Introduction

Premaxillary and perialar retrusion is a common finding in Asians and Africans1,2. Being in the immediate vicinity of the nose, these anatomic features directly affect the cosmetic outcome of rhinoplasty and thus warrant the attention of the rhinoplasty surgeon. We conceptualize this anatomic anomaly as a spectrum from mild premaxillary and perialar retrusion to midface hypoplasia, and at the far end of the spectrum is a congenital malformation known as nasomaxillary dysplasia or Binder’s syndrome3-5. This condition can also occur in patients with “adenoid facies”, in which nasal/nasopharyngeal obstruction and the consequent chronic mouth breathing from young leads to poor midfacial development6,7. While milder forms of premaxillary and perialar retrusion are common, they are often under-recognized and under-managed. Correction of the paranasal deficits can make a significant difference in the aesthetic outcome in rhinoplasty and we would like to share our technique in the management of this condition, in the context of rhinoplasty.

Anatomy

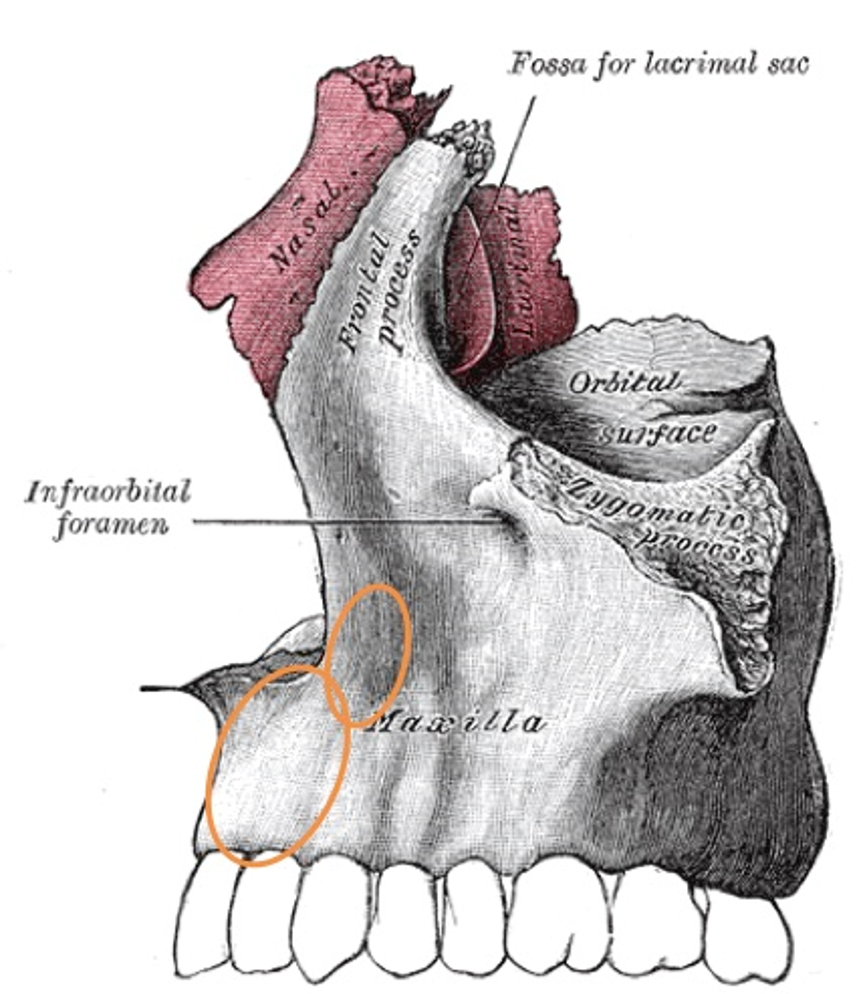

The premaxilla or alveolar process of maxilla lies anterior to the incisive foramen and comprises of the maxillary crest, the anterior nasal spine and upper incisors. The perialar region is formed by the inferolateral ridges of the pyriform aperture and part of the frontal process of the maxilla.

Anatomically, the midface comprises of the nose, maxilla, palate and upper lip (Figure 1). The embryological origin of the midface, upper face and mandible are distinct8. The lateral aspect of the nose is formed from the lateral nasal processes and the central part of the nose and the philtrum are formed from the medial nasal process. The maxilla is formed from the paired medial and lateral maxillary processes. The lateral nasal process fuses with the paired medial maxillary process at the nasofacial groove. As these embryonic processes are in close approximation and undergo fusion with one another, we can understand why in midface hypoplasia, the nose, maxilla, premaxilla, palate and dentition are all affected.

Consultation

A key component of the consult is assessing the patient’s concerns. In our experience, patients are generally concerned about:

- Aesthetics: Under-projected nose with a ptotic tip and a flat or concave facial profile. Patients generally do not point out that their perialar or premaxillary areas are retrusive. The rhinoplasty surgeon needs to bring this anatomical deficit to the attention of the patient and discuss how the retrusions will affect the outcome of rhinoplasty.

- Breathing function: There may be concomitant septal deviations leading to nasal obstruction and external nasal deviation in the middle and lower third of nose. It is important to obtain a history of previous septoplasty as that will limit the amount of septal cartilage available for grafting.

