The Overprojected Nasal Dorsum

Introduction

The nasal dorsum plays an important role in the aesthetic evaluation of the nose and the face as a whole. The upper two thirds of the nose is formed by the bony and cartilaginous dorsum. This chapter will attribute to the overprojected nasal dorsum both the bony and cartilaginous part, its anatomy and the aesthetic analysis. The surgical approaches and techniques of a dorsal hump reduction and osteotomies of the nasal bony pyramid will be presented and possible complications will be discussed.

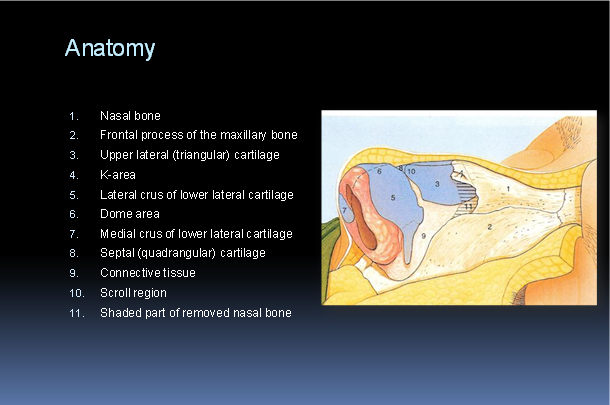

Anatomy

The nasal dorsum consists of a bony and cartilaginous dorsum. The bony part, also called the bony nasal pyramid, is made up by the paired nasal bones. Cranially these bones form the nasofrontal angle at the junction with the nasal process of the frontal bone. Laterally they articulate with the frontal process of the maxillary bone at the nasomaxillary suture. The cartilaginous part of the dorsum is made up by the cartilaginous septum that forms one unit with the upper laterals (triangular cartilages). Therefore, surgery on the nasal dorsum will affect both the medial side of the triangular cartilages as well as the cartilaginous nasal septum. The triangular cartilages insert under the nasal bones like a rooftile and in this way form an important support mechanism for the nasal dorsum. This overlapping area is called the K-area (keystone area) and has to be respected during surgery. The bony and cartilaginous skeleton is covered by the skin and subcutaneous tissue, together with a connective tissue layer which envelopes the musculature.

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 1, with permission)

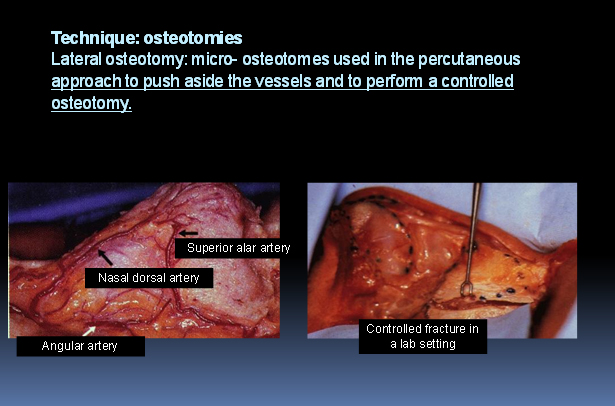

This layer of connective tissue and the muscles of the nose can be seen as an extension of the facial superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS). There’s a variation in the thickness of the skin/soft-tissue envelope (SSTE) from patient to patient, as well as from region to region. It is usually thicker in the supratip and nasal frontal angle region (1) (Fig.1). The blood supply to the external nose and dorsum is provided by branches of the facial artery, which divides into the labial, alar and angular artery, and the ophthalmic artery. The angular artery supplies the dorsum and runs laterally along the bony and cartilaginous part of it. All the vessels, both venous and arterial are running in and underneath the SMAS layer. When surgery of the phrame-work of the nasal dorsum has to be performed, one should dissect in an avascular thin multilayered sliding plane close to the perichondrium. This is the layer which gives mobility to the SSTE and can easily be detected during surgery.

Aesthetic analysis

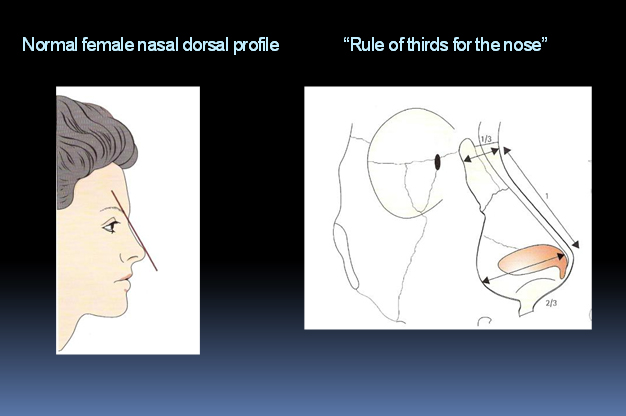

The lateral or profile view is the best to analyse the nasal dorsum. The cartilaginous dorsum ends just cranially from the nasal tip in a slight supratip depression (supratip break). There’s a difference between the normal configuration of the aesthetically pleasing profile view of the dorsum for females and for males. If you draw a straight line drawn from nasion to the tip defining point of the nose, the aesthetic dorsal profile for females, including supratip, is defined as a line lying ± 2 mm deep from this straight line. The male nasal dorsal profile is acceptable when it is in one straight line with the tip of the nose (Fig. 2). The height and length of the nasal dorsum is closely related with the position of nasal tip and nasal frontal angle. This is defined by a “rule of thirds” where the height of the nasal frontal angle, the projection of the nasal tip and the length of the nasal dorsum are related in a rate of 1/3 to 2/3 to 3/3 (Fig. 2).

(From Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Nasal Dorsal Management. In: Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Hodder Arnold, London, 2006. Chapter 19, reproduced by permission of Hodder education.)

(From Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Nasal Dorsal Management. In: Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Hodder Arnold, London, 2006. Chapter 19, reproduced by permission of Hodder education.)

The height of the nasal vault can be measured from the medial canthus, or from the maxillary-facial surface. There are also racial differences in the height of the nose. The Caucasian nose is more pronounced than the negroid and asian nose which is more flat and less projected. The nasofrontal angle varies between 115-130 degrees and is formed by lines parallel to the forehead and nasal dorsum, crossing at the nasion and also varies greatly amongst individuals (2).

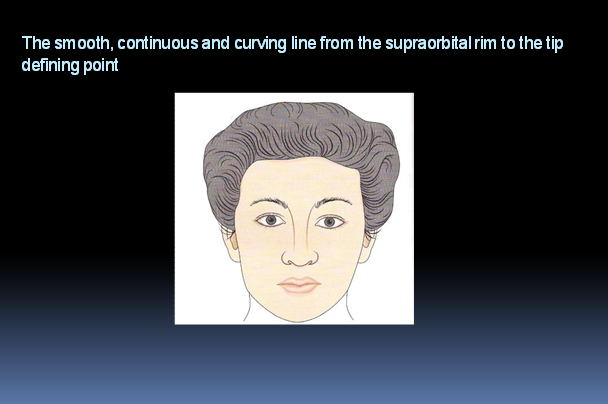

The oblique view or ¾ view gives a good overall impression of the contours of the lateral nasal wall. It is therefore very helpful in evaluating shape and width of the bony and cartilaginous nasal pyramid. Especially the line running from the supraorbital rim, along the lateral border of the nasal dorsum, towards the tip should be smoothly curving in females (Fig. 3). In males it may show additional curving as the result of a small hump. As previously mentioned the height and width of the nasal dorsum are closely related. A lower dorsum does suggest a relatively wide nasal bridge and vice versa.

