Abstract

Rhinoplasty is one of the most common surgeries performed in the world, usually with cosmetics concerns. It is important to treat the nose as a functional unit, avoiding to separate aesthetics from function. The main goal in preservation Rhinoplasty techniques is to eliminate the dorsal hump while conserving the key stone area intact. This chapter would help to introduce the reader to one of the fist dorsal preservation techniques described in the earlies 90s called Let down using an endonasal approach which allows the visualization of the nasal septum and the osteocartilaginous pyramid.

Introduction

The nose should be considered as a functional unit, one of the elements of this concept being the form. We should never try to separate these two concepts, since form is function. Nasal structures should not be evaluated or handled in isolation from each other; any modification of one of the structures will have an impact on the rest of the elements, both functionally and aesthetically. If we perfectly understand the dynamic relationship of the components, we will be able to achieve more pleasant and natural results that are free of surgical stigma. If we adhere to the philosophy of preserving and repositioning tissues, we can achieve a balance between the correction of the nasal skeleton and the rest of the soft tissues that make up the nose, which we perceive as a 100% functional nose, in which function has not been sacrificed for the sake of form.

Background

Nasal surgery has been a common procedure since 1887-1891 when John Orland Roe performed the first elective nasal hump reduction. Many techniques had been published and modified to address a straight and more harmonious nasal dorsum, with a significant number of instrumentations to achieve hump removal.

In the early 1900’s were published dorsal preservation rhinoplasty techniques similar to what we are doing nowadays, However it isn’t until 1954 that Cottle described and published the rhinoplasty push down technique, the primary purpose was the conservation of an intact dorsum and create an effect of dorsal removal by pushing the dorsum down into the internal nose, this technique avoids nasal valve pathology and an open roof defect resulting from the hump removal and osteotomies described previously by Joseph. (1-4)

Nevertheless, the endonasal surgery techniques with Let Down technique was gradually abandoned in the major hospital otorhinolaryngology/head and neck surgery schools on account of the arrival of techniques such as external rhinoplasty due to the better visualization of the structures, thus enabling their direct modification, and Let Down fell into disuse; residents no longer learned the conventional closed (endonasal) rhinoplasty techniques, adhering to this new concept of teaching and visualization.

With the endonasal surgery techniques, the first assistant can see absolutely nothing, so the student must stand behind the instructor’s right shoulder in order to be able to see the surgery, learn the procedure and then be able to reproduce it.

As mention above the Push Down was described by Cottle in 1954. This technique differs radically from Joseph’s osteotomies described at the beginning of the past century, since it is focused on minimizing the trauma to the nasal dorsum, preserving the structures and preventing the collapse of the Upper lateral cartilages (ULC) with the closure of the valvular area. (5)

Cottle questioned about the complications that sometimes follow a hump removal and a concern of how much dorsum can be removed without interfering with nasal dorsum function. (6) To answer the first question, he pointed out important and not infrequent complications: the sinking of soft tissues into the open dorsum, that may be due to skin atrophy or contraction of scar tissue and vasomotor disturbances and allergy episodes following rhinoplasty. To answer the second question a common and well documented complication that should be avoid is the open roof syndrome that is characterized by local hypersensitivity, to prevent this, it is important to preserve the mucoperiosteum under the nasal bones and close the open roof resulting from the hump removal. (2)

Taking those concerns into account one of the most critical areas that should be handled with extreme care, is the Keystone area, which during Joseph’s traditional hump removal is amputated with the probable physiological repercussions it entails, as well as the aesthetic complications it provokes.

The most common ones reported are excessive osseous or osteocartilaginous resection leading to a saddle nose or open roof syndrome, insufficient cartilaginous resection, or “polly beak” supratip deformity, the inverted “V” deformity, valvular pinching and collapse, osseous rocker deformity, and deviation of the osteocartilaginous nasal pyramid. (Fig. 1) Also it’s practically impossible to align the nasal pyramid with asymmetric Joseph osteotomies.

Various procedures have been described for the management of these aesthetic-functional sequelae caused by the afore-mentioned technique, such as the primary use of spreader grafts (7) that, on the one hand are difficult to position with an endonasal approach, which causes us to do an external rhinoplasty with an extended septal approach to obtain these grafts, thus resolving the basic problem, which is the nasal septum.