- Malocclusion: The patients may have Class III occlusion or forward-oriented upper teeth and dental crowding. A history of malocclusion, dental extractions, braces and orthognathic surgery should be taken. In addition to rhinoplasty, orthodontic treatment may be indicated for optimal cosmetic improvement. The patients should be referred to an Orthognathic surgeon and an Orthodontist for assessment and treatment of malocclusion, where indicated.

The surgeon should assess the patient’s willingness to accept various augmentation materials – autologous costal or conchal cartilage graft, homologous costal cartilage, synthetic implants such as Medpor, silicone or Gore-Tex. This is important for surgical planning. The risks and benefits of the above materials are discussed.

The surgeon should also discuss the need for adjunctive procedures to rhinoplasty such as genioplasty to reduce chin projection, or chin augmentation procedures for retrusive chin in patients who refuse maxillary advancement and mandibular osteotomies for improving the facial balance and/or occlusion.

It is emphasized to the patient that deficiency of skin may be a limiting factor in achieving the desired tip augmentation during primary surgery despite using columellar advancement flaps. This may dictate less than desired tip augmentation during primary surgery to prevent breakdown of columellar wound, and a supplementary planned tip augmentation may be necessary at a later date to achieve optimal aesthetic results.

Pertinent features on examination:

Lateral view (face):

a) Legan’s line of facial convexity (glabella-subnasale-pogonion) is negative (concave and not convex)

b) Line drawn from pogonion to subnasale is posteriorly slanted, rather than vertical or anteriorly slanted

c) Malar prominence lies significantly posterior to the nasolabial fold (5mm or more)

d) Forward-slanting upper lip

e) Lower lip may lie anterior to the upper lip

f) Pogonion may lie anterior to a vertical line drawn from nasion

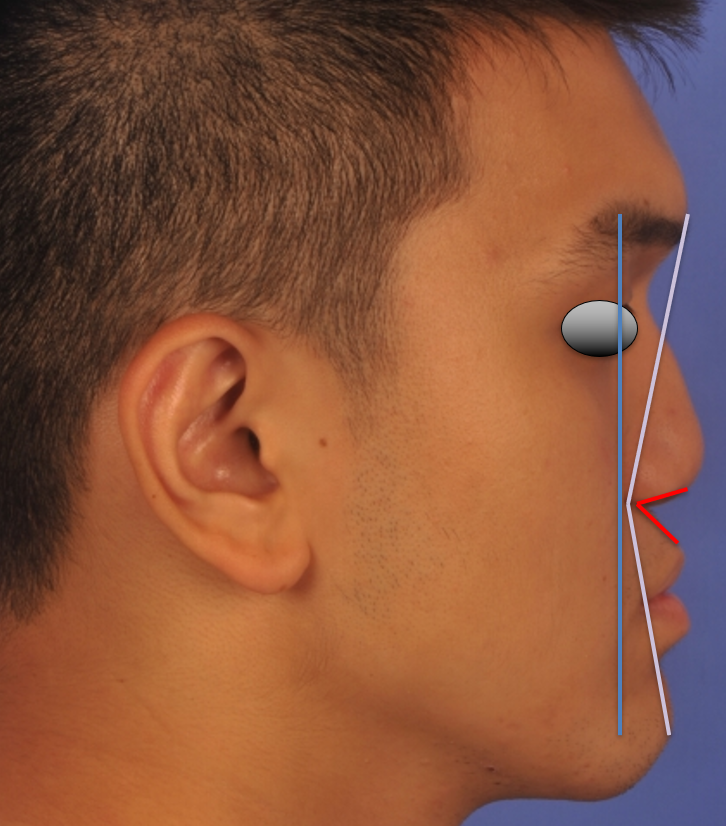

Lateral view (nose) (Figure 2):

