Introduction

Rhinoplasty is one of the most commonly performed procedures by otorhinolaryngologists and facial plastic surgeons all over the world. Doctors should meet their patients’ expectations for optimal functional as well as aesthetic outcomes. However, when the question “aesthetics over nasal function?” arises, the answer is pretty simple, a surgeon should never compromise nasal function. Rhinoplasty is a highly personalized procedure. Despite its evolution since the time of Joseph, there is still no consensus on the best way to achieve reconstruction of the middle vault, dorsal augmentation as well as balanced tip support and shape correction. Many controversies remain and the majority of the currently published articles are mainly driven by reports of surgical techniques rather than patient outcomes.1 Revision rhinoplasty rates have been found to vary between 5% and 20%, with the main patient complaint being post-operative nasal airway obstruction, whereas the failure rate of septoplasty with or without inferior turbinate reduction is as high as 25% to 53%.2,3 These percentages underline the importance of nasal airway obstruction as an indication for primary or revision surgical intervention, as well as the fact that in a great number of cases nasal airway obstruction cannot be addressed by a simple procedure such as septoplasty and an escalation to functional septorhinoplasty is required.

In order to understand the principles of septorhinoplasty and the pathophysiology behind nasal airway obstruction one must master the anatomy of the middle vault. The paired upper lateral cartilages (ULCs) and the dorsal nasal septum compose the middle vault. Superiorly, the ULCs are fused with the nasal bones, underlapping the caudal margin of the bones, while medially they fuse with the cartilaginous nasal septum. Finally, the ULCs attach laterally to the pyriform aperture. In the scroll area, also known as recurvature area, we notice the attachment of the ULCs to the lower lateral cartilages (LLCs). Externally, the middle vault represents the transition from the narrow nasal bones superiorly to the wider nasal tip inferiorly, playing a critical role in shaping the dorsal and the brow-tip aesthetic lines, while endonasally it defines the internal nasal valve.4,5

The internal nasal valve (INV) was first described by Mink in the 1920s and represents the narrowest portion of the nasal airway.6 The INV is a three dimensional structure formed by the junction of the upper lateral cartilages and the nasal septum and is completed by the head of the inferior turbinate and the pyriform aperture. In Caucasians, the ideal INV angle is 10 to 15o, while for African Americans and Asians it tends to be wider. Caudally to the INV, one can identify the external nasal valve delineated by the septum, the medial and lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages and the premaxilla. The nasal airflow follows Poiseuille’s equation, thus narrowing the INV results in major decrease in nasal patency which translates to functional nasal airway obstruction. The INV collapse can be either static or dynamic, depending on whether the narrowing of the valve is present at rest or appears during inspiration. The static INV collapse is commonly the result of nasal trauma or iatrogenic, following nasal surgery (hump resection, septal cartilage resection, division of the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal septum). The stenosis can be the direct result of the change in the anatomic structures or can be due to scarring. Additional, static INV stenosis is present in patients with tension type nasal deformities, as a result of overprojection of the nasal septum. On the other hand, dynamic INV collapse can be attributed to inherent weakness of the lateral nasal wall, can present postoperatively after a rhinoplasty procedure with over-resection of the upper lateral cartilages and is also very common in age related nasal dysfunction.5 It is clearly understood that the preservation or the restoration of the INV function is pivotal in nasal surgery. What must also be underlined, is that narrowing the INV not only affects nasal breathing, but additionally interferes with the aesthetic part of the nose, as it disrupts the smooth brow-to-tip line.7 Thus, a number of techniques addressing this INV area have been described aiming to widen the cross-section area of the INV (such as spreader grafts, autospreader flaps) or to stabilize and strengthen the lateral nasal wall (alar batten grafts, stairstep grafts) or achieve a combination of both (splay and butterfly grafts). 8,9

In the dorsum, the deformities vary from subtle to dramatic as seen in saddle nose defects in patients with vasculitis. These deformities depending on their extent can be addressed with multiple approaches and techniques such as dorsally extended spreader grafts, onlay grafts, camouflage grafts and diced cartilage in fascia. The graft material can be either septal cartilage, conchal cartilage or costal cartilage, with the last being the best option in cases requiring strong structural support when septal cartilage is absent (revision rhinoplasty, vasculitis) or insufficient.10 On the other hand, the approaches to the nasal tip have evolved over the last decade mainly focusing on maintaining the native dome architecture and enhancing the tip stability. Based on this philosophy, the surgeon’s preference has shifted away from the pro forma use of cap, shield and collumelar strut grafts to caudal septum extension grafts and the floating collumelar strut.11,12

In the majority of cases, the septal cartilage can be used as the source for grafting material without necessitating an additional donor site incision. However, when septal cartilage is absent or insufficient in terms of quantity or quality, the need of extranasal grafting material arises. The commonly used sources include autologous auricular cartilage, costal cartilage , bone and composite grafts. Approximately, in 11% of primary rhinoplasties and in 25% of revision cases, an extranasal source of grafting material is required. The choice of the extranasal donor site depends on the unique benefits of each site, regarding intrinsic strength and warping potential in addition to risks associated with the donor site morbidity. The auricular cartilage is the most commonly used site (4 times more than costal cartilage in primary cases and twice as much in revision ones). Use of costal grafting is estimated from to 1.1% in primary cases to 7% in revision rhinoplasties and is mostly utilized in young patients, due to ossification of the costal cartilage at older age. On the other hand, conchal graft has been shown to have superior integrity and viability over septal cartilage in elderly and in terms of biochemical and histological changes it may be less susceptible to age related degradation compared with septal cartilage, so it seems like a good choice for older patients.13

In this chapter, we will analyze the most commonly used grafts in primary or revision functional septorhinoplasty, focusing on the indications and contradictions of each graft, the description of various techniques in harvesting and shaping of the graft and the placement options for each case. Illustrative pictures are provided as well as patient pre- and post- operative photos.