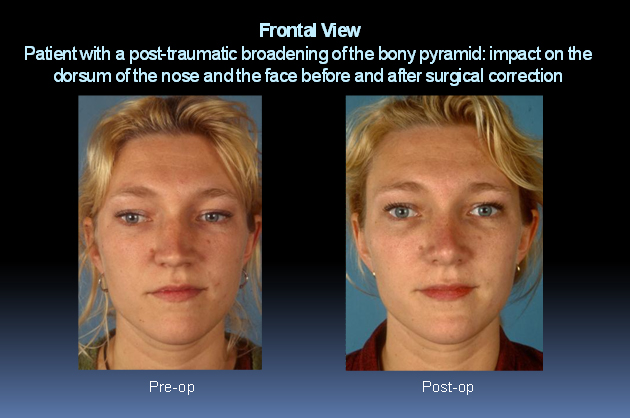

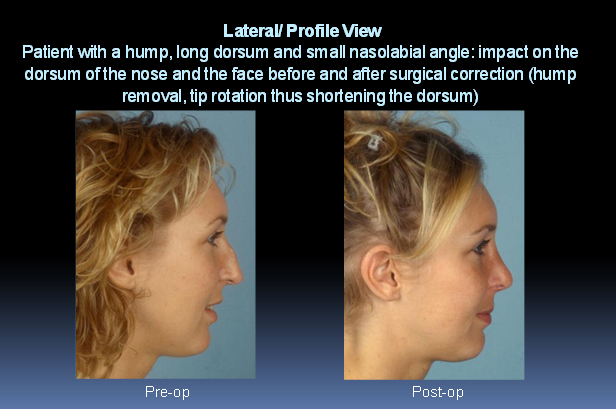

In a frontal or anteroposterior view a good overall assessment of the length and width of the nose in relation to other facial characteristics is possible. The length of the nasal dorsum depends largely on the height of the middle one third of the face and on tip rotation. The more the tip is rotated, the shorter the dorsum (Fig. 4) (2). This can be seen in the patient shown in Fig. 4 and also in a profile view in the patient in Fig. 5.

Finally, the superior view is not part of the standard series in documentation, but gives a good evaluation of the width of the dorsal bridge, and eventual deviations of the pyramid can easily be seen.

(From Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Nasal Dorsal Management. In: Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Hodder Arnold, London, 2006. Chapter 19, reproduced by permission of Hodder education.)

(From Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Nasal Dorsal Management. In: Vuyk, H.D., Lohuis, P.J.F.M. Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Hodder Arnold, London, 2006. Chapter 19, reproduced by permission of Hodder education.)

Dorsal hump reduction

Introduction

The removal of a hump is a frequent procedure in rhinoplasty. Its etiology is usually congenital or familial, although a nasal hump can also be the result of trauma with dislocation of the nasal bones and/or callus formation.

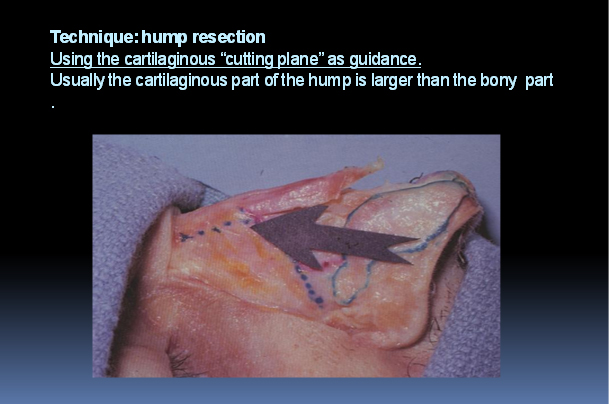

As has been previously outlined the nasal dorsum consists of a bony part and a cartilaginous part. The overprojection can be in the upper third (= bony pyramid); middle third (= cartilaginous pyramid) or it might be a combination of both. Usually the bony part of the hump is smaller than the cartilaginous part. Depending on the individual anatomy, surgery needs to deal with the nasal bones, septum, and upper laterals, and one has to correct the part that is overprojected. Most often the overprojected nasal dorsum is a combination of an overprojected bony and cartilaginous dorsum.

The overprojection of the dorsum can be “absolute” or “relative” and it’s important to differentiate between these two. The bony nasal dorsum might be relatively overprojected in case of an acutenasofrontal angle or when the cartilaginous dorsum has lost its support. Instead of reducing the dorsum, as you should in case of an absolute overprojection, relative overprojection often requires some degree of augmentation.

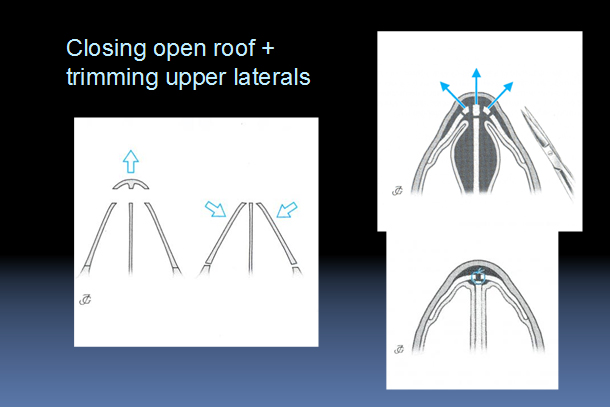

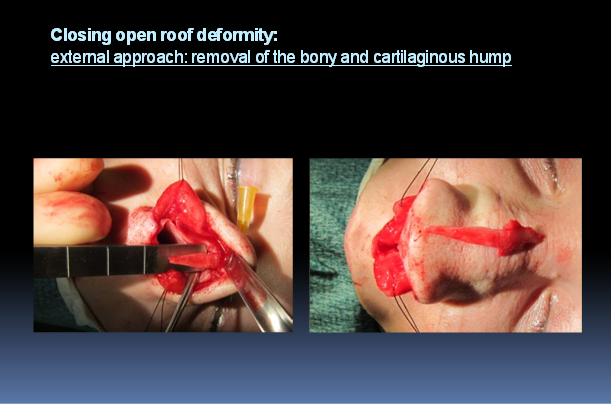

A dorsal hump reduction will most often lead to a so called “open roof”. Apart from being unaesthetic this might also cause pain because of contact of the mucosa with the overlying skin. In most of the cases the “open roof” has to be closed by performing nasal osteotomies, which will be discussed later (Fig. 6). In case of a small “open roof” deformity it’s also an option to close it by putting some cartilage, obtained while reducing the hump, back on top of the dorsum. This is one of the reasons one should never throw away any cartilage or bone from the patient derived during surgery until final closure of all wounds, because you might need it for re-usage. An open roof might also be closed with spreader grafts.