a) Short nasal length

b) Dorsal hump, or pseudo-hump due to tip ptosis

c) Reduced dorsal height

d) Under projected tip

e) Tip ptosisAcute nasolabial angle

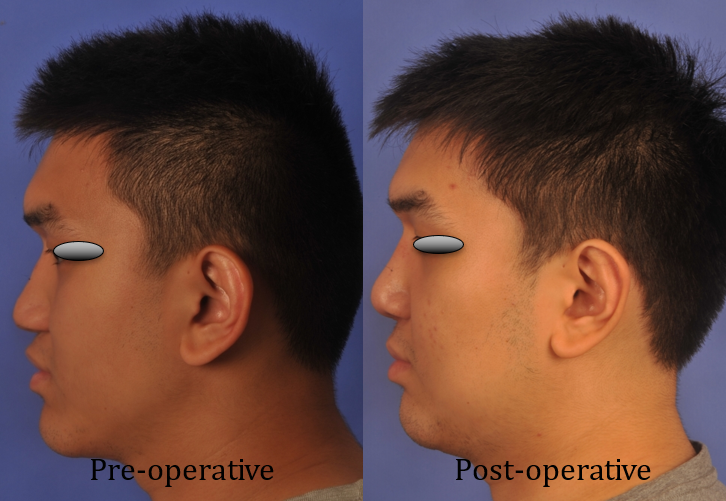

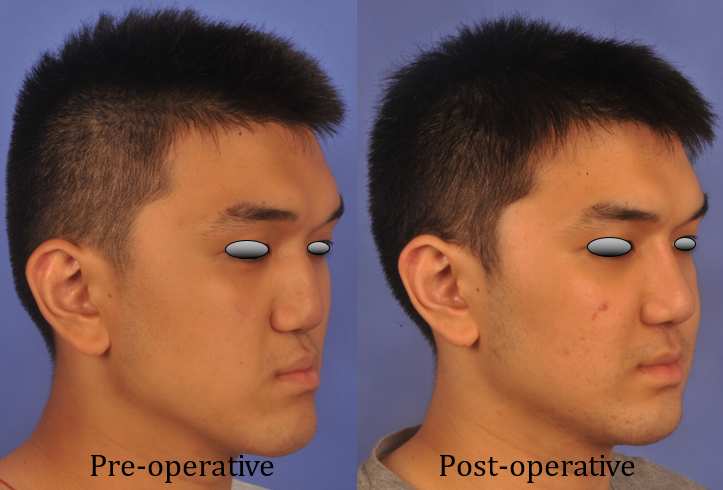

Oblique view (face):

a) Weak malar prominence

b) Perialar depression

c) Premaxillary retrusion is well appreciated on oblique view

Basal view:

a) Short columella with low columella-to-lobule ratio

b) Broad base of nose

c) Absence of columella base triangular flare

d) Bean-shaped nostrils with horizontally oriented axis

e) Less acute to perpendicular alar facial junction

Red line: acute nasolabial angle.

Yellow line: concave Legan’s line.

Blue line: Malar prominence lies posterior to a vertical line drawn through nasolabial fold.

Surgical plan

- Costal cartilage harvest

- Septorhinoplasty

a) Open septorhinoplasty approach

b) Straighten the nasal septum

c) Improve columella length, tip projection and definition

d) Radix and dorsal augmentation

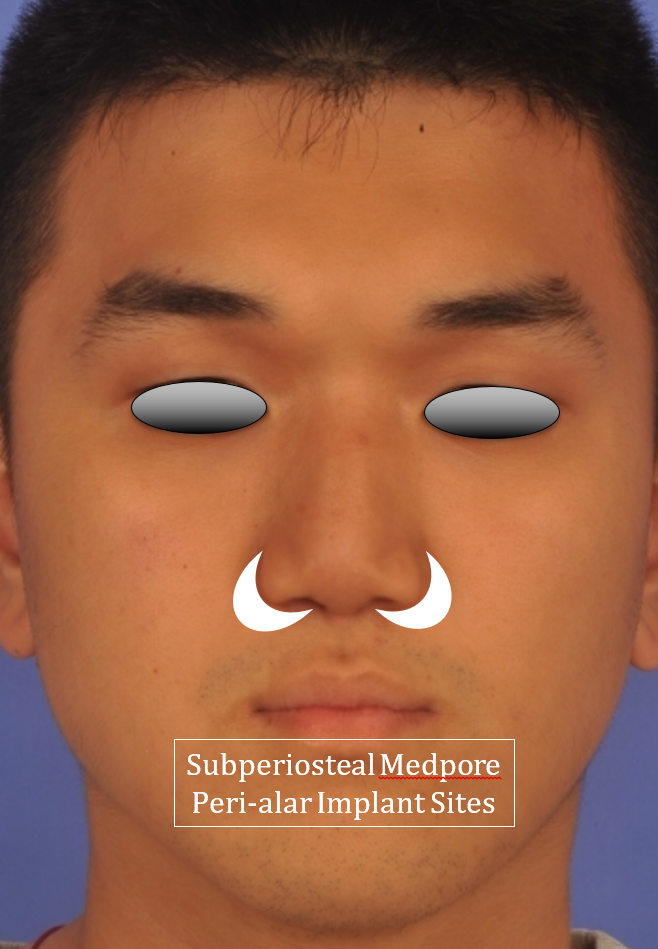

- Premaxilla and perialar augmentation

a) Sublabial approach for Medpor implant to the perialar area and lateral part of premaxilla (implant is carved to customize to patient’s unique anatomy and degree of desired augmentation). The implant is secured to the frontal process of maxilla with a titanium screw to prevent post-operative movement. This ensures an aesthetic result and reduces the risk of infection and extrusion from implant movement

b) Crushed cartilage is placed in a subcutaneous pocket in the premaxilla and base of columella for augmentation of deficient central portion of premaxilla and acute nasolabial angle

Surgical Technique

The procedure was performed under general anesthesia with oral intubation, and 2% Lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine was used for infiltration of the nose and chest. The first step of the procedure was costal cartilage harvest.