The spreader graft

The spreader graft was first described by Sheen in 1984 and nowadays is considered the gold standard in middle vault reconstruction.8 The traditional spreader grafts are rectangular grafts, 20-25mm in length, 3-4mm in height and 2-3mm in thickness that are placed submucosally between the ULCs and the nasal septum in order to widen the INV. They were at first used via closed approaches in primary rhinoplasties in patients with thin skin and weak ULCs as well as in cases with short nasal bones and narrow middle vault. When their use was extended to open approaches, the indications for them expanded including the restoration of the nasal dorsal aesthetic lines, the creation of a smooth transition at the key area, the reconstruction of the dorsal nasal roof, the restoration or preservation of the INV, especially after humpectomy, the buttressing of a corrected crooked nose and the splinting effect in cases of deviated dorsal segment of the nasal septum.5,14

In the endonasal operation, the spreader graft may be placed in one of two ways: it is either sutured- fixated under direct vision to the dorsal septal edge or it is placed in a submucosal pocket created between the ULCs and the nasal septum. With the submucosal placement, the perichondrium of both ULCs and the septum remain intact, providing increased tension and stability in INV restoration. When extended visualization is needed, the spreader grafts are easily placed via an open approach. They are easily stabilized with direct sutures usually using 5-0 non absorbable sutures in a horizontal mattress technique, with or without the use of a 30g needle for stabilization. The choice between placing the spreader grafts via an endonasal or an external rhinoplasty approach depends on the surgeon’s preference as well as the goals of the procedure.5 Spreader grafts are usually autologous grafts fabricated from septal, auricular or costal cartilage. Despite the fact that autologous graft material is ideal, a number of possible synthetic materials are listed in the literature, which can be used in revision cases where an adequate amount of cartilage is unavailable or distant graft harvest is avoided due to high donor site morbidity. Alternative materials that have been used as spreader grafts include hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, high-density porous polyethylene and polymer of polylactic and polyglycolic acid.5