(From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

Surgical approaches and techniques

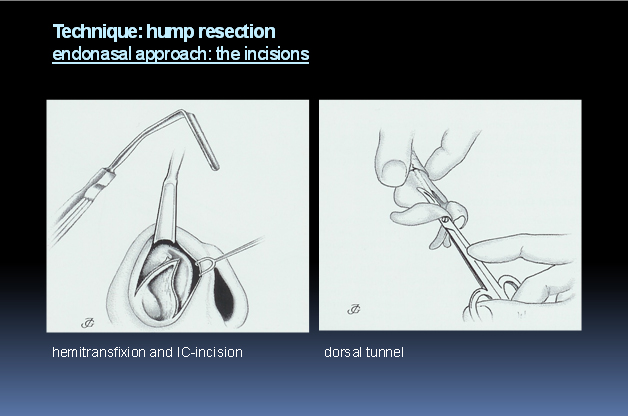

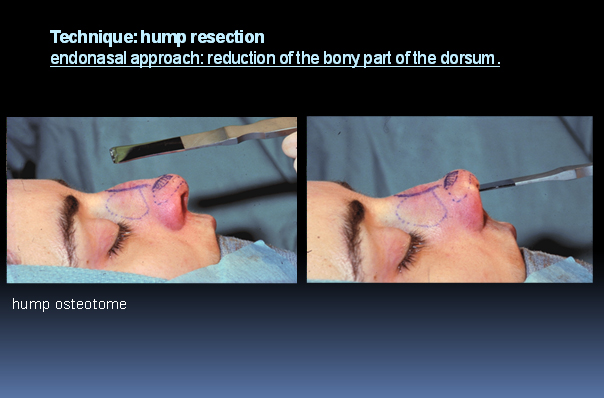

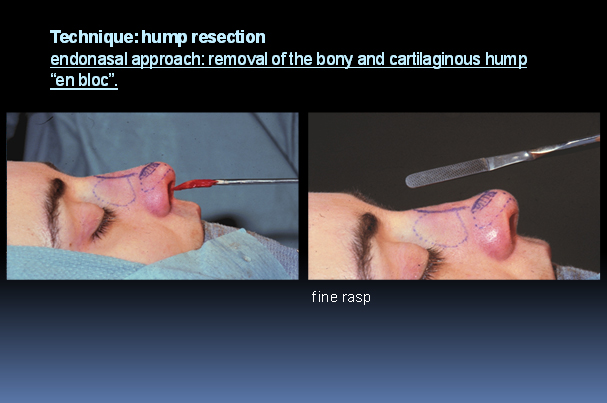

The two approaches for the bony and cartilaginous dorsum are the endonasal and external way referring to the design of the incisions. In the endonasal approach, all incisions are placed inside the nose: when intercartilaginous incisions (IC) are connected with the hemitransfixion incision maximal access to the nasal dorsum is obtained (Fig. 7). The external approach combines a midcollumellar incision with two infracartilaginous incisions. First we will discuss the general technique of the hump reduction and thereafter some of the technical aspects of both approaches will be compared.

In case of an endonasal approach the intercartilaginous incision is located just caudal of the nasal valve, running from lateral to medial around the anterior septal angle. Careful dissection between the upper and lower lateral cartilage is important to prevent postoperative irregularities of the lateral nasal wall (Fig. 7).

(From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

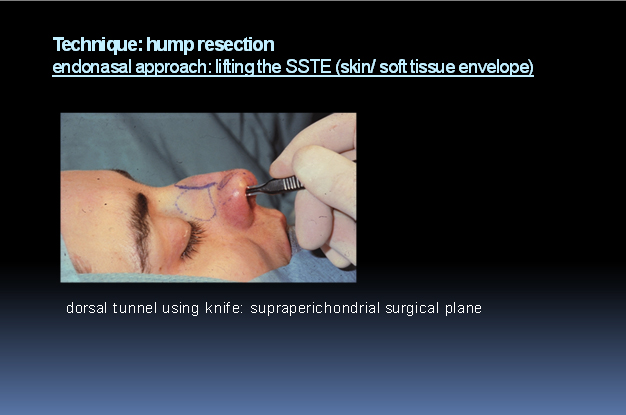

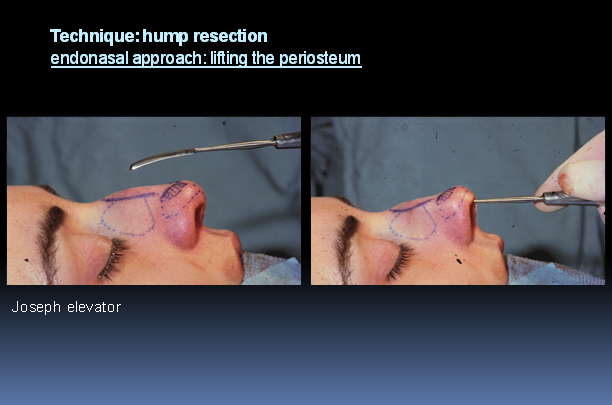

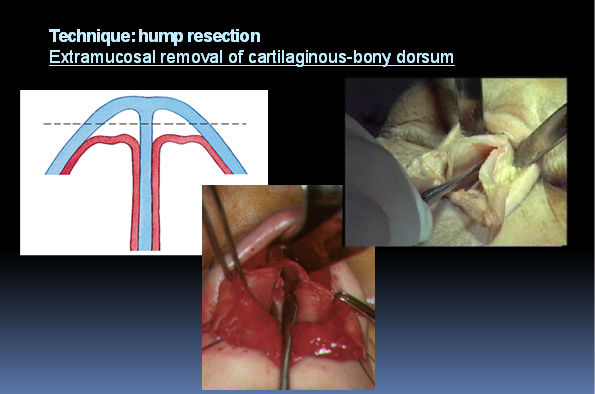

The cartilaginous part of the hump is exposed by lifting of the skin/soft-tissue envelope (SSTE) thus making a dorsal tunnel. This is performed in a supraperichondrial surgical plane by making small circular movements with the knife. By leaving the perichondrium on the nasal dorsum and the upper lateral cartilages, and staying underneath the nasal muscles, unnecessary bleeding and scarring is prevented. In this way tearing of small vessels (which will contract and trombose much faster), as you would do when using scissors, is avoided (Fig. 8).

At this point it’s important to remember that the thickness of the skin differs along the nasal dorsum. A little thicker over the domes and the supratip area, thin over the cartilaginous nasal dorsum and the nasal bones, and a little thicker again in the glabella region (Fig. 1). Make sure you do not perforate the skin in this region.

After preparing the cartilaginous part of the hump a transition is made to the subperiosteal plane to expose the bony part (upper third). An incision is made in the periosteum at the caudal side of the nasal bone, not extending too far laterally. The periosteum together with the SSTE can then be bluntly elevated towards the glabellar region for example with a Joseph elevator (Fig. 9). In this way all soft tissues are lifted off the bony and cartilaginous dorsum resulting in a clear view that will allow a number of procedures for correction of the nasal dorsum. Make sure not to go underneath the nasal bone and destroy the attachment with the upper lateral cartilage (K-area), as this will undermine the support of the nasal dorsum.