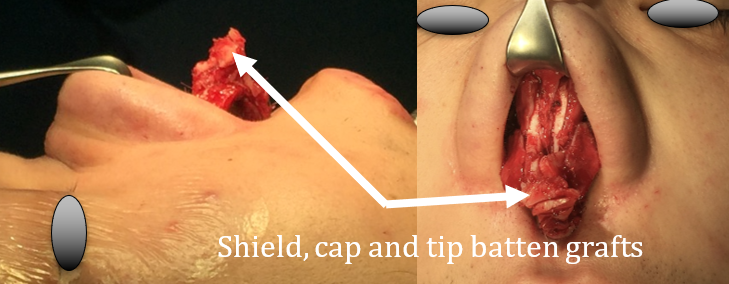

1. Costal cartilage harvest

1.5cm incision was made over the 6th rib in a skin fold. Dissection was performed through subcutaneous fat and muscles down to perichondrium of the 6th rib. The anterior perichondrium over the cartilaginous rib was preserved and the rest of the dissection was performed in a subperichondrial plane to harvest a 4-cm length of the costal cartilage. The cartilage was carved with a dermatome blade (this is our preferred blade due to its strength and length, which allows the surgeon to make straight cuts across the entire length of the rib). The carved pieces were placed in normal saline for 60 minutes to allow for warping. Straight pieces of cartilage obtained from the core were then used for fashioning a septal extension graft, extended spreader grafts, shield graft and tip grafts. The incision was sutured in 2 layers with 4-0 vicryl after inserting an epidural catheter in the wound for irrigation with Marcaine for pain control in the post-operative period for pain control.

The next step in the procedure was perialar augmentation.

2. Perialar augmentation

The upper gingivobuccal sulcus was infiltrated with 2% Lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine. A sublabial incision was performed bilaterally from canine tooth to 1 cm from the midline preserving normal cuff of central gingivo-buccal mucosa. The incision was made about 3mm from the gingivobuccal sulcus, leaving a generous cuff of buccinator muscle to allow for stronger suture closure.

A right and left paranasal Medpor implants were carved into crescent-shaped implants to conform to the perialar depressions (Figure 3). The thickness and shape of the implants was customized to approximate the depth and 3-dimensional shape of the perialar deficiency from bone to the anticipated level of the skin after correction. As a rule of thumb, a 1cm thick implant provides approximately 0.7cm (70%) of apparent increase in soft tissue height. We recommend an incremental carving of the implant to make sure that the implant is adequately customized to achieve the desired augmentation.

Through the sublabial incision, subperiosteal dissection was performed to the perialar region, without detaching the alar attachment to the bony pyriform aperture. The implant was placed in the perialar pocket and secured with a titanium screw to the frontal process of maxilla, ensuring that there is no mobility of the implant. Particular attention was given to the fact that the implant does not present as a prominence in the upper gingivobuccal sulcus after closure of the incisions.

The sublabial incision was sutured in 2 layers with interrupted Vicryl 4/0 suture to the approximate the buccinator muscle and the mucosa.

3. External Approach Septorhinoplasty

The open rhinoplasty approach was performed with an inverted-V trans-columella incision continued into marginal incisions, followed by degloving of the nose in the supra perichondrial plane over the ULCs and LLCs, and the subperiosteal plane over the nasal bones. The ULCs were separated from the dorsal septum. Bilateral septal mucoperichondrial flaps were elevated, deviated part of septum was excised, preserving 1.5cm caudal and dorsal struts.

There was a need to provide structural support to the dorsum and caudal septum, to address the tip ptosis and lack of projection. Bilateral extended spreader grafts were placed and anchored to the dorsal strut of septal cartilage with PDS 5/0 sutures. Caudal septal extension graft was anchored to the anterior nasal spine and extended spreader grafts with PDS 5/0 sutures (Figure 4). These grafts provide the structural extension to project the nose, much like the beams and columns propping up the roof. A solid cartilaginous foundation is paramount to achieve the desired tip projection. If the foundation is weak the tip will tend to lose projection due to the posterior force exerted on it while redraping the skin and soft tissue envelope and suturing the trans-columella incision.

A 3 mm cephalic trim was performed (preserving 8 mm of caudal LLC) to narrow the broad lateral crura of the LLCs (figure 5). Trans domal sutures were placed with PDS 5/0 to better define the domes. Interdomal sutures (PDS 5/0) were placed, and the domes were anchored to the newly formed anterior septal angle on the caudal septal extension graft to increase tip projection. A shield graft was fashioned and anchored to the medial crura with PDS 5/0 to address columella retraction and further increase the tip projection (Figure 6). Three cap grafts and a tip batten graft were fashioned and anchored with PDS 5/0 to further improve tip definition and projection.

The low radix combined with a prominent supraorbital ridge creates an acute nasofrontal angle, giving the illusion of a short nose in this group of patients. An onlay graft fashioned from lightly crushed costal cartilage was used for radix and dorsal augmentation for a more pleasing and balanced aesthetic result (Figure 7).

Due to the substantial amount of desired augmentation of the tip in such patients closure of the trans columella incision is under considerable tissue tension. Hence the marginal portion of the columella incision was extended bilaterally towards the sill to create a columella advancement flap to make it easier to close the incision with minimal tension on the wound edges (Figure 8).

The last step in the procedure was augmentation of the medial premaxilla and nasolabial angle.