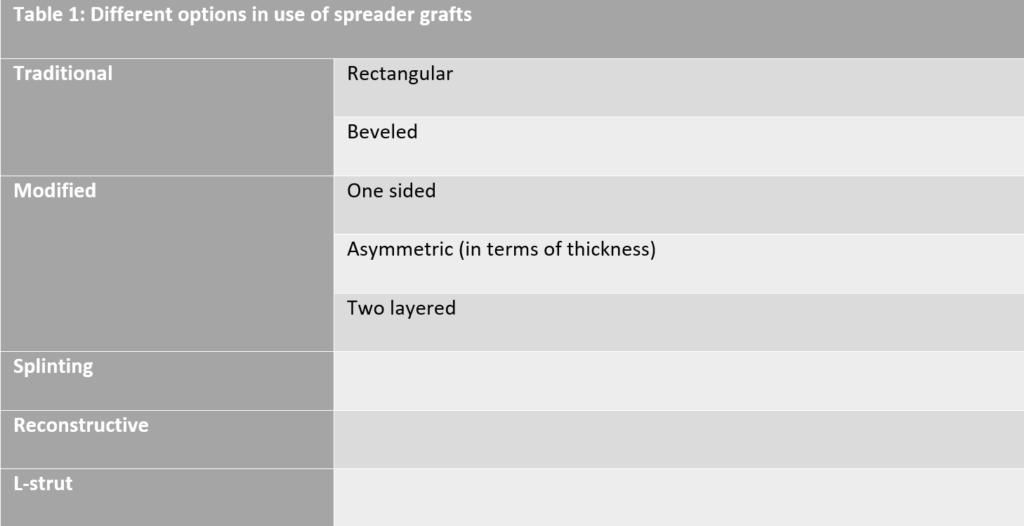

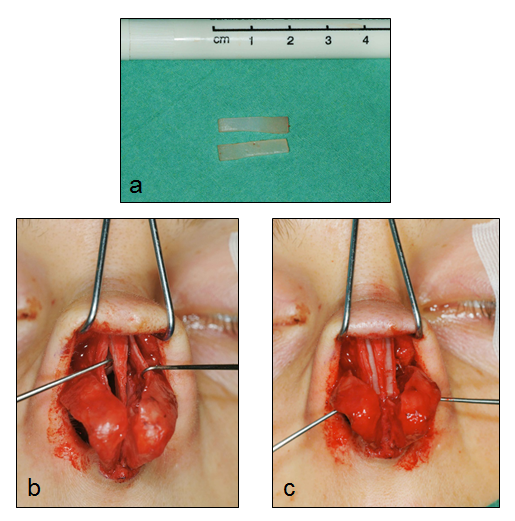

Over the last decades a number of options in the use of spreader grafts have been described. (see Table 1, Fig 1)14,15 In the traditional approach, the spreader grafts can be either rectangular, as described by Sheen, or beveled. In the original rectangular shape, the graft is placed in a way that its superior part is at the same height as the septal cartilage, the superior edge extends up to the caudal margin of the nasal bones, preventing an open roof deformity postoperatively, while the caudal edge of the graft is 2 to 3mm behind the anterior septal angle. (Fig 2) In the beveled form of the spreader grafts the cephalic and caudal edges of the grafts are curved in order to be placed under the nasal bones. In this way, a longer touching surface is achieved, ensuring better splinting as well as increased stability of the graft. Additionally, this type of placement prevents undesired graft pop-ups that are rarely seen postoperatively. In cases where the caudal edge of the graft is not beveled, a crowding effect at the INV area can be created and may result in nasal airway obstruction. In order to avoid this, it is suggested to remove the lower triangle of the caudal edge and additionally thin the graft at this side. In the modified approaches, the spreader grafts can be used either only in the one side of the septum in cases of crooked noses or can be used in both sides of the septum but the two grafts can be shaped asymmetrical in terms of thickness. The main goal in both approaches is to achieve the best possible symmetry throughout the entire axis of the nose. Finally, another modification of the spreader grafts has been described in cases where the graft thickness is not sufficient. In this cases, two layers of cartilage are sutured together in order to reach the desirable thickness. Apaydin F. notes that this is commonly the fact when auricular cartilage is used for spreader graft production. In severe crooked noses with high septal deviation the spreader grafts can be utilized for the splinting effect they provide, which is an alternative use. In these cases the grafts tend to be longer than usual and sometimes they are bony-cartilaginous instead of being solely cartilaginous as usual. Bilateral grafts tend to be used to “sandwich” a deformed septum, secured by multiple mattress sutures. Finally, the spreader grafts can be used in a reconstructive approach, solely or in combination with a columellar strut (as an “L-strut”) in cases where parts of the dorsal segment of the septum are deficient or need to be removed, combined or not with crooked caudal septal edge or a saddle nose deformity that needs to be corrected.15 To end the description of spreader grafts’ applications, one must remember their use in cases where a narrow nasal middle vault is combined with a wide and bulbous tip. In these cases, Boccieri et al propose a minimally invasive approach combining the use of spreader grafts with minimal cephalic trim of the lateral crura and the placement of intradomal sutures in order to improve brow- tip aesthetic lines without compromising the patency of the INV.16

Fig 1: Different types of spreader grafts (Apaydin et al, 2016)

Fig 1: Different types of spreader grafts (Apaydin et al, 2016)

The spreader flaps

Spreader flaps or autospreader grafts are designed from the ULCs and have been presented as a viable alternative to the traditional spreader grafts. They were first described by Oneal and Berkowitz in 1990s, but the idea seems to be a bit older since Fomon et al presented the buckled ULCs as a treatment approach for collapsed ala in 1950s.15,17 This technique utilizes the height of the ULCs that remains after dorsal hump reduction. The ULCs are dissected from the nasal septum and after the humpectomy, they are folded over on themselves and then are stabilized to the remaining dorsal septum via mattress non absorbable sutures leading this way to the reconstruction of the middle vault and the restoration and widening of the INV. (Fig 3) This interesting technique has received increased attention over the years, with many publications in the literature examining its effectiveness and its limitations. Over the years, a number of modifications have been described and the indications for their use have expanded, including the presence of long and thin nasal dorsum, short nasal bones, weak middle vault composed by thin ULCs and/ or nasal bones, thin nasal skin or a preoperative positive Cottle maneuver. Despite the attractive and promiscuous role of speader flaps, in the only available randomized trial, up to now, Saedi et al were unable to confirm their benefit over placebo in the preservation of the INV angle following hump removal.18 However, the effect of spreader flaps needs further evaluation. Recently, the application of the spreader flaps without dorsal hump reduction has been proven effective in correcting the INV collapse compared to the result of spreader grafts application.19

Fig 3: Traditional autospreader flaps. ULCs turned inwards and sutured to the nasal septum.

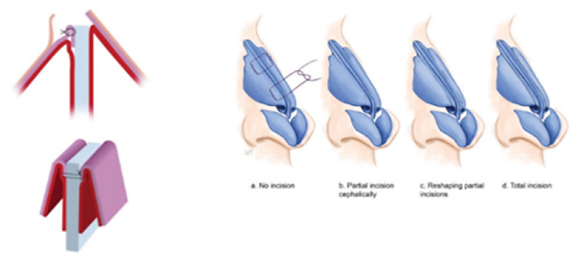

Types of incisions made to the ULCs (Apaydin et al, 2016, Wurm & Kovacevic, 2013)

The spreader flap technique offers many advantages including the maximal use of the local tissue, the simplicity of the technique without the need of harvesting additional cartilage and the efficacy in nasal patency preservation. On the other hand, one must underline the inadequacy of spreader flaps when used alone in cases of severe septal/ nasal asymmetry, as well as the difficulty in utilizing spreader flaps via closed approaches as general limitations.20 Wurm J. and Kovacevic M. have described four types of spreader flaps: basic, flaring, support and interrupted type. In the cases of basic and flaring spreader flaps the authors have underlined a tendency towards a slightly wide middle nasal vault, in some cases even requiring revision surgery, whereas the other two types (support and interrupted spreader flaps) lead to an appropriate middle nasal vault width and an aesthetically more pleasing result.21 The same authors have evaluated the indication for spreader flaps in primary rhinoplasty patients with hump noses, hump/tension noses and moderately hooked or crooked noses. They underline the fact that careful patient selection is the keystone for success in the use of spreader flaps as a reliable alternative to spreader grafts and in the majority of cases no additional cartilage grafting was required.22 Sowder J.C. et al concluded that the spreader flap is equivalent to the spreader graft in improving nasal airway patency due to INV collapse without having humpectomy as a prerequisite.19 A surgeon must keep in mind the fact that the final result of the surgery is susceptible to a number of factors including the memory of cartilage tissue, that must be contrasted during the surgical steps, the scarring, the reabsorption of the cartilaginous grafts and the skin retraction. Taking these into consideration, it becomes clear the need of combining both spreader grafts and spreader flaps in difficult cases with severe septal deviation in order to achieve a proper and stable long term result.20