However, the push down technique has its technical limitations, because when it is done the traditional way, the osseous pyramid within the nasal cavity is pushed, limiting the degree to which we can decrease the nasal

hump as we would like, because the inward displacement of the osseous fragment is restricted by the lower turbinate and provokes a narrowing of the airway, thus the push down is not suitable for humps larger than 5mm. Cottle’s students, Vernon Gray and Huizing, noticed that and in 1975 they modified Cottle’s original technique by making a resection of triangular bony wedges from the maxillary ramus, allowing the pyramid to descend freely into the space leaved by this wedges, without obstructing the pyriform aperture, nor the cartilaginous angles, describing what we know as the Let Down technique. (1-4, 8,9)

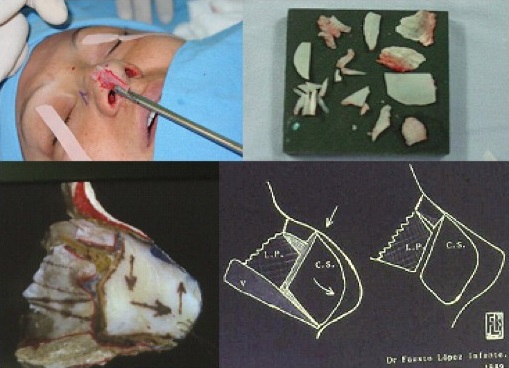

Furthermore, in the early 90s Fausto López- Infante proposed a modification in the let down technique to treat the twisted nose, by resection of a single wedge of bone on the elongated side of the asymmetric nasal pyramid and then a baseline osteotomy on the contralateral side and a transverse osteotomy are done to mobilize the whole osteocartilaginous pyramid, thus correcting the asymmetry by obtaining both nasal bones with the same length. (10)

The key to a successful rhinoseptoplasty lies in the septum; aligning it, relaxing the coronal and axial tension, allows us to provide the nose with a central stability. If we only resect the dorsal border, believing that the septum is practically straight, without considering the tension it provides, when we free it from above, it will tend to push outward, diverting the cartilaginous dorsum. This is why it was believed that the nose goes where the septum goes. The truth is that there had not been a good integral evaluation of the structures, therefore, no diagnosis, which is why the results subsequent to the healing of the tissues were so poor functionally and aesthetically.

Nowadays, we have realized the consequences of hump removal disturbing the K-area, while a dorsal preservation rhinoplasty can be performed in which the dorsum anatomy is conserved.

Let Down technique preserves the dorsum and the normal relation between the osseous dome, the cartilaginous dome, and the lobule, corrects the primary pathology, which resides in the septum, relaxing the nasal tension as well. It is not technically difficult, as it might be imagined. It only requires an understanding of the direction in which structures move and the effect of this displacement.

Clinical Findings

A complete evaluation of the face and nose is primordial, the basis of success in rhinology is the diagnosis. The evaluation should include preoperative photographs, nasal computed tomography (CT) and a complete clinical examination.

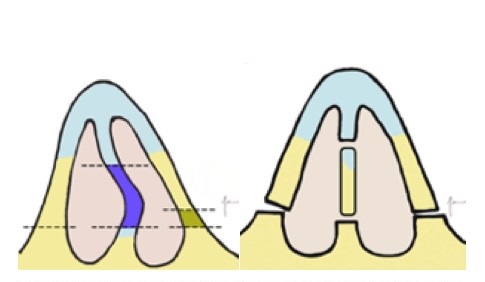

We begin by inspection, paying special attention to the nasal pyramid, both osseous and cartilaginous, determining whether it is centered on the median line, if it is high and tense, or if there is any right or left deviation, and if there is any osseous or osteocartilaginous compromise (Fig. 2). We evaluate the relation of the ULC and the Lower Lateral Cartilages (LLC) to the septal cartilage, taking into consideration that the presence of pathology of the septal cartilage creates asymmetry and deviation of the cartilaginous pyramid. Once we have identified the pathology and arrived at an integrated diagnosis we can design a plan to correct it.

Surgical Technique

The Let Down maneuver can only be achieved through adequate septal work, which we carry out in the following manner: Infiltration is done with lidocaine 2% and epinephrine (1:100,000) in the nasion, intercartilaginous area, piriform aperture, membranous septum, and hemitransfixion site bilaterally.