4. Premaxillary augmentation

There are a few anatomic features to address in premaxillary retrusion:

a) A short caudal septum and columella

b) A hypoplastic anterior nasal spine

c) Bony deficit in the premaxilla

d) Forward slanting upper incisors

These factors lead to a forward slanting upper lip and an acute nasolabial angle. In addressing the acute nasolabial angle, a Korean study demonstrated that Asian patients with an acute nasolabial angle prefer a less acute nasolabial angle after correction, instead of the Caucasian ideal of 90 degrees for males and 95-105 degrees for females10 In our experience, this largely holds true, particularly in patients with premaxillary retrusion, as the forward slanting upper lip may not be completely corrected into a near-vertical position from the lateral view. To create an obtuse nasolabial angle in a case with forward slanting upper lip will lead to an upturned or unnatural-looking nose.

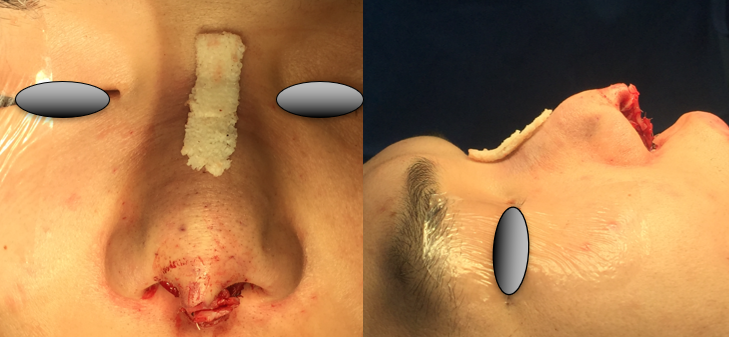

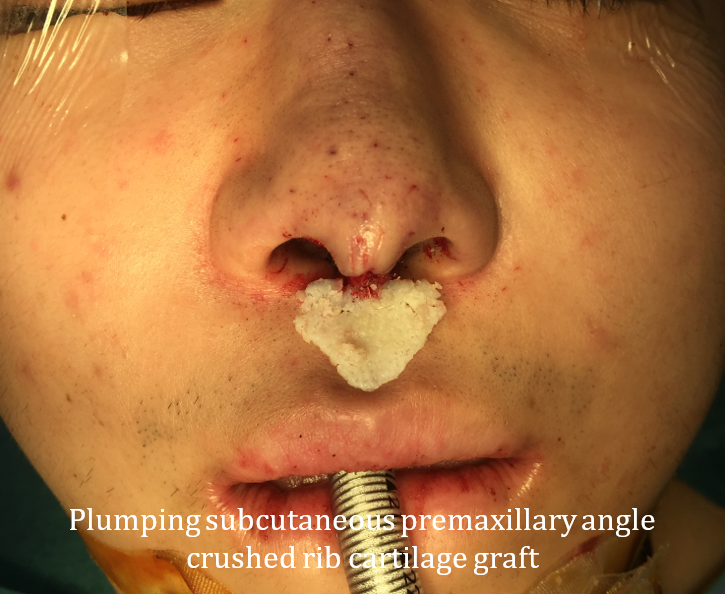

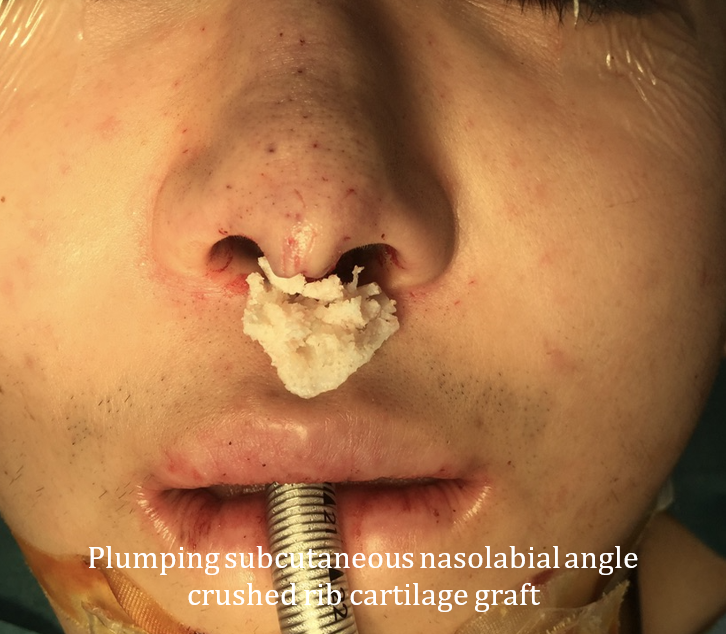

In our experience, subcutaneous augmentation of the premaxillary region provides the most consistent and clinically apparent augmentation, with the least amount of cartilage required. We convert the premaxillary forward slant to a more vertical position by correcting the lateral subalar portion with the Medpor implant placed in a subperiosteal pocket (Figure 3), while the medial premaxillary area inferior to the sill and columella is corrected with subcutaneously placed crushed cartilage grafts (Figure 9). The acute nasolabial angle was corrected with a subcutaneous crushed cartilage graft placed along the base of the columella(Figure 10). The placement of the 2 sets of crushed cartilage grafts helps to augment the bony deficit in the premaxilla and widens the acute nasolabial angle.