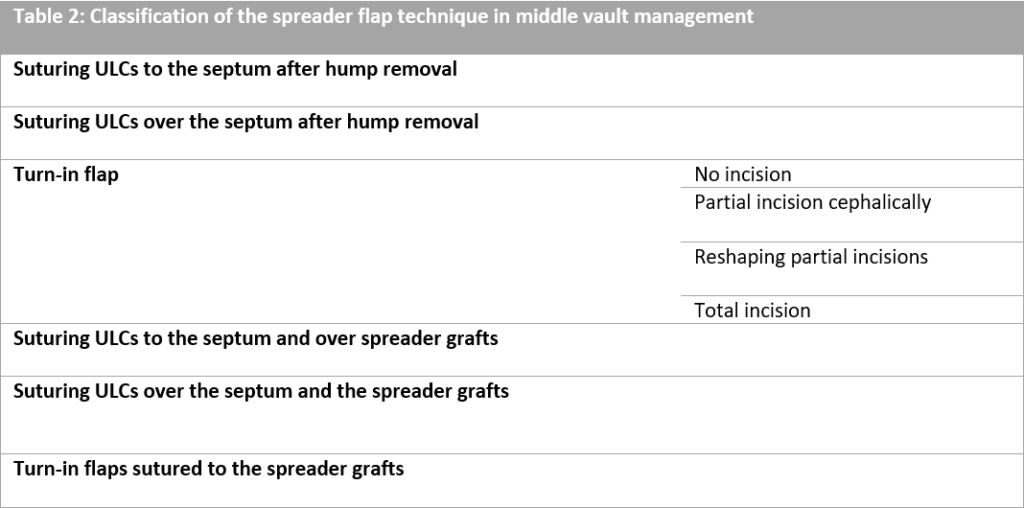

A classification of the spreader flap use in the reconstruction of the middle vault is listed in Table 2.14,15 When the ULCs are separated from the nasal septum there are three basic options: to use turn-in flaps, to suture the ULCs to or over the septum with minimum hump reduction or to combine the use of spreader flaps with spreader grafts. (Fig 3) The turn-in flaps represent the classical design for spreader flaps. After hump removal, the separated ULCs from the nasal septum are evaluated in terms of stability and elasticity. With the use of forceps, the surgeon turns the dorsal part of the ULCs inwards examining the effect of this maneuver to the INV width. The mucoperichondrium under the ULCs should be restorted as it helps stabilizing the ULCs and adds to the widening of the INV angle since a double layer of mucoperichondrium is formed between the turned-in flaps. In the first years of the spreader flap use, there was a trend in removing the mucoperichondrium of the ULCs in order to avoid cyst formation inside the flap, but this decolonization of the ULCs resulted in reduced stability of the flap as well as in inadequate INV width, especially in cases with thin, long ULCs. Depending on the rigidity of the ULCs, the surgeon can simply turn them inwards and stabilize them to the nasal septum via two mattress sutures placed cephalically and caudally, whereas in cases with stiff and strong ULCs in order to retain the spring effect of the turn-in flap, incisions need to be made. The incision can be either limited to the cephalic part of the flaps and can be reshaped or not during surgery, depending on the forces noticed to the sutures placed or they can extend to the whole length of the flap.15 (Fig 4, 5)

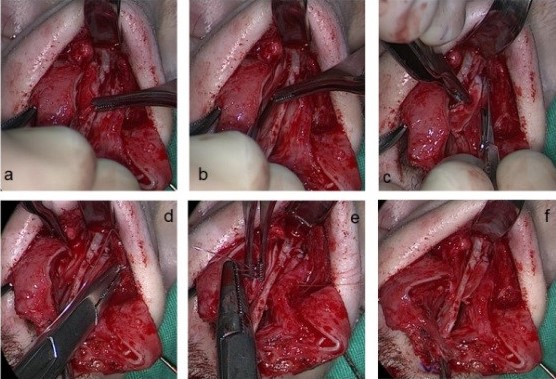

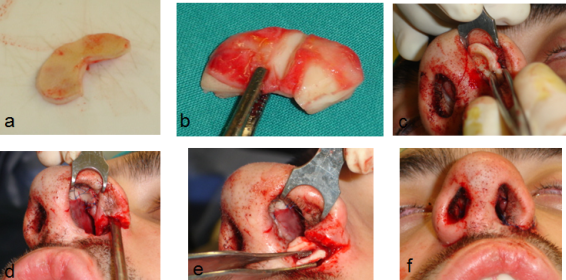

Fig 4: Intraoperative photos of the separation of the ULCs from the nasal septum (a),

the incision of the ULCs and turning them inwards (b, c), their suturing to the nasal septum (d,e,f)

The second approach with the suturing of the ULCs to or over the septum is very well utilized in the endonasal septorhinoplasty and can be effective in cases with limited hump. When the hump is not extending to the lower half of the middle vault and there is no need to narrow the cephalic half, the surgeon can suture the ULCs to the nasal septum. However, in cases of a limited bony hump with no need of narrowing the bony vault, the surgeon can rasp the hump and without disrupting the INV in the first place, he can suture the ULCs over the nasal septum. In this approach, the nasal septum and the intact mucoperichondrium under the ULCs work as a fulcrum stabilizing the INV in the desired shape.15

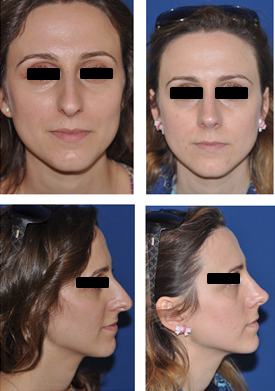

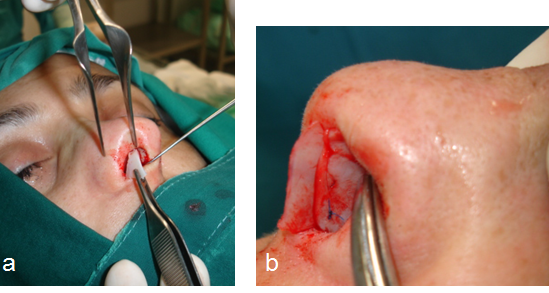

Fig 5: Middle vault reconstruction with autospreader flaps

(pre- operative photos on the left, post- operative photos on the right)

