Introduction

The Continent of Asia consists of several races and ethnic nasal shapes. Asian noses vary in height and width from the noses of the Indian subcontinent with their Caucasian nasal features, the Persian/Middle Eastern nose with their Mediterranean type features to the relatively smaller East Asian type Korean – Chinese nose and the Asian Malay nose of south–east Asia.

The scope of this chapter discusses Asian rhinoplasty surgery and the techniques used. The Asian type of rhinoplasty surgery which is the focus of this chapter is not synonymous with every rhinoplasty surgery performed in Asia on Asians, unlike what the title might suggest.

The Causasian and Mediterranean type noses of the Asian Continent usually require reduction and tip refinement techniques.These are often described in Western rhinoplasty surgery books and this type of rhinoplasty does not form the select discussion here. This chapter will focus more on the requirement for the more smaller East Asian and Asian Malay type of noses where augmentation strategies to raise the nasal profile are usually employed .

Rhinoplasty trends in Asia

Rhinoplasty in Asia is fast increasing in its popularity. With an improving economy, many clients are looking to enhance their looks for personal reasons, socio-economic competitiveness in the job market place and /or peer influence from the local Asian/international film and music media.

Asian rhinoplasty techniques range from rhinoplasty by injectables to closed and open approach rhinoplasty procedures. These techniques have been described in the literature and performed in the West. However the surgical pendulum for the Asian nose is mostly about augmentation, instead of reduction. Augmentation strategies, materials and techniques form the volume of Asian practice.

This chapter will outline the varied techniques and the underlying essence of Asian rhinoplasty. An additional subchapter is dedicated to the ancient Chinese face reading philosophy and examines for the uninitiated reader how that could influence Asian rhinoplasty decision making for their clients.

The Asian nose

The archetypal Asian nose discussed in this chapter is typified by the Asian Malay nose or the East Asian (Chinese, Japanese and Korean) type of nose. There is indeed a spectrum of these noses, with northerners e.g. from north China and Korea having higher dorsums compared to their Asian southerners with lower dorsums. The Asian nose primarily discussed here is typified by petiteness and flatness. The overall mid-facial bony components and nasal septum can be thought of as being “underdeveloped”. Hence the radix tends to low with a low rhinion and low mid-third dorsal profile height. The shorter nasal septum with a less projected anterior septal angle results in a nasal tip that lacks projection. A less projected tip, in turn, is more rounded with less tip definition. There usually is also relatively thicker skin overlying the nasal tip and lobules. The ala basal width is also wider.

From the basal view, the nostrils of the Asian nostril appear more rounded compared to the tear-drop appearance of the Western nose. This is due to the lack of projection. The columella may appear short and retracted, lacking support from the caudal septum. Internally, the cartilaginous septum of the Asian nose is generally less generous which explains the deprojected tip; this smaller size will impact upon the availability of septal donor material too. The medial and lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages are smaller, weaker and softer than Caucasian noses, and tend to have a more oblique to vertical lie. The upper lateral cartilages are similarly small in size too.

Overall the description of the Asian nose is one of petiteness and flatness. Asian clients seeking rhinoplasty therefore not surprisingly request for higher radixes and dorsums with more tip projection and narrower alar bases. The contemporary trend is to request for augmentation and tip projection whilst retaining their Asian ethnicity.

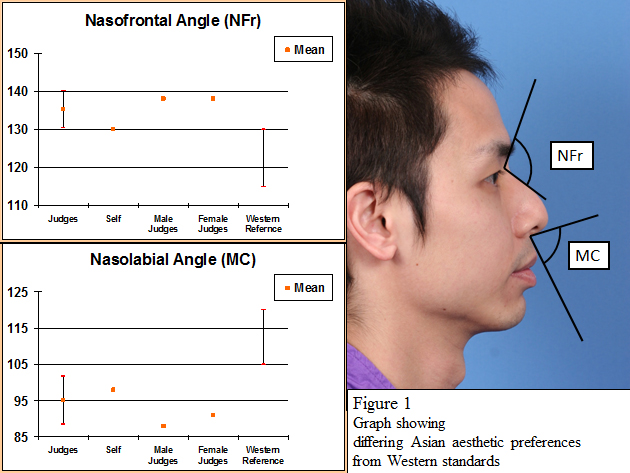

In a small sample study by the authors at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, nasal pictures of Chinese male and female individuals were evaluated to determine their aesthetic outcomes.

These subjects with a group of independent local Chinese male and female judge observers, were requested to freely simulate with computer software, the nose they would wish to have. There was notable agreement and concordance on the final nasal profile simulated i.e. everyone had the same aesthetic endpoint.

What this sample work demonstrated was, whilst all these Asian clients and peer judges preferred higher radixes and dorsums with greater tip projection, the measured parameters differed significantly from accepted Western aesthetic references (see Figure 1 – Graph of Asian aesthetics). This suggested that even though Asian individuals wanted a pointier and higher nose, they wanted to retain their “Asian” sense of aesthetics.

With this in mind, the following subchapters discuss in more detail the commoner techniques for Asian rhinoplasty surgery. The discussion below is not intended to be comprehensive due to surgeons’ preferences, the wide availability of products and techniques. Readers should instead focus on the underlying principles to permit a more flexible practice of Asian rhinoplasty, as this field and product technology develops.

Principles of Asian rhinoplasty

The final result of any Asian rhinoplasty procedure is ultimately a function of the client’s preference, the local/racial aesthetic sense, the available donor/synthetic materials and the surgical planning and execution. The surgeon is often faced with the dilemma of choosing from the different techniques and available materials in achieving the desired result for his client with a minimal complication rate.

As mentioned previously, the typical Asian nose lacks tissue in general, both internally as well as externally. The principle of approach for the Asian rhinoplasty is to augment the nose i.e. to increase its radix height, its dorsal height and to project the tip. Tip up-rotation and excessive nostril show should generally be avoided as discussed in our later subchapters. In order to add to the existing structure, additional augmentative implant materials are required. A list of augmentative implant solutions are listed below. This list is illustrative and not intended to be exhaustive; it will change as improved product technology comes to the market.

Autologous grafts

- Septal cartilage

- Conchal cartilage

- Costal rib

- Autologous fat

- Fascia e.g. temporalis fascia, tensor fascia lata

- Bone eg iliac crest, calvarium

- “Diced cartilage” in temporalis fascia

Homografts

- Tutoplast (Processed human fascia)

Xenografts

- Permacol (Porcine dermal collagen)

Alloplastic materials

- Rigid

- Silicone

- Medpor (Porous polyethylene)

- Semirigid

- Goretex (Expanded polytetrafluoroethlyene)

- Soft

- NASHA (Non-acidic synthetic hyaluronic acid)

- PAAG (Polyacrylamide gel)

Autologous cartilage is generally preferred with their lower complication rates. Donor site morbidity and resorption are issues to be addressed with the patient before surgery. The nasal septal cartilage is regarded as the best implant option for rhinoplasty as a structural or camouflage graft. However in the Asian patient, there is usually insufficient septal grafting material available to achieve the augmentation desired.

