeon should use, when possible, autogenous materials. Autogenous materials have several advantages that include a low extrusion and infection rate and the ability to withstand transient bacterial contamination once revascularized. Autogenous materials also have the unique availability from the patient. The disadvantages are the obviously potential donor site morbidity and limitedness of the donor supply9.

Septal Cartilage

It is a common belief among many surgeons that the septum provides the optimal material for the fabrication of small to moderate sized grafts. It has favorable elastic characteristics that allow precise carving to correct subtle contour deficiencies; on the other hand, it can be used in several layers to correct more severe deficiencies. There are a variety of tools available to change the physical properties of these grafts, including morsilizers and crushers, to make changes in the cartilage for concealing subtle irregularities10.

In addition to providing volume for the correction of dorsal deficiencies, septal cartilage is frequently used in a variety of other applications. The septum, if available in adequate amounts, is generally considered the optimal choice for such applications as spreader grafts, columellar struts, and septal extension grafts.

One major limiting feature of its use, particularly in a patient who has previously undergone septal surgery or has saddling due to loss of the dorsal cartilaginous septum is its relatively limited supply.

Auricular Cartilage

These grafts are harvested from the anatomical locations of the concha cavum and concha symba and may have several advantages compared to septal cartilage. First, they are more abundant and generally available in patients with a history of previous septoplasty or non-iatrogenic causes of saddle deformity. Secondly, in a selective fashion the surgeon can employ the natural curvature and suppleness of conchal cartilage. As far as disadvantages, these cartilages are not as easily carved or morsalized as septal cartilage, and have a tendency to reveal their edges on the dorsum particularly in patients with thin skin and soft tissue envelope, unless they are meticulously tapered to the local contours11.

Costal Cartilage

Costal cartilage harvested from the transverse portions of the 6th through 8th ribs provides an abundance of grafting material that can be utilized to correct a sizable dorsal deficiency in cases of insufficient septal or auricular cartilage.

An obvious advantage of the use of rib cartilage for augmentation grafting is the sheer abundance of the material that is available, so that it can be carved into a variety of shapes and used to fill huge voids. Disadvantages include the potential donor site morbidity, including pneumothorax, hemothorax, and chest wall deformity. Patients usually have significant chest wall pain after the procedure. Another important disadvantage is the potential for “warping” or bending of the cartilage, which is a well-known complication, fairly unique to rib cartilage. The risk of this complication is thought to be minimized by “balanced carving”, and proper site selection12.

Diced Cartilage Grafts

Some authors have advocated the application of diced cartilage grafts, which can be placed as the primary graft, or also in combination with soft tissue graft (i.e. covered or wrapped in fascia). One obvious concern with this technique is resorption; however there are recent reports in literature with long term follow up showing success with this approach13.

Split Calvarial Bone Graft

There are some situations when bone grafts are preferable to cartilage grafts. It is the opinion of the authors that when a bone graft is desirable, the use of split calvarial has several advantages compared to other bony donor sites. It is readily accessible during nasal surgery, and is associated with minimal donor site morbidity and pain in comparison with some other bone graft donor sites such as the iliac crest. The posterior parietal area of the skull is our usual donor site as that area has a sufficiently thick diploic space and there is an ample area to obtain at sufficiently long specimen. Another advantage of these grafts is that they can be cantilevered at the nasion so that dorsal nasal support can be created in situations when there is a total loss of midline nasal support. As far as disadvantages, bone grafts are rigid and non-resilient, with a higher risk of fracture following future traumas. This is, therefore, prone to be problematic in the younger athletically active patient.

Soft Tissue – Perichondrium and Temporalis Fascia

The use of rigid or semi rigid augmentation material in rhinoplasty can occasionally lead to visible irregularities along the nasal dorsum, even with meticulous contouring techniques. This is particularly an issue with patients with thin skin. If this is anticipated in these situations, the soft tissue cover can be “thickened”, at least temporarily, while scar contraction is taking place with the use of soft tissue camouflaging grafts. The advantages of using perichondrium and temporalis fascia in these situations includes the absence of an immunologic response or infectious complication,as it is a concern with alloplasts, while the disadvantages include increased operative time and additional donor site morbidity.

Homografts

There continues to be use of homograft material in rhinoplasty. Irradiated cartilage has been safely used for structural grafting over the last several decades. There have been numerous articles describing its use and arguable persistence in the nose. There appears to be some persistence of augmentation, which is probably either due to the slow replacement of the implanted material by native fibrous tissue, or in some cases by the persistence of the material as a non-viable implant. It should be understood, however, that no viable chondrocytes are present in the grafted material and hence there is no revascularization of the graft, growth, or true integration with the native tissues. The use of homograft cartilage in the authors’ opinion should be limited to circumstances in which there are compelling reasons not to use native materials16,17.