In cases with significant septal or nasal tip deviation as well as in cases characterized by weak tip support, the use of spreader flaps should be combined with the traditional spreader grafts in order to reach a stable, satisfying long term result.19 In crooked noses, the ULCs can be sutured to the septum and over the spreader grafts, providing splinting to the nasal septum and resulting in adequate INV angle due to the presence of spreader grafts underneath, that also prevents the possibility of ULCs’ inferomedial collapse. In some cases where the width of the middle third is adequate, suturing the ULCs over the nasal septum and the spreader grafts is a viable surgical choice resulting in an even straighter and smoother profile on the middle third. On the other hand in very narrow noses, the surgeon can utilize the combination of turn-in flaps and spreader grafts by suturing the flaps to the grafts to the septum providing by this technique the maximum widening to the middle third of the nose.15

The butterfly graft

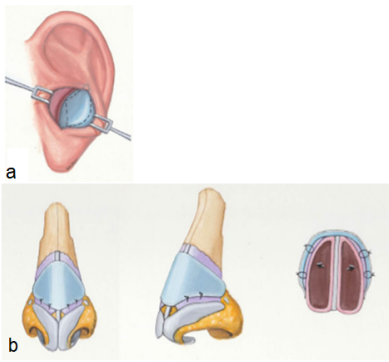

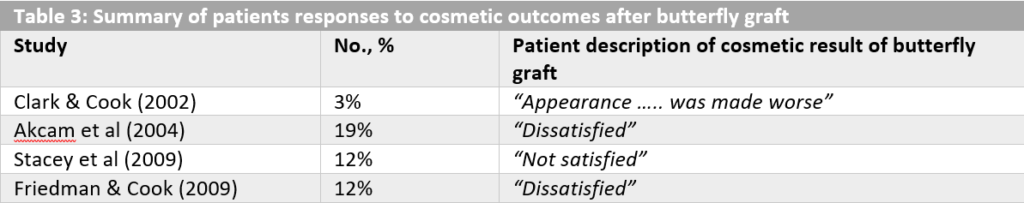

The butterfly graft is a term used to describe an auricular cartilage graft that is utilized to restore the INV angle aiming in restoration of nasal airway patency. The graft was originally described by Claus Walter in 1977 in Germany, but became popular after the publication of Clark and Cook in 2002 which was analyzing the effect of the butterfly graft in revision rhinoplasty.23 As originally described, the butterfly graft is a triangular cartilage graft that is harvested from the ascending portion of the conchal bowl, utilizing its smooth curvature, and is, afterwards, placed into a sub-superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) pocket through a bilateral intercartilaginous incision. The cartilage lays over the caudal part of the ULCs and slightly under the cephalic margin of the LLCs. Moreover, this technique can be modified with the use of a composite graft that is harvested from the auricle in cases where scarring in the INV area is the main reason for impaired nasal patency. Although the primary description of the butterfly graft was referring to an endonasal approach, with or without septoplasty, an open approach can also be utilized. The presence of the butterfly graft has a stenting effect on the ULCs and the LLCs, widening the INV angle and strengthening the lateral nasal wall, thus improving nasal breathing.24,25 (Fig 6) In the original report, by Clark and Cook, all patients that underwent revision rhinoplasty with the use of a butterfly graft reported improvement in nasal breathing and in 97% complete resolution of their symptoms was achieved.23 Despite the fact that similar success rates have been reported by other surgeons as well, the butterfly graft still has not been used as widely as the spreader grafts or the autospreader flaps. The need of a donor site for the cartilage graft in combination with the occasional widening of the supratip area and the fullness in the middle third of the nose following the positioning of the graft are the main reasons the surgeons are reluctant to widely use this graft. In Table 3, the percentages of the patients that reported dissatisfaction of their cosmetic result after butterfly graft appliance in primary or revision rhinoplasty are outlined. With the patient dissatisfaction over the aesthetic result ranging from 3% to 19% despite careful patient selection, the need of certain modifications of the butterfly graft was highlighted.24

Fig 6: a) Harvesting of the graft (auricular cartilage), b) positioning of the graft results in

widening the INV area (Chaiet S.R., Marcus B.C. 2014, Loyo M. et al 2016)

Over the last years, a number of reports in the literature presented modifications of the butterfly graft technique that made it more appealing in primary and revision rhinoplasty. The original size of the graft was 2,0 to 2,5 cm in length (horizontal) and 1 to 1,5 cm in width (cephalocaudal). The experts of this approach suggest extensive carving of the cartilaginous graft with scalloping of the edges, based on the individual characteristics of each patient, that result in a customized graft in terms of size as well as shape, with a trend towards smaller sizes (an average of 1,8 cm in length and 0,9 cm in width).2 (Fig 7)

Fig 7: Modifications of the butterfly graft technique.

Extensive carving of the cartilaginous graft with scalloping the edges leads to

reduced nasal tip volume post-operatively. (Chaiet S.R., Marcus B.C. 2014, Loyo M. et al 2016)

However, Loyo M. at al reported that the major feature that influences the aesthetic result is the width and not the length of the butterfly graft, describing an increased length and decreased width butterfly graft, that results in improved nasal airway patency combined with a good aesthetic result.25 In order to avoid a supratip fullness or a polly-beak deformity, the ULCs are released from the dorsal septum and a depression within it is created, for the graft to sit at. Additionally, the lateral wings of the graft are common sites detectable postoperatively setting the base for a patient complaint. The reduction of the lateral graft wings is preferably performed in situ after careful assessment of their prominence. Last but not least in the proposed modifications, the surgeons are advised to incorporate the perichondrium of the auricular cartilage to the graft, as it provides better stability of the graft and parts of it can be utilized as camouflage at the graft borders.2