So the surgeon tackling Asian rhinoplasties should familiarize themselves with alternative autologous conchal cartilage, autologous costal rib and synthetic material solutions. A single-material solution may not suffice and a combination-material solution may be necessary. The different options are discussed in more detail below. The alloplastic materials can also be categorized as above based on their respective consistency. Their rigidity or softness confers different structural and aesthetic outcomes, and understanding these properties further shapes where they are best applied in the Asian nose

Preoperative evaluation of the Asian nose

Before any surgery, a preoperative evaluation of the Asian client’s expectation is critical for a good outcome. An evaluation on the functional and/or cosmetic objective of the rhinoplasty should be discussed with the patient. Wherever possible, it should include the following:

An assessment of the nasal characteristic of the patient

The Asian nose usually has a low radix, low dorsal height, weak lower lateral cartilages, de-projected tip, columella retraction, narrow ala base and thicker skin overlying the supratip & tip.

An assessment of the Asian clients’ expectation

Asian patients usually request a higher radix and dorsum and more projected tip. Counseling should define to the client about his/her functional and cosmetic expectation of the surgery so that a tailored solution can be offered. The use of simulation software is a powerful tool to help the patient better visualize and understand the expected aesthetic outcome. This preoperative simulated visual tool is important as more and more Asian clients are increasingly more sensitive about retaining their ethnic identity after rhinoplasty.

A discussion about the operative process and risks

A full discussion about the surgical process including incisions, donor graft sites, implant materials and their complications should be undertaken. It is possible that several combinations of grafts and implants can be used to achieve the same result so the client should be responsibly counseled as to the best approach that minimizes future problems.

Autologous cartilage for Asian rhinoplasty

The advantages of using autologous cartilage grafts are

- the low infection rates,

- negligible risk of crossover infection associated with donor tissues

- and the relative cheap costs.

The disadvantages are

- donor site morbidity

- and the partial resorption of the grafts which can occur over time.

In many cases, most Asian patients do not tend to be overly concerned when faced with septal or conchal cartilage donor harvesting. A lengthier discussion usually is required when autologous rib harvests are discussed as the reconstruction material of choice.

As discussed earlier, the best material for augmenting the Asian nose is the septal cartilage. However this is usually insufficient in the Asian nose unless the requirement is only for minimal grafting volume e.g. a columella strut, a camouflage fill graft or a shield-cap graft. Hence alternative options include conchal and autologous rib cartilages.

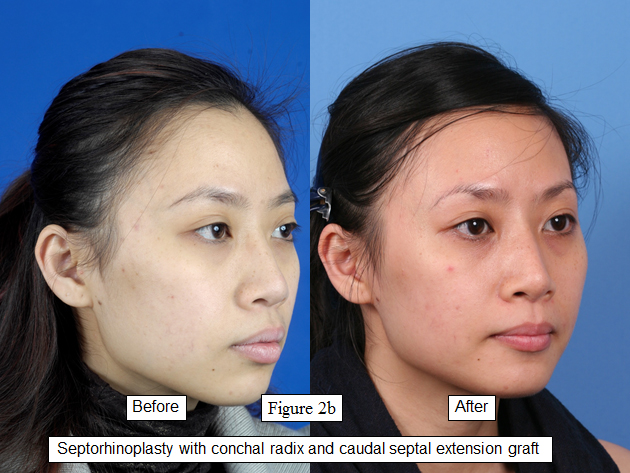

The conchal cartilage is generally softer and curved. They do not respond as well to crushing or morselisation and fragment easily. Conchal cartilage is usually best used as camouflage and cap grafts; their natural convexity can be used to further enhance the nasal shape. They can also be used as septal extension grafts although the surgeon should take caution to use ‘straighter ‘ conchal grafts ( see Figures 2a – c).

Autologous rib cartilage is plentiful for the demands of Asian augmentation. It remains the most useful and readily available source of autologous material for the Asian type augmentation rhinoplasties. Usually the 6th costal rib is used and harvested through an infra-mammary crease incision; additional rib grafts can also be taken from the adjacent 7th rib through the same incision.

Autologous rib grafts are however well known to have a tendency to warp especially when the rib has been trimmed and sculptured (Toriumi et al). This warping tendency should be monitored throughout the operative carving process. Ribs are placed into a saline-antibiotic mixture and tendencies to warp are usually evident within 30 minutes. The surgeon can then decide to use stable, un-warped rib grafts for septal extension grafts or in some cases, tailor the placement of a warped rib graft to use the curvature to the best advantage of the effect required.

To further minimize warping problems, the central portion of the rib is preferred to the cortex of the rib which has a tendency to warp more. Overall autologous rib grafts are an excellent choice in Asian rhinoplasty. Augmentation strategies usually require a significant amount of cartilage beyond what the nasal septum and ears can effectively provide for.

Alloplastic materials for Asian rhinoplasty

The augmentation requirements for Asian rhinoplasty surgery have naturally resulted in the widespread use of alloplastic implants (Berghaus et al). Alloplastic implants provide the surgeon and patient with unlimited access to material without the need for donor site morbidity, potential resorption or cross-infection hazards. Costs, implant infection and extrusion remain the counterbalancing issues to this clear advantage.

Synthetic gels are commonly used for rhinoplasty as injectable augmenters and fillers. They have replaced the traditional silicone and Teflon paste injections though these remain in use in some areas. Their commercial availability and low skill set technique make them extremely popular especially amongst non-surgical cosmetic practices.

Alloplastic implants e.g. silicone, porous polyethylene Medpor and Gore-Tex, are ideal ingredients for augmentation rhinoplasty. They can be sculptured, do not deform or resorp and their rigidity resists the shrink wrapping process well. Hence they are well suited to form the aesthetic lines for a beautiful rhinoplasty e.g. brow-tip line, the para-lateral waisting of the nasal dorsum, etc., and yet remain strong enough for subtle features to stand out against the relatively thicker skin of the Asian nose.

Injection rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasties with injectable fillers are very popular in Asia and are used extensively. The advantages of injection rhinoplasty include:

- Short learning curve for clinicians

- Minimal tooling necessary

- Inexpensive injectables

- Local anesthetic procedure

- Quick operative time

- Immediate result

- Per-operative client defined endpoint

- Minimal postoperative downtime for patient

The idea of a simple local procedure with immediate results is very attractive to the Asian clients. Furthermore the down time is minimal; this minimizes the social exposure and questioning that some Asian clients may not welcome as plastic surgery on the nose remains a taboo in some Asian communities. The traditional injectables e.g. silicone gel and Teflon paste are generally falling out of favor due to their associated and recognized complications. The newer synthetic NASHA and PAAG injectables are increasingly being used. The skill-training time required for a clinician is very short and hence, many general practice clinicians have embraced this practice. Coupled with the marketing forces, this area of rhinoplasty has increased significantly.