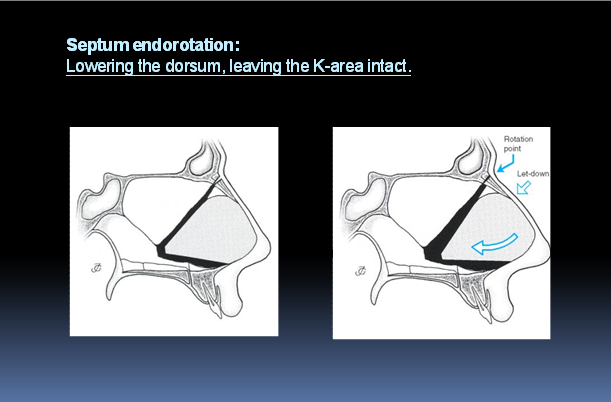

If the septum has to be corrected as well, this should be done before reduction of the dorsum. When performing a posterior chondrotomy (situated at the junction between the quadrangular cartilage and the perpendicular plate) at least one centimeter should be left intact at the dorsal-cephalic end of the cartilage. This is once again an attempt to leave the K-area undisturbed because changing the structure and tension of the septum can cause dramatic changes in the nasal vault. After removing an inferior strip of the septum the dorsum can be lowered by pivoting the septal cartilage downwards and posteriorly (Fig.10). The septum must be stabilized on the anterior nasal spine after which you can proceed with the hump reduction.

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

(From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

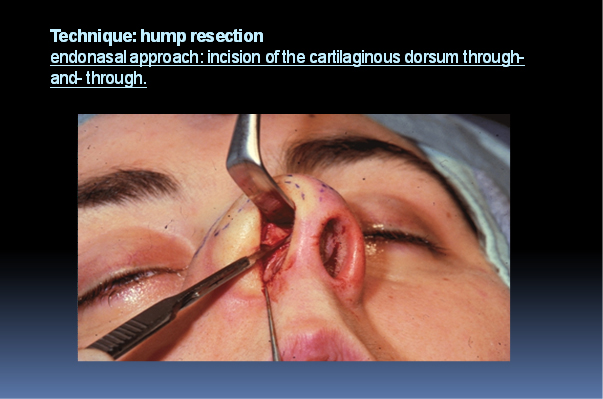

An IC incision can be extended into a hemitransfixion in order to increase the exposure. The hump reduction starts with lowering the cartilaginous part, if indicated, sharply with a knife. The dorsal septum and both the upper laterals can be cut in one through-and-through incision, up to the nasal bones (Fig. 11). It’s important to work symmetrical cutting through three layers (= both upper laterals and septum).

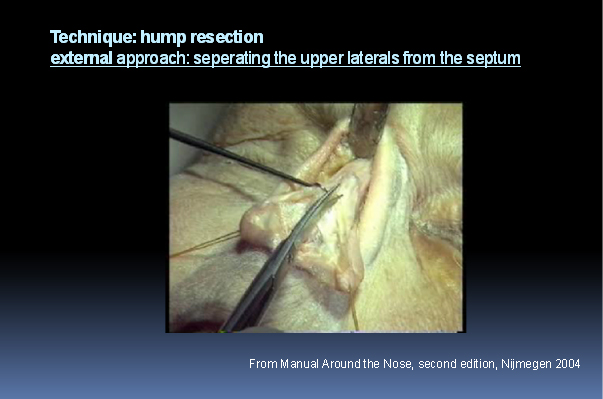

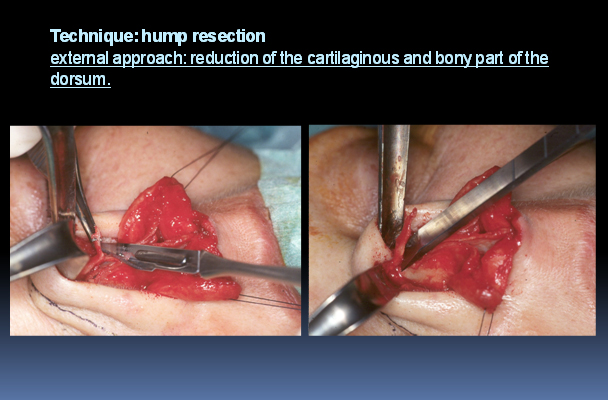

Another method is to reduce the cartilaginous part in three steps. First of all the upper laterals are dissected on both sides of the septum which is easier in an external approach (Fig. 12, Movie 1). Then the septal dorsal cartilage is lowered to the desired height and subsequently, if necessary, the upper laterals are trimmed one by one. Take into account that the upper lateral cartilages, which are connected to the nasal bones, may come downward when you perform osteotomies.

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

There are several techniques to reduce the height of the bony dorsum. In case of a small hump, a rasp or powered instrumentation can be used to get the desired reduction. This kind of bony hump reduction usually gives a rather smooth contour of the bony pyramid. Care should be taken not to tear or damage the periosteum by the oscillating movements of the instruments. Large bony humps are best reduced with a broad flat osteotome that cuts through both nasal bones (and septum) at once. The osteotome is introduced in the already made “cutting plane” of the cartilaginous hump (Fig 13, 14, 15). In this way the osseocartilaginous hump can be removed “en bloc”. Rough edges can be rounded of with a rasp (Fig. 16). It is advisable to push down the mucoperichondrium underneath the nasal bones and upper laterals. In this way unnecessary haematoma and oedema can be avoided as osteotomies are performed outside the mucosa (Fig. 17, Movie 2). Additional wedges of bone can be removed with a burr or micro-osteotomes if the width of the dorsum needs to be made narrower.

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

(Adapted from Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

After the hump has been removed it’s important to meticulously check for irregularities and loose bone particles.

Osteotomies

Introduction

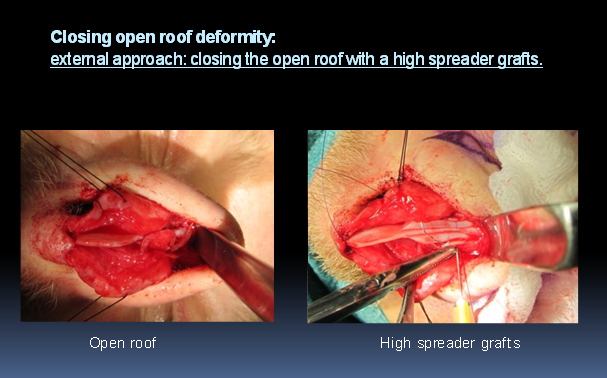

When a patient is analysed for an overprojected nasal dorsum it is important to look at the position and shape of the nasal bones and whether these need any alteration. If there are indications to mobilize the bony pyramid this can be done with osteotomies for in-fracture, out-fracture or realignment of the nasal bones. In this way the bony nasal dorsum can be straightened and the concomitant open roof can be closed, as has been previously outlined, by performing osteotomies (Fig. 6). In some cases, f.e when the bony nasal contour is aesthetically satisfying, closure of the open roof with onlay grafts or a high spreader graft may provide a useful alternative. The high spreader grafts are placed in between the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilage and septum thus separating the outer lining from the inner lining of the nose (Fig. 18 , 19).