A subcutaneous pocked was created in the inferior portion of the columella anterior to the ill-developed anterior nasal spine and septal extension graft, the nasolabial angle and the portion of the upper lip under the sill and in the philtrum. This pocket was created through the trans columella incision and the incisions made for advancement of the inferior columella skin. The subcutaneous pocket was large enough to house the crushed cartilage premaxillary grafts. The lateral limits were at the mid alar base, accounting for the lateral extent of premaxillary deficit after placement of the perialar Medpor implant. The amount of crushed cartilage used for augmentation was adjusted to obtain the desired aesthetic result.

Closure of the marginal incisions was performed with interrupted Vicryl rapide 5/0 sutures and the columella incision with Nylon 6/0.

5. Post-operative care

We applied steristrips and a thermoplastic splint over the external nose to minimize swelling and to prevent inadvertent nasal trauma . Twice-daily nasal saline douches and gentle chlorhexidine gargle were prescribed. Oral antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanate) were prescribed for 1 week as prophylaxis against implant infection. The thermoplastic splint, steristrips and non-dissolvable sutures were removed after 1 week and nasal toilet was performed at the same sitting. Steristrips and thermoplastic splint were reapplied for another week. The patient was advised not to apply pressure to or rub the upper lip and peri-alar areas to avoid displacement of implants and grafts.

Persistent oral sutures were removed after 3 weeks. Follow-up was scheduled at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year post-operatively. Any revision or touch up surgery is ideally planned after 1 year.