The injection rhinoplasty technique depends primarily on:

- the desired aesthetic result and

- the injectable filler used.

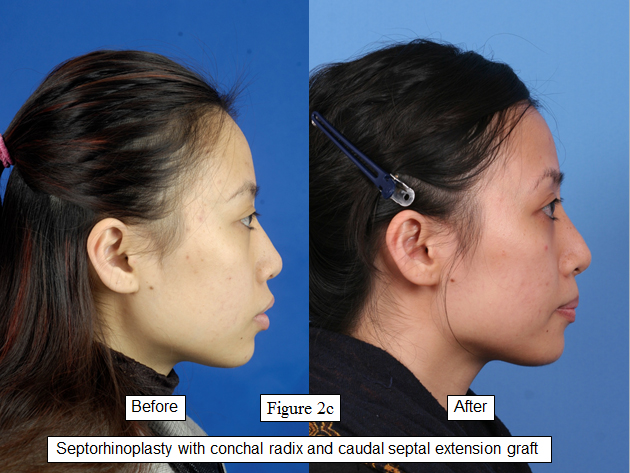

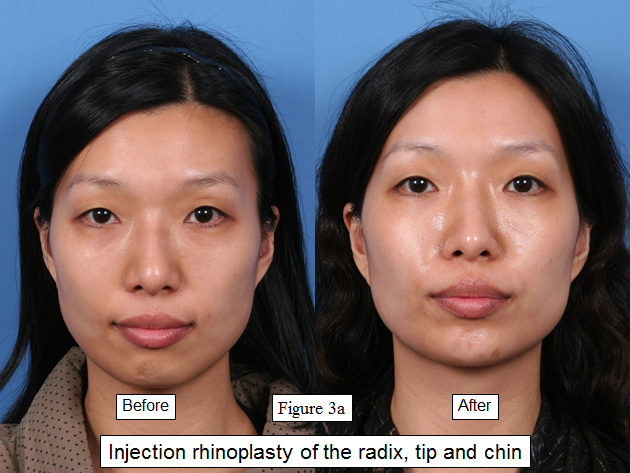

It can be employed either as:

- a primary injection rhinoplasty procedure to augment the nose or

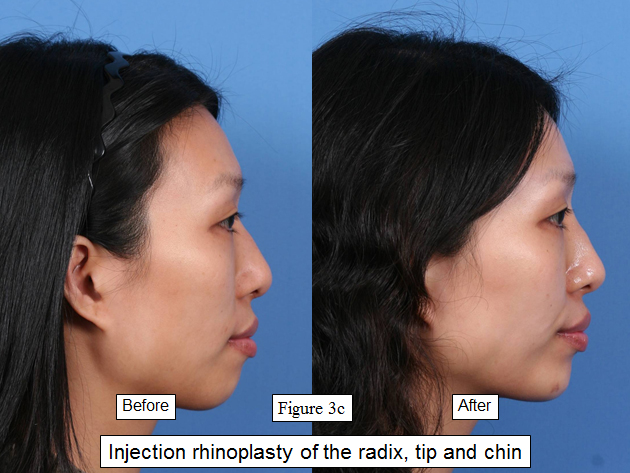

- as a secondary procedure to enhance a surgical rhinoplasty result (See Figures 3a-c)

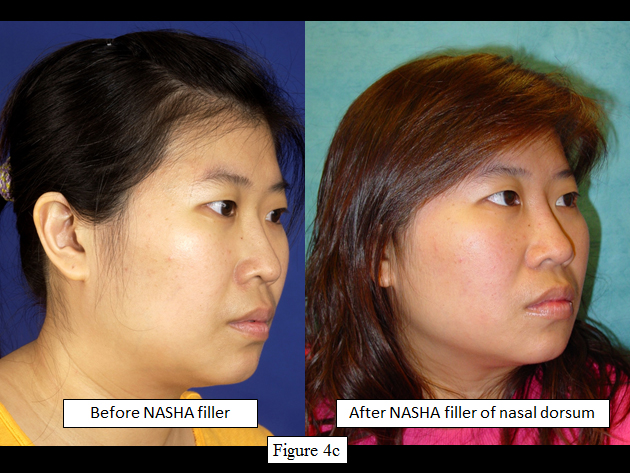

- as a secondary procedure to “salvage” aesthetic complications of septoplasty or rhinoplasty (see Figures 4a-c)

After adequate local anesthesia (topical EMLA and infra-orbital nerve block) and antiseptic cleansing of the face, the injectable is delivered into the subdermis or deeper, to augment the radix, dorsum and tip accordingly. A primary advantage of this approach is that the client can view the surgery in progress to help the surgeon define his/her own aesthetic endpoint. There will undoubtedly be tissue edema associated with the injection, which may add to the augmentation inadvertently. Hence a review of the patient a week after the procedure would be wise for any further touch-ups as required.

In the authors ‘opinion (GS & FW), we prefer to start by injecting onto the deep supraperiosteal plane with depots of filler to augment the nose and to raise the radix and dorsal profile. These depots of injection are kept in the desired augmented midline and paramedial injections are very judiciously taken to minimize the width of the augmentation. This is to ensure that the augmented soft tissue remains narrower in width. This is more in keeping with the usual Asian aesthetics of petiteness, and even whilst augmenting the nose, this illusion of petiteness is maintained. A judicious and smaller amount of subdermal injectable fills can then be added accordingly thereafter.

We preferred this in contrast to described subdermal fern leaf or reticular pattern injection techniques. These more superficial subdermal depot techniques would certainly create a stronger and more rigid soft tissue dorsum envelope. However it also adds to the nasal width which detracts from the Asian nasal concept of petiteness.

The surgeon and patient should also note that injection rhinoplasty techniques do not confer any functional advantage for the patient whatsoever as it does not inherently improve structural rigidity or structural width of the nasal framework. Furthermore as elastic tissue forces and gravity begin to exert their influence on these injected filler depots, the injected compartmentalized gel has to take on a more spherical shape to better resist these compressive forces. Hence from an aesthetic point of view, the result would be more an appearance of rounded fullness and rounded edges at these augmented areas. It would not be entirely possible to achieve a sharp and definable edge that would highlight the nasal contour as one can get from more rigid surgical implants e.g. ePTFE (Gore-Tex) or porous polyethylene (Medpor) implants.

Whilst simple, injection rhinoplasty is not without its risks. These include:

- Soft tissue infection

- Soft tissue necrosis

- Hypersensitivity reaction to the specified injectable filler

- Capsule formation

- Granuloma formation

- Ocular complications

- Complicated surgical revisions due to deep fibrosis

Management of these complications would include removal of the injectable filler, antibiotic therapy and supportive treatment as necessary. The removal of these fillers is not simple. The injectable depots would be intimately distributed in the fibrous tissue of the nose and surrounded by inflamed scar tissue. Complete removal is preferred in any complicated injection rhinoplasty and an open approach rhinoplasty may be deemed necessary to facilitate this.