Surgical approaches and techniques

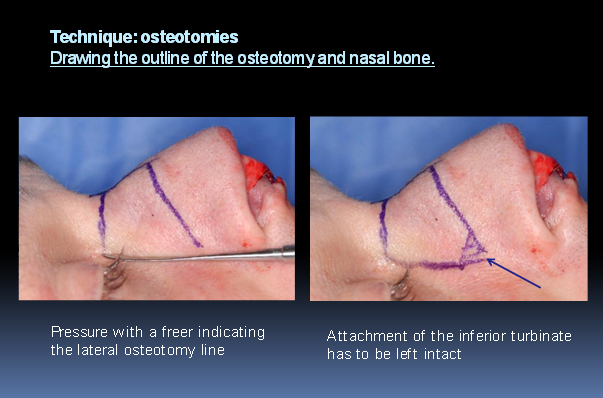

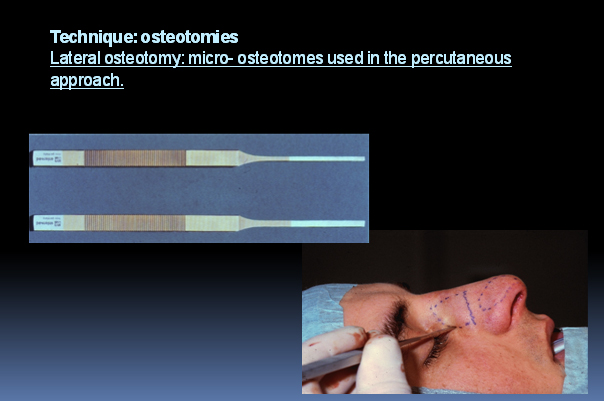

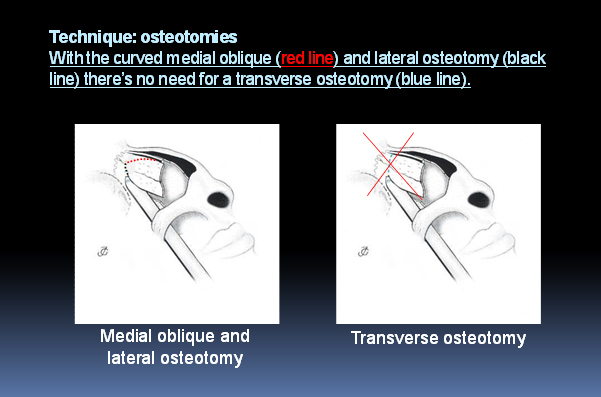

The technique of nasal osteotomies is nowadays more refined resulting in less ecchymosis and oedema. Some contributing factors are the use of local anesthetics with vasocontrictive additives and the use of micro-osteotomes. Other important factors are elimination of the transverse osteotomy through thicker nasal radix bone, by using the medial-oblique osteotomy and leaving the periosteum as much intact as possible. Before starting the osteotomy the outline of the osteotomy and the nasal bones is drawn on the patient. The attachment of the inferior turbinate to the nasal bone is left intact in order not to infract the head of the inferior turbinate. It might be helpful to briefly give some pressure on the skin with a straight instrument (f.e. a freer) to indicate the line to be drawn for the percutaneous lateral osteotomy (Fig. 20)

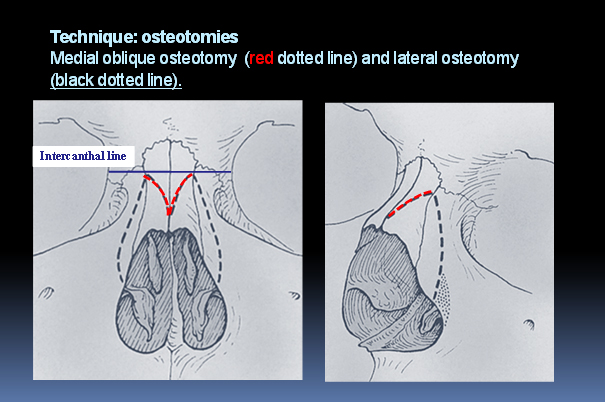

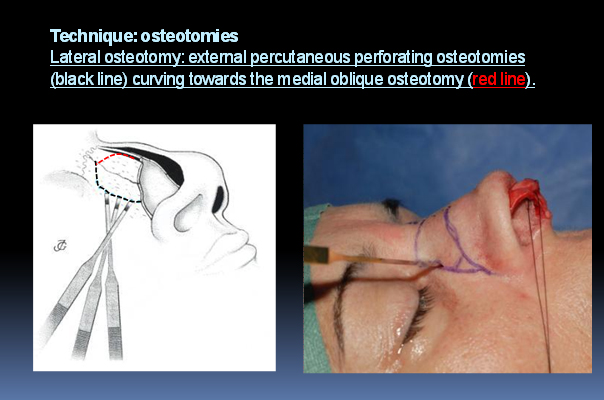

Mobilizing the bony nasal vault requires two osteotomies per side: a medial oblique osteotomy and a slightly curved lateral osteotomy. The lateral osteotomy can be performed percutaneously as well as intranasally. The osteotomies should not run more cephalic than the intercanthal line. Superior from this line the bone of the glabellar region is much thicker and the width of the bony dorsum usually smaller so aesthetically it does not give a better result to go more cranial with the osteotomy (Fig. 21). Besides, there is a risk for a “rocker phenomenon” as is discussed in Complications.

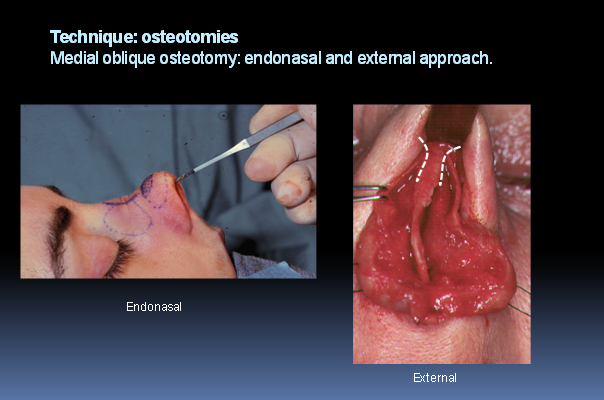

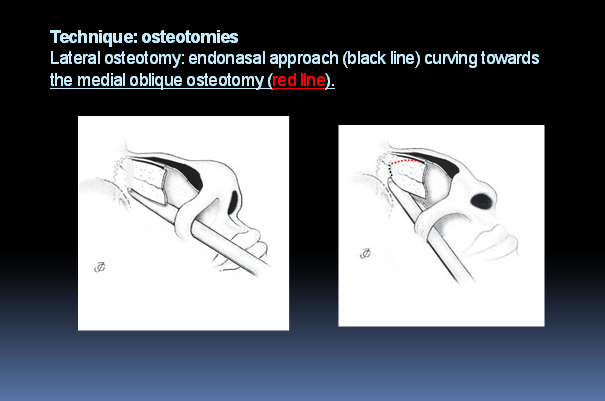

The medial oblique osteotomy is carried out first. The osteotome is put on one side of the nasal bony dorsum just paramedian from the septum in the cutting line with the already separated upper laterals. After the onset it fades already in an oblique way towards lateral. Care is taken not to damage the mucoperichondrium on one side and the SSTE on the other side. When using the endonasal approach one uses the space provided by the already made dorsal tunnel. In the external approach the medial oblique osteotomy can be performed under direct vision (Fig. 22).