On the other hand, another homograft tissue, processed dermis has been used in rhinoplasty. This material frequently serves well as a temporary soft tissue cushion that may help prevent scar contracture of the native skin over an irregular dorsum. The material appears to have considerable application as a single or double layer to serve to thicken the soft tissue envelope. The authors, however, would not recommend its use as a “filler” of defects, and again to be considered as a secondary choice to the native tissue, such as perichondrium or temporalis fascia. The long-term results of acellular dermal grafts have shown a high resorption rate and the need for overcorrection when the graft is used for augmentation18,19.

Alloplasts

Porous polyethylene, polytetrafluoroethylene, and silicone-based implants have been among the most widely used alloplastic materials in primary and revision rhinoplasty. In the authors’ opinion, in general, the use of alloplasts should be employed in situations when the use of autogenous tissues has been precluded. The nose frequently sustains minor and major trauma that leads to variably sized tears of the nasal lining causing at least a transient bacterial contamination. The mobile nature of the distal nose may further allow a breach of the lining or prevent effective vascular cover of semirigid alloplastic augmentation material. This may contribute to the higher risk of infection and extrusion associated with these materials.

Nevertheless, there are some situations where it becomes necessary to use alloplasts, and when encountered, some authors suggest the avoidance of the use of rigid and semirigid alloplasts in the mobile aspects of the nose14,15.

Graft Fixation

Grafts for augmentation can be placed in an “on-lay” fashion; usually describing the simple placement of well-contoured tapered grafts. For larger midline dorsal grafts, the authors frequently use a variety of methods to “fix” or suture the grafts in place using absorbable suture.

When grafts are placed during a smaller revision procedure, precise pockets can be dissected over the region in question allowing a form-fitting pocket to be developed to hold a graft in place. Finally, some surgeons use a variety of bioadhesives to hold the grafts in place.

Postoperative Analysis and Follow-up

For improvement of patient care and for the development of the surgeon in the craft of rhinoplasty, it is essential that patients be followed over time to assess the patient’s personal progress and to assess the effectiveness of the surgeon’s technique. We typically follow patients at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 4 months, and one year after the surgery date. Thereafter, the patient is followed at yearly intervals. Photodocumentation is the same as for preoperative analysis. It is through this longitudinal study that that surgeon can hone his craft and correct any deficiencies that are noticed over time. These intervals are shortened if there is any undesirable occurrence as recovery, healing, and scar contracture is taking place.

Illustrative Cases

The following clinical situations illustrate a spectrum of problems that may be encountered and the variety of techniques that may be employed in the approach to the patient with a saddle nose deformity.