Choice of injectable

There are many available injectable fillers on the market and can be broadly considered under the following category:

- Autologous injectables e.g. autologous fat

- Reversible NASHA injectables e.g. Restylane, Juvederm

- Permanent injectables e.g. Teflon paste, silicone gel, PAAG

Autologous fat is naturally preferred but the unpredictability of fat globule survival rates and donor site morbidity remain issues for the patient. Autologous fat harvesting, whilst relatively simple with specialized harvesting needles and centrifuge, adds to the cost of the procedure which may be prohibitive in some Asian clinical settings.

Permanent injectables are often preferred by patients who select injection rhinoplasty as their choice of treatment. This obviates the need for repeat injections every nine to twelve months. From a point of view of complications, all synthetic injectables carry similar risks of infection with more specified hypersensitivity and granuloma formation specific to the product used.

In the authors’ opinion (GS, FW), reversible injectables should not be disregarded. Their advantage lies in their reversibility and can be outlined as below:

- A reversible injectable is a good first line rhinoplasty trial that helps the patient to ultimately understand what they want and the personal and social implications of their facial enhancement trial. This is true even when simulated postoperative pictures have been employed in the counseling process. For the next treatment session, they can then deliberately choose to use a second permanent injectable, to convert to a surgical implant approach or not to undertake any future rhinoplasties.

- An unsatisfactory aesthetic result or over-injection will not last

- An overenthusiastic young client, eager for a rhinoplasty, will not have cause to regret for a lifetime if a reversible injectable is offered as the first injectable line of filler

- If there are signs of sluggish / lack of capillary refill due to inadvertent over-injection of NASHA, impending dermal and soft tissue necrosis is a risk. Especially prevalent areas are the nasal tip and areas of thin skin. Immediate aspiration removal of the NASHA with injection of hyaluronidase can be implemented.

The caveat to injection rhinoplasty is that some subdermal scarring will invariably occur in the injected tissue planes. This can complicate future rhinoplasty surgery and make them unpredictable and more difficult to do. Clients should be advised accordingly.

Silicone implants

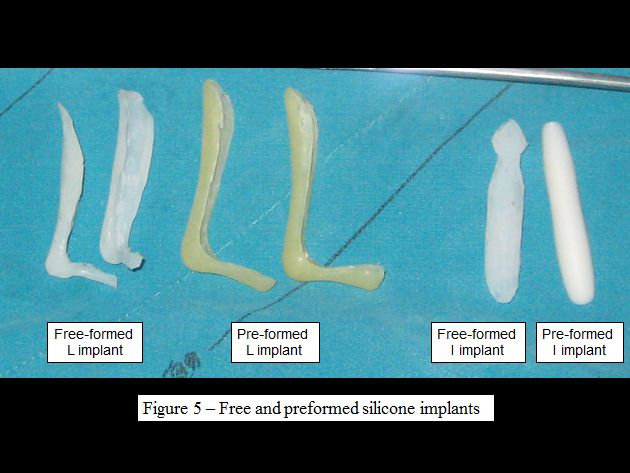

Silicone implants have been traditionally used to augment Asian noses. They remain in use today as these implants are relatively inexpensive. Silicone nasal implants are available as:

-Free-form silicone implants (carved from silicone blocks by the surgeon)

-Pre-formed silicone implants

These implants (see Figure 5) are shaped either as L-shaped struts (which provide for dorsal height, more tip projection and caudal septal extension) or as I implants (which provide primarily for dorsal height augmentation and some tip projection) as in Figure 6.

Silicone implant surgery is usually performed under local anesthesia. Depending on the implant type and the aesthetic outcome, these implants can be inserted through a marginal or rim incision. These implants are then placed into a pocket made just superficial to the dorsal nasal framework. For the L-strut implants, a pocket just caudal to the caudal septum is also fashioned for the shorter component of the L strut (see Figure 7). An intercartilaginous incision can also be used with a retrograde approach to establish any caudal septal pocket as necessary.

Pre-formed implants have a beautifully carved and smooth surface finish, and are the ideal silicone implants. In Asia where clients are price-sensitive, free-form silicone implants are more economical. Free-form silicone implant surgeons should be careful to ensure a smoothly carved implant especially for clients with thinner skin of the nasal dorsum (see Figure 8). This guarantees that silicone surface irregularities do not show nor are they easily palpable.

Implant infection and extrusion rates are well reported in the literature (Pak, Tham). Longer term extrusion of silicone implants can be minimized by ensuring adequate soft tissue coverage of the implants and implant placement with minimal soft tissue tension.

Autologous fat graft rhinoplasty

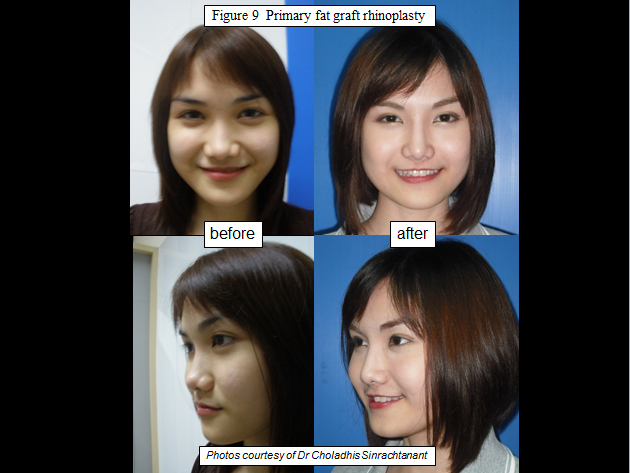

Autologous fat can be used to augment the dorsum of the nose. It has been used as harvested autologous fat globules as well as an injectable autologous fat after harvesting with e.g. a Coleman needle. It has all the above mentioned advantages and disadvantages of autologous tissue grafts. Due to its soft and pliable texture, autologous fat does provides a very natural and soft contoured look, and is excellent camouflaging filler (see Figure 9).

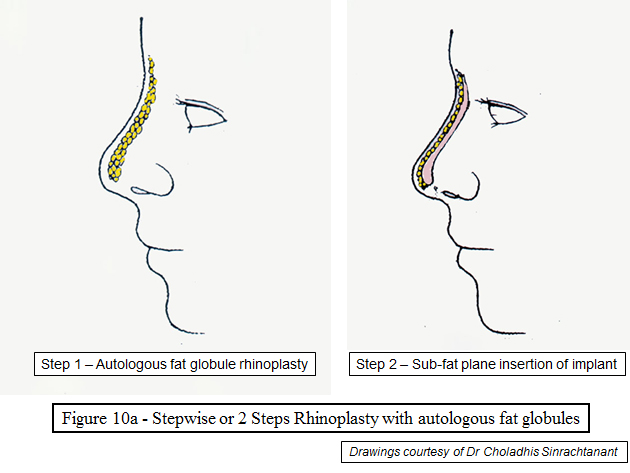

The senior author (CS) recommends autologous fat globules for primary rhinoplasty either as the sole augmenting agent, or in combination with a second stage silicone implant in a two stage stepwise procedure. In the latter technique, the autologous fat acts as a perfect soft contoured fill (see Figure 10). However its application as a salvage implant filler, in the event of a dorsal implant infection and extrusion, is the option of choice for our author CS.