(Adapted from Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

(Adapted from Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

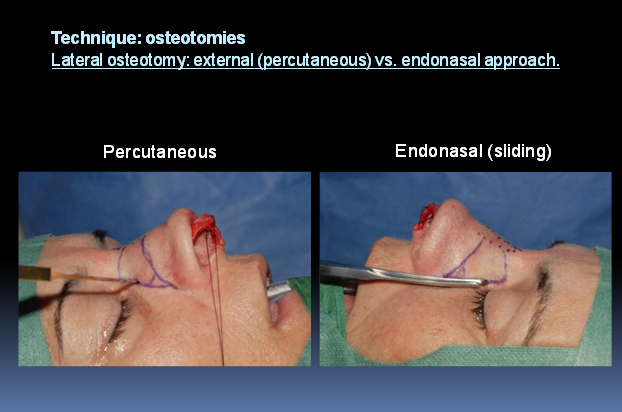

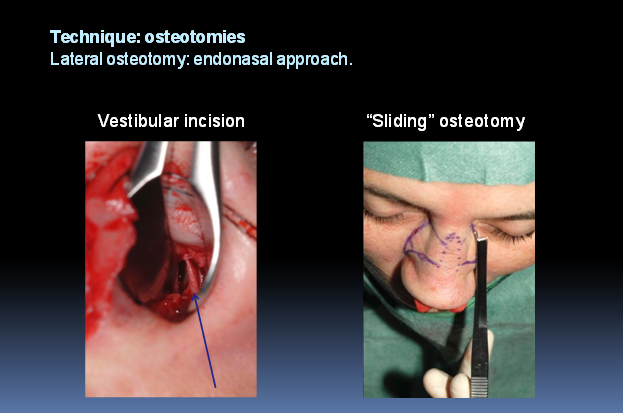

The lateral osteotomy is carried out endonasally or percutaneously (Fig. 23). In the endonasal way is started with infiltration of some local anaesthestics and a vestibular incision at the lateral wall of the of the piriform aperture just superior to the attachment of the inferior turbinate (Fig.24). An osteotome, designed in such a way to protect the nasal mucosa, is introduced and moved in a sliding way from low lateral to high medial to the meeting point with the medial oblique osteotomy just below the intercanthal line (Fig,25).

(Adapted from Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

If the lateral osteotomy is performed percutaneously a stab incision is made in the middle of the line drawn for the lateral osteotomy. The periosteum is pushed aside with a sharp 2 mm micro-osteotome together with the vessels alongside the dorsum (Fig 26, 27). In this way the periosteum is kept intact as much as possible and serves as an internal splint for the fractured bone. With a 3 mm micro-osteotome small perforating osteotomies are made along the planned lateral osteotomy line. Caudally the attachment of the inferior turbinate is left intact and cephalically the perforating osteotomy meets with the medial oblique (Fig 28). By combining these two osteotomies there is no further need for a traditional transverse osteotomy (Fig. 29).

(Adapted from Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

(Adapted from Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

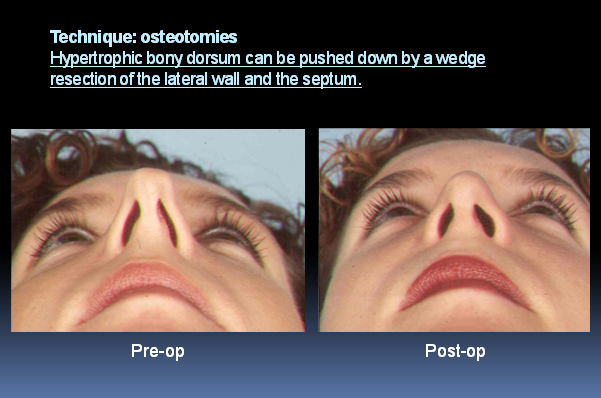

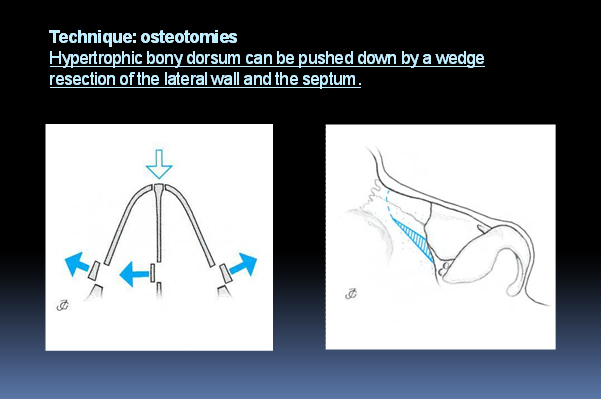

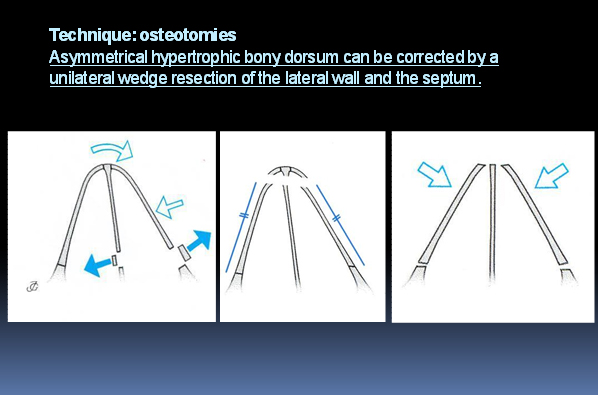

When the bony dorsum is hypertrophic, for instance in case of a “tension nose”, there might http://glbtpridestore.com/online/ be a good indication to lower the complete nasal vault (Fig. 30). This is done by a wedge resection of the lateral bony walls and the septum (Fig. 31). In asymmetric cases it can be useful to perform the wedge resection only on the side that is too high to get a symmetrical post-op result (Fig.32)

(From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

(From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

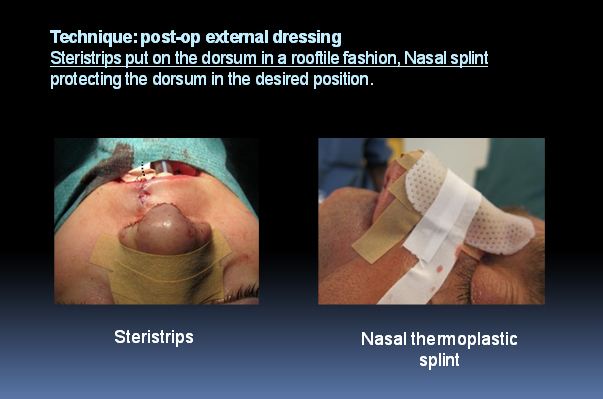

After all the osteotomies are completed the nasal bones are infractured by applying digital pressure. The mobile nasal bones are realigned in the desired position and the open roof deformity is closed. Once the rest of the rhinoplasty is completed the exact position of the nasal skeleton is checked again and fixed in the desired position with a nasal packing on the inside and a nasal splint on the outside. On the outside steristrips are put on the skin from the dorsum to the tip in a rooftile fashion. Sutures for closure of the percutaneous access are not needed. A thermoplastic splint is applied over the nose in such a way that the nasal skeleton is fixed in the desired position between the splint and the nasal packing, giving light pressure from the inside (Fig 33). The packing, gauzes and splint are removed after 3-5 days after which a new splint is applied. After two weeks the patient removes the splint and is seen back in the office at six weeks, six months and one year.