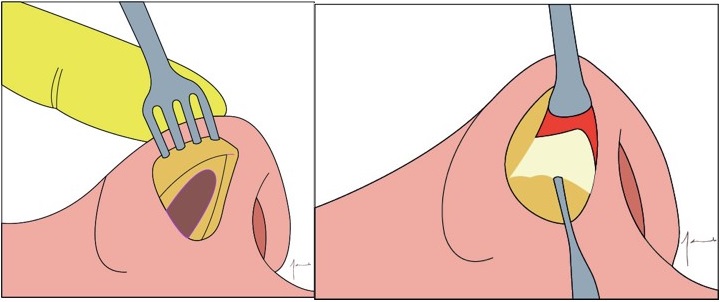

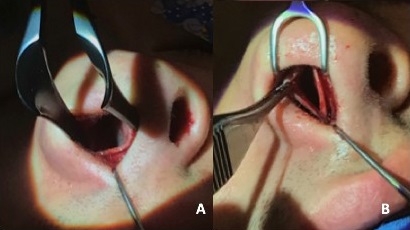

The senior author uses an integral approach for endonasal surgery, which is a combination of bilateral intercartilaginous incisions joined in a “T” to the hemitransfixion incision and a subsequent “M” plasty avoiding the complications of the original Joseph incision, and allowing the visualization of the nasal septum and the osteocartilaginous pyramid. (11) (Fig. 3)

This leaves the nasal tip complex free and we achieve an extended exposure which allows us to visualize the entire cartilaginous dorsum and the caudal edge of the septal cartilage in order to begin the subperichondrial dissection and complete the maxillary-premaxillary approach thoroughly described by Cottle completely exposing the septum, from the anterior nasal spine, its ventral border, following the posterior border to its relation with the ULC, and deep and posteriorly, its articulation with the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid.

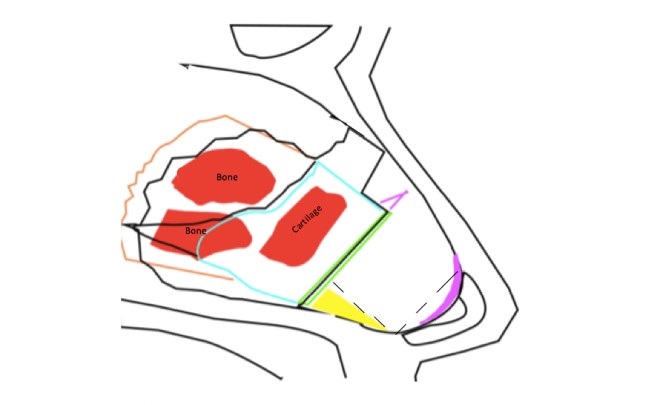

Once the dissection has been completed, and with a direct view, the septal cartilage is incised with an angled Beaver knife or with an angled ophthalmological Crescent blade, perpendicularly to the caudal edge of the septum, for about 2 cm. To insert the Ballanger knife and incise an extended fragment of cartilage, which we will keep for anatomical replacement and for grafting if it proves necessary. Viewing the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid, and the vomer, we cut directly to remove the osseous pathology. Once a ventral space is formed, the osteocartilaginous septum can be displaced downward to achieve the descent of the nasal pyramid. Again, the septum is the key to the Let Down. By releasing the ventral border and dissecting a ventral strip, we can adjust the level of the nasal dorsum, fixing the septal cartilage to the anterior nasal spine with a figure 8 stitch (pds 3-0). If necessary a vertical caudal strip can be removed as well as a small triangle anterior the the junction between the perpendicular laminae and the septal cartilage. (Fig. 4 -5 )

This septoplasty is aggressive and not at all conservative. The amount of septum dissected is not significant, as has been described in articles as extra corporeal septoplasty, provided that an anatomical replacement of the aligned osseous and cartilaginous fragments is done. (Fig. 6) In every instance these will be anchored with trans-septal stitches with simple 4-0 catgut.

Green: Septal cartilague first incision

Blue: Resection of septal cartilage with Ballenger

Orange: Resection of perpendicular plate

Yellow: Ventral strip

Purple: Vertical caudal strip and small triangle anterior the perpendicular laminae and septal cartilague