In the author’s (CS) opinion, autologous fat globules form the best option for the treatment of any infected and extruding silicone implants. In the event of impending extrusion, the nose is re-explored and the thickened (ex-silicone implant) cavity lining is removed as best as is possible.

The cavity is irrigated with an antibiotic solution. The de-augmented nose should not be immediately closed as healing and future shrink-wrapping will cause extensive deep tissue scarring and contractures of the dorsum and tip cartilages. Future revision rhinoplasty will prove extremely difficult to correct well. Autologous fat gobules, harvested from the abdomen or axillae, are inserted immediately into the cavity as a biological augmentative implant (see Figure 11).

It is a natural product and resists infection well. Following successful restitution of the infection with a layer of dorsal fat globules, further future dorsal augmentation can be undertaken as a two-step rhinoplasty, but only if absolutely necessary, and preferably with further autologous rib.

Porous polyethylene Medpor implants

This is a rigid implants material that resists shrink wrapping well. Its porous surface allows blood vessels and connective tissue to grow into the implant; this “vascularises” the implant. In addition the pore size of the implant is < 1µm; this is smaller than the dimension of bacterial organisms. Together the pore size barrier and vascularity helps to prevent infection.

Adequate soft tissue coverage over all porous polyethylene surfaces is imperative to prevent complications of infection and extrusion (Berghaus et al). In the authors’opinion, clients with thicker nasal skin would be better suited as Medpor implant candidates when compared with thinner skinned individuals. The Medpor implants are used for dorsal grafting and columella struts (Romo et al). They can be easily trimmed to size with the scalpel. Due to their rigidity, they are easy to use and quite firm to the touch beneath the tissue coverage.

Medpor implants are however not as soft as, for example, silicone implants. Hence fine per-operative sculpturing of the porous polyethylene implant is not as easily performed and the use of cutting or diamond burr drills for sculpturing should be avoided as they seal off the porous surface.

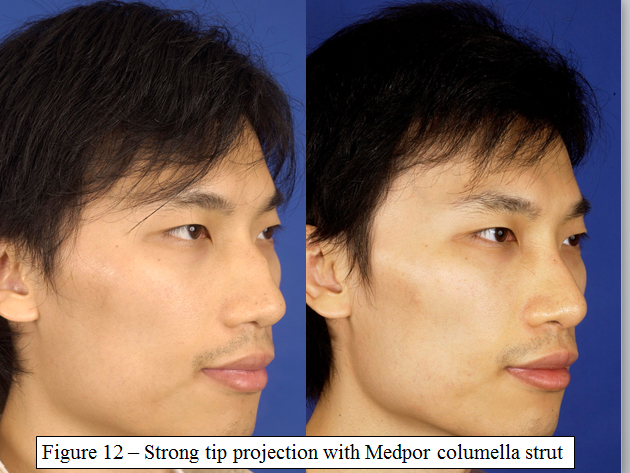

The implant is usually impregnated in a Betadine-saline solution prior to insertion, to further minimise bacterial soiling. Medpor implants are ideal for structural grafting of the Asian columella. They provide strong tip support and projection (see Figure 12), improving the functional airway as well as the aesthetics.

A pocket is fashioned between the meso-crural cartilages of the lower laterals into which the Medpor columella sheet is inserted; the implant sheet is then secured with ample soft tissue coverage. A word of caution for the patient – whenever Medpor implants are applied in the flexible lower third of the nose, the natural flexibility of the lower nasal tip will be impaired with a firm and relatively unyielding nasal tip to the touch as the final result.

Medpor implants are also suitable for dorsal augmentation in Asian rhinoplasty. Dorsal radix augmentation, where there is good soft tissue coverage, is excellent. The Medpor implant is placed in a subperiosteal pocket that is the usual 10% larger than its dimension; this prevents excessive postoperative implant migration. The conferred rigidity, when felt through the skin, of the Medpor radix implant mirrors that of the expected underlying nasal dorsum, and appears quite natural at this site.

The authors have also successfully applied Medpor dorsal implants to augment the dorsum e.g. for saddle nose deformity. However clinicians should probably exercise greater care whenever using, or extending, the Medpor implant over the dorsal aspect of the lower third of the nose i.e. in the supratip area. The relatively flexibility of this area of the nose, the closer proximity of the implant to the incisions and the relatively thinner mucosal tissue coverage, can potentially lead to higher implant loss rates here. Care should always be taken to ensure adequate soft tissue coverage over the implant at all times.

In the event of infection with overlying erythema, appropriate antibiotic therapy should be instituted. Implant removal is necessary if there is no response to the antibiotic treatment or impending implant extrusion. Sharp dissection over the implant surface is required with a scalpel blade or sharp iris scissors, to divide the micro-vessels and connective tissue that would have grown in continuity into the implant body through the surface pores.

Gore-Tex implants for Asian rhinoplasty

Gore-Tex, or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE), is a very popular alloplastic material used currently in Asian rhinoplasty. It is relatively inert with a low implant infection and reaction rate. Its semi-rigidity allows it to be easily sculptured and worked by the surgeon. The final implant mould also resists the shrink-wrapping forces sufficiently to allow the underlying implant features to be subtlely evident beneath the soft tissue nasal envelope.

The ePTFE implant can be used as individual sheets or preformed stacked sheets of varying thickness. For thinner ePTFE sheets, the surgeon can surgically stacked the sheets to their required height and transfixed the sheets prior to sculpturing and insertion.

The authors (GS & FW) prefer the pre-formed stacked ePTFE blocks which are reduced and carved to shape for height, breadth and three-dimensional contour by the surgeon. For augmentation of the radix, a measured boat-shaped radix Gore-Tex graft is cut out of the block with a scalpel. The deep surface of the implant is then gouged out by diamond burring under cool irrigation.

The superficial lateral edges of the implant, that would form the brow-tip line, are contoured using the same diamond burr and cool irrigation. The deep lateral margin of the implant is similarly drilled and feathered thinly. This permits a seamless transition of the lateral implant surface to the lateral nasal bones upon which the implant sits; if this feathering is poorly done, a palpable step can be felt and/or seen several months later.