Despite the aesthetic concerns regarding the fullness in the middle third of the nose or the widening of the supratip area, there are indications where the use of buttergly graft leads to a better aesthetic result compared with other types of grafting. In patients with saddle nose deformity from trauma, prior overly aggressive septoplasty combined or not with reduction rhinoplasty, this increased fullness in the middle third creates a significant aesthetic improvement in dorsal nasal aesthetics.2

There are certain limitations in the use of butterfly graft.7,24 Patient’s skin thickness is a parameter that must be evaluated. Thin skin cannot adequately hide the underneath presence of the graft, thus being a limitation in the butterfly graft application. Moreover, calcified and inelastic conchal cartilage, mostly seen in elderly, is a contra-indication as it fails to provide the flexibility that is essential for nasal airway patency. Finally, patients with pinced dorsal nasal shape suffering from INV dysfunction have proven to be bad candidates for this type of graft, as it can alter significantly and in an undesirable way the dorsal nasal aesthetics.26

The authors’ opinion is that the butterfly graft technique is an excellent choice in cases of revision rhinoplasty where the septal cartilage is inadequate to provide spreader grafts or even completely absent. Additionally, the utilization of a composite butterfly graft in revision cases with scarring in the INV area results in the restoration of the nasal patency. However, despite its modifications the butterfly graft doesn’t seem to be an appealing choice in cases of primary rhinoplasty. (Fig 8)

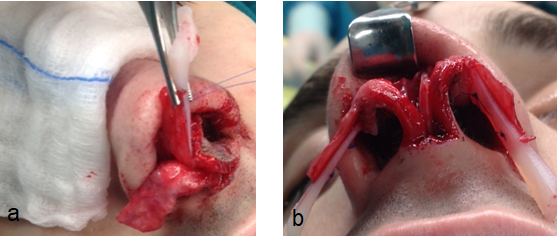

Fig 8: Butterfly composite graft and alar strut in patient with cleft nose: Auricular cartilage harvested (a), carved (b), placed

and sutured via a closed approach (intercartilaginous incision) (c), cartilaginous support placed in the alar base on the left side (d & e)

resulting in a similar level of the alar base in both sides (f).

Tip grafts: the columellar strut- the caudal septal extension graft- the alar strut and alar batten graft

A septorhinoplasty procedure in order to be successful should result not only in a well-constructed nasal middle vault but additionally to a well-defined and properly projected nasal tip. Nasal tip plays critical role to the aesthetics of the nose but moreover, it influences the nasal airflow as it participates to the formation of the nasolabial angle. Its framework includes the alar cartilages that with their medial and lateral crura form a tripod. Patients with deviation of the caudal septum and weak tip support due to short nasal septum, have acute nasolabial angles that result in reduced nasal airflow, suffering nasal obstruction. 27 Nasal tip underprojection combined with narrow nasolabial angle is a common nasal deformity characterized by long nose appearance, known as “drooping nose”. Surgical control of the nasal tip has proven to be difficult. The key point is to retain the ability of the alar cartilages to provide a “spring effect” that secures the nasal valve patency. Over the years, various surgical techniques aiming to reshape and reposition the nasal tip have been described, many of which include the use of grafts.28 Each technique is evaluated in terms of postoperative tip rotation, sensitivity and rigidity of the nasal tip as well as the aesthetic outcome.29 The majority of surgeons use a variety of methods, solely or combined in order to obtain the desired correction of the nasal tip. The tip projection, the acuity of the nasolabial angle, the prominence of the columellar and the degree of deviation for both columellar and caudal septum are the parametres that need to be taken into account when determining the surgical approach.30 In this chapter the most commonly used grafts in tip surgery will be analyzed: the columellar strut, the caudal septal extension graft, the alar strut and alar batten grafts. All four grafts can be utilized in closed, endonasal approaches as well as in external approaches via a trans-columellar incision.

The columellar strut was first described by Eithen in 1932 in “Kosmetishe operationen”. Eithen presented a graft positioned between the media crura in order to provide support to tip projection in patients with bulbous tip or fatty skin noses, but it was Baum, the one that set the indication of columellar strut for fatty skin noses and bulbous tip in closed approaches, proving that the positioning of the graft results in simultaneous upward projection of the lateral crura, maintaining long-term tip projection postoperatively.31,32 On the other hand, in open rhinoplasty the trans-columellar incision itself, disrupts the tip support mechanism necessitating the use of columellar strut in a preventative manner in order to avoid de-projection of the tip postoperatively. The presence of the columellar strut opposites the forces of the depressor septi nasi muscle as well as the skin contraction due to scarring. The columellar strut is usually harvested by autologous septal cartilage, whereas in cases of insufficiency costal or auricular cartilage can be utilized.33 Moreover, in cases where the procedure includes hump resection, one can use the resected hump after appropriate processing as a columellar strut.34 The cartilage is cut in a rectangular shape, the dimensions of which is completely personalized based on each patient’s unique anatomy. This step, in clinical practice, is based on availability of cartilaginous graft in combination with the surgeon’s expertise. Afterwards, the strut is placed between the medial crura along the caudal end of the septum reaching the nasal spine. In this position, it can be stabilized by many ways. First, in 1944, Danley proposed a mattres suture, whereas in the years that followed many new approaches have been described such as the “dual-knot” fixation of the strut to the anterior nasal spine or the use of trans-septal columellar stabilizing suture.33,35,36,37 In a finite element analysis of the columellar strut, Gandy JR. et al proved that sutures should be placed along the entire graft or at the most- anterior portions to the alar cartilages, as in this approach the optimal tip support is achieved.33 The caudal septal extension graft is a cartilaginous graft placed in a way that overlaps the caudal nasal septum margin and is sutured between the medial crura of the alar cartilages. It was first described by Byrd et al in 1997 who reported a graft fixation to the caudal or dorsal septum achieving controlled increase in the nasal length and ensuring tip projection, rotation and shape.38 This graft is utilized in cases where the columellar strut used alone would be insufficient i.e. in the presence of deviation of the caudal septum combined with short nasal septum. In such cases the caudal septal extension graft can be used endonasally supporting nasal tip and straightening the septal deviation.39 This graft is commonly utilized in Asian primary rhinoplasty due to the anatomy of the Asian nose (weak and small alar and septal cartilages with acceptable bony dorsum), as well as in revision septorhinoplasties of the Caucasian population due to postoperative under- projection of the nasal tip and over-resection of the nasal cartilaginous framework.27,40,41,42 Moreover, the caudal septal extension graft can be used in open approaches solely or in combination with tongue-in-roof technique. Conventionally, the graft is secured permanent sutures and sometimes it is additionally fixated to the anterior nasal spine. However, a new publication questions the necessity of permanent sutures and/ or fixation to the nasal spine, describing similar outcomes with the use of absorbable sutures used for side-to-side fixation of the graft.43 (Fig 9)