Let Down and Alignment of the Nasal Pyramid

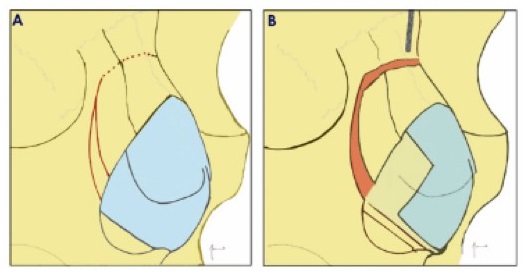

This is achieved by means of a 4 mm bilateral vestibular incision that can be done in one of two ways: a) with the help of a monopolar cautery and a Colorado tip we cut directly until we can see the anterior border of the ascending ramus, b) with the scalpel we make an incision in the mucosa (a superficial incision) and with iris scissors we dissect without cutting the muscles until we can identify the border of the ascending ramus on the lateral part of the piriform aperture. These two options avoid the bleeding that would be caused by cutting directly into the muscle and periosteum, significantly decreasing the postoperative edema and ecchymosis. With the Cottle dissector an internal subperiostic tunnel is made, approximately 5 mm in length, and an external tunnel, following the facial plane to the union of the ascending ramus with the nasal bones along the length of the lateral osteotomy, considering the width of the wedge that will be removed. To carry out the osteotomies with a chisel, we can use a curved 3 mm Cook chisel (with a single lateral guard) or a 2 mm double guard curved chisel (López-Infante chisel), doing the lateral superior osteotomy first (parallel to the facial plane), which would correspond to the upper portion of the wedge, insert the chisel so that the second lateral osteotomy continues at the level of the facial plane and joins the superior osteotomy approximately 1 to 1.5 m above, depending on the length of the maxillary ascending ramus and the amount of lowering we desire, this wedge can also be excise with rongeur forceps in a single step, completing the osteotomy upwards later, with the chisel. (Fig.7)

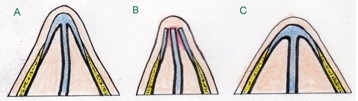

If the pyramid is symmetrical and tall, then the traditional let down is done bilaterally. If the pyramid is deviated, for example to the left, we would do a double osteotomy on the right side with resection of the osseus wedge fragment or a bigger wedge on the deviated side (longer side), which will allow the pyramid to fall toward that right, and on the left bone a smaller wedge or only a lateral conventional osteotomy will be performed. (Fig. 8)

Once the lateral osteotomies are completed, we release the nasal pyramid by means of a percutaneous transverse osteotomy with a 2mm chisel, either in greenstick (which will work as a hinge, and height will not be lost in that area) or complete, which would allow us to mobilize the osseous nasal pyramid as a block, as a unit, toward the midline and downward. (Fig.9)

This combination of osteotomies, plus the septal work gives us the freedom to handle and relocate the entire nasal pyramid without modifying the structure and integrity of the dorsum, basing its height on the relocation of the septum as described above, preserving and enhancing the anatomical relations of the dorsum, thus avoiding the complications produced by the trauma and the destruction caused by other techniques. The degree of downward displacement is directly related to the width of the osseous wedge resected and to the height that is determined when anchoring the septum to the anterior nasal spine.

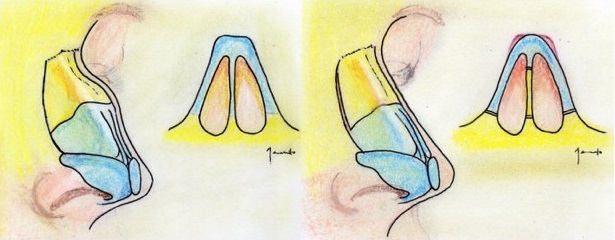

This displacement modifies the naso-facial structures in the following way

1.- In the area of the nasal bones we preserve a house-shaped structure with its roof and walls intact on both sides, thus maintaining the width of the dorsum intact, which, if partial remodeling is required, it can be done by using a Maltz rasp or scalpel, but preserving the natural layers, and keeping the intranasal space isolated from the subcutaneous cellular tissue and the skin. Even when that pyramid has been freed and is movable, it can be gently filed down, holding it firmly between the thumb and index fingers of the surgeon’s left hand. This procedure also preserves the junction of the nasal bones with the ULC, thus avoiding their separation and collapse, preventing the pinching and formation of an inverted V. (Fig.10)

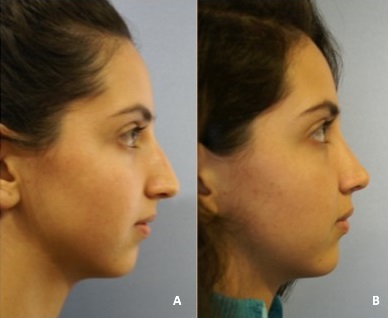

2.- It has an effect upon the soft tissues of the lateral nasal wall, due to the fact that we use this technique in patients who generally have a high nose with tension and poor development of the middle third of the face. Upon resecting the osseous wedges and decreasing the distance or total height of the nose, the soft tissues of the nose (nasal SMAS) migrate downward, creating a volumetric increase at the naso-facial base, and the inferior orbital rim, compensating for this poor development of the middle third, thus harmonizing the general facial appearance. (Fig. 11, 12)

3.- Without modifying the nasal base, the relation of the nasal septum and lateral walls improves, because with an excessive projection, the angle is acute, and with a poor projection or platyrrhinal nose, the angle is obtuse, thus affecting nasal flow. With a normal nasal projection, the angle formed by the septum and the nose becomes normal. With the Let Down we modify the angle of the valve, the width of the airway, and we decrease the dorsum without changing other structures and compromising function. (Fig. 13)

Complications

Let down is a noble technique once a good learning curve has been achieved; however, like in any surgery, we can face complications.