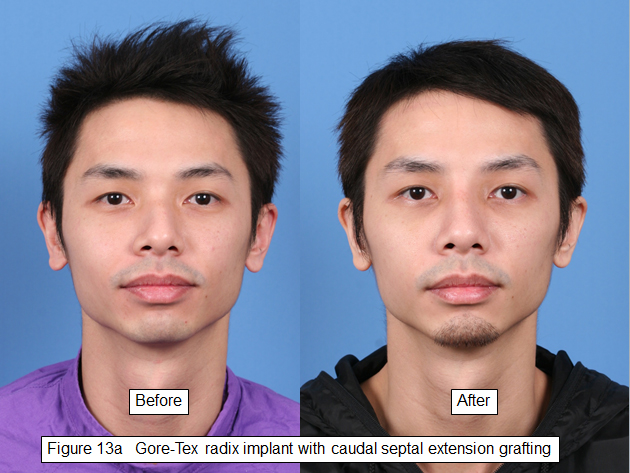

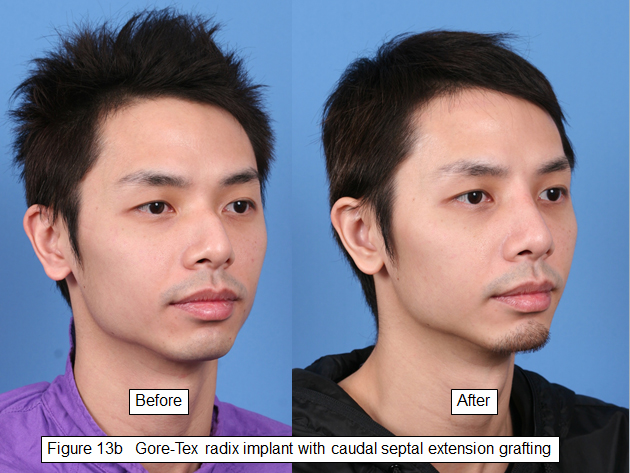

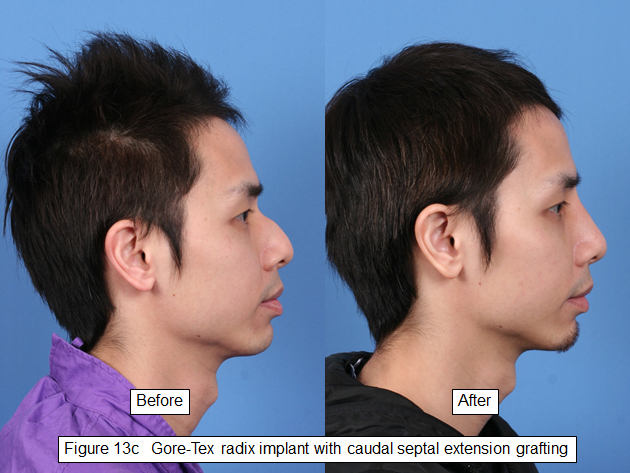

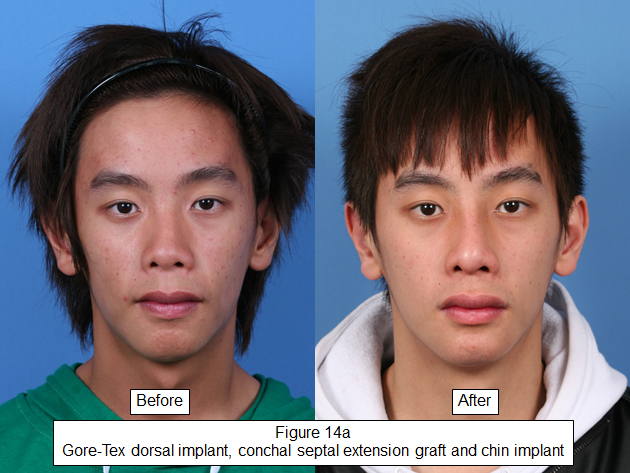

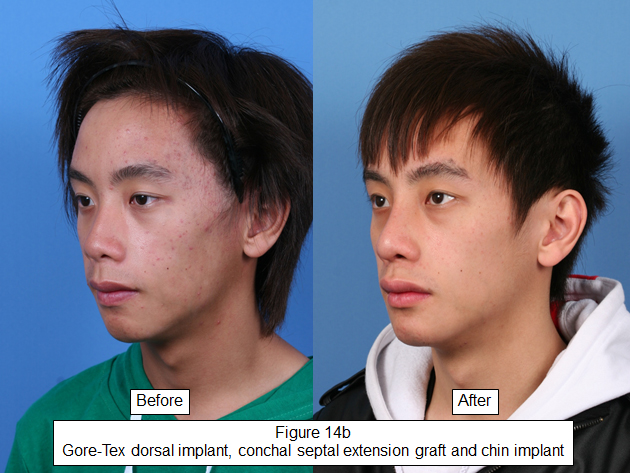

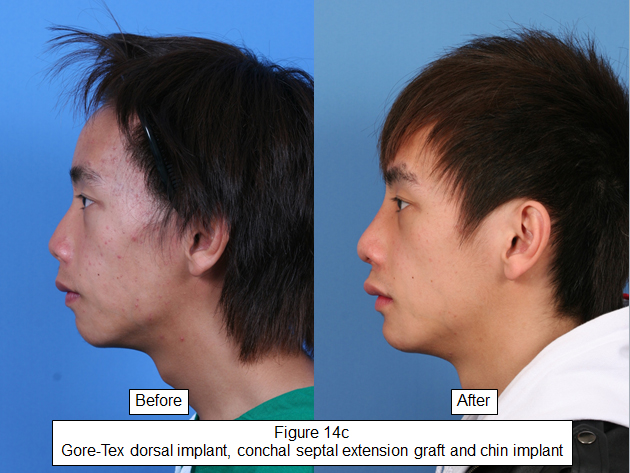

Finally the deep guttered surface of the Gore-Tex implant is scored to allow it to better conform to the bony concave curvature of the natural radix (see Figures 13 a-c). The finished implant is impregnated in an antibiotic-saline solution before insertion. It is placed in a subperiosteal pocket over the radix, and up toward the glabellar as the aesthetics require. Any subrhinion and supratip extension of the implant will sit supraperichondrially (see Figures 14 a-c). This camouflages any irregularities in this area with a relatively soft fill appearance.

The thinner ePTFE sheets can also be used for grafting in other areas of the nose. They can be cut to shape and used as cap grafts, shield grafts, supratip fills and alar base grafts. However our experience has shown that the use of these synthetic ePTFE grafts in mobile regions of the nose e.g. tip and alar, has a higher risk of associated graft complications of infection and extrusion.

The authors’ approach to Asian rhinoplasty

We prefer an autologous solution to achieve the rhinoplastic results wherever possible. This approach may incorporate the septum, conchal (see Figures 2a-c) and/or costal rib cartilages. If autologous rib cartilage is harvested, then there is usually sufficient cartilage to fulfill the rhinoplasty requirements for that patient.