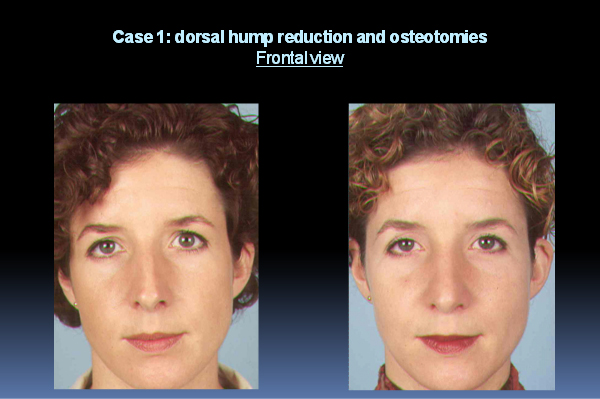

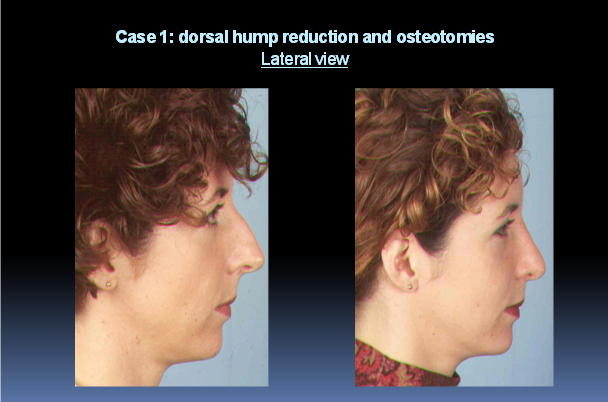

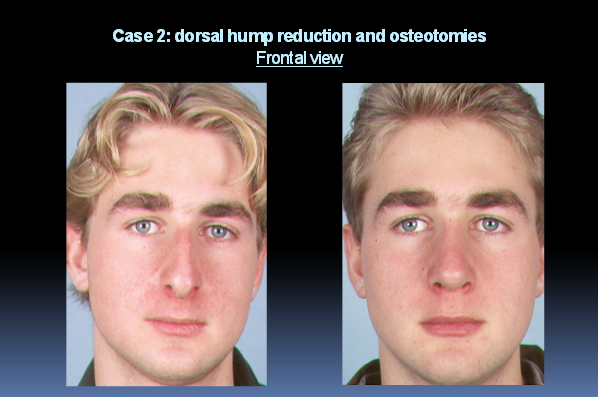

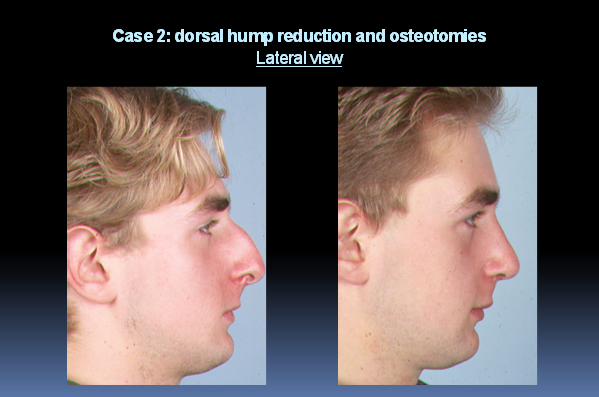

Some pre-and post-op results of a dorsal hump reduction with osteotomies are shown in the following figures (Fig. 34, Fig. 35, Fig. 36, Fig. 37).

Endonasal versus external approach

In theory, each and every procedure can be performed through either an endonasal or an external approach. But, the less experienced a surgeon is, and/or the more caudal the pathology is situated , i.e. cartilaginous dorsum or tip (lower two thirds), the more there is an indication for an external approach. In fact, this means that the beginning rhinoplastic surgeon will prefer an external approach for better view and control.

Manipulation of transplants, mucosa and cartilage is easier in an external approach because the surgeon can work bimanually which will facilitate correction of severe nasal tip deformities. Spreader grafts can be fixated exactly when using the external approach (10,11). Pieces of nasal bone or cartilaginous vault can be removed in a more controlled way and wedges of bone can be chiselled or drilled with a burr.

Disadvantages of the external approach, including supratip edema and unacceptable transcolumellar scars, can largely be avoided by meticulous dissection in surgical planes and precise suturing.

The endonasal approach allows exposure of the nasal dorsum while leaving the nasal tip undisturbed. However, manipulation is more difficult, as binocular vision and bimanual procedures are difficult to establish. Furthermore, due to the limited exposure, there is a substantial traction on the collumellar and dorsal skin.

Each surgeon must weigh the pro’s and con’s of external and endonasal approach preoperatively for each individual case.

Complications

Complications after dorsal hump reduction.

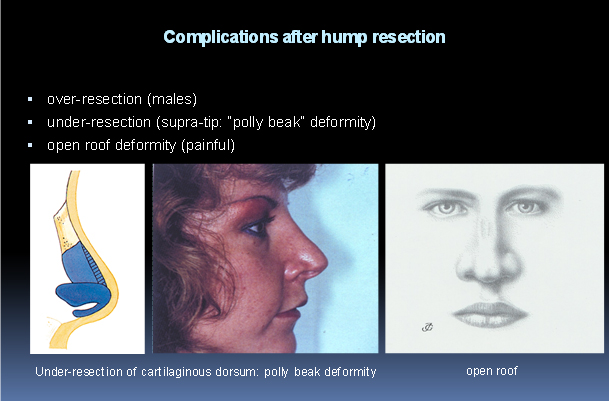

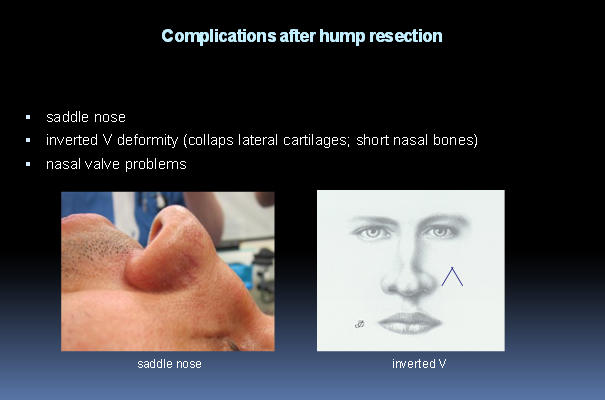

It is wise to discuss the most likely and important complications with the patient. The following complications after dorsal hump reduction can occur: over- and undercorrection, polly beak deformity, open roof, saddle nose, inverted V deformity and nasal valve problems.