An insufficient descent of the hump would be the number one complication of this Let Down technique. This is due to an inadequate or insufficient septal management, creating internal resistance to the achievement of the desired degree of displacement, or to an insufficient resection of the ascending ramus of the maxillary. This would stand in the way of an adequate overlapping of the osseous fragments, or the wedge may not have been completed all the way to the cephalic end of the osteotomy, and can limit the inferior movement of the nasal pyramid.

Other problems that occur in lateral osteotomies are irregularities in the trace and visible staggering of the fragments, which can be avoided by verifying that the incision is precisely on the facial plane when cutting, lowering the trace as much as possible. This will keep it from being perceptible and keep the fragments from resting in an aligned position. (12)

In the septum, we can find as complication in the first place, deformity or residual deviation. This can be avoided by doing an extended resection, taking into consideration the coronal and the axial planes, repositioning the osteo-cartilaginous fragments after working with them, aligning them as much as possible and anchoring them with trans-septal sutures, which should not be tightened, and should follow the vascularity pattern and the fixation of the caudal edge of the septal cartilage to the anterior spine.

Postoperative Care

Following the principles of general surgery, in the area of osteotomies a Penrose surgical drain is placed through the vestibular incision. (Fig. 14) It will remain in place for 48 hours. A bilateral anterior nasal packing is used with ½ Telfa, which will also be removed after 48 hours.

We apply an external big nasal dressing with Micropore and an Aquaplast cast. This dressing will remain in place for 7 days, then removed entirely and replaced by a small nasal dressing of Micropore for another 10 days. (Fig. 15)

It is important to clearly instruct the patient regarding his sleeping position, which will be strictly semi-Fowler with the head facing forward. There should be no physical strain. A cold mask should be applied intermittently in addition to the rest of the conventional care that all surgeons use, including routine analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antibiotic medication.

Conclusions

Although let down technique needs a learning curve, once it is learned and executed correctly the results are very satisfactory aesthetically speaking and it maintains nasal function. Like Saban mentioned in his work, any dorsal preservation technique should be part of the repertoire of a rhinoplasty surgeon, in some cases it would be preferable to use a dorsal preservation technique rather than the other conventional techniques to approach the nasal dorsum.(13)

An adequate septal work is essential when performing a let down surgery. It can be applied to any septal pathology, unlike Saban’s technique which is not a technique of choice in ventral septal pathologies.

With this technique we can achieve a straight or even concave nasal dorsum without worrying about the complications that a wide hump removal can cause, obtaining natural results free of surgical stigma.

Disclosures

The authors declared no conflicts of interests or financial interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Bibliography

- Neves Pinto, RM. On the “let-down” procedure in septorhinoplasty. Rhinology. 1997; 35:178-180.

- Halewyck S, Michel O, Daele J, et. al. A review of nasal dorsal hump reduction techniques, with a particular emphasis on a comparison of component and composite removal. B-ENT. 2010; 6: 41-48.

- Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR, Janis JE. Component Dorsal Hump Reduction: The Importance of Maintaining Dorsal Aesthetic Lines in Rhinoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004; 114 (5): 1298-1308.

- Kienstra MA, Sherris DA, Kern EB. Osteotomy and pyramid modification in the Joseph and Cottle rhinoplasty. Functional Reconstructive Surgery. 1999; 7 (3): 279-294.

- Rollin K. Daniel; Rinoplastía. Grabb And Smith’s Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Sixth Edition 2002. Chapter 53, Lippincot and Raven.

- Cottle MH. Nasal roof repair and hump removal. AMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1954;60 (4): 408-414.

- Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984 Feb; 73 (2): 230-9.

- Huizing EH. Push-down of the external nasal pyramid by resection of wedges. Paper presented at the 6th congress of the European Rhinologic Society.1975: 185- 190.

- Pirsig W, Königs D. Wedge resection in rhinosurgery: A review of the literature and long-term results in a hundred cases. Rhinology. 1988; 26: 77-88.

- Kern EB. Commentary on: Dorsal preservation: The Push Down Technique reassessed. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2018; 38: 132.

- López Ulloa F. Abordaje integral de Fausto López Infante para cirugía endonasal. Anales de Otorrinolaringología Mexicana. 2016; 61(4):271-279.

- Holt GR, Garner ET, McLarey D. Postoperative sequelae and complications of rhinoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1987 Nov;20(4):853-76.

- Saban Y, Daniel RK, Polselli R, et. al. Dorsal preservation: The Push Down technique reassessed. Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2018; 1-15.