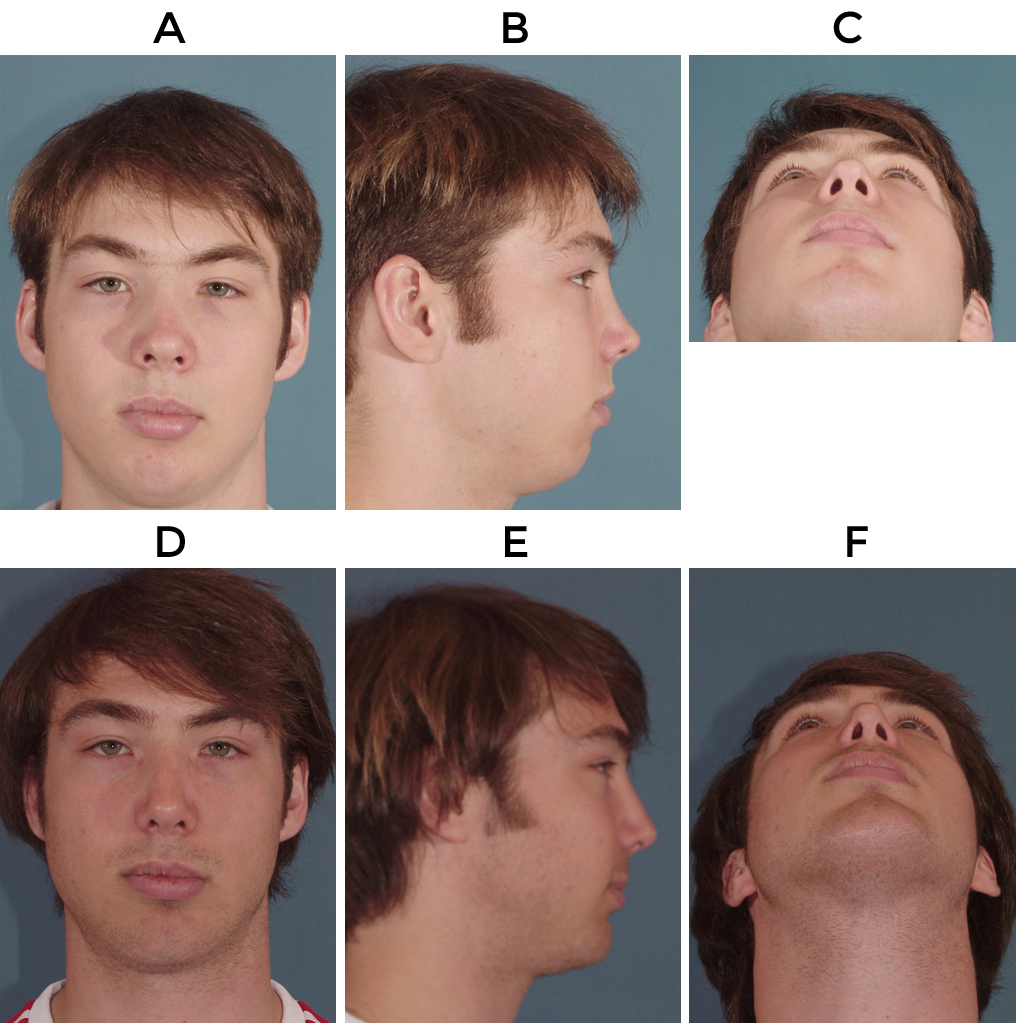

The patient depicted in figure 3 presented with posttraumatic bilateral middle vault collapse, severe septal deflection and a foreshortened septum. This was addressed via an open approach. The middle vault was managed with bilateral spreader grafts, followed by placement of auricular cartilage as a dorsal onlay graft and a blanket of auricular perichondrium as a camouflaging graft placed over dorsum and sidewall to minimize potential postop irregularities. The patient also had a septoplasty, lateral osteotomies, the placement of a columellar strut and a tip graft.

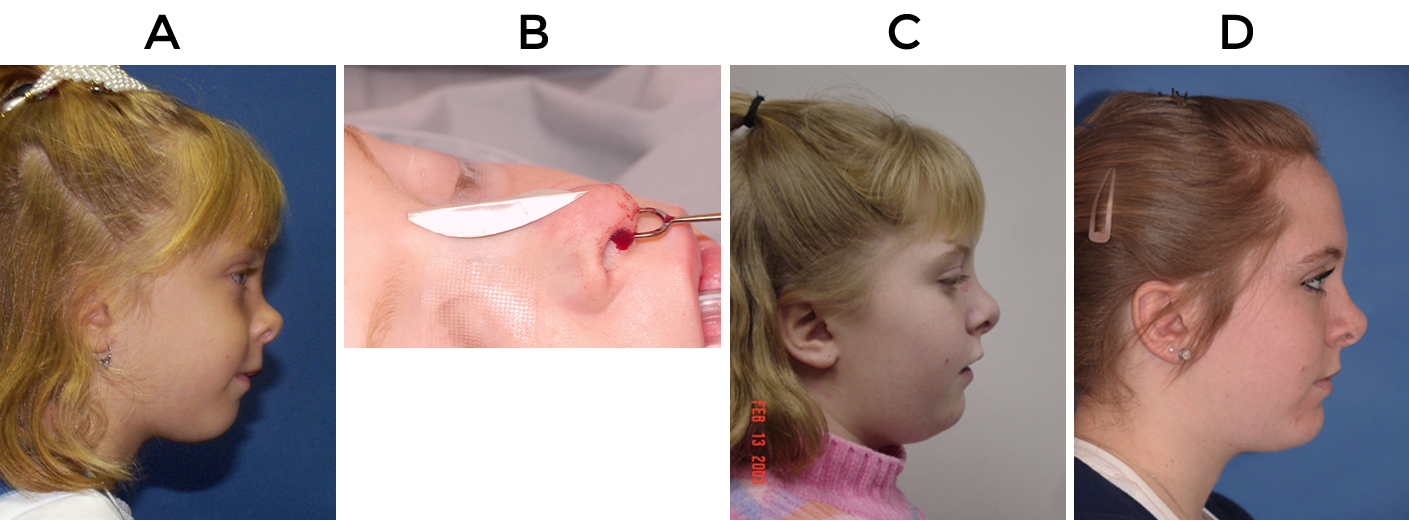

The patient depicted in figure 4 had a nasal dermoid cyst that was removed as a child and left her with dorsal insufficiency and arrest of normal dorsal growth. She was initially treated with a polytetraflouroethylene onlay implant to reduce her deformity until she was old enough to undergo definitive repair through autologous cartilage grafting. At age 17, she presented with displacement of her polytetraflouroethylene implant following a trauma and as such she underwent revision surgery via open approach and replacement of the implant using a double layered auricular cartilage graft as dorsal onlay to address her dorsal insufficiency. She also underwent bilateral auricular composite grafts to address her alar retraction, and placement of a columellar strut graft.