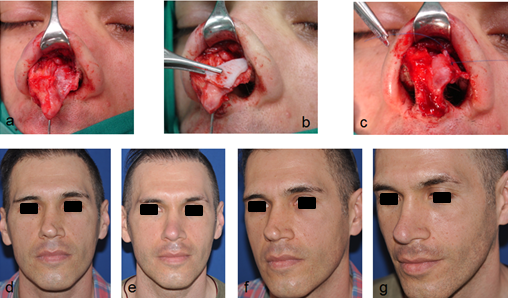

Fig 9: Caudal extension graft: placement of the graft via an endonasal approach (a-b)

The alar strut and alar batten grafts are rectangular or curved cartilages that are placed to the side of the maximum lateral nasal wall collapse, over or under the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages enlarging and stabilizing the internal and the external nasal valve.44 The alar strut grafts are used in order to enlarge the existing lower lateral cartilage, whereas the batten grafts are the optimal option in reconstruction of the lateral nasal wall in cases of hypoplasia or total absence of the lower lateral cartilage. (Fig 10, 11)

Fig 10: Extended alar strut placed via an open approach (a,b)

Fig 11: Placement of extended alar strut for reconstruction of the nasal tip in a revision rhinoplasty.

Pre-operative photos a, c, e, g, Post-operative photos b, d, f, h

All alar batten grafts are typically produced by septal cartilage, but auricular cartilage can be also utilized with its main advantage being its natural curvature.45 The grafts can be placed via a limited endonasal incision into a precise pocket or via an open approach, where typically sutures are used to stabilize the graft. The convex portion of the graft is oriented laterally to allow maximal lateralization of the collapsed portion of the lateral nasal wall. Moreover, the placement of the grafts caudally to the lateral crura, extending typically from their lower one third to the pyriform aperture leads to a significant increase in the size of the aperture at the internal and the external nasal valve. The main disadvantage of this technique is a post-operative fullness in the supra-alar region, which in the long term subsides with overall improvement of the aesthetic result.46 (Fig 12) The technique is simple and its efficacy has been proven by a number of studies in the literature.44,45,46,47,48,49 However, there are certain limitations in their application such as intanasal scarring involving the nasal valve area, loss of vestibular skin in trauma or revision cases, as well as excessive narrowing of the pyriform aperture. In these cases, the application of the alar batten grafts can be either impossible or ineffective.44,46

Fig 12: Alar batten graft: (a) asymmetry of the lower lateral cartilages after primary rhinoplasty, (b) rectangular curved graft

placed to the side of the maximum lateral nasal wall collapse, on the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages via an open approach,

(c) fixated with a non-absorbable suture, (d & f) pre-operative photos, (e & g) post-operative photos.

References

- Spielmann P.M., White P.S., Hussain S.S. (2009) Surgical techniques for the treatment of nasal valve collapse: a systematic review. Laryngoscope 119, 1281-1290

- Howard B.E., Clark J.M. (2019) Evolution of the butterfly graft technique: 15- year review of 500 cases with expanding indications. Laryngoscope 00:1-10

- Goudakos J.K., Daskalakis D., Patel K. (2017) Revision rhinoplasty: Retrospective chart review analysis of deformities and surgical maneuvers in patients with nasal airway obstruction- five years of experience. Facial Plast Surg 33:334-338

- Stucker F.J., De Souza C., Kenyon G.S., Lian T.S., Draf W., Schick B. (2009) Rhinology and Facial Plastic Surgery, Springer

- Kim L., Papel I.D., (2016) Spreader grafts in functional rhinoplasty .Facial Plast Surg 32:29-35

- Mink J.P. (1963) Le nez comme voie respiratorie. Presse Otolaryngol (Belg) 21: 481-496

- Friedman O., Cook T.A. (2009) Conchal cartilage butterfly graft in primary functional rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 119: 255-262

- Goudakos J.K., Fishman J.M., Patel K. (2016) A systematic review of the surgical techniques for the treatment of the internal nasal valve collapse: where do we stand? Clin. Otolaryngol. 2016, 00: 000-000

- Gassner HG, Maneschi P, Haubner F. (2014) The stairstep graft: an alternative technique in nasal valve surgery. JAMA Facial Plast Surg Nov- Dec 16(6): 440-3

- Wong B.J.F., Friedman O., Hamilton III G.S. (2018) Grafting techniques in primary and revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 26:205-223

- Toriumi D.M. (2006) New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast Surg 8:3-156

- Hamilton G. (2015) Form and function of the nasal tip: reorienting and reshaping the lateral crus. Facial Plast Surg 32:49-58