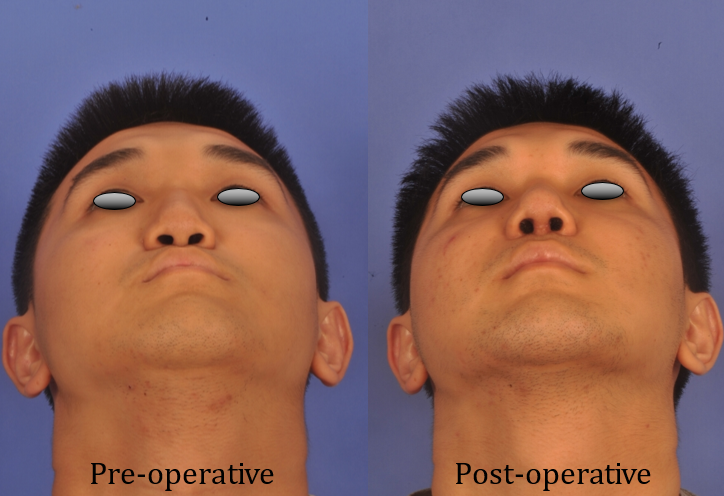

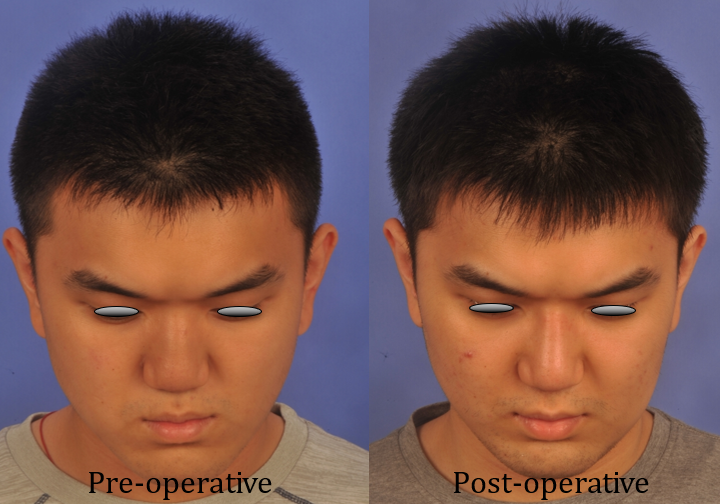

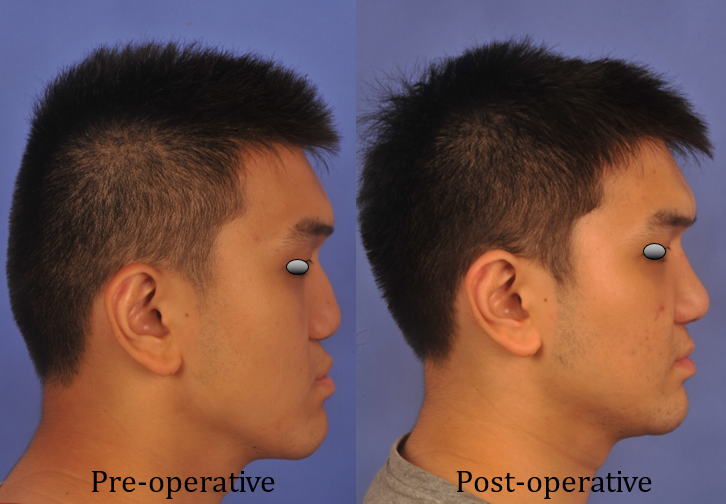

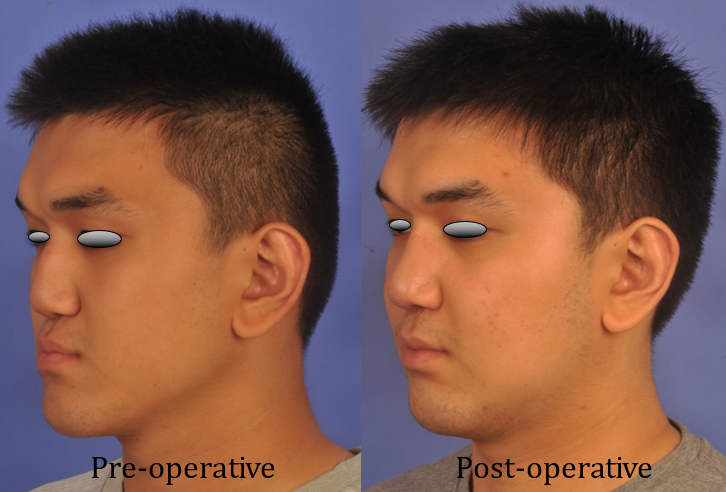

Figure11. Pre- and post-operative photos

Discussion

We present a technique of managing premaxillary and paranasal retrusion that is effective (Figure 11), leads to minimal morbidity and is replicable by other rhinoplasty surgeons. Several other techniques and approaches have been described in the management of premaxillary and paranasal retrusion and midface hypoplasia. These techniques include:

- Synthetic implants for premaxilla and paranasal deficits, including silicone, Medpor and Gore-Tex.

- Maxillary advancement through osteotomies.

Discussion on implant materials

Silicone, Medpor and Gore-Tex are commonly-used synthetic implant materials with a good safety profile11-16. They can be carved for implantation into the premaxilla and perialar regions, and more commonly for dorsal augmentation. The advantages of these materials are their relatively low cost, ease of handling, no risk of resorption, no donor site morbidity and no restriction on amount of material available for augmentation. There are also pre-shaped synthetic implants such as the Fanous silicone premaxillary implant17. As with any implants, they carry with them risks of infection, foreign body reaction, displacement and extrusion. The alternatives to synthetic materials are cartilage and bone. The advantages of autologous or homologous materials are lower risks of infection, extrusion and foreign body reactions. The disadvantages are the donor site morbidity and possibility of resorption, which can be unpredictable. One study on the use of bone vs cartilage in midface augmentation showed higher rates of secondary correction in the bone graft group and greater long-term reliability in maintaining nasal tip projection and nasolabial angles with cartilage, but both may be used depending on surgeon preference and training18. Another study comparing silicone and cartilage augmentation rhinoplasty in Binder’s syndrome found that cartilage rendered better cosmetic outcomes19.

We opted for this use of cartilage in the premaxillary area for several reasons:

- Placing a rigid synthetic implant in a highly mobile area can cause discomfort to patients and increases the risks of extrusion.

- A rigid implant is likely to be palpable by the patient in the upper gingivo-buccal sulcus due to the thin mucosa in that area. Risks of extrusion is higher due to delicate tissues in the premaxilla, namely the thin gingivobuccal mucosa and the thin nasal mucosa/skin.

- By implanting cartilage in the subcutaneous plane, we are able to effect significant augmentation with a relatively small amount of cartilage.

We opted for the use of Medpor in the peri alar area for several reasons:

- A larger amount of material is needed to produce significant augmentation. Synthetic materials limit the donor site morbidity associated with harvesting larger amounts of cartilage.

- Medpor has good osseointegration properties and hence has a lower potential for mobility and displacement. Fixation of the implants to bone using titanium screws further reduces the risk of displacement and infection.

- We are experienced with Medpor and have had no extrusions with this material in this area.

Discussion on maxillary advancement

In our opinion, maxillary advancement is a useful approach for severe midface hypoplasia, particularly if significant malocclusion is present. Tessier, Osweseger, Converse and several other surgeons have advanced the techniques of maxillary advancement for severe midface hypoplasia over the decades. The technique involves lateral cephalograms followed by cephalometric measurements and modeling to determine the extent of advancement required to achieve optimal cosmetic improvement and occlusion; osteotomies (Le Fort I, II or variants) are performed and the maxilla is advanced and secured with plates and maxillomandibular fixation20-23. Bone grafts are often used to improve the stability of the now-advanced midface.

Conceptually, it is a direct way to correcting a bony retrusion – by advancing the retruded midface. The advantages of this approach include the ability to correct malocclusion and minimizing the need for synthetic implants for augmentation (except for plates and screws). The disadvantages of this approach are the more involved surgery that requires training in maxillofacial surgery, significant blood loss, longer operative time, longer recovery time, discomfort from maxillomandibular fixation, risk of unstable fixation, early or delayed malocclusion, risk of sinusitis and injury to other structures including the orbital contents and the skull base20-23.

Rhinoplasty will usually be required if there are nasal deformities, and can be performed concurrently with the orthognatic procedure or staged. Advantages of concurrent orthognatic surgery and rhinoplasty include single anesthesia event, surgical field that is free of scarring and improved visibility. Disadvantages include lower predictability of results and higher risks to the post-operative airway obstruction. Advantages of staged procedures include better predictability of outcomes, possibility to correcting residual aesthetic or functional problems following the first procedure, while disdavantages include need for second anesthetic event and potential exposure of implants24,25.

For mild to moderate midface deficiencies, augmentation with cartilage and synthetic implants are our preferred option. For severe midface deficiencies with significant malocclusion, midface advancement should be considered.