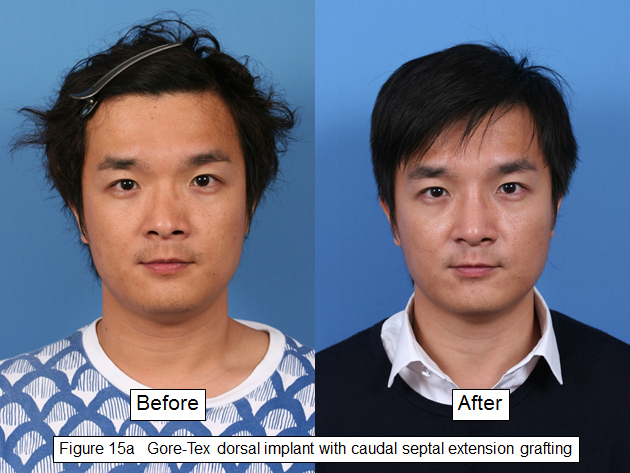

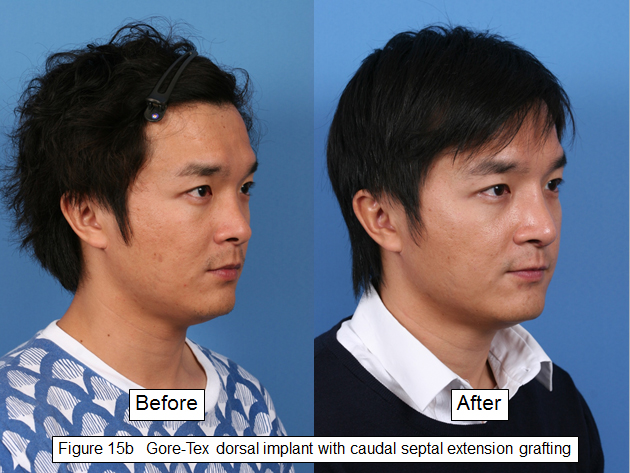

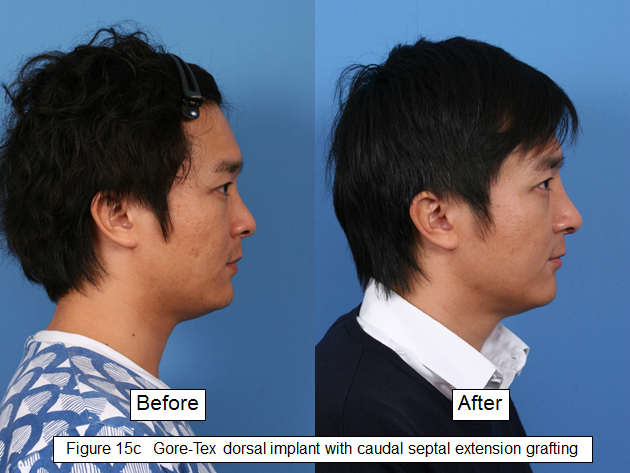

Some of our clients do not prefer the idea of an autologous rib harvest and solution. If dorsal augmentation is deemed necessary, we prefer to use sculptured Gore-Tex for the upper- third to two-thirds of the nose whilst septal and conchal cartilage grafts are preferred for caps and camouflaging of the lower two-thirds (see Figures 15 a-c and 16a-c).

The list below represents our alternative options for Asian rhinoplasty:

| Radix augmentation | autologous rib or sculptured Gore-Tex |

| Nasal dorsal mid-third | autologous rib / septum or sculptured Gore-Tex |

| Spreader graft | autologous rib / septum / concha |

| Caudal septal extension | autologous rib / septum / concha |

| (With/without polydiaxone foil reconstruction) | |

| Columella strut | septum / Medpor columella strut if stronger tip projection desired |

| Cap graft | septum / concha / secondary injectable |

| Shield graft | septum / concha |

| Lateral crural batten grafts | septum |

| Supratip graft | septum /concha / injectable filler |

| Rim grafts | septum / injectable filler |

Injectable solutions are offered as a primary option for the client who is unable or unwilling to undertake a formal surgical rhinoplasty. We would prefer to inject the reversible injectables as the initial treatment for all the reasons mentioned previously.

Injectables are also offered for minor touch ups after rhinoplasty as required. This would and should be discussed with the patient prior to the primary rhinoplasty surgery, as part of the informed consent process.

The nose in Chinese face reading philosophy

This subchapter highlights a very specific aspects of Asian rhinoplasty based on the ancient art of Chinese face reading. It is controversial from our own modern surgical perspective. However its teachings has been pervasive in Imperial China and her tribute kingdoms around her since the Tang Dynasty, and has been handed down through the elders over the ages. Its teachings also are practiced amongst modern face and fortune readers, and it remains in the consciousness or subconsciousness of some Asian clients. Hence some Asian clients seeking rhinoplastic surgery may request for certain rhinoplastic aspects with these teachings in mind.

Some clarity of the underlying concept of this art may help the surgeon to better understand their Asian clients’ appropriate or inappropriate expectation before surgery, and possibly their unhappiness with the results. It must be said that this ancient philosophy has not been scientifically tested according to current concepts of scientific testing. However perhaps it cannot be disregarded if one considers it as a large longitudinal, descriptive and observational study.

The nose

In Chinese face reading, our faces are divided into different parts (Chen XY). Our nose occupies the central part of our face. The nose’s implication in face reading is three-fold:

Ego

Our noses signify our self ego. We point to our noses when we want to draw people’s attention to ourselves. Hence a high nose in general means a high self esteem, and a low nose in general means a low self esteem.

Age significance

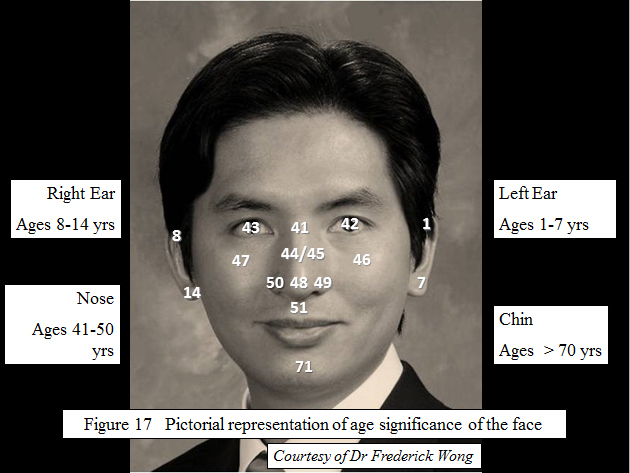

Our faces are divided into different parts (see Figures 17). Each part has its significance during the different ages of one’s life. The nose signifies our life period from 41 to 50 years. It starts from the radix (41), and ends at the nasal tip (48). Our left alar signifies our life at age 49 whilst our right alar signifies our life at 50. Hence defects in our noses can suggest problems during the corresponding times in our lives.

Life ‘palaces’

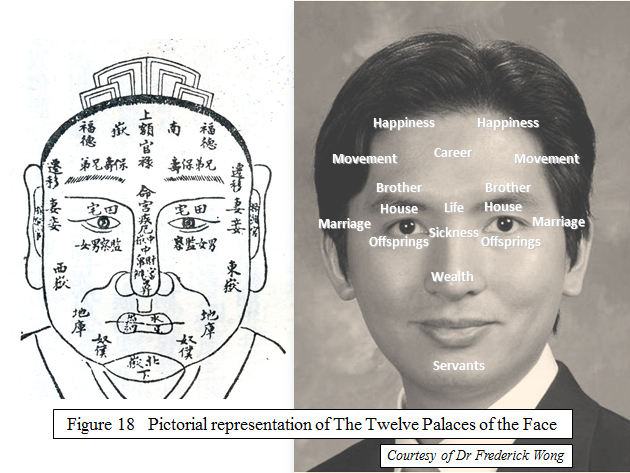

Our faces are also divided into different parts called the ‘Twelve Palaces’; each palace signifies different aspects of our lives (see Figures 18).