- Lee L.N., Quatela O., Bhattacharyya N. (2018) The epidemiology of autologous tissue grafting in primary and revision rhinoplasty. The Laryngoscope 00:1-15

- Gassner HG, Friedman O, Sherris DA, Kem EB (2006) An alternative method of middle vault reconstruction. Arch Facial Plast Surg Nov- Dec; 8(6):432-5

- Apaydin F. (2016) Rebuilding the middle vault in rhinoplasty: a new classification of spreader flaps/ grafts. Facial Plast Surg 32:638-645

- Boccieri A., Marco C., Pascali M., (2005) The use of spreader grafts in primary rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg 55:127-131

- Oneal R.M., Berkowitz R.L. (1998) Upper lateral cartilage spreader flaps in rhinoplasty. Aesthet. Surg. J. 18:370-371

- Saedi B., Amaly A., Gharavis V. et al (2014) Spreader flaps do not change early functional outcomes in reduction rhinoplasty: a randomized control trial. Am J Rhinol Allergy 28:70-74

- Sowder J.C., Thomas A.J., Gonzalez C.D., Limaye N.S. (2017) Use of spreader flaps without dorsal hump reduction and the effect on nasal function. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 19:287-292

- Barone M., Cogliandro A., Salzillo R. et al (2019) Role of spreader flaps in rhinoplasty: Analysis of patients undergoing correction for severe septal deviation with long-term follow-up. Aesth Plast Surg 43:1006-1013

- Wurm J., Kovacevic M. (2013) A new classification of spreader flap techniques. Facial Plast Surg 29:506-14

- Kovacevic M., Wurm J. (2015) Spreader flaps for middle vault contour and stabilization. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 23:1-9

- Clark J.M., Cook T.A., (2002) The “butterfly” graft in functional secondary rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope 112 (11):1917-1925

- Chaiet S.R., Marcus B.C. (2014) Nasal tip volume analysis after butterfly graft. Ann Plast Surg 72(4):490

- Loyo M., Gerecci D., Mace J.C. (2016) Modifications to the butterfly graft used to treat nasal obstruction and assessment of visibility. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 18(6):436-440

- Stacey D.H., Cook T.A., Marcus B.C. (2009) Correction of the internal valve stenosis: a single surgeon comparison of butterfly versus traditional spreader grafts. Ann Plast Surg 63:280

- Gursoy K et al (2019) Biomechanical analysis of a modified suture technique for septal extension grafts: Transloop suture. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 72(11):1825-1831

- Demir UL (2018) Comparison of tongue-in-groove and columellar strut on rotation and projection in droopy nasal tip: contribution of a cap graft. J Craniofac Surg 29(3):558-561

- Karaiskakis P et al (2016) Reconstruction of nasal tip support in primary, open approach septorhinoplasty: a retrospective analysis between the tongue-in-groove technique and the columellar strut. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(9): 2555-60

- Khan N.A., Rehman A., Yadav R. (2016) Uses of various grafting techniques in external approach rhinoplasty: an overview. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 68(3): 322-328

- Eithen E. (1932) Kosmetische operationen. Springer. Wien

- Baum SJ. (1977) Nasal projection. Arch Otolaryngol 103:262-267

- Gandy J.R. et al (2016) Quantifying optimal columellar strut dimensions for nasal tip stabilization after rhinoplasty via finite element analysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 18(3):194-200

- Giacomini P.G. et al (2018) The hump columellar strut: a reliable technique for correction of nasal tip underprojection. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica 38:45-50

- Daley J. (1944) Retaining a correct septolabial angle in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 39:348-352

- Ozkan C. (2019) “Dual-knot fixation” technique for better stabilization of the extended columellar strut graft with the anterior nasal spine. Aesthetic Plast Surg 43(1):202-205

- Jeong JY. Et al (2018) A new method for stabilizing the columellar strut used in rhinoplasty: the trans-septal columellar stabilizing suture. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 76(1):165-168

- Byrd HS et al (1997) Septal extension grafts: a method of controlling tip projection shape. Plast Reconstr Surg 100:999-1010

- Karadavut Y. et al (2017) Effectiveness of caudal septal extension graft application in endonasal septoplasty. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 83(1):59-65

- Chen YY, Kim SA, Jang YJ (2019) Centering a deviated nose by caudal septal extension graft and unilaterally extended spreader grafts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Dec 11:3489419894617 (Epub ahead of print)

- Ahn TH et al (2019) New technique in nasal tip plasty: sandwich technique using cartilage and septal bone complex. Ear Nose Throat J Oct 13: 145561319881570 (Epub ahead of print)

- Hwang NH, Dhong ES (2018) Septal extension graft in Asian rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 26(3):331-341

- Benavides G, Villate P, Malaver C. (2019) Caudal septal extension graft sutured with absorbable material and not fixed to the nasal spine region compared with the conventional fixation method: a retrospective study. Aesthetic Plast Surg 43(3):759-767

- Chua DY, Park SS (2014) Alar batten grafts. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 16(5):377-8

- Becker DG, Becker SS (2003) Treatment of nasal obstruction from nasal valve collapse with alar batten grafts. J Long Term Eff Med Implants 13(3):259-269

- Toriumi DM et al (1997) Use of alar batten grafts for correction of nasal valve collapse. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123(8):802-8

- Millman B (2002) Alar batten grafting for management of the collapsed nasal valve. Laryngoscope 112(3):574-9

- Sufyan AS et al (2013) The effects of alar batten grafts on nasal airway obstruction and nasal steroid use in patients with nasal valve collapse and nasal allergic symptoms: a prospective study. 15(3):182-6

- Cervelli V et al (2009) Alar batten cartilage graft: treatment of internal and external nasal valve collapse. Aesthetic Plast Surg 33(4):625-34