Finally, a word of caution in the under-projected nose that requires significant augmentation – the surgeon should take care not to place the skin over the columella under excessive tension. While the columella incision may be apposed and closed with sutures at the end of the procedure, delayed dehiscence or skin necrosis may occur after suture removal (Figure 12). During rhinoplasty the surgeon must augment the tip projection in an incremental fashion not only to assess the affect of this manouvre on tip aesthetics but also to assess the amount of tension exerted on the skin before proceeding with more augmentation. The lateral columella incisions can be extended down to the nasal sill to crate an advancement flap to decrease wound tension during closure of transcolumellar incision. Any blanching of tip skin during tip augmentation should prompt the surgeon to compromise and accept a lesser degree of tip projection with the aim of minor touchup to improve tip projection at a later date. Sometimes, dehiscence may not occur but the columella incision may stretch out and become an atrophic scar.

In such a situation, the scar can be excised and the advancement procedure performed after 6 to 12 months. We also recommend placing the transcolumella incision nearer the base during the primary procedure to prevent scar becoming visible after augmentation.

References

- Chan EKM, Soh J, Darendeliler MA et al. Esthetic evaluation of Asian-Chinese profiles from a white perspective. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.03.038

- DH. Enlow, C Pfister, E Richardson, et al. An Analysis of Black and Caucasian Craniofacial Patterns. The Angle Orthodontist 1982;52(4):279-287.

- Von Binder KH. Dysostosis maxillo-nasalis, ein arhinencephaler missbildungscomplex. Dtsch Zahnaerztl 1962;17:438.

- Chummun S, McLean NR, Nugent M, et al. Binder syndrome. J Craniofac Surg 2012;23:986–990.

- Holmström H. Clinical and Pathologic Features of Maxillonasal Dysplasia (Binderʼs Syndrome). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(5):581. doi:10.1097/00006534-198611000-00003

- McNamara JA. Influence of respiratory pattern on craniofacial growth. Angle Orthod 1981; 51(4):269-300.

- Bresolin D. Shapiro PA, Shapiro GG, Chapko MK, Dassel S. Mouth breathing in allergic children: Its relationship to dentofacial development. Am J Orthod 1983;83(4):334-340.

- Sadler TW. Head and neck. In: Langman’s Medical Embryology. 14th edition. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 2018.

- Gray H, Lewis W. Anatomy Of The Human Body. 20th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1918:161.

- Choi S, Kim S, Lee H, Chang D, Choi M. Esthetic Nasolabial Angle according to the Degree of Upper Lip Protrusion in an Asian Population. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2018;32(1):66-70. doi:10.2500/ajra.2018.32.4485

- S Deshpande, A Muroli. Long-term results of high-density porous polyethylene implants in facial skeletal augmentation: An Indian perspective. Indian J Plast Surg. 2010 Jan-Jun; 43(1): 34–39.

- Karnes J, Salisbury M, Schaeferle M at al. Porous High-density Polyethylene Implants (Medpor) for Nasal Dorsum Augmentation, Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2000: https://doi.org/10.1067/maj.2000.104664.

- Dhirawani RB, Singha S et al. High-density polyethylene material versus autogenous grafts in craniofacial augmentation procedures. Ann Maxillofac Surg. K Agarwal, 2019;9(1):10-14.

- Byrd HS, Hobar PC. Alloplastic nasal and perialar augmentation. Clin Plast Surg 1996;23:315– 26.

- Godin MS, Waldman SR, Johnson CM. Nasal Augmentation Using Gore-Tex: A 10-Year Experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1(2):118–121. doi:10.1001/archfaci.1.2.118

- Quatela V, Chow J. Synthetic Facial Implants. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2008;16(1):1-10.

- Fanous N, Yoskovitch A. Premaxillary augmentation for central maxillary recession: an adjunct to rhinoplasty.Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am 10 (2002) 415–422

- Gewalli F, Berlanga F, Monasterio et al. Nasomaxillary Reconstruction in Binder Syndrome: Bone Versus Cartilage Grafts. A Long-Term Intercenter Comparison Between Sweden and Mexico. J Craniofac Surg 2008;19(5): 1225-1236.

- Tian L, You J, Wang H et al. Comparison of Two Different Grafts in Nasal Framework Reconstruction of Binder Syndrome. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2017;28(6):1413-1417.

- Tessier P. Total Osteotomy of the Middle Third of the Face for Faciostenosis or for Sequelae of Le Fort III Fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;48(6):533-541.

- Tessier P, Tulasne J, Delaire J et al. Therapeutic aspects of maxillonasal dysostosis (binder syndrome). Head Neck Surg. 1981;3(3):207-215.

- Posnick J, Tompson B. Binder Syndrome: Staging of Reconstruction and Skeletal Stability and Relapse Patterns after LeFort I Osteotomy Using Miniplate Fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(4):961-973.

- Fariña R, Valladares S, Raposo A, at al. Modified Le Fort III osteotomy: A simple solution to severe midfacial hypoplasia. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2018;46(5):837-843.

- Sun A, Steinbacher D. Orthognathic Surgery and Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(2):322-329.

- Veeramani A, Sawh R, Steinbacher D. Orthognathic Surgery and Rhinoplasty to Address Nasomaxillary Hypoplasia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(5):930-932.