The radix is the ‘Life Palace’, signifying our luck and fame.

The rhinion is the ‘Sickness Palace’, which governs our health.

The nasal tip is the ‘Wealth Palace’, which governs our financial luck.

Face reading implications of the nose

From the above description, a person with a high nasal dorsum from the radix (Life Palace) all the way down to the tip is considered more likely to get famous. This is illustrated in the old Chinese saying, ‘Have a high nose and you will make your parents proud’.

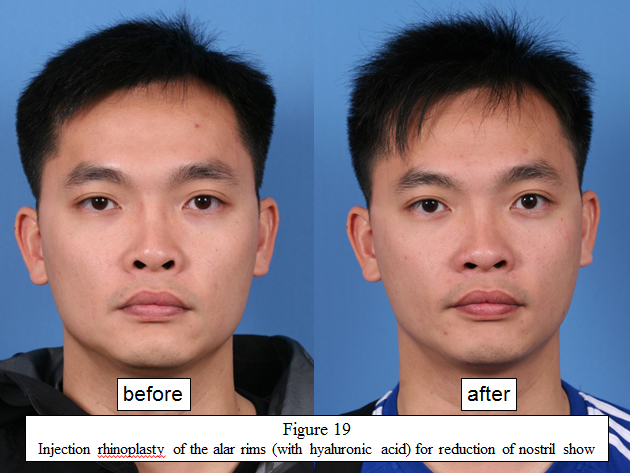

A strong and ‘fleshy’ nasal tip means a person will become rich, as the nasal tip is our ‘Wealth Palace’. This is especially true when that person also has minimal nostril show as the extent of the nostril show governs our money saving power.

With this negative nasal attribute, a person with too much nostril show (see Figure 19) is regarded as easily spending or losing the money he earns. Other negative nasal feature includes a hump over the nasal dorsum, which signifies a poorer health and relationship with other people (FTC Wong et al).

To put this philosophy into its proper perspective, we have to bear in mind that our faces should never be read part by part separately. Balance is a very important principle in all Chinese philosophies. A person with a good, high nose will only be successful if he or she also has other good facial features. Our, forehead, nose, right and left malar prominences, and chin are called ‘The Five Mountains’ on our faces. Their height and shape must be balanced for one to be qualified to have a ‘good face’.

This latter idea is perhaps much more easily comprehended nowadays by facial plastic surgeons when we discuss about the art of facial surgery, and achieving the balance and harmony of the beautiful face.

Conclusion

Asian nasal types do vary significantly. Asian rhinoplasty is conceptually about augmentation. A sound knowledge of available material options and singular / combination solutions is important when undertaking augmentative surgery for the Asian patient.

In finalizing the art of Asian rhinoplasty, the surgeon should also understand how to augment the nose whilst preserving the ethnic aesthetics of their Asian client. In some cases, they will also need to refine their sensitivities to better appreciate their Asian clients’ beliefs and cultural philosophy of the face and fortune.

References

Berghaus, A & Stelter, K. Alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty. Current opinions in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery. 2006; 14, p270-277

Toriumi, D & Pero, C. Asian Rhinoplasty. Clin Plastic Surg. 2010; 37, p335-352.

Daniel RK, Calvert JW. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 113:2156-2171

Romo T, Sclafani A, Sabini P. Use of porous high-density polyethylene in revision rhinoplasty and the platyrrhine nose. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1998; 22: p211-221

Pak MW, Chan ES, CA van Hasselt. Late complications of nasal augmentation using silicone implants. J Laryngol Otol1998; 112: p1074-1077

Tham et al. Silicone augmentation rhinoplasty in an Oriental population. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 2005; Vol 54, No 1.

Chen XY. The Full Textbook of Face Reading.

Frederick T C Wong, Gordon Soo, Ng Wai-pok Ng, CA van Hasselt, MCF Tong. Implication of Chinese Face Reading on the Aesthetic Sense. Archives of Facial Plastic Surgery. July 2010.

Legends

| Figure 1 | Graph showing differing Asian aesthetic preferences from Western standards |

| Figures 2 a, b, c | Septorhinoplasty with conchal radix and caudal septal extension graft |

| Figures 3 a, b, c | Injection rhinoplasty of the radix, tip and chin |

| Figures 4 a, b, c | Before and after NASHA filler of the dorsum |

| Figure 5 | Free and preformed silicone implants |

| Figure 6 | I shape implant |

| Figure 7 | L – shape silicone implant |

| Figure 8 | Carving of free-form silicone implant |

| Figure 9 | Primary fat graft rhinoplasty |

| Figure 10a | Stepwise or 2 Steps Rhinoplasty with autologous fat globules |

| Figure 10b | 2 Steps Rhinoplasty (with autologous fat & I-silicone implant) |

| Figure 11 | Silicone implant with impending tip extrusion, before and after fat grafting |

| Figure 12 | Strong tip projection with Medpor columella strut |

| Figure 13 a, b, c | Gore-Tex radix implant with caudal septal extension grafting |

| Figure 14 a, b, c | Gore-Tex dorsal implant, conchal septal extension graft and chin implant |

| Figure 15 a, b, c | Gore-Tex dorsal implant with caudal septal extension grafting (Male) |

| Figure 16 a, b, c | Gore-Tex dorsal implant and caudal septal extension grafting (Female) |

| Figure 17 | Pictorial representation of age significance of the face |

| Figure 18 | Pictorial representations of The Twelve Palaces of the Face |

| Figure 19 | Injection rhinoplasty of the alar rims (with hyaluronic acid) for reduction of nostril show |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Ng Wai-pok, Master of Face Reading Philosophy, for his input in this chapter.

Disclaimers

Dr Gordon Soo is the Chief of Facial Plastic Surgery and Clinical Associate Professor (honorary) of the Department of ORL, HNS, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is in private practice as a Director of The ENTific Centre, Hong Kong SAR. No conflict of interests declared.

Dr Frederick Wong is an Associate of Facial Plastic Surgery and Clinical Assistant Professor (honorary) of the Department of ORL, HNS, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is in private practice as a Director of The ENTific Centre, Hong Kong SAR. No conflict of interests declared.

Dr Choladhis Sinrachtanant is a Facial Plastic Surgeon and Senior Consultant of the Teeraporn Clinic, Bangkok, Thailand. He is the President of the Thailand Facial Plastic Surgery Society and Thailand representative of the ASEAN Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. No conflicts of interest declared.