One of the most common sequelae of surgery of the overprojected nasal dorsum is over- and undercorrection. When the nasal dorsum is overcorrected, the previously removed material can (partially) be reinserted during the operation (12), otherwise an autogenous septal cartilage graft can be used. Especially in males the overcorrected dorsum is aesthetically disturbing. An undercorrected nasal dorsum should be recognized during surgery (just like an overcorrected dorsum should not be missed during surgery), so that additional bone / cartilage can be removed as a primary procedure. Too little resection of the cartilaginous part of the hump, or relative overresection of the bony part, might lead to a “polly beak deformity”. This is a combination of a lowered nasal dorsum,a relatively high septal angle and loss of tip support after the rhinoplasty which results in a tip deprojection.

An open roof may be unaesthetic but also causes pain because of contact of the mucosa with the overlying skin. In most of these cases medial oblique and lateral osteotomies will be necessary (Fig.38)

(From Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission. From Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

(Adapted from Huizing, E.H., de Groot, J.A.M. Functional Reconstructive Nasal Surgery. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2003, with permission.)

The support of the cartilaginous dorsum might be lost when a complete septal cartilage posterior chondrotomy is done in continuation with the dorsal end of the septum, An L-shaped strut that is fixated to the anterior nasal spine and the nasal bones + upper laterals, is then needed to restore the dorsum. Even in a simple septoplasty the septal cartilage can rotate backwards causing a minimal postoperative depression in the supratip, or a more serious saddle nose (13).

When the upper laterals are sharply divided from the septum as described in the section Surgical Approaches and Technique of the dorsal hump reduction, and not reallocated by suturing to the cranial end of the septal cartilage, they end up in a lower level leading to an inverted V deformity. This can also give a “pinched appearance” to the cartilaginous dorsum and cause functional problems of the nasal valve. Spreader grafts can be used to restore this and lateralize the upper lateral cartilages and reposition the lateral nasal wall along the dorsal margin of the nasal septum (10, 11)(Fig.39).

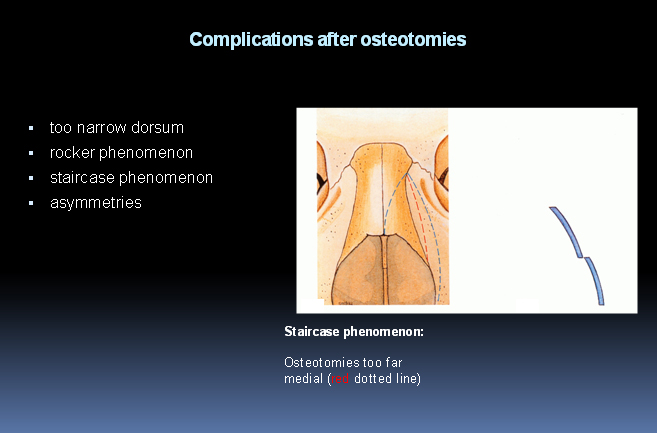

Complications after osteotomies

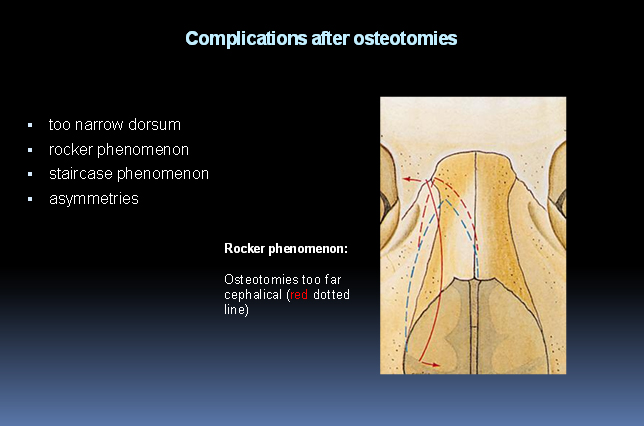

The most common complications after performing osteotomies are: a dorsum that’s too narrow, the “rocker phenomenon”, the staircase phenomenon and asymmetries.

When the nasal bones are infractured to close the open roof deformity one should be aware of too much infraction leading to a dorsum that’s too narrow. This can be prohibited by careful evaluation of the dorsum before closing and if needed pushing the lateral bony walls a bit outward. Good support with endonasal packing should keep the fractured bone in the desired position.

As already mentioned the osteotomies should not run too far cephalically beyond the intercanthal line (Fig.21) , to avoid a rocker phenomenon (5). In this complication the nasal bone is pivoting and the superior aspect of the osteotomized nasal bone may project or “rock” laterally when infracting the distal or caudal ends of the bones (Fig. 40).

If the lateral osteotomy is carried out too far medially the so called staircase phenomenon may arise. Especially in thin skinned patients this might lead to a dissatisfactory result( Fig. 41).

Finally one can end up with an asymmetrical bony dorsum due to a pre-existing asymmetry that was not properly corrected or an osteotomy that was carried out in an asymmetrical way (Fig. 32).

However, when proper techniques are used and as experience is gaining, complications as described above can usually be avoided. Finally, this should lead to a fine predictive result according to the wish of the patient.

(Adapted from Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

(Adapted from Nolst Trenité G.J. Anatomy. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11, with permission.)

Finally the surgical approaches and techniques of a dorsal hump reduction and osteotomies, as described in this chapter, can be seen in the following movie of the correction of the overprojected nasal dorsum (Movie 3).

References

- Tardy ME. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose. New York, Raven Press 1990.

- Nolst Trenité G.J. Aesthetics. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 2.

- Tardy ME, Kron TK, Younger R, et al. The cartilaginous pollybeak: etiology, prevention and treatment. Facial Plast Surg 1989; 6: 2.

- Becker DG, Toriumi DM, Gross CW, Tardy ME Jr. Powered instrumentation for dorsal reduction. Facial Plast Surg. 1997 Oct; 13(4): 291-7.

- Nolst Trenité G.J. Surgery of the osseocartilaginous vault. In: Nolst Trenité G.J., Ed, Rhinoplasty. Kugler Publications The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Chapter 11.

- Harshbarger RJ, Sullivan PK. The optimal medial osteotomy: a study of nasal bone thickness and fracture patterns. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 108(7): 2114-2119.

- Goldfarb M, Gallups JM, Gerwin JM. Perforating osteotomies in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery 1993; 119 (6): 624-627.

- Bull TR. Percutaneous osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001 May; 107(6): 1624-5.

- Murakami CS, Larrabee WF. Comparison of osteotomy techniques in the treatment of nasal fractures. Facial Plast Surg 1992; 8: 209-219.

- Toriumi DM. Management of the middle nasal vault in rhinoplasty. Operative Techniques in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1995; vol 2 (1); 16-30.

- Vuyk HD. Cartilage spreader grafting for lateral augmentation for the middle third of the nose. Face 1993; 3: 159-170.

- Skoog T. A method of hump reduction in rhinoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol 1966; 83: 283.

- Vuyk HD, Langenhuijsen KJ. Aesthetic sequelae of septoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol 1997; 22(3): 226-232