The patient in figure 5 is a patient who presented ten years years after a severe playground accident. Examination revealed saddling of the bony and cartilaginous dorsum with a foreshortened nose, contraction of the soft tissue envelope, severe septal deviation and left middle vault collapse.. Repair was performed via an open approach, with septoplasty, application of bilateral extended spreader grafts and an L-strut graft constructed from a costal cartilage donor site. She also underwent medial and lateral osteotomies, a septal extension graft.

Summary

The management of the patient with a saddle nose necessitates the surgeon to call upon his or her understanding of aesthetic principles and technical abilities. When presented with the situation, the surgeon has the privilege of intervening in a problem that may be of significant dissatisfaction for the patient. As illustrated above saddle nose deformity can present in a wide spectrum of severity and involving multiple structural components of the nose. In the patient with adequate midline nasal and tip support and presenting with only deficiencies of dorsal height and abnormal contour, relatively simple techniques might be employed. Such techniques may even involve a closed approach and an onlay graft over the nasal dorsum constructed using septal or auricular cartilage. As the problem becomes more complex with collapse of the middle vault due to weakness or deficiency of upper lateral cartilages or dorsal septum, then application of spreader grafts are of paramount importance in reconstituting both function and aesthetics in such noses. The more complex saddle noses, particularly in case of posttraumatic etiologies, present with a variety of other abnormalities including deflection or other deficiencies of septum, bony vault abnormalities, and the need for tip maneuvers in conjunction with middle vault issues.

The goal of this chapter was to give a practical overview and treatment strategy of saddle nose deformity, as one the more challenging problems faced by rhinoplastic surgeons. When successful in this endeavor, they have the gift of transforming the situation to one of great satisfaction and joy for the patient. So one continue to learn and teach; examine and study our results, so that one may rise to the occasion of performing our craft to the best of our abilities.

References

- Pribitkin EA, Ezzat WH.Classification and Treatment of the Saddle Nose Deformity. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42(3):437-461.

- Munro IR, Sinclair WJ, Rudd NL. Maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder’s syndrome). Plast Recontr Surg1979;63:657–663.

- Merkonidis C, Verma S, Salam MA. Saddle nose deformity in a patient with Crohn’s disease. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(7):573-576.

- Fedok FG, Preston TW. Managing the overresected dorsum. In: Becker DG, Park SS, editors. Revision rhinoplasty,.New York: Thieme; 2008:96-111.

- Tardy ME, Rhinoplasty tip ptosis: etiology and prevention. Laryngoscope 1973;83:923-929.

- Boahene DO, Orten SS, Hilger PA. Facial analysis of rhinoplasty patient, In Papel ID. (Ed). Facial Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery, 3rd ed. New York, Thieme. 2008:477-488.

- Kim DW, Toriumi DM. Nasal analysis for secondary rhinoplasty. Facial Plastic Surg Clin North Am 2003;11:399-419.

- Adamson PA, Doud Galli SK. Rhinoplasty approaches: current state of the art. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7(1):32-37.

- Adamson PA. Grafts in rhinoplasty, autogenous grafts are superior to alloplastics , Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126: 561-562.

- Calmak O, Buyuklu F. Crushed cartilage grafts for concealing irregularities in rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2007;9(5):352-357.

- Becker DG, Becker SS, Saad AA. Auricular cartilage in revision rhinoplasty, Facial Plastic Surg 2003;19(1):41-52.

- Sherris DA, Kern EB. The versatile autogenous rib graft in septorhinoplasty. Am J Rhinology 1998;12(3):221-227.

- Daniel RK. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery: current techniques and applications Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(6):1883-1891.

- Maas CS, Monhian N, Shah SB. Implants in Rhinoplasty, Facial Plast Surg. 1997;13(4):279-290.

- Romo T, Sonne J, Choe KS, Sclafani AP. Revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2003;19(4) 299-307.

- Clark JM, Cook TA, Immediate reconstruction of extruded alloplastic nasal implants with irradiated homograft costal cartilage. Laryngoscope. 2002; 112(6): 968-974.

- Kridel RW, Ashoori F, Liu ES, Hart CG. Long-term use and follow-up of irradiated homologous costal cartilage grafts in the nose. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(6):378-394.

- Tarhan E, Cakmak O, Ozdemir BH, Akdogan V, Suren D. Comparison of alloderm, fat, fascia, cartilage, and dermal grafts in rabbits. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2008;10(3):187-193.

- Sclafani AP, Romo T, Jacono AA, et al. Evaluation of acellular dermal graft (alloderm) sheet for soft tissue augmentation: a1-year follow-up of clinical observations and histological findings. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3(2